No matter what kind of liberal or centrist you are, there’s a good chance you’re likely to look to recalcitrant Republicans blocking Obama’s appointment of a Supreme Court Justice or a redfaced fount of colossal stupidity and cartoonish arrogance who is currently running for President as prominent harbingers of our national ills. But in his new book, Listen, Liberal, Thomas Frank, co-founder of The Baffler and author of What’s the Matter With Kansas?, has boldly pinpointed the blame for our growing woes at a Democratic Party that has increasingly turned its back on the working class, cleaves to austere notions of meritocracy, is more likely to serve Wall Street than Main Street (despite campaign rhetoric from years back), and continues to adopt policies popularized under the Clinton Administration that have drastically altered the way seemingly liberal politicians serve the people.

I caught up with Frank as he was racing around the country on a book tour. He was gracious enough to respond to my whirlwind of questions — for his book is very much an argument that begets argument — while adroitly pushing his way through the publicity cyclone. Our lengthy conversation touched on the professional class, progressive Democrats who don’t fit within Frank’s theory, the degree to which one should hold a grudge against a politician, and the kind of bold experimentation that may be necessary to reverse income inequality.

EDWARD CHAMPION: Your book opens with an epigraph from David Halberstam’s excellent book, The Best and the Brightest, suggesting that Obama’s capitulation to corporate interests can be likened to some natural trajectory originating from Roosevelt’s Brain Trust to the many technocrats populating John F. Kennedy’s Cabinet who couldn’t handle Vietnam to the current “best and the brightest” Cabinet enforcing a “meritocratic” economy that has left many working-class people in the cold.

EDWARD CHAMPION: Your book opens with an epigraph from David Halberstam’s excellent book, The Best and the Brightest, suggesting that Obama’s capitulation to corporate interests can be likened to some natural trajectory originating from Roosevelt’s Brain Trust to the many technocrats populating John F. Kennedy’s Cabinet who couldn’t handle Vietnam to the current “best and the brightest” Cabinet enforcing a “meritocratic” economy that has left many working-class people in the cold.

You point to Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter calling Russia “unprofessional” when Putin launched airstrikes against Syria in the fall of 2015, as if bombing the bejesus out of another nation was akin to some middle manager throwing a tantrum over the room temperature during a pivotal board meeting.

I’m fascinated by this idea of any remotely dissenting comment being considered “unprofessional.” It seems a close cousin to the outrage culture that has popped up on social media, whereby any group outraged over an “inappropriate” remark proceeds to demand the immediate firing of those who uttered the sentiment. Both developments stifle necessary discourse that is needed to argue out a difficult subject. But I’m wondering how this relates to income inequality. Perhaps many Americans, from Obama on down, have become indoctrinated in a kind of voluntary censure of any remotely disagreeable opinion. And it cuts both ways. Obama did suggest in September that students were too “coddled” for complaining about offensive viewpoints. In all fairness, is this something that we can entirely level at corporate America? I doubt very highly that any brightly painted break room with pinball machines and Guitar Hero in the corner is going to transform workers into Babbitt-like conformists. So where are Americans learning these cues? What accounts for young voters rejecting the Faustian bargain with their support for Bernie Sanders (curiously unmentioned in your book) or, for that matter, mainstream Democrats who often vote against their own interests by endorsing an endless wave of centrist candidates?

THOMAS FRANK: What makes professionals interesting to me is that they are a privileged social class. They are not the billionaire Koch Brothers, but their top ranks include some of the richest people in the nation. Depending on how you define them, certain kinds of investment banking personnel are professionals, as are Silicon Valley CEOs, and most corporate managers, and so on. My goal in Listen, Liberal is to understand what happens when our left party is dominated by this cohort and dedicated to advancing their interests. The answer is: Income inequality grows and grows.

Basically, professionals are inequality on the hoof. They are inequality walking and breathing and singing little songs to itself about how noble and right it is that the tasteful and deserving people are on top and the boorish stupid ones are on the bottom. And then taking a break to smack their lips over a particularly piquant IPA or a delicately iced artisanal cupcake.

