(This is the twenty-sixth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.)

When I last dived into Evelyn Waugh’s exquisite comic fiction for this crazy project nearly six years ago, I wrote a sour essay in which I permitted my hostility towards Waugh’s pugnacious life and his reactionary politics to overshadow my appreciation for his art. Perhaps the way I read fiction has changed or the idea of completely discounting a writer’s achievements with the histrionic tone of an upbraiding Pollyanna who doesn’t possess a scintilla of self-awareness fills me with a dread I usually associate with wincing at a tax bill or standing in a needlessly long line for a pizza slice. Whatever the case, I allowed myself to zero in on Brideshead Revisited‘s weaker elements (namely, the deplorable gay stereotype Anthony Blanche) without possessing the decency to praise that novel’s excellent prose in any way. This was decidedly uncharitable of me. For Waugh was, for all of his faults, a master stylist. That I was also bold enough to rank Wodehouse over Waugh was likewise problematic (although I would still rather read Pip and I have never been able to get into the Sword of Honour trilogy and I still feel that Waugh was more or less finished as an author after The Loved One; incidentally, Waugh himself called Wodehouse “the Master”). At the time, the eminently reasonable Cynthia Haven offered what I now deem to be appropriate pushback, observing that I brought a lot of “post-modern baggage” into my reading. My “take” on that novel’s Catholic dialogue was, I now realize after diving into Waugh again, driven by a cocky yahooism that is perhaps better deployed while knocking back pints in a sports bar and claiming that you’re a big fan of the team everybody else is cheering for. Never mind that the names of the players are only lodged in your memory by the blinding Chryon reminders and the bellowing cries of histrionic announcers that work together to perfect a sense-deadening television experience.

When I last dived into Evelyn Waugh’s exquisite comic fiction for this crazy project nearly six years ago, I wrote a sour essay in which I permitted my hostility towards Waugh’s pugnacious life and his reactionary politics to overshadow my appreciation for his art. Perhaps the way I read fiction has changed or the idea of completely discounting a writer’s achievements with the histrionic tone of an upbraiding Pollyanna who doesn’t possess a scintilla of self-awareness fills me with a dread I usually associate with wincing at a tax bill or standing in a needlessly long line for a pizza slice. Whatever the case, I allowed myself to zero in on Brideshead Revisited‘s weaker elements (namely, the deplorable gay stereotype Anthony Blanche) without possessing the decency to praise that novel’s excellent prose in any way. This was decidedly uncharitable of me. For Waugh was, for all of his faults, a master stylist. That I was also bold enough to rank Wodehouse over Waugh was likewise problematic (although I would still rather read Pip and I have never been able to get into the Sword of Honour trilogy and I still feel that Waugh was more or less finished as an author after The Loved One; incidentally, Waugh himself called Wodehouse “the Master”). At the time, the eminently reasonable Cynthia Haven offered what I now deem to be appropriate pushback, observing that I brought a lot of “post-modern baggage” into my reading. My “take” on that novel’s Catholic dialogue was, I now realize after diving into Waugh again, driven by a cocky yahooism that is perhaps better deployed while knocking back pints in a sports bar and claiming that you’re a big fan of the team everybody else is cheering for. Never mind that the names of the players are only lodged in your memory by the blinding Chryon reminders and the bellowing cries of histrionic announcers that work together to perfect a sense-deadening television experience.

Anyway, I’ll leave cloud cuckoos like Dave Eggers to remain dishonest and pretend they never despised great novels. I’d rather be candid about where I may have strayed in my literary judgement and how I have tried to reckon with it. In a literary climate of “No haters” (and thus no chances), we are apparently no longer allowed to (a) voice dissenting opinions or (b) take the time to reassess our youthful follies and better appreciate a novel that rubbed us the wrong way on the first read. Wrestling with fiction should involve expressing our hesitations and confessing our evolving sensibilities and perceiving what a problematic author did right. And so here we are. It has taken many months to get here, but it does take time to articulate a personal contradiction.

