(This is the twenty-third entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: Why We Can’t Wait.)

In his 1966 essay “The White Man’s Guilt,” James Baldwin — never a man to mince words or to refrain from expressing searing clarity — declared that white Americans were incapable of facing the deep wounds suppurating in the national fabric because of their refusal to acknowledge their complicity in abusive history. Pointing to the repugnant privilege that, even today, hinders many white people from altering their lives, their attitudes, and the baleful bigotry summoned by their nascent advantages, much less their relationships to people of color, Baldwin noted:

For history, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.

Fifty-four years after Baldwin, America now finds itself enmired within its most seminal (and long delayed) civil rights movement in decades, awakened from its somnambulistic malaise through the neck-stomping snap of systemic racism casually and ignobly practiced by crooked cops who are afforded impunity rather than significant consequences. The institution of slavery has been replaced by the indignities of racial profiling, income disparity, wanton brutality, constant belittlement, and a crass cabal of Karens who are more than eager to rat out people of color so that they can scarf down their soy milk lattes and avocado toast, rarely deviating from the hideous cues that a culture — one that prioritizes discrimination first and equality last — rewards with all the perfunctory mechanics of a slot machine jackpot.

Thus, one must approach James McPherson’s mighty and incredibly impressive Civil War volume with mindfulness and assiduity. It is not, as Baldwin says, a book that can merely be read — even though it is something of a miracle that McPherson has packed as much detail and as many considerations as he has within more than 900 pages. McPherson’s volume is an invaluable start for anyone hoping to move beyond mere reading, to significantly considering the palpable legacy of how the hideous shadow of white supremacy and belittlement still plagues us in the present. Why does the Confederate flag still fly? Why do imperialist statues — especially monuments that celebrate a failed and racist breakaway coalition of upstart states rightly starved and humiliated and destroyed by Grant and Sherman — still stand? Battle Cry of Freedom beckons us to pay careful attention to the unjust and bestial influences that erupted before the war and that flickered afterwards. It is thankfully not just a compilation of battle summaries — although it does do much to mark the moments in which the North was on the run and geography and weather and lack of supplies often stood in its way. The book pays welcome scrutiny to the underlying environment that inspired the South to secede and required a newly inaugurated Lincoln to call for 75,000 volunteers a little more than a month after he had been sworn in as President and just after the South Carolina militia had attacked Fort Sumter.

