(This is the tenth entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: The Power Broker.)

When I first made my bold belly flop into the crisp waters of Ralph Ellison’s deep pool earlier this year, I felt instantly dismayed that it would be a good decade before I could perform thoughtful freestyle in response to his masterpiece Invisible Man (ML Fiction #19). As far as I’m concerned, that novel’s vivid imagery, beginning with its fierce and intensely revealing Battle Royale scene and culminating in its harrowing entrapment of the unnamed narrator, stands toe-to-toe with Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March as one of the most compelling panoramas of mid-20th century American life ever put to print, albeit one presented through a more hyperreal lens.

When I first made my bold belly flop into the crisp waters of Ralph Ellison’s deep pool earlier this year, I felt instantly dismayed that it would be a good decade before I could perform thoughtful freestyle in response to his masterpiece Invisible Man (ML Fiction #19). As far as I’m concerned, that novel’s vivid imagery, beginning with its fierce and intensely revealing Battle Royale scene and culminating in its harrowing entrapment of the unnamed narrator, stands toe-to-toe with Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March as one of the most compelling panoramas of mid-20th century American life ever put to print, albeit one presented through a more hyperreal lens.

But many of today’s leading writers, ranging from Ta-Nehisi Coates to Jacqueline Woodson, have looked more to James Baldwin as their truth-telling cicerone, that fearless sage whose indisputably hypnotic energy was abundant enough to help any contemporary humanist grapple with the nightmarish realities that America continues to sweep under its bright plush neoliberal rug. At a cursory glance, largely because Ellison’s emphasis was more on culture than overt politics, it’s easy to see Ellison as a complacent “Maybe I’m Amazed” to Baldwin’s gritty “Cold Turkey,” especially when one considers the risk-averse conservatism which led to Ellison being attacked as an Uncle Tom during a 1968 panel at Grinnell College along with his selfish refusal to help emerging African-American authors after his success. But according to biographer Arnold Rampersad, Baldwin believed Ralph Ellison to be the angriest person he knew. And if one dives into Ellison’s actual words, Shadow and Act is an essential volume, which includes one of the most thrilling Molotov cocktails ever pitched into the face of a clueless literary critic, that is often just as potent and as lapel-grabbing as Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time.

For it would seem that while Negroes have been undergoing a process of “Americanization” from a time preceding this birth of this nation — including the fusing of their blood lines with other non-African strains, there has been a stubborn confusion as to their American identity. Somehow it was assumed that the Negroes, of all the diverse American peoples, would remain unaffected by the climate, the weather, the political circumstances — from which not even slaves were exempt — the social structures, the national manners, the modes of production and the tides of the market, the national ideals, the conflicts of values, the rising and falling of national morale, or the complex give and take of acculturalization which was undergone by all others who found their existence within the American democracy.

This passage, taken from an Ellison essay on Amiri Baraka’s Blues People, is not altogether different from Baldwin’s view of America as “a paranoid color wheel” in The Evidence of Things Not Seen, where Baldwin posited that a retreat into the bigoted mystique of Southern pride represented the ultimate denial of “Americanization” and thus African-American identity. Yet the common experiences that cut across racial lines, recently investigated with comic perspicacity on a “Black Jeopardy” Saturday Night Live sketch, may very well be a humanizing force to counter the despicable hate and madness that inspires uneducated white males to desecrate a Mississippi black church or a vicious demagogue to call one of his supporters “a thug” for having the temerity to ask him to be more respectful and inclusive.

Ellison, however, was too smart and too wide of a reader to confine these sins of dehumanization to their obvious targets. Like Baldwin and Coates and Richard Wright, Ellison looked to France for answers and, while never actually residing there, he certainly counted André Malraux and Paul Valéry among his hard influences. In writing about Richard Wright’s Black Boy, Ellison wisely singled out critics who failed to consider the full extent of African-American humanity even as they simultaneously demanded an on-the-nose and unambiguous “explanation” of who Wright was. (And it’s worth noting that Ellison himself, who was given his first professional writing gig by Wright, was also just as critical of Wright’s ideological propositions as Baldwin.) Ellison described how “the prevailing mood of American criticism has so thoroughly excluded the Negro that it fails to recognize some of the most basic tenets of Western democratic thought when encountering them in a black skin” and deservedly excoriated whites for seeing Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson merely as the ne plus ultra of African-American artistic innovation rather than the beginning of a great movement.