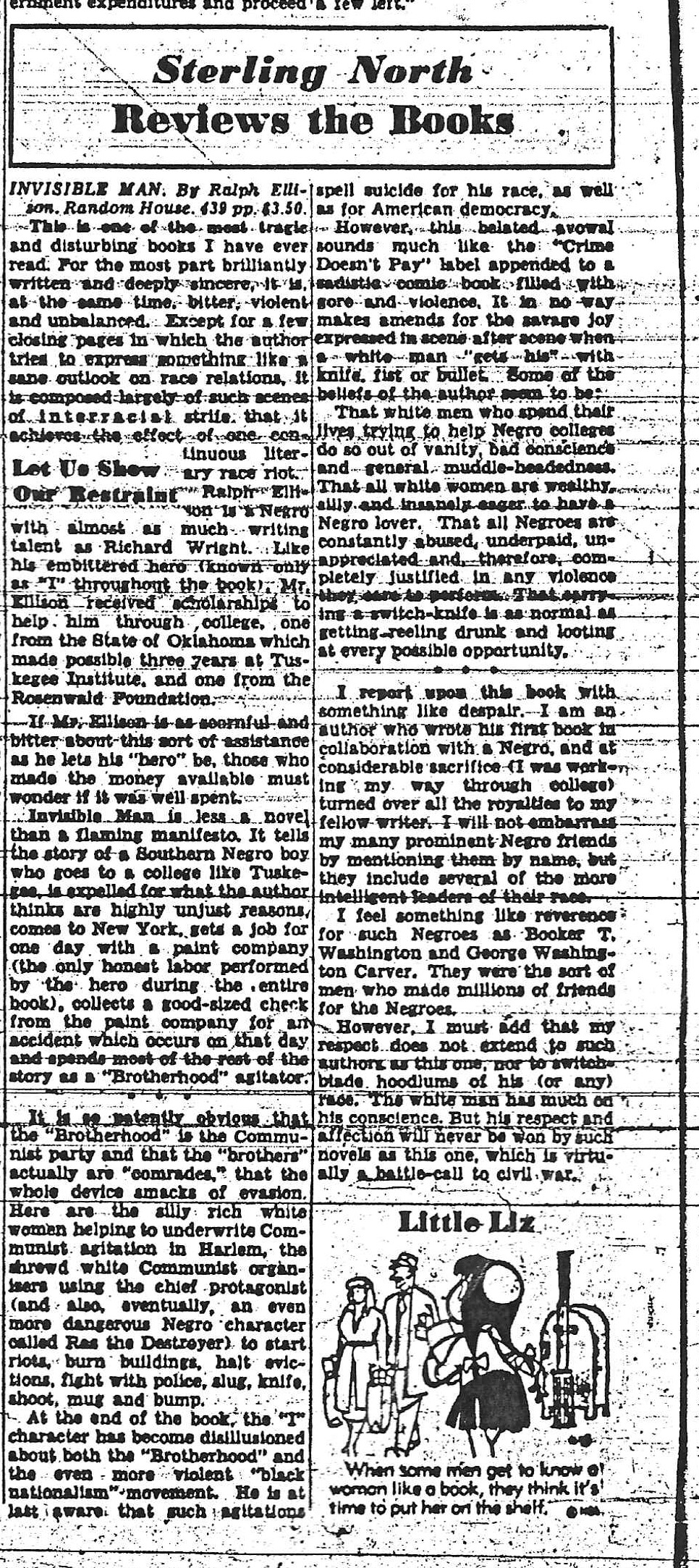

So here goes: As much as I appreciate Scoop‘s considerable merits (particularly the fine and often hilarious satire when the book takes place on Waugh’s home turf), I cannot find it within me to endorse this novel’s abysmally tone-deaf observations on a fictitious Abyssinia — here, Ishmaelia. There are unsophisticated thoughts cloaked beneath the light fluidity of Waugh’s exacting pen that many of his acolytes — including The Observer‘s Robert McCrum and NPR’s Alexander Nazaryan — refuse to acknowledge. There’s no other way to say this, but Waugh is more nimble with his gifts when he bakes his pies with an anglophonic upper crust. And that ugly truth should give any reader or admirer great pause. (Even Selina Hastings, one of his biographers, was forced to concede this. And McCrum, to his credit, does at least write that “Scoop derives less inspiration from Ethiopia,” although this is a bit like stating that Paul Manafort merely muttered a little white lie.) Waugh’s limitations in Scoop are not as scabrous as Black Mischief — a novel so packed with racism that it’s almost the literary equivalent to Louis C.K.’s recent attempts at a comeback. But his “insights” into Africa are still very bad, despite all the other rich wit contained within the book. Waugh cannot see anyone who does not share his lily-white complexion as human. His creatively bankrupt view of Africans as bloodthirsty cannibals or “crapulous black servants” or “a natty young Negro smoking from a long cigarette holder” carries over from Black Mischief. “A pious old darky named Mr. Samuel Smiles Jackson” is installed President. I was rankled by the constant cries of “Boy!” from the assorted journos, late risers who complain about not getting swift servitude with a smile. (“Six bloody black servants and no breakfast,” sneers the entitled Corker at one point.) Even the potentially interesting politics behind Ishmaelia’s upheaval are coarse and general, with the arrival of Dr. Benito at a press conference described in one paragraph with a contrast of “blacks” and “whites” that show the force and timing of a man determined to be vituperative, but without substantive subtlety. One of the book’s jokes involves a nonexistent city on the nation’s map identified as “Laku,” which is Ishmaelite for “I don’t know.” And while it does allow for a decent setup in which numerous journalists expend lavish resources to find Laku for their stories, I suspect that this is really Waugh confessing he doesn’t know and can’t know because he doesn’t want to.

