(This is the fortieth entry in The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: From Here to Eternity.)

Most of the largely sexist pigs who came up with the Modern Library canon were ancient men more fond of oinking and logrolling rather than upholding literary standards. (There was only one woman among these judges: to evoke a recent Marc Maron bit, “It was a different time”).

Most of these judges are now dead. Just as the regressive viewpoints they tapped within their 20th century hearts are now mostly pushing up the daisies. (Thank you, #metoo movement!) Oddball Christopher Cerf is the only judge still alive and I invite him to verbal pistols at dawn (or perhaps, more accurately, a feisty reckoning over a cup of morning tea) if he wants to respond to the list’s hideous gender imbalance. The remaining judiciary corpses include Gore Vidal (dead, past his prime in ’98), Daniel J. Boorstin (dead, past his prime in ’98), Shelby Foote (dead, covert Confederacy apologist, we’ll be getting to him in a few years, past his prime in ’98), Vartan Gregorian (dead, but, from all reports, a decent dude), A.S. Byatt (GOAT, literally just died in November, should have pushed back harder against these testosterone-charged fossils, being a Willa Cather fan seems to be her only fault), Edmund Morris (dead, past his prime in ’98 and about to destroy his career with Dutch), John Richardson (dead, past his prime in ’98), Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. (dead, past his prime in ’98), and William Styron (dead, perilously close to being done in ’98, but dammit he at least gave us Darkness Visible, which was rightly included on the Modern Library nonfiction list).

Anyway, it says a great deal about the casual misogyny of these then doddering judges that a hopeless and unremarkable square like Willa Cather (the kind of teeming bore that other teeming bores genuflect to) somehow secured a much higher slot than such indisputable virtuosos as Iris Murdoch, Jean Rhys, and Muriel Spark. It says a great deal that Willa “Cream Corn” Cather — a plodding rustic rube without a soupçon of edge who wrote sentences so loathsome that, only ten minutes after reading an especially awful exemplar, I sprout wings from my back, descend with my fangs upon innocents in Manhattan, and destroy random chevron-studded façades and angelic statuary mounted on art deco skyscrapers hundreds of feet above the streets (if you Google around, you’ll find TikToks out there depicting my frightening transmutation; it is a display that is not for the faint of heart) — is apparently more worthy of commendation than Toni Morrison, Margaret Atwood, Flannery O’Connor, Octavia Butler, Angela Carter, Zora Neale Hurston, Jane Bowles, Ursula K. Le Guin, or Harper Lee, who were all denied a single spot on the list.

In 1998, did the Modern Library Judges fear what was then called an “outspoken” woman? Did they wish to consign “innovation” solely to men? Were they unsettled by the many waves of feminism? Did they try to argue that an insufferable reactionary goody little two-shoes like Cather was a feminist because she exposed spousal discontent through only the barest minimum amount of effort (see Alexandra in My Ántonia; if you think that’s a “radical” depiction of what women had to go through, I’ve got a bridge I can sell you here in Brooklyn) and because she was a closeted lesbian (even as she was tearing down other women of letters privately and publicly)?

At this point, we’ll probably never know. The likeliest scenario is that Cerf will stay mum and take the problematic history of these internal discussions to the grave. And let’s face the facts: the dude wouldn’t meet me for tea even if I whipped up a fun electro cover of one of his two hundred plus compositions for Sesame Street. (Yo, Chris, I’ve got terabytes of samples on my desktop! If a goofy emo punk version of “Monster in the Mirror” whipped up on my synth over the weekend will get you to cough up about this regrettable state of affairs, then I’ll do it! Seriously, that “wubba wubba wubba wubba woo woo woo” just begs to be rasped out in the manner similar to the late Can singer Damo Suzuki.)

