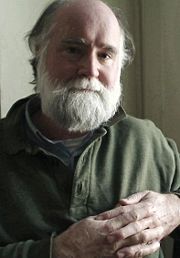

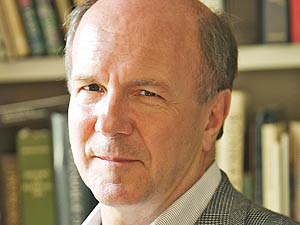

On Thursday night, a crowd congregated into a subterranean hall of the New York Public Library to listen to Simon Winchester interview Nicholson Baker. Mr. Baker wore a green vest and a low-key suit. Mr. Winchester was dressed in a gaudy blue pinstriped suit and a yellow shirt, with a dark red handkerchief drifting out of his outer pocket like a haphazard eleventh-hour accessory.

Baker was soft-spoken, effusive with his hands, and sometimes quietly gushed, particularly when talking about the “lush, colorful” nature of the New York World, one of the early 20th century newspapers that had been in his prodigious collection. Winchester was often sharp and crisp with his questioning, exuding the aura of a fussy countertenor waiting for a cadre choristers to marvel upon his ostensible magnificence, but he was good enough to point out that it was “Nick’s night.” At one point, Winchester poured water only into his glass. Baker, by contrast, filled both his own glass and Winchester’s. Winchester kept his gaze upon Baker throughout the conversation, rarely glancing to the audience. Baker, by contrast, regularly opened himself to the audience when expressing himself.

Baker was soft-spoken, effusive with his hands, and sometimes quietly gushed, particularly when talking about the “lush, colorful” nature of the New York World, one of the early 20th century newspapers that had been in his prodigious collection. Winchester was often sharp and crisp with his questioning, exuding the aura of a fussy countertenor waiting for a cadre choristers to marvel upon his ostensible magnificence, but he was good enough to point out that it was “Nick’s night.” At one point, Winchester poured water only into his glass. Baker, by contrast, filled both his own glass and Winchester’s. Winchester kept his gaze upon Baker throughout the conversation, rarely glancing to the audience. Baker, by contrast, regularly opened himself to the audience when expressing himself.

Shortly after sitting in his seat, Winchester announced to the crowd, “This is not going to be a lovefest.” But despite this pledge of pugilism, Winchester played it relatively safe. He had snide comments pertaining to Adam Kirsch’s review. Contra Kirsch, he pointed out that “stupid, but scary” seemed an appropriate line to discuss war.

Alluding to Checkpoint, Baker observed that his purpose in writing that novel was to ask a simple question: “If you think that your single action can solve the problem, is there a way that someone can talk you out of the problem?” But Baker pointed to Emily Dickinson’s maxim about telling all the truth but telling it slant. Fiction could only go so far. And thus, Human Smoke emerged from these meditations.

Baker pointed out that for every book he has written, he would generally get one third of the way into it before “something goes wrong.” Then, he sets it aside. But he had been working on a book-length history of the Library of Congress, dwelling in particular upon Archibald MacLeish, who was the Librarian of Congress in 1939. MacLeish would go onto become a key propaganda figure during the war. And thus Baker found himself immersed in “an interpretive problem.” He had to understand World War II. So he put aside this project and Human Smoke began to take shape.

In discussing the difference between his fiction and nonfiction, Baker noted, “Fear plays a large part in all this. You want to avoid exposing himself.” It was with this attitude that he tackled the more elaborate project of Human Smoke, of which he pointed out that he couldn’t do justice to the full experience of the war.

Winchester asked Baker about whether it was reasonable to rely almost exclusively on newspapers — the so-called first draft of history — for his book at the expense of historians who came later. Baker pointed out that the reporter who wrote about a major event he experienced “had the balance of things in his mind that brings you to the moment.” He cited the exploding soup cans during the bombing of Coventry — a detail that seemed particularly apposite to his framing of history. He pointed out that newspapers would reprint the entire text of a radio speech and noted that, within the letters to the editor section, one could find a great array of voices.

In dwelling upon Human Smoke‘s cast of characters, Baker expressed great curiosity about Herbert Hoover and pointed out that Victor Klemperer was “an interesting man, a sad man.” But he pointed out that just because he put a quote into the book, this did not mean that he necessarily believed in it. Of Gandhi, he observed, “Sometimes there’s a coldness that’s very disturbing.”