Basically, professionals are inequality on the hoof. They are inequality walking and breathing and singing little songs to itself about how noble and right it is that the tasteful and deserving people are on top and the boorish stupid ones are on the bottom. And then taking a break to smack their lips over a particularly piquant IPA or a delicately iced artisanal cupcake.

That professionals do these things —- that they sing their own triumph -— in a very nice and polite language really shouldn’t surprise you. The Victorians were the same way. The only thing that’s new is that this slice of our upper class has persuaded itself that their politeness is some kind of left-wing political virtue, that it somehow excuses or inoculates their class privilege, and that the bad manners of the lower orders disqualifies any grievances they might have against the system.

Bernie Sanders isn’t mentioned in Listen, Liberal because it’s a book about Democrats and he didn’t identify as a Democrat until very recently, which (by the way) seems to cause no end of annoyance for Democratic party leaders. I was fully aware of his existence, however, and in 2014 I conducted a long interview with him for Salon —- asking his opinion about Democrats, even.

The young voting for Sanders makes perfect sense to me. They are the new proletariat, saddled with crazy student debt and facing a world where the old middle-class dream is suddenly impossible. They did exactly what they were told to do —- go to college! study hard! —- and look at what happened. Look at what a shitty trick the adult world pulled on them. As soon as they were old enough to sign those student loan papers, we put them in debt.

CHAMPION: Your book spends a great deal of time quibbling with the way in which “the best people” are selected for prominent positions and for more lucrative jobs. But I don’t know if professionals can be entirely blamed for the vagaries that you ascribe to them. They may not be suffering like those who were victimized by lenders during the subprime crisis, but they too are motivated by the need to keep food on the table and must play the game if they hope to survive. If the professionals are being nice and polite, tweaking their LinkedIn profiles and marketing themselves at networking functions as “the best,” aren’t they merely succumbing to the rules and folkways of a ruthless capitalist system that no longer welcomes outliers or innovators? To what extent are professionals responsible for this apparent synthesis (to use a “professional” buzz word) between playing it safe and growing income inequality? When did this impulse start? Would you go out on a limb and call these professionals “willing executioners” (a la Goldhagen) in an altogether different nightmare?

FRANK: This is the biggest question of all, isn’t it, and it needs to be asked because I have sketched out a picture of a country in which invisible and even unmentionable forces like class interest seem to pull people this way and that. It is particularly noticeable because the people I’m describing are the ones we always think of not as being part of a “class” but merely as being “the best”: The highly educated people at the top of our system of status and respect.

I think they do have free will and agency, or else I wouldn’t write books like this one —- which is addressed to the very class I’m criticizing, with a big old index finger pointing at them from the cover of the book.

So I think they are culpable to some degree. They should know better. These are highly educated people we’re talking about and they should understand that much of their worldview is based not on fact but on superstition and prejudice —- their unquestioning attitude toward trade deals, for instance, or their knee-jerk contempt for working-class people. You mention their fixation on creativity and innovation, and it has always intrigued me that the literature of creativity and innovation is complete rubbish and yet they eat it up anyway, tuning in to the TED talks and going about their utterly un-innovative business.

So I think they are culpable to some degree. They should know better. These are highly educated people we’re talking about and they should understand that much of their worldview is based not on fact but on superstition and prejudice —- their unquestioning attitude toward trade deals, for instance, or their knee-jerk contempt for working-class people. You mention their fixation on creativity and innovation, and it has always intrigued me that the literature of creativity and innovation is complete rubbish and yet they eat it up anyway, tuning in to the TED talks and going about their utterly un-innovative business.

The story has some complications, too. We have a powerful political party given wholeheartedly to the interests of professionals, but it seems not to notice that certain professions are crumbling (journalism, the humanities) and others are in danger of being corrupted altogether (accountancy, medicine, real-estate appraising). The professionals who have seen their livelihoods thus ruined are angry and even sometimes come to identify with blue-collar workers who have seen their cities destroyed by the Democrats’ great god “globalization.” But the party of the professionals doesn’t listen to these unfortunate members of its own precious cohort.