The wondrous Dame Hermione Lee, who remains one of our greatest living literary scholars, has written a solid and truly admirable bio advocating for Cather. And while I appreciated Lee’s volume in much the same way that I will always stump for Carl Wilson’s Let’s Talk About Love, which reckons with the question on why so many people love Celine Dion, make no mistake: I consider anyone willing to go to the mat for Willa Cather to be some terminally unhip rooster without a shred of literary taste, the kind of unadventurous sod who would invite suicidal thoughts if you got cornered by him at a cocktail party. Lee gets special dispensation from me because she’s awesome — in large part because she wrote an invaluable Edith Wharton book (and I am, of course, crazy about Wharton). In fact, in quoting a passage from One of Ours that described junk, Lee identified a possible class-based literary divide between people like me who detest Cather and certain frou-frou bourgie types who think that she’s the cat’s pajamas (Christian Lander, you were so asleep at the wheel on the Cather front when you ran your excellent satirical blog!):

There is a hint that junk, once it starts ageing into antiques, might be seductive (an American writer with more entropic tendencies, like Nathanael West or Thomas Pynchon, would have loved that cellar) but, more often, junk is just pitiful, like the debris of Claude’s marital house: ‘How inherently mournful and ugly such objects were, when the feeling that had made them precious no longer existed!’ [OOO, p. 223] When Claude comes to the ‘dump-heap’ of the French battlefields, he has already been living in a civilization (Cather suggests) which has not needed a war to turn itself into rubbish.

You have to love that “Cather suggests” parenthetical that Lee drops into this cogent analysis. (Don’t worry, Hermione! We cool! I have Quincy Jones’s wonderful Sanford and Son theme playing in the back as I write this paragraph!) I guess you could say that I’m one of those readers who is more drawn to authors with “entropic tendencies.” I believe you can find beauty in damned near anything. Including junk. But Cather, despite stumping for the heartland, is more of a rebuking prude who never earned the right to be a snob. She’d rather throw out the junk and align herself with the sanitarium/cornflakes crowd: you know, the alternative medicine quacks sent up decades later in T.C. Boyle’s The Road to Wellville. I know you whipper-snappers are keeping up with me in our age of conspiracy theories, rampant cognitive decline, and unfounded character assassination on social media. Or at least I hope you are!

There’s also the question of whether Cather’s “literary sensibilities” can be entirely trusted. Of The Awakening, Cather had the audacity to write, “I shall not attempt to say why Miss Chopin has devoted so exquisite and sensitive, well-governed a style to so trite and sordid a theme.” One might say the same of a hopeless stiff like Cather herself, though she does not possess anything especially exquisite in her early works beyond country bumpkin exclamation marks. She condemned Mark Twain — arguably the greatest wit that American letters has ever produced — as a man of “limited mentality” and “neither a scholar, a reader or a man of letters and very little of a gentleman.”

Yes, I realize that all this was written in the nineteenth century and it is incredibly absurd to pick a fight with somebody who has been dead for nearly eight decades. But I’m telling you. After reading far more Cather than I needed to for this essay, I had actual nightmares about Cather strangling me while laughing in a menacing high-pitched titter. These dreams were so terrifying that I would not even wish them on my worst enemy. And if I have to write about this mediocre and humorless nitwit from Nebraska because she’s on this goddamned Modern Library list, well, in the immortal words of Bugs Bunny, them’s fighting words.

Let’s take a look at some of the trite and treacly bullshit that Cather was banging out when she rolled out the howitzers against these legends.

From “Paul’s Case”:

The young man was relating how his chief, now cruising in the Mediterranean, kept in touch with all the details of the business, arranging his office hours on his yacht just as though he were home, and “knocking off work enough to keep two stenographers busy.”

Note the redundancies here (“cruising in the Mediterranean” and “arranging his office hours on his yacht”). Even an oft prolix mofo like me recognizes this sentence as interminably long, presumably extended to cash in on the word rate.

Or how about this overwritten nonsense from “The Sculptor’s Funeral”?

The grating sound made by the casket, as it was drawn from the hearse, was answered by a scream from the house; the front door was wrenched open, and a tall, corpulent woman rushed out bareheaded into the snow and flung herself upon the coffin, shrieking: “My boy, my boy! And this is how you’ve come home to me!”

I’m very forgiving of melodrama in fiction, but this is unpardonable corn pudding with an objectively disagreeable sweetness that would be rightly laughed out of any MFA workshop today. The sequence of events here is all wrong. “Drawn from the hearse”? Well, where else would the casket come from? Some giant descending from the heavens? The attempt here to create poignant emotion falls flat with this overwrought dialogue. “My boy” was enough. But we get two in a row, followed by the kind of awful expository dialogue I go out of my way to avoid as a radio dramatist.