Still, in approaching Scoop, I was determined to give this book more care than what I doled out to Brideshead. Not only did I spend a few months rereading all of Waugh’s novels up through Brideshead, finding them considerably richer than I did on my first two canon reads, but I also dived into the Selina Hastings and Martin Stannard biographies, along with numerous other texts pertaining to Scoop. And one cannot completely invalidate Waugh’s talent:

“Why, once Jakes went out to cover a revolution in one of the Balkan capitals. He overslept in a carriage, woke up at the wrong station, didn’t know any different, got out, went straight to a hotel, and cabled off a thousand-word story about barricades in the streets, flaming churches, machine guns answering the rattle of his typewriter as he wrote, a dead child, like a broken doll, spreadeagled in the deserted roadway below his window — you know. Well, they were pretty surprised at his office, getting a story like that from the wrong country, but they trusted Jakes and splashed it in six national newspapers. That day every special in Europe got orders to rush to the new revolution.”

This is pitch-perfect Waugh. Sadly, the wanton laziness of journalists and willful opportunism of newspaper publishers remain very applicable eighty-one years after Scoop‘s publication. In 2015, a Hardin County newspaper misreported that the local sheriff had said that “those who go into the law enforcement profession typically do it because they have a desire to shoot minorities.” And this was before The New York Times became an apologist outlet for Nazis (the original title of that linked article was “In America’s Heartland, the Nazi Sympathizer Next Door”) and didn’t even bother to fact-check an infamous climate change denial article from Bret Stephens published on April 28, 2017.

So Scoop does deserve our attention in an age devoted to “alternative facts” and a vulgar leader who routinely squeezes savage whoppers through his soulless teeth. Waugh uses a familiar but extremely effective series of misunderstandings to kickstart his often razor-sharp sendup, whereby a hot writer by the name of John Courtney Boot is considered to be the ideal candidate to cover a war in Ishamelia for The Daily Beast (not to be confused with the present Daily Beast founded by Tina Brown, who took the name from Waugh — and, while we’re on the subject of contemporary parallels, Scoop also features a character by the name of Nannie Bloggs, quite fitting in an epoch populated with dozens of nanny blogs). John Boot is confused with William Boot, a bucolic man who writes a nature column known as Lush Places and believes himself to be in trouble with the top brass for substituting “beaver” with “great crested grebe” in a recent installment. He is sent to cover a war that nobody understands.