The ones out front keep playing the game, as you put it, weirdly unconcerned while the devil takes the hindmost. The devil will get to them too, eventually, but in the meantime the winners do not show any sign of awareness. That blindness fascinates me.

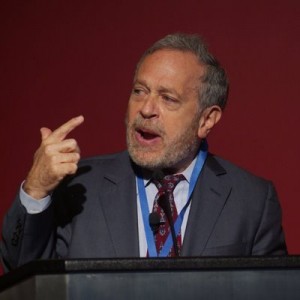

CHAMPION: But the Democratic Party is also the party of Elizabeth Warren, Barbara Lee, John Conyers, Robert Reich, and Donna Edwards, among other progressives. For all the justifiable criticisms leveled against Democrats for hewing too closely to mainstream neoliberalism — or, for that matter, the recent viral videos of Hillary Clinton refusing to address Black Lives Matter’s Ashley Wlliams on mass incarceration or angrily responding to Greenpeace’s Eva Resnick-Day — we are nevertheless dealing with a political climate in which “socialism” is no longer a dirty word. You criticize Reich’s The Work of Nations for endorsing the “symbolic analysts” even as he criticized income inequality and even as you point to his ongoing work against economic injustice. But is this really on the level of Deval Patrick joining the board of leading subprime lender Ameriquest in 2004 after fighting on behalf of the marginalized and the impoverished? Effective political reform is often about compromise. Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson have argued that standing doggedly for one’s principles and refusing to compromise is an endorsement for the status quo. Is there an acceptable level of compromise that can reconcile this disparity between an indignant working class that feels left out of the process and what you identify as a lack of awareness from the “party of professionals”?

CHAMPION: But the Democratic Party is also the party of Elizabeth Warren, Barbara Lee, John Conyers, Robert Reich, and Donna Edwards, among other progressives. For all the justifiable criticisms leveled against Democrats for hewing too closely to mainstream neoliberalism — or, for that matter, the recent viral videos of Hillary Clinton refusing to address Black Lives Matter’s Ashley Wlliams on mass incarceration or angrily responding to Greenpeace’s Eva Resnick-Day — we are nevertheless dealing with a political climate in which “socialism” is no longer a dirty word. You criticize Reich’s The Work of Nations for endorsing the “symbolic analysts” even as he criticized income inequality and even as you point to his ongoing work against economic injustice. But is this really on the level of Deval Patrick joining the board of leading subprime lender Ameriquest in 2004 after fighting on behalf of the marginalized and the impoverished? Effective political reform is often about compromise. Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson have argued that standing doggedly for one’s principles and refusing to compromise is an endorsement for the status quo. Is there an acceptable level of compromise that can reconcile this disparity between an indignant working class that feels left out of the process and what you identify as a lack of awareness from the “party of professionals”?

FRANK: I acknowledge of course that there are exceptions to my theory, and that there are lots of good Democrats out there. There may even be good Republicans out there. Robert Reich is one of the good guys today —- one of the best guys, actually -— but The Work of Nations, which he published way back in 1991, really got the problem of inequality wrong. It heaped praise on what he called “symbolic analysts” (one of many terms of endearment Democrats have made up for white-collar professionals) and announced that, in the future, we would all either have to join their ranks or serve them.

You ask if that’s as bad as one of the missteps of Deval Patrick. I truly have no idea how I would make such a judgment. One is an influential book of economic theory, the other is a promising Democratic politician signing up with a notorious subprime lender. They are analogous deeds, in a way, but also in different categories.

You ask if that’s as bad as one of the missteps of Deval Patrick. I truly have no idea how I would make such a judgment. One is an influential book of economic theory, the other is a promising Democratic politician signing up with a notorious subprime lender. They are analogous deeds, in a way, but also in different categories.

Nor do I really know what the acceptable level of compromise is in some abstract way. I will say this, however: The entire history I trace is one of ordinary people’s interests being systematically ignored and overruled by a clique of upper-class liberals who are in love with their own virtue. They have no trouble with compromise in one direction. Leading Democrats are forever trying to strike a deal with the Republicans in Congress on Social Security and the budget —- think of Obama and his pursuit of the “grand bargain,” a phrase which was my working title for the book. But when it comes to people on the left, Democrats usually invite them simply to shut up. These are people they can’t stand. On this, see: The works and achievements of Rahm Emanuel.