And then I read the soul-destroying novels. O Pioneers! was a vicious slog. The Song of the Lark — with its hideous reactionary parochialism and its incessant reliance upon gossip — will have you howling at the ceiling over how stiff and superficial it is. And My Ántonia? You’d honestly be better off spending your time listening to The Knack’s “My Sharona” on repeat for six hours.

Which finally brings us to Death Come for the Archbishop after a lot of throat-clearing. (Look, I’m trying to have fun here. My Cather deep dive was a deeply unpleasant reading experience!)

The common narrative propped up by Cather’s fusty and foolish boosters is that, much like Robert Johnson meeting the Devil, Cather went down to the Southwest (particularly Santa Fe) in the summer of 1925 and came back “reborn” with a renewed “sensitivity” for other cultures. But this, of course, is a lie. And it certainly doesn’t explain why Cather, much like a hopped up Zionist airhead denying Israel’s genocidal complicity, didn’t glom onto the indigenous people who lived in the region, but chose to fixate on the Christian authorities who longed to convert them.

I can see the Cather acolytes arriving at this point in my essay, suggesting that I have deliberately misread Death, which is oh so “sympathetic” to the indigenous people of New Mexico. But at what cost? Depicting Mexicans as noble savages? Emily of It Was Evening All Afternoon arrived at a similar conclusion in 2009. So did Kali Fajardo-Anstine over at LitHub. But why not just go straight to the text to see how docile and obliging the locals are?

When this strange yellow boy played it, there was softness and languor in the wire strings—but there was also a kind of madness; the recklessness, the call of wild countries which all these men had felt and followed in one way or another. Through clouds of cigar smoke, the scout and the soldiers, the Mexican rancheros and the priests, sat silently watching the bent head and crouching shoulders of the banjo player, and his seesawing yellow hand, which sometimes lost all form and became a mere whirl of matter in motion, like a patch of sand-storm.

A strong argument can be made that Cather was a white supremacist, particularly given her treatment of non-white characters in her odious final novel, Sapphira and the Slave Girl, which features hideous Black caricatures in the form of Bluebell and Lizzie. In an October 14, 1940 letter to Dorothy Canfield Fisher available at the online Willa Cather Archive (I am greatly indebted to Hermione Lee for her endnote), Cather wrote:

I loved especially playing with the darkey speech, which was deep down in my mind exactly like phonograph records. I could remember exactly what they said and the quality of the voice. Just wait till our wise young reviewers, such as Clifton and Louis, sadly call attention to the inconsistency in Till’s and Nancy’s speech,- never knowing that all well trained house servants spoke two languages: one with white people and one with their fellow negroes.

I hope this blatant racism and this boorish boasting helps you to understand why I have felt morally obliged to ratchet up the rage.

When Cather was at work on Death, a Cleveland Press reporter asked her what it was about. She replied, “America works on my mind like light on a photographic plate.” Jesus Christ, could you be any more pretentious? (Hermione Lee informs us that Cather, when making a trip to a writer’s colony as Death squeaked out of her precious mind, was “not remembered for her conviviality.” Which is a gentle way of telling us that Cather was completely fucking insufferable.)

To give Willa the Imperialist Prig some credit, I will say that Death Comes for the Archbishop is slightly better than the early turgid works, although that’s a bit like saying that the Limburger with the least amount of mold that you pick up from the charcuterie plate — you know, that stinky piece you nibble at out of politeness at a party simply because the poor host is blind and she had no idea that she was paring pieces from ancient heads that had been sitting in the fridge since the Clinton Administration — is the bomb.

Death opens with three cardinals and a bishop “talking business” about establishing a new vicarite in New Mexico, which Cather with full colonialist glee tells us is “a part of America recently annexed to the United States.” Bishop Ferrand, the missionary who headed out to the Old West, is ancient and weather-beaten and describes the desolate and fissure-ridden landscape for which these vaguely sinister religious mobsters hope to open up a franchise.

Jean Marie Latour, a thirty-five-year-old naif from Lake Ontario, is enlisted to be the point man converting all the Mexcians and the indigenous people who live in the region. And after these men of the cloth scoff over Latour’s intelligence (or lack thereof), Cather cuts to 1851, where Latour is on his way to Santa Fe. Cather does a decent job describing the limitless “uniform red hills” that Latour takes in on his journey. And there is a modicum of grit in this early chapter that, while a far cry from the satisfying description of Cormac McCarthy at his best, I largely enjoyed.