At issue, in Ellison’s time and today, is the degree to which any individual voice is allowed to express himself. And Ellison rightly resented any force that would stifle this, whether it be the lingering dregs of Southern slavery telling the African-American how he must act or who he must be in telling his story as well as the myopic critics who would gainsay any voice by way of their boxlike assumptions about other Americans. One sees this unthinking lurch towards authoritarianism today with such white supremacists as Jonathan Franzen, Lionel Shriver, and the many Brooklyn novelists who, despite setting their works in gentrified neighborhoods still prominently populated by African-Americans, fail to include, much less humanize, black people who still live there.

At issue, in Ellison’s time and today, is the degree to which any individual voice is allowed to express himself. And Ellison rightly resented any force that would stifle this, whether it be the lingering dregs of Southern slavery telling the African-American how he must act or who he must be in telling his story as well as the myopic critics who would gainsay any voice by way of their boxlike assumptions about other Americans. One sees this unthinking lurch towards authoritarianism today with such white supremacists as Jonathan Franzen, Lionel Shriver, and the many Brooklyn novelists who, despite setting their works in gentrified neighborhoods still prominently populated by African-Americans, fail to include, much less humanize, black people who still live there.

“White supremacist” may seem like a harshly provocative label for any bumbling white writer who lacks the democratic bonhomie to leave the house and talk with other people and consider that those who do not share his skin color may indeed share more common experience than presumed. But if these writers are going to boast about how their narratives allegedly tell the truth about America while refusing to accept challenge for their gaping holes and denying the complexity of vital people who make up this great nation, then it seems apposite to bring a loaded gun to a knife fight. If we accept Ellison’s view of race as “an irrational sea in which Americans flounder like convoyed ships in a gale,” then it is clear that these egotistical, self-appointed seers are buckling on damaged vessels hewing to shambling sea routes mapped out by blustering navigators basking in white privilege, hitting murky ports festooned with ancient barnacles that they adamantly refuse to remove.

Franzen, despite growing up in a city in which half the population is African-American, recently told Slate‘s Isaac Chotiner that he could not countenance writing about other races because he has not loved them or gone out of his way to know them and thus excludes non-white characters from his massive and increasingly mediocre novels. Shriver wrote a novel, The Mandibles, in which the only black characters are (1) Leulla, bound to a chair and walked with a leash, and (2) Selma, who speaks in a racist Mammy patois (“I love the pitcher of all them rich folk having to cough they big piles of gold”). She then had the effrontery to deliver a keynote speech at the Brisbane Writers Festival arguing for the right to “try on other people’s hats,” failing to understand that creating dimensional characters involves a great deal more than playing dress-up at the country club. She quoted from a Margot Kaminski review of Chris Cleave’s Little Bee that offered the perfectly reasonable consideration, one that doesn’t deny an author’s right to cross boundaries, that an author may wish to take “special care…with a story that’s not implicitly yours to tell.” Such forethought clearly means constructing an identity that is more human rather than crassly archetypal, an eminently pragmatic consideration on how any work of contemporary art should probably reflect the many identities that make up our world. But for Shriver, a character should be manipulated at an author’s whim, even if her creative vagaries represent an impoverishment of imagination. For Shriver, inserting another nonwhite, non-heteronormative character into The Mandibles represented “issues that might distract from my central subject moment of apocalyptic economics.” Which brings us back to Ellison’s question of “Americanization” and how “the diverse American peoples” are indeed regularly affected by the decisions of those who uphold the status quo, whether overtly or covertly.