CHAMPION: How does splitting hairs over a neoliberal position taken twenty-five years ago by someone who you now acknowledge to be a bona-fide progressive help us to understand how the Democratic Party has changed or what we need to do to combat it? Let’s contend with bigger fish. You heavily criticize Bill Clinton in your book. And I would tend to agree with you. Bill Clinton’s alliance with Dick Morris, his signing of the 1996 Welfare Reform Act, his deregulation of telecom and interstate banking, and his willful repeal of Glass-Steagall all feel very much like the actions of a “bad Democrat” and the kind of narrative that gets swept under the rug in these discussions on how many Democrats aren’t terribly dissimilar from Republicans. I’m sure you’re familiar with the infamous story behind Bill and Hillary Clinton’s first date, which involved the pair crossing a picket line and offering themselves as scabs so they could see a Rothko exhibit at the Yale Art Gallery. This aligns neatly with the problems you’re identifying. But it also suggests that the more pernicious qualities of compromise lie dormant inside any politician who aspires to great power. You also observe that Obama’s three great achievements — the 2009 stimulus package, Dodd-Frank, and the Affordable Care Act — are undermined by Democrats who follow up with a professional-minded consensus. If we’re going to call out the “party of professionals,” don’t we need to consider the full narrative of how the more prominent figureheads have stood against the working class instead of singling out comparatively minor indiscretions from those who are now fighting against income inequality?

FRANK: You’re talking about Robert Reich and The Work of Nations again. My understanding of history is that we are supposed to seek the truth about how the past unfolded regardless of whether historical actors later change their minds or express regret for what they did. Bill Clinton has apologized several times for the 1994 crime bill as well as for many other things; that might make us think more highly of him as a person but it doesn’t undo the crime bill or erase its consequences from history. Similarly, The Work of Nations was an essential document of its time. It was very influential in the early years of the Clinton Administration. Its author was made Secretary of Labor. That Reich has changed his views since then is commendable —- and I think very highly of what he’s doing now -— but his conversion to a different point of view in recent years doesn’t change the political culture of the 1990s.

FRANK: You’re talking about Robert Reich and The Work of Nations again. My understanding of history is that we are supposed to seek the truth about how the past unfolded regardless of whether historical actors later change their minds or express regret for what they did. Bill Clinton has apologized several times for the 1994 crime bill as well as for many other things; that might make us think more highly of him as a person but it doesn’t undo the crime bill or erase its consequences from history. Similarly, The Work of Nations was an essential document of its time. It was very influential in the early years of the Clinton Administration. Its author was made Secretary of Labor. That Reich has changed his views since then is commendable —- and I think very highly of what he’s doing now -— but his conversion to a different point of view in recent years doesn’t change the political culture of the 1990s.

I most definitely think we need to underscore how prominent Democratic figureheads have stood against the working class, and in particular we need to look at their ideas and their legislative deeds. This is why I go into such detail on the legislative history of the Clinton years, focusing especially on the five items his admirers actually celebrated him for: NAFTA, the crime bill, welfare reform, deregulation of banks and telecoms, and the balanced budget. All of these were disasters for working people, either directly or indirectly.

The issue of compromise and consensus is a fascinating one. Democrats have been far more earnest seekers of consensus than Republicans, and I wanted to know why. This is one of the biggest differences between the two parties, and the “party of the professionals” hypothesis explains it perfectly. The politics of professionalism is technocracy, an ideology in which the solution to every problem is known to educated people and the correct experts. When they look at Washington, technocrats know that politics is just a form of entertainment that gets in the way of the right-minded; it blocks the educated people from doing what everyone knows is the right thing; and therefore technocrats always gravitate to the same answer: try to reach a grand bargain with the smart folks on the other side. Thus Obama on the budget, and thus Clinton on Social Security.