The novel is funny and thrilling in its first one hundred pages, with Waugh deftly balancing his keen eye for decor (he did study architecture) with these goofy mixups. Rather tellingly, however, Waugh does spend a lot of time with William Boot in transit to Ishamelia, almost as if Waugh is reluctant to get to the country and write about the adventure. And it is within the regions of East Africa that Waugh is on less firm footing, especially when he strays from the journalists. Stannard has helpfully observed that, of all Waugh’s pre-war novels, Scoop was the most heavily edited and that it was the “political” sections with which Waugh had “structural problems.” But Scoop‘s problems really amount to tonal ones. Where Erskine Caldwell’s Tobacco Road (ML #91) brilliantly holds up a mirror to expose the audience’s assumptions about people (with the novel’s Broadway adaptation inspiring a tremendously interesting Ralph Ellison essay called “An Extravagance of Laughter,” which many of today’s self-righteous vigilantes should read), Scoop seems more content to revel in its atavistic prejudices.

In 2003, Christopher Hitchens gently bemoaned the “rank crudity” of Waugh’s childish names for side characters. And I think he was right to pinpoint Waugh’s declining powers of invention. For all of Scoop‘s blazing panoramas and descriptive sheen (the prose committed to the Megalopilitan offices is brilliant), the ultimate weakness of the book is that Waugh seems incapable of imbuing Ishamelia with the same inventive life with which he devotes to England. When one looks at the travel writing that came before this, even the high points of Waugh in Abyssinia are the sections where he bitches about his boredom.

Waugh’s writing was often fueled by a vicious need for revenge and an inability to let things go. Take the case of Charles Crutwell, the Hertford dean who praised Waugh on his writing and awarded him an Oxford scholarship as a young man. Waugh proceeded to be incredibly lazy about his studies, deciding that he had earned this financial reward, that he no longer needed to exert himself in any way, and that he would spend his time boozing it up and getting tight with his mates. Crutwell told Waugh that he needed to take his research more seriously. He could have had Waugh expelled, but he didn’t. And for this, Crutwell became the target of Waugh’s savage barbs throughout much of his early writing and many of his novels. In Decline and Fall, you’ll find Toby Crutwell as an insane burglar turned MP. In Vile Bodies, a “Captain Crutwell” is the snobby member of the Committee of the Ladies’ Conservative Association at Chesham Bois. There’s a Crutwell in Black Mischief and A Handful of Dust. Waugh’s story “Mr. Loveday’s Little Outing” was originally titled “Mr. Crutwell’s Little Outing.” And in one of Scoop‘s supererogatory chapters, William Boot meets a General Crutwell who has had numerous landmarks named after him. Keep in mind that this is sixteen years after the events in Hertford. You want to take Waugh aside, buy him a beer, and say, “Bro, walk away.”

Now I have to confess that this type of brutal targeted satire was catnip for me at a certain impressionable age that lingered embarrassingly long into my late thirties. The very kind George Saunders tried to get me to understand this twelve years ago during an episode of my old literary podcast, The Bat Segundo Show, in which we were discussing the way Sacha Baron Cohen singled out people with total malice. Cohen’s recent television series Who is America certainly upheld Saunders’s point. Of course, I stubbornly pushed back. Because ridicule is a hell of a drug. Just ask anyone with a Twitter account. But I now understand, especially after contending with Waugh again, that effective satire needs to be more concerned with exposing and virulently denouncing those in actual power, railing against the tyrannical institutions that diminish individual lives, and, of course, exposing the follies of human behavior. Waugh does this to a large extent in Scoop and his observations about newspapermen running up large tabs on their expense accounts and manipulating the competition are both funny and beautiful, but he also appears to have been operating from an inferiority complex, an intense need for victory against his perceived oppressors and something that, truth be told, represents a minor but nevertheless troubling trait I recognize in myself and that has caused much of my own writing and communications with people to be vehemently misunderstood, if not outright distorted into libelous and untrue allegations. When your motivation to write involves the expression of childish snubs and pedantic rage without a corresponding set of virtues, it is, from my standpoint, failed satire. And I don’t know about you, but my feeling is that, if you’re still holding a grudge against someone after five or six years, then the issue is no longer about the person who wronged you, but about a petty and enduring narcissism on behalf of the grudgeholder. What precisely do these many Crutwells add to Waugh’s writing? Not much, to tell you the truth.

We do know that, when Waugh covered Abyssinia, he wrote in a letter to Penelope Betjeman, “I am a very bad journalist, well only a shit could be good on this particular job.” So perhaps there was a part of Waugh that needed to construct a biting novel from his own toxic combination of arrogance and self-loathing.