Writer Maxine Benba-Clarke bravely confronted Shriver with the full monty of this dismissive racism and Shriver responded, “When I come to your country. I expect. To be treated. With hospitality.” And with that vile and shrill answer, devoid of humanity and humility, Shriver exposed the upright incomprehension of her position, stepping from behind the arras as a kind of literary Jan Smuts for the 21st century.1

If this current state of affairs represents a bristling example of Giambattista Vico’s corsi e ricorsi, and I believe it does, then Ellison’s essay, “Twentieth-Century Fiction and the Black Mask of Humanity,” astutely demonstrates how this cultural amaurosis went down before, with 20th century authors willfully misreading Mark Twain, failing to see that Huck’s release of Jim represented a moment that not only involved recognizing Jim as a human being, but admitting “the evil implicit in his ’emancipation'” as well as Twain accepting “his personal responsibility in the condition of society.” With great creative power comes great creative responsibility. Ellison points to Ernest Hemingway scouring The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn merely for its technical accomplishments rather than this moral candor and how William Faulkner, despite being “the greatest artist the South has produced,” may not be have been quite the all-encompassing oracle, given that The Unvanquished‘s Ringo is, despite his loyalty, devoid of humanity. In another essay on Stephen Crane, Ellison reaffirms that great art involves “the cost of moral perception, of achieving an informed sense of life, in a universe which is essentially hostile to man and in which skill and courage and loyalty are virtues which help in the struggle but by no means exempt us from the necessary plunge into the storm-sea-war of experience.” And in the essays on music that form the book’s second section (“Sound and the Mainstream”), Ellison cements this ethos with his personal experience growing up in the South. If literature might help us to confront the complexities of moral perception, then the lyrical, floating tones of a majestic singer or a distinctive cat shredding eloquently on an axe might aid us in expressing it. And that quest for authentic expression is forever in conflict with audience assumptions, as seen with such powerful figures as Charlie Parker, whom Ellison describes as “a sacrificial figure whose struggles against personal chaos…served as entertainment for a ravenous, sensation-starved, culturally disoriented public which had but the slightest notion of its real significance.”

What makes Ellison’s demands for inclusive identity quite sophisticated is the vital component of admitting one’s own complicity, an act well beyond the superficial expression of easily forgotten shame or white guilt that none of the 20th or the 21st century writers identified here have had the guts to push past. And Ellison wasn’t just a writer who pointed fingers. He held himself just as accountable, as seen in a terrific 1985 essay called “An Extravagance of Laughter” (not included in Shadow and Act, but found in Going with the Territory), in which Ellison writes about how he went to the theatre to see Jack Kirkland’s adaptation of Erskine Caldwell’s Tobacco Road. (I wrote about Tobacco Road in 2011 as part of this series and praised the way that this still volatile novel pushes its audience to confront its own prejudices against the impoverished through remarkably flamboyant characters.) Upon seeing wanton animal passion among poor whites on the stage, Ellison burst into an uncontrollable paroxysm of laughter, which emerged as he was still negotiating the rituals of New York life shortly after arriving from the South. Ellison compared his reaction, which provoked outraged leers from the largely white audience, to an informal social ceremony he observed while he was a student at Tuskegee that involved a set of enormous whitewashed barrels labeled FOR COLORED placed in public space. If an African-American felt an overwhelming desire to laugh, he would thrust his head into the pit of the barrel and do so. Ellison observes that African-Americans “who in light of their social status and past condition of servitude were regarded as having absolutely nothing in their daily experience which could possibly inspire rational laughter.” And the expression of this inherently human quality, despite being a cathartic part of reckoning with identity and one’s position in the world, was nevertheless positioned out of sight and thus out of mind.

When I took an improv class at UCB earlier this year, I had an instructor who offered rather austere prohibitions to any strain of humor considered “too dark” or “punching down,” which would effectively disqualify both Tobacco Road and the Tuskegee barrel ritual that Ellison describes.2 These restrictions greatly frustrated me and a few of my classmates, who didn’t necessarily see the exploration of edgy comic terrain as a default choice, but merely one part of asserting an identity inclusive of many perspectives. I challenged the notion of confining behavior to obvious choices and ended up getting a phone call from the registrar, who was a smart and genial man and with whom I ended up having a friendly and thoughtful volley about comedy. I had apparently been ratted out by one student, who claimed that I was “disrupting” the class when I was merely inquiring about my own complicity in establishing base reality. In my efforts to further clarify my position, I sent a lengthy email to the instructor, one referencing “An Extravagance of Laughter,” and pointed out that delving into the uncomfortable was a vital part of reckoning with truth and ensuring that you grew your voice and evolved as an artist. I never received a reply. I can’t say that I blame him.