CHAMPION: History is certainly about understanding how powerful figures alter their viewpoints and adjust their positions. But if Reich was willing to change, why then is a putatively liberal government so unwilling to adjust its course? You point to how FDR employed experts — such as Harry Hopkins, Marriner Eccles, Henry Wallace, and Harry Truman — who were all outliers in some way, many with a lack of academic credentials that led to bold ideas and off-kilter policies. But Roosevelt’s response to financial paralysis was also famously guided by the mantra “Above all, try something.”

It was certainly “bold, persistent experimentation” that Roosevelt called for in 1932, but some historians have argued that it was both the law of averages and Roosevelt’s centralized authority that allowed for his much needed reform to happen. If we want to repair income inequality, is our only remedy some autocratic figure operating in the FDR/Hamilton mode who is granted supreme authority and willing to employ any tactic to do so? Or are there other remedies that aren’t teetering perilously towards such absolutism? To cite one example of the Beltway dynamics in play here, it remains to be seen whether Republican senators will change their mind on potential Supreme Court Justice Merrick Garland, but the legislative opposition suggests that “bold, persistent experimentation” isn’t going to be allowed anytime soon and that any future Democratic President is fated to be hamstrung by the very technocratic compromise that you’re understandably condemning. On the other hand, “bold, persistent experimentation” — as recently documented by journalist Gabriel Sherman — is precisely what has allowed Trump to sink his talons into the 2016 election as much as he has. Trump is a perfect example of politics as “a form of entertainment that gets in the way of the right-minded” and this didn’t even come from technocratic Democrats. So is there any real hope for repair? Do you feel that there’s any truth to Susan Sarandon’s recent suggestion to Chris Hayes, mired in controversy, that a potential Trump Presidency might inspire more people to take a gamble on a progressive revolution (if that is indeed what is needed here)?

It was certainly “bold, persistent experimentation” that Roosevelt called for in 1932, but some historians have argued that it was both the law of averages and Roosevelt’s centralized authority that allowed for his much needed reform to happen. If we want to repair income inequality, is our only remedy some autocratic figure operating in the FDR/Hamilton mode who is granted supreme authority and willing to employ any tactic to do so? Or are there other remedies that aren’t teetering perilously towards such absolutism? To cite one example of the Beltway dynamics in play here, it remains to be seen whether Republican senators will change their mind on potential Supreme Court Justice Merrick Garland, but the legislative opposition suggests that “bold, persistent experimentation” isn’t going to be allowed anytime soon and that any future Democratic President is fated to be hamstrung by the very technocratic compromise that you’re understandably condemning. On the other hand, “bold, persistent experimentation” — as recently documented by journalist Gabriel Sherman — is precisely what has allowed Trump to sink his talons into the 2016 election as much as he has. Trump is a perfect example of politics as “a form of entertainment that gets in the way of the right-minded” and this didn’t even come from technocratic Democrats. So is there any real hope for repair? Do you feel that there’s any truth to Susan Sarandon’s recent suggestion to Chris Hayes, mired in controversy, that a potential Trump Presidency might inspire more people to take a gamble on a progressive revolution (if that is indeed what is needed here)?

FRANK: As it happens, there was a golden moment for boldness and experimentation in recent years, and it came and went in 2009 after the collapse of Wall Street and its rescue by the Federal government. Many things were possible in that moment that weren’t possible at other times. But that particular crisis went to waste. Obama deliberately steered us back toward the status quo ante, and worked hard to get everything back like it was before. “The Center Held,” to slightly modify the title of Jonathan Alter’s second Obama book.

Regarding Trump: I am a big fan of Franklin Roosevelt, and I don’t think that Trump is comparable in any way. Being willing to go before the cameras and say anything, like Trump, does not really put a politician in the same category as FDR, any more than does being a jazz musician who is a great soloist or a comedian who’s really good at improv.