Unfortunately, after this promising start, my interest waned significantly when Latour began whining about not packing enough water for his journey and losing all of his possessions other than his books. It’s safe that Latour is a far cry from Chaucer’s many priests, G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown, or even Father John from M*A*S*H. He reveals himself quite rapidly to be an insufferable little shit and I started feeling sorry for Father Joseph Vaillant, Latour’s boyhood friend who accompanies him on the journey to Santa Fe. On the other hand, if you’re friends with a pompous windbag like Latour, then you probably deserve your shared misfortune.

As Father Latour is taken in by some locals, he finds a strange peace in the “bareness and simplicity” of the settlement. He quickly occupies space in a quietly domineering way and listens to the “simple” life stories of these people. I couldn’t help but wonder why a religious man like Latour was so ungrateful, but then I remembered how Cather herself hadn’t exactly been gracious to the many writers who tried to help her. Maybe the fact that Death can be read as a critique of religious imperialism is largely an accident.

Latour starts bragging about how great Americans are. You know, those white people who swooped in and destroyed the Mexican churches and stripped these good people of their religion? Those colonial assholes? They’re great, aren’t they? And, of course, Cather, by way of close narration through Latour, cannot feel any empathy for such debasement.

At this point, I began to loathe Latour with all my heart because of his cluelessness and his insensitivity. And I very much hoped that Cather would deliver on the promise of her title well before I was halfway through the book. Latour is very particular about a meal, telling some indigent to serve him a portion without chili because, as a Frenchman, he does “not like high seasoning.”

Not long after this, Latour is setting up his vicarite. And, of course, it’s Vaillant who is assigned to do all the cooking so that Latour can write endless letters in French. The bishop then takes the opportunity to bitch about the soup. Some friend this motherfucker is.

And even though condemning white privilege with this setup is easier than shooting monkeys in a barrel, I’ll give Cather some points for acknowledging hardscrabble reality:

The wiry little priest whose life was to be a succession of mountain ranges, pathless deserts, yawning canyons and swollen rivers, who was to carry the Cross into territories yet unknown and unnamed, who would wear down mules and horses and scouts and stage-drivers, tonight looked apprehensively at his superior and repeated, “No more , Jean. That is far enough.”

I suppose that Cather defenders will defend her belittling of Mexicans by pointing out how Vaillant is described as ugly. Maybe they’ll point to the way that Vaillant and Latour save an old Mexican slave named Sada. But their “help” involves this woman “obeying” the Padre and being ordered to go to church and pray. Sada really doesn’t have any agency other than wanting to return to her religion. And this, quite frankly, is nothing less than an insulting scene of religious tyranny and white privilege. As for the sinister murderer Buck Scales, it says quite a bit about Cather’s dormant xenophobia that his evil is defined equally in terms of interracial marriage: “All white men knew him for a dog and a degenerate—but to Mexican girls, marriage with an American meant coming up in the world. She had married him six years ago, and had been living with him ever since in that wretched house on the Mora trail.”

If you thought Jeanine Cummins was bad, try taking Willa Cather out for a spin. There’s no way I can defend Willa Cather and her repugnant insouciance in 2024. Her prose simply isn’t good enough for me to align myself with Hermione Lee. And I am pleased as punch that I will never have to read this mean and hideous writer ever again.

Next Up: Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer!

It can’t be an accident that the wildly underrated Julian MacLaren-Ross skewered the idea of reading Conrad as an upwardly mobile class aspiration in Of Love and Hunger. In Frog, Stephen Dixon took the piss out of Conrad along these lines as well. Indeed, slagging off Conrad seems to be a common trait among many of my literary Bohemian heroes. And I do need to heed them. I feel and trust their instincts. It’s almost as if we’re told that we should simply accept that Conrad is a great writer who changed the course of literature (and he did) even as we pretend that he isn’t ancient and hoary and horribly regressive. When I confessed my reluctance to reread Heart of Darkness to a few friends, they told me, “Well, it’s only a hundred pages.” Which suggested very strongly that nobody really wants to read Conrad anymore. He doesn’t pop out at you like Joyce or Faulkner or Nabokov or even Lawrence. And, to tell you the truth, I would much rather reread