Ellison’s inquiry into the roots of how we find common ground with others suggests that we may be able to do so if we (a) acknowledge the completeness of other identities and (b) allow enough room for necessary catharsis and the acknowledgment of our feelings and our failings as we take baby steps towards better understanding each other.

The most blistering firebomb in the book is, of course, the infamous essay “The World and the Jug,” which demonstrates just what happens when you assume rather than take the time to know another person. It is a refreshingly uncoiled response that one could not imagine being published in this age of “No haters” reviewing policies and genial retreat from substantive subjects in today’s book review sections. Reacting to Irving Howe’s “Black Boys and Native Sons,” Ellison condemns Howe for not seeing “a human being but an abstract embodiment of living hell” and truly hammers home the need for all art to be considered on the basis of its human experience rather than the spectator’s constricting inferences. Howe’s great mistake was to view all African-American novels through the prism of a “protest novel” and this effectively revealed his own biases against what black writers had to say and very much for certain prerigged ideas that Howe expected them to say. “Must I be condemned because my sense of Negro life was quite different?” writes Ellison in response to Howe roping him in with Richard Wright and James Baldwin. And Ellison pours on the vinegar by not only observing how Howe self-plagiarized passages from previous reviews, but how his intractable ideology led him to defend the “old-fashioned” violence contained in Wright’s The Long Dream, which, whatever its merits, clearly did not keep current with the changing dialogue at the time.

Shadow and Act, with its inclusion of interviews and speeches and riffs on music (along with a sketch of a struggling mother), may be confused with a personal scrapbook. But it is, first and foremost, one man’s effort to assert his identity and his philosophy in the most cathartic and inclusive way possible. We still have much to learn from Ellison more than fifty years after these essays first appeared. And while I will always be galvanized by James Baldwin (who awaits our study in a few years), Ralph Ellison offers plentiful flagstones to face the present and the future.