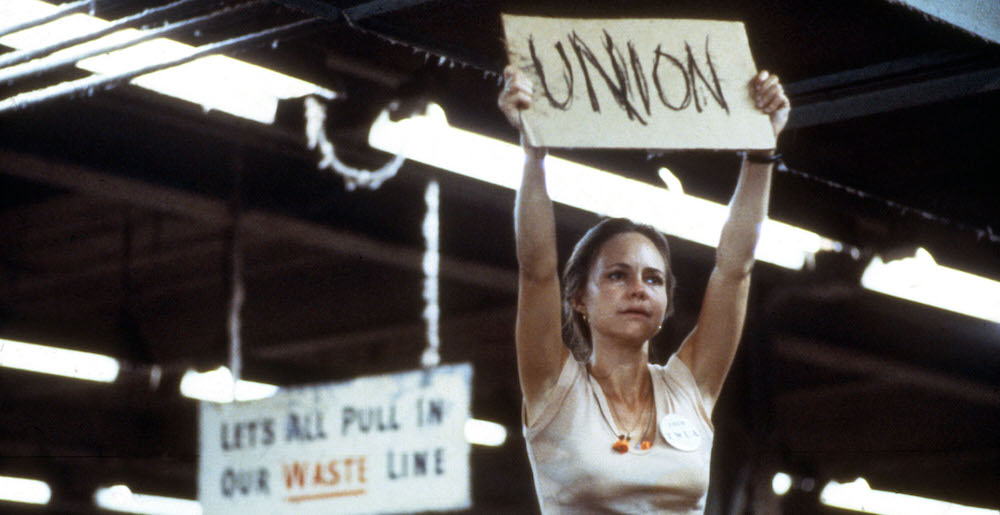

Your concern about the present situation possibly requiring an autocrat or an absolutist is very intriguing, however, and it’s a common fear. But flip the question around a little bit. The way I see it, autocracy is already here —- economic autocracy, I mean -— and democracy is the solution. It is true what you say about Roosevelt wielding power like few other presidents, but the things that really turned this country around involved economic democracy more than they did the heavy hand of the state. I am thinking in particular here of two things that we identify with FDR, antitrust and organized labor. Both of them involved challenging oligarchy by empowering countervailing forces, either competitors or workers.

Let’s talk about unions for a moment. They are profoundly democratic institutions even when they aren’t full democracies themselves (a common problem) because they extend the idea of democratic rights and voice into the workplace. For decades Americans thought of unions as a normal part of civil society, and yet today they are dying, thanks to the one-sided power of corporate management -— and the indifference of their friends in the Democratic Party. What’s awesome about unions is that they would help enormously to reduce inequality, and they would do it without the heavy hand of the state. No need for massive redistribution by Washington: just allow workers to have a voice, let them negotiate a contract with their employer, and they will take care of it automatically. More democracy will solve the problem.

CHAMPION: But is democracy enough to combat economic autocracy? We’re dealing with a strong plutocratic base of mainstream Democratic voters and whatever fallout we’re going to have in this post-Citizens United political landscape. The “fight for $15” battle, arguably labor’s greatest recent development, is part of the conversation only because workers made this happen at the local level. There are also pragmatics to consider. Bernie Sanders gave a recent interview to the New York Daily News Editorial Board that has made the rounds. Aside from the stunning revelation that Sanders is unfamiliar with subway MetroCards (which is understandable), the larger concern was that Sanders appeared unable to pinpoint a precise method for breaking up the banks. At the beginning of the book, you describe a Seattle firefighter asking you if there was any economic savior that would prevent the middle class from sinking into poverty. You write, “I had no good answer for him. Nobody does.” If you’re asking the so-called “symbolic analysts” to jump on board the bus passing through Decatur, they’re going to need an answer. They’re going to need more than a loose theoretical idea of what the Fed can do to rein in JP Morgan Chase and corporate greed. What can you possibly tell them to shake them out of their status quo stupor? Is this a struggle where working and middle class liberals are fated to fight in their respective corners? How might technocrats be persuaded to become more inclusive beyond revisiting the historical record?