Baker appeared deeply troubled by World War II priorities. He said, “It was easier to fight a war against Germans than it was to allow Jewish refugees.” But he pointed out that he was not qualified. On the question of whether America knew about the Pearl Harbor invasion in advance, Baker opted to “defer to the experts.” Later in the evening, Baker said, “Who were the people who came out of the war with greatness and nobility? The Jews.” And there was an uncomfortable silence from the audience, who began to grow a bit restless.

When I interviewed Mr. Winchester in late 2006, he insisted to me that he was a historian, not a journalist, and expressed umbrage at my notion that he was “covering” the 1906 earthquake, pointing out that historians look back on events with “perspective.” This perspective, however, was not particularly evident last night.

When I interviewed Mr. Winchester in late 2006, he insisted to me that he was a historian, not a journalist, and expressed umbrage at my notion that he was “covering” the 1906 earthquake, pointing out that historians look back on events with “perspective.” This perspective, however, was not particularly evident last night.

Four of his questions pilfered very specific points that were presented during the Human Smoke roundtable discussion — all, of course, without reference. Not only did Winchester read aloud the exact same section from Checkpoint that was referenced on these pages, but he also brought up Jeanette Rankin, the controversy involving the Treaty of Versailles (raised by Colleen Mondor), and the efforts by Cardinal Clemens von Galen to suspend the T-4 program. I wondered if Winchester had spent that afternoon Googling to prepare for a book that had slipped his mind since he blurbed it many months ago.

There was a telling indicator of this propensity during the post-discussion Q&A. Asked about Human Smoke, Mr. Winchester pointed out that he had problems with Baker’s book, but that he would defend his right to write it. The delightful and quick-thinking Paul Holdengräber pointed out that Winchester’s line had originated from Voltaire.

Despite these quibbles, I actually liked Winchester. He was dry and mostly unsmiling, save through a few belabored grimaces that seemed more directed at the CSPAN cameras dutifully videotaping this conversation for Book TV than the audience who had shelled out $15 a head to see this. But he was quite entertaining as a Jeremy Paxman-style interviewer. At one point, he asked Baker point blank about the apparently unquestionable natural impulses that cause people and creatures to kill, citing a gorilla video that had been emailed to him, and some incident involving chickens on his cozy farm in Connecticut as evidence of these apparent impulses. He even managed to find a way to name drop Tom Brokaw — “who is a friend and who I like.” Winchester was an enjoyable blowhard, more Phineas Barnum than Phineas Finn. And juxtaposing his blustery presence with the more empathic Baker worked quite well.

Despite revealing himself later to be a dedicated Malthusian (and this charge seemed more a piece of contrarian theater than bona-fide ideology), Mr. Winchester partially acquitted himself when he bailed Baker out as he was responding to a question from the audience about whether America should now begin negotiating with Islamic fundamentalists. As Baker fumbled for an answer, Winchester quickly pointed out that the Northern Ireland crisis was resolved by talking the issue out through back doors.

As the crowd dissembled, Winchester ran up and down the signing line, balancing books like a juggler signed on for a circus at the last minute. I kept wondering whether he was carrying out some intriguing one-man dramatization of a Tom and Jerry cartoon, but this was not the case. He asked a few folks in the queue if anyone else wanted him to sign his book so that he could go home.

Baker appeared a bit worn out by all the publicity he’s been doing for Human Smoke. But despite his energies waning near the end, he maintained a great humility and offered some lively remarks for a book that is likely to keep fanning the flames of controversy for quite some time.

“Of Gandhi, he observed, ‘Sometimes there’s a coldness that’s very disturbing.'”

Quite an understatement. Gandhi, as potrayed by Ben Kingsley, was a saint. The actual historical figure was, among other things, a young officer in the Boers’ army who *supported* Apartheid (as long as Hindus and “kaffirs” were granted separate status; he didn’t mind being second to whites, but he abhorred the idea of being on a level with blacks).

And then there’s the story of Gandhi’s late wife and “Western medicine”… (Google it for a shock)

For a fascinating take on Churchill and the ill-conceived Trety of Versailles, DO have a look at my great new book — “A Shattered Peace: Veresailles 1919 and the Price We Pay Today” [www.ashatteredpeace.com] just published by Wiley and available at Amazon.com and most book stores.

All the best,

David A. Andelman

david@ashatteredpeace.com

Poor Ed. How could anyone ever have an idea if they weren’t able to pilfer from you. It’s so unfair that you never get any credit.