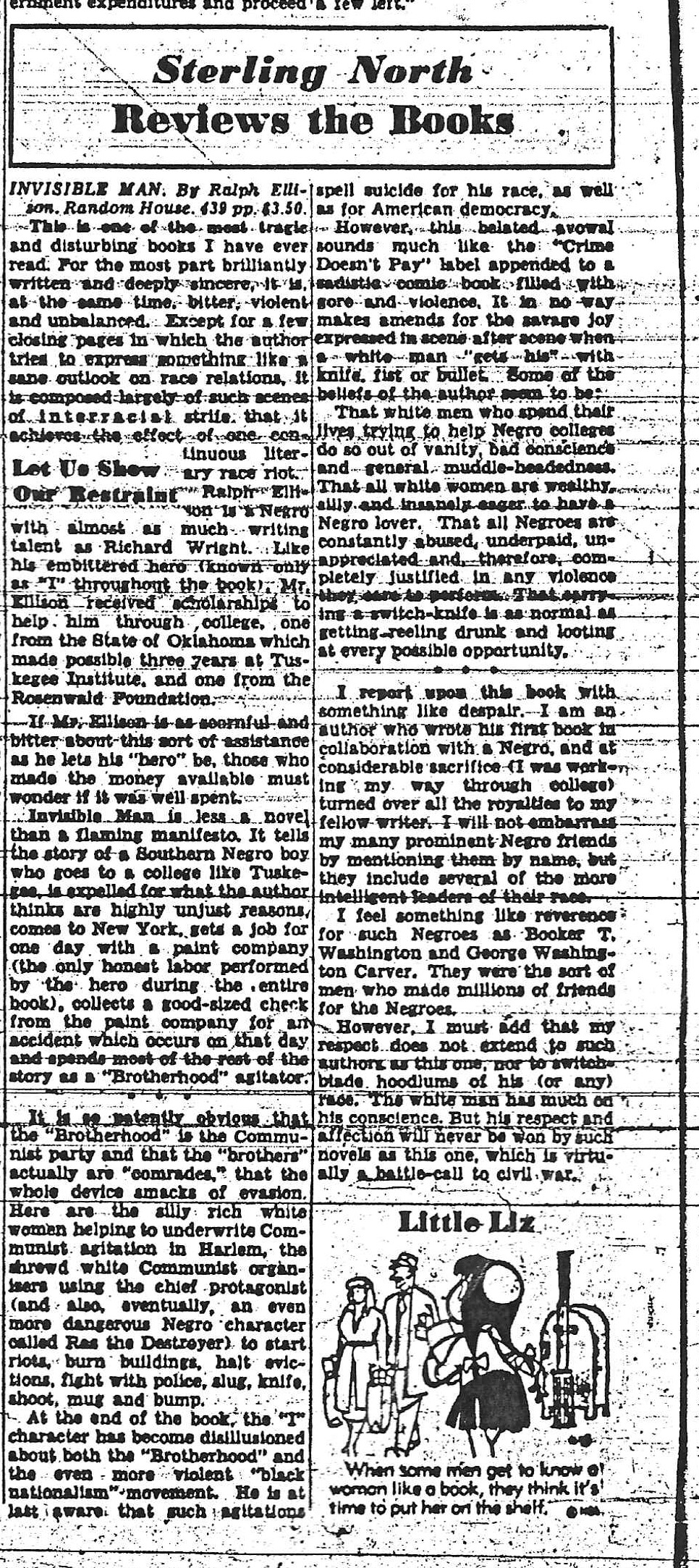

SUPPLEMENT: One of the great mysteries that has bedeviled Ralph Ellison fans for decades is the identity of the critic who attacked Invisible Man as a “literary race riot.” In a Paris Review interview included in Shadow and Act, Ellison had this to say about the critic:

But there is one widely syndicated critical bankrupt who made liberal noises during the thirties and has been frightened ever since. He attacked my book as a “literary race riot.”

With the generous help of Ellison’s biographer Arnold Rampersad (who gave me an idea of where the quote might be found in an email volley) and the good people at the New York Public Library, I have tracked down the “widely syndicated critical bankrupt” in question.

His name is Sterling North, best known for the children’s novel Rascal in 1963. He wrote widely popular (and rightly forgotten) children’s books while writing book reviews for various newspapers. North was such a vanilla-minded man that he comics “a poisonous mushroom growth” and seemed to have it in for any work of art that dared to do something different — or that didn’t involve treacly narratives involving raising baby raccoons.

His name is Sterling North, best known for the children’s novel Rascal in 1963. He wrote widely popular (and rightly forgotten) children’s books while writing book reviews for various newspapers. North was such a vanilla-minded man that he comics “a poisonous mushroom growth” and seemed to have it in for any work of art that dared to do something different — or that didn’t involve treacly narratives involving raising baby raccoons.

And then, in the April 16, 1952 issue of the New York World-Telegram, he belittled Ellison’s masterpiece, writing these words:

This is one of the most tragic and disturbing books I have ever read. For the most part brilliantly written and deeply sincere, it is, at the same time, bitter, violent and unbalanced. Except for a few closing pages in which the author tries to express something like a sane outlook on race relations, it is composed largely of such scenes of interracial strife that it achieves the effect of one continuous literary race riot. Ralph Ellison is a Negro with almost as much writing talent as Richard Wright. Like his embittered hero (known only as “I’ throughout the book, Mr. Ellison received scholarships to help him through college, one from the State of Oklahoma which made possible three years at the Tuskegee Institute, and one from the Rosenwald Foundation.

If Mr. Ellison is as scornful and bitter about this sort of assistance as he lets his “hero” be, those who made the money available must wonder if it was well spent.

North’s remarkably condescending words offer an alarming view of the cultural oppression that Ellison was fighting against and serve as further justification for Ellison’s views in Shadow and Act. Aside from his gross mischaracterization of Ellison’s novel, there is North’s troubling assumptions that Ellison should be grateful in the manner of an obsequious and servile stereotype, only deserves a scholarship if he writes a novel that fits North’s limited idea of what African-American identity should be, and that future white benefactors should think twice about granting opportunities for future uppity Ellisons.

It’s doubtful that The Sterling North Society will recognize this calumny, but this is despicable racism by any measure. A dive into North’s past also reveals So Dear to My Heart, a 1948 film adaptation of North’s Midnight and Jeremiah that reveled in Uncle Tom representations of African-Americans.

North’s full review of The Invisible Man can be read below:

Next Up: James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough!

Reading this collection and having this misfortune to experience some of these

Reading this collection and having this misfortune to experience some of these