* * *

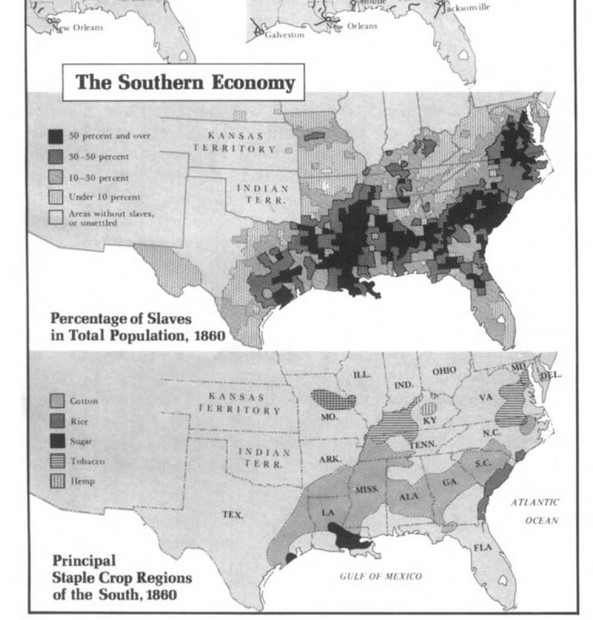

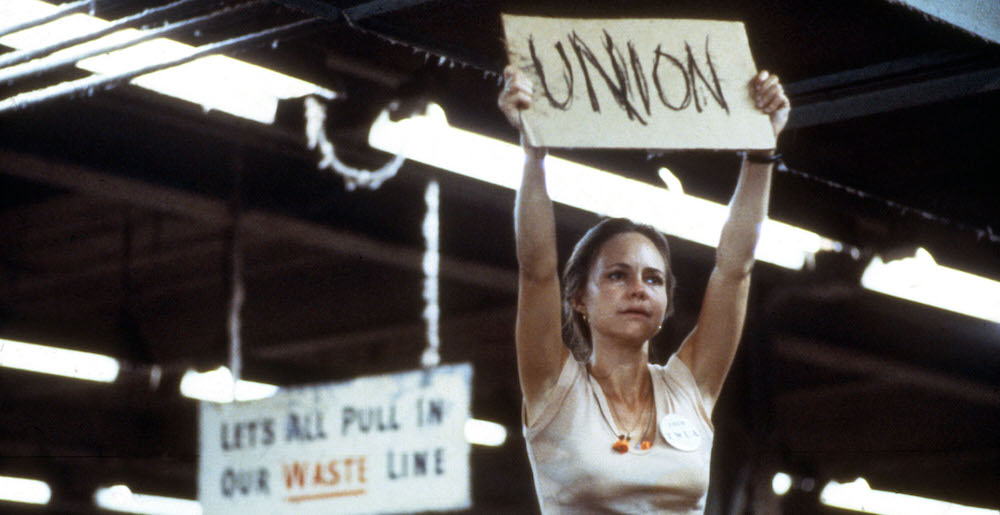

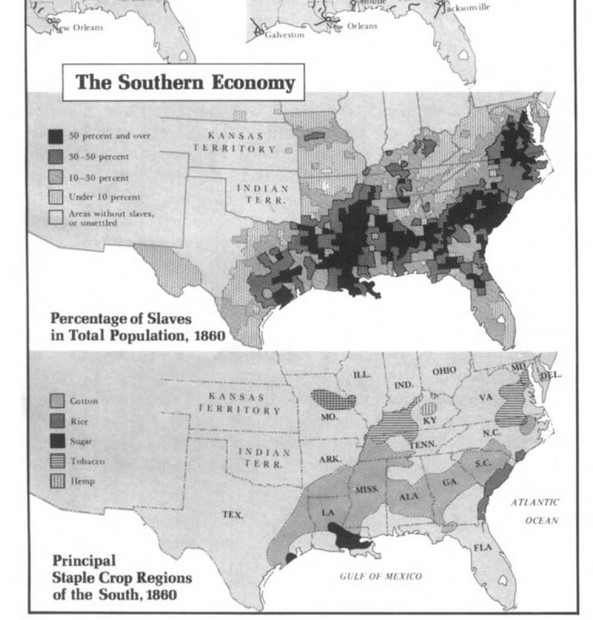

It was technological innovation in the 1840s and the 1850s — the new machines putting out watches and furniture and bolts and damn near anything into the market at a rapid clip previously unseen — that helped sow the seeds of labor unrest. To use the new tools, a worker had to go to a factory rather than operating out of his home. To turn the most profit possible and sustain his venal wealth, the aspiring robber baron had to exploit the worker at subhuman wages. The South was more willing to enslave people. A barbaric racist of that era ranting in a saloon could, much like one of Trump’s acolytes today, point to the dip in the agricultural labor force from 1800 to 1860. In the North, 70% of labor was in agriculture, but this fell to 40%. But in the South, the rate remained steady at 80%. But this, of course, was an artificial win built on the backs of Black lives.

You had increasing territory in the West annexed to the United States and, with this, vivacious crusaders who were feeling bolder about their causes. David Wilmot, a freshman Congressional Representative, saw the Mexican War as an opportunity to lay down a proviso on August 8, 1846. “[N]either slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory” were the words that Wilmot added to an appropriations bill amendment. Like any politician, Wilmot was interested in settling scores. The Wilmot Proviso was as much the result of long pent-up frustration among a cluster of Northern Democrats who cared more about holding onto power than pushing forward abolition. The proviso kept being reintroduced and the Democratic Party of the time — much of it composed of racists from the South — began to splinter.

Northern Democrats shifted their support from the Wilmot Proviso to an idea known as popular sovereignity, which placed the decision on whether to sustain or abolish slavery into the hands of settlers moving into the new territories. But Wilmot’s more universal abolition approach still had the enthusiastic support of northern Whigs. The Whigs, for those who may not recall, were essentially middle-class conservatives living it large. They represented the alternative to Democrats before the Republican Party was created in 1854. The Whigs emerged from the ashes of the Nullification Crisis of 1832 — which you may recall me getting into when I was tackling Herbert Croly a few years ago. Yes, Andrew Jackson was responsible for (a) destroying the national bank, thus creating an economically volatile environment and (b) creating enough fury for Henry Clay and company to form an anti-Jackson opposition party. What’s most interesting here is that opposing Jackson also meant opposing one of his pet causes: slavery. And, mind you, these were pro-business conservatives who wanted to live the good life. This is a bit like day trading bros dolled up in Brooks Brothers suits suddenly announcing that they want universal healthcare. Politics may make strange bedfellows, but sometimes a searing laser directed at an enemy who has jilted you in the boudoir creates an entirely unexpected bloc.

Many of the “liberals” of that era, especially in the South, were very much in favor of keeping slavery going. (This historical fact has regrettably caused many Republicans to chirp “Party of Lincoln!” in an attempt to excuse the more fascistic and racist overtures that these same smug burghers wallow in today.) Much like Black Lives Matter today and the Occupy Wall Street movement nine years ago, a significant plurality of the Whigs, who resented the fact that their slave-owning presidential candidate Zachary Taylor refused to take a position on the Wilmot Proviso, were able to create a broad coalition at the Free Soil convention of 1848. Slavery then became one of the 1848 presidential election’s major issues.