But Waugh’s biggest flaw as a writer, however great his talent, was his inability to summon empathy or a humanistic vision throughout his work, even if it is there in spurts in Brideshead and perhaps best realized in his finest novel, A Handful of Dust. When William Boot foot falls in love with Kätchen, a poorly realized character at best, Waugh has no interest in portraying Boot’s feelings as anything more than that of a dopey cipher who deserves our contempt: “For twenty-three years he had remained celibate and and heart-whole; landbound. Now for the first time he was far from sure, submerged among deep waters, below wind and tide, where huge trees raised their spongy flowers and monstrous things without fur or feather, wing or foot, passed silently in submarine twilight. A lush place.” It is one thing to present Boot clumsily setting up an unnecessary canoe or showing the way he gets hoodwinked over a heavy package of stones or not understanding basic journalism jargon and to let Boot’s bumbling behavior (or, for that matter, the apposite metaphor of a three-legged dog barking in a barrel just outside Kätchen’s home) speak for itself. It is quite another thing to stack the deck against your protagonist with a passage like this, however eloquently condemned. What Waugh had not learned from Wodehouse was that there was a way of both recognizing the ineptitude of a dunderhead while also humanizing his feelings. You can lay down as many barbs as you like in art, but, at a certain point, if you’re any good, the artistic expression itself has to evolve beyond mere virtuosic style. This, in my view, is the main reason why Waugh crumbled and why I think his standing should be reassessed. The vindictiveness in Black Mischief, however crucially transgressive at the time, still represented a failure of creative powers. All Waugh had left at the end was a bitter nostalgia for a lost Britannia and a fear of modernity, which amounted to little more than an old man pining for the good old days by the time Waugh got to his wildly overrated Sword of Honour trilogy (and by the time Louis C.K. returned on stage with his first full set littered with racism, transphobia, and scorn for the young generation). If Waugh had learned to see the marvel of a changing world and if he had embraced human progress rather than fleeing from it, he might have produced more substantive work. But, hey, here I am talking about the guy nearly a century later, largely because he’s on a list. Still, even today, young conservative men have adopted the tweedy analog look of a “better time.” So maybe the joke’s on me. Thankfully the next Waugh novel book I have to write about, A Handful of Dust (ML #34), is a legitimate masterpiece. So I will try to give Waugh a more generous hearing when we get there in a few years. For now, I’m trying to shake off his seductive spite as well as the few remaining dregs of my own.

Next Up: Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms!

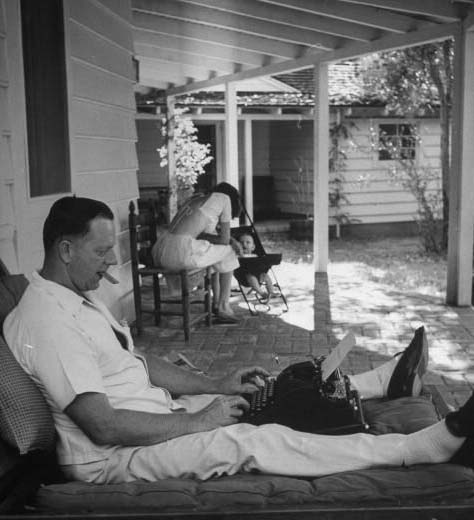

Like many great writers of the 20th century, Erskine Caldwell experienced difficulties keeping his dick in his pants. While such bulging foibles aren’t normally the stuff of pertinent consideration, Erskine Caldwell Reconsidered (edited by Edwin T. Arnold and published by the University Press of Mississippi) is the rare academic volume offering a partially persuasive case that Caldwell’s philandering was one throbbing element of the creative package.

Like many great writers of the 20th century, Erskine Caldwell experienced difficulties keeping his dick in his pants. While such bulging foibles aren’t normally the stuff of pertinent consideration, Erskine Caldwell Reconsidered (edited by Edwin T. Arnold and published by the University Press of Mississippi) is the rare academic volume offering a partially persuasive case that Caldwell’s philandering was one throbbing element of the creative package.