It can’t be an accident that the wildly underrated Julian MacLaren-Ross skewered the idea of reading Conrad as an upwardly mobile class aspiration in Of Love and Hunger. In Frog, Stephen Dixon took the piss out of Conrad along these lines as well. Indeed, slagging off Conrad seems to be a common trait among many of my literary Bohemian heroes. And I do need to heed them. I feel and trust their instincts. It’s almost as if we’re told that we should simply accept that Conrad is a great writer who changed the course of literature (and he did) even as we pretend that he isn’t ancient and hoary and horribly regressive. When I confessed my reluctance to reread Heart of Darkness to a few friends, they told me, “Well, it’s only a hundred pages.” Which suggested very strongly that nobody really wants to read Conrad anymore. He doesn’t pop out at you like Joyce or Faulkner or Nabokov or even Lawrence. And, to tell you the truth, I would much rather reread

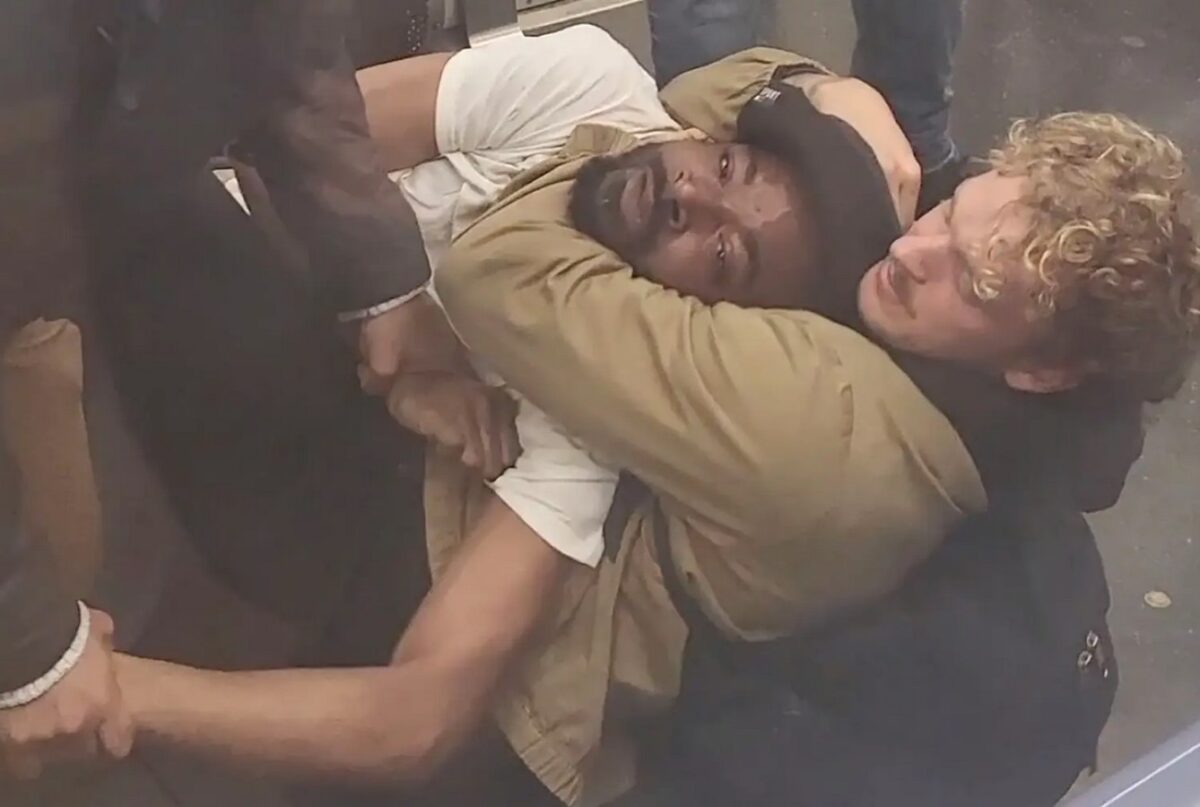

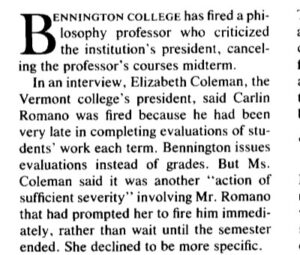