CHAMPION: But is democracy enough to combat economic autocracy? We’re dealing with a strong plutocratic base of mainstream Democratic voters and whatever fallout we’re going to have in this post-Citizens United political landscape. The “fight for $15” battle, arguably labor’s greatest recent development, is part of the conversation only because workers made this happen at the local level. There are also pragmatics to consider. Bernie Sanders gave a recent interview to the New York Daily News Editorial Board that has made the rounds. Aside from the stunning revelation that Sanders is unfamiliar with subway MetroCards (which is understandable), the larger concern was that Sanders appeared unable to pinpoint a precise method for breaking up the banks. At the beginning of the book, you describe a Seattle firefighter asking you if there was any economic savior that would prevent the middle class from sinking into poverty. You write, “I had no good answer for him. Nobody does.” If you’re asking the so-called “symbolic analysts” to jump on board the bus passing through Decatur, they’re going to need an answer. They’re going to need more than a loose theoretical idea of what the Fed can do to rein in JP Morgan Chase and corporate greed. What can you possibly tell them to shake them out of their status quo stupor? Is this a struggle where working and middle class liberals are fated to fight in their respective corners? How might technocrats be persuaded to become more inclusive beyond revisiting the historical record?

FRANK: There are all sorts of practical things that can be done to address inequality and halt the deterioration of the middle class; I mentioned two of the biggest in my last answer. Doing something about runaway financialization is also a good idea, even if Bernie Sanders couldn’t name the exact legal method by which he would do it in that one interview. Inequality is not an insoluble problem. What that firefighter was asking, however, was what kind of band-aid will be tossed to working people under our present course and our existing system. Clearly the answer to that is . . . nothing.

Well, maybe something. Maybe, under President Hillary Clinton, there’ll be microloans for all. Good times.

However, to make something real happen will require a major political reversal, a reversal in which politics once again reflects the interests of the country’s working-class majority. This will only happen if such people themselves demand it, and it heartens me to see that we are moving decisively closer to that this election year.

The main thing required of the comfortable liberal class in such a situation is to take a good long look at themselves and their happy world and understand that they aren’t the bearers of virtue and righteousness that the media constantly assures them they are. They need to understand that a good chunk of their political worldview is based on attitudes that are little more than prejudice toward people who didn’t follow the same university-based career path as them.

What they need is a moment of introspection. What they need is to understand that those people in Decatur are their neighbors, their relatives, their fellow Americans, and that’s why I wrote this book.

The shop was owned by a quiet, portly and agreeable man with thinning sandy hair, egg-shaped spectacles working wonders accentuating his two thin horizontal slats into an owl-like visage, and a bristling moustache. He was a friendly guy, fond of chatting with the post-teen, pre-college transfer hired help. He outsourced desperate young plebeians like me for low wages to perform mind-numbing tasks that he wouldn’t dare perform himself: in my case, collating thousands of high school newspapers and bland user documentation put out by fledgling startups.

The shop was owned by a quiet, portly and agreeable man with thinning sandy hair, egg-shaped spectacles working wonders accentuating his two thin horizontal slats into an owl-like visage, and a bristling moustache. He was a friendly guy, fond of chatting with the post-teen, pre-college transfer hired help. He outsourced desperate young plebeians like me for low wages to perform mind-numbing tasks that he wouldn’t dare perform himself: in my case, collating thousands of high school newspapers and bland user documentation put out by fledgling startups.  But one day, Limbaugh eventually revealed his colors. On June 6, 1994, Clinton was in Europe to recognize the 50th anniversary of Normandy. And like any President, he staged the predictable photo ops. Clinton gave a speech. He walked lone along the beach of Normandy, preparing a cairn. Hardly surprising. All politicians are forced to embrace artificiality at some point. It’s only the most gifted politician who can make every moment feel natural.

But one day, Limbaugh eventually revealed his colors. On June 6, 1994, Clinton was in Europe to recognize the 50th anniversary of Normandy. And like any President, he staged the predictable photo ops. Clinton gave a speech. He walked lone along the beach of Normandy, preparing a cairn. Hardly surprising. All politicians are forced to embrace artificiality at some point. It’s only the most gifted politician who can make every moment feel natural.  Which makes the recent Washington Post news that

Which makes the recent Washington Post news that