In Battle Cry, McPherson nimbly points to how all of these developments led to a great deal of political unrest that made the Civil War inevitable. Prominent Republican William H. Seward (later Lincoln’s Secretary of State) came out swinging against slavery, claiming that compromise on the issue was impossible. “You cannot roll back the tide of social progress,” he said. The 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act (authored by Stephen Douglas) repealed the Missouri Compromise, which in turn led to “Bleeding Kansas” — a series of armed and violent struggles over the legality of slavery that carried on for the next seven years. (Curiously, McPheron downplays Daniel Webster’s 1850 turncoat “Seventh of March” speech, which signaled Webster’s willingness to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act and forever altered his base and political career.) And while all this was happening, cotton prices in the South were rising and a dying faction of Southern unionists led the Southern states to increasingly consider secession. The maps of 1860 reveal the inescapable problem:

* * *

The Whigs were crumbling. Enter Lincoln, speaking eloquently on a Peroria stage on October 16, 1854, and representing the future of the newly minted Republican Party:

When the white man governs himself that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government — that is despotism. If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that “all men are created equal;” and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.

Enter the Know Nothings, a third party filling a niche left by the eroding Whigs and the increasingly splintered Democratic Party. The Know Nothings were arguably the Proud Boys of their time. They ushered in a wave of nationalism and xenophobia that was thoughtfully considered by the Smithsonian‘s Lorraine Boissoneault. What killed the Know Nothings was their failure to take a stand on slavery. You couldn’t afford to stay silent on the issue when the likes of Dred Scott and John Brown were in the newspapers. The Know Nothings further scattered political difference to the winds, giving Lincoln the opportunity to unite numerous strands under the new Republican Party and win the Presidency during the 1860 election, despite not being on the ballot in ten Southern states.

With Lincoln’s win, seven slave states seceded from the union. And the beginnings of the Confederacy began. Historians have been arguing for years over the precise reasons for this disunion. If you’re a bit of a wonk like me, I highly recommend this 2011 panel in which three historians offer entirely different takeaways. McPherson, to his credit, allows the events to unfold and refrains from too much editorializing. Although throughout the book, McPherson does speak from the perspective of the Union.

* * *

As I noted when I tackled John Keegan’s The Face of Battle, one of my failings as an all-encompassing dilettante resides with military history, which I find about as pleasurable to read as sprawling myself naked, sans hat or suntan lotion, upon some burning metal bed on a Brooklyn rooftop during a hot August afternoon — watching tar congeal over my epidermis until I transform into some ugly onyx crust while various spectators, saddled with boredom and the need to make a quick buck, film me with their phones and later email me demands to pay up in Bitcoin, lest my mindless frolicking be publicly uploaded to the Internet and distributed to every pornographic website from here to Helsinki.

That’s definitely laying it on thicker than you need to hear. But it is essential that you understand just how much military history rankles me.

Anyway, despite my great reluctance to don a tricorne of any sort, McPherson’s descriptions of battles (along with the accompanying illustrations) did somehow jolt me out of my aversion and make me care. Little details — such as P.G.T. Beauregard designing a new Confederate battle flag after troops could not distinguish between the Confederate “stars and bars” banner from the Union flag in the fog of battle — helped to clarify the specific innovations brought about by the Civil War. It also had never occurred to me how much the history of ironclad vessels began with the Civil War, thanks in part to the eccentric marine engineer John Ericsson, who designed the famed USS Monitor, designed as a counterpoint to the formidable Confederate vessel Virginia, which had been created to hit the Union blockade at Ronoake Island. What was especially amazing about Ericsson’s ship was that it was built and launched rapidly — without testing. After two hours of fighting, the Monitor finally breached the Virginia‘s hull with a 175-pound shot, operating with barely functioning engines. For whatever reason, McPherson’s vivid description of this sea battle reminded me of the Mutara Nebula battle at the end of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

But even for all of McPherson’s synthesizing legerdemain, the one serious thing I have to ding him on is his failure to describe the horrors of slavery in any form. Even William L. Shirer in The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich devoted significant passages to depicting what was happening in the Holocaust death camps. Despite my high regard for McPherson’s ability to find just the right events to highlight in the Civil War timeline, and his brilliantly subtle way of depicting the shifting fortunes of the North and the South, can one really accept a volume about the Civil War without a description of slavery? McPherson devotes more time to covering Andersonville’s brutal statistics (prisoner mortality was 29% and so forth) before closing his paragraph with this sentence:

The treatment of prisoners during the Civil War was something that neither side could be proud of.

But what of the treatment of Black people? Why does this not merit so much as a paragraph? McPherson is so good at details — such as emphasizing the fact that Grant’s pleas to have all prisoners exchanged — white and Black — in the cartel actually came a year after negotiations had stopped. He’s good enough to show us how southern historians have perceived events (often questionably). Why then would he shy away from the conditions of slavery?

The other major flaw: Why would McPherson skim over the Battle of Gettysburg in just under twenty pages? This was, after all, the decisive battle of the war. McPherson seems to devote more time, for example, on the Confederate raids in 1862. And while all this is useful to understanding the War, it’s still inexplicable to me.

But these are significant nitpicks for a book that was published in 1988 and that is otherwise a masterpiece. Still, I’m not the only one out here kvetching about this problem. The time has come for a new historian — ideally someone who isn’t a white male — to step up to the challenge and outdo both Ken Burns and James McPherson (and Shelby Foote, who I’ll be getting to when we hit MLNF #15 in perhaps a decade or so) and fully convey the evils and brutality of slavery and why this war both altered American life and exacerbated the problems we are still facing today.

Next Up: Lewis Mumford’s The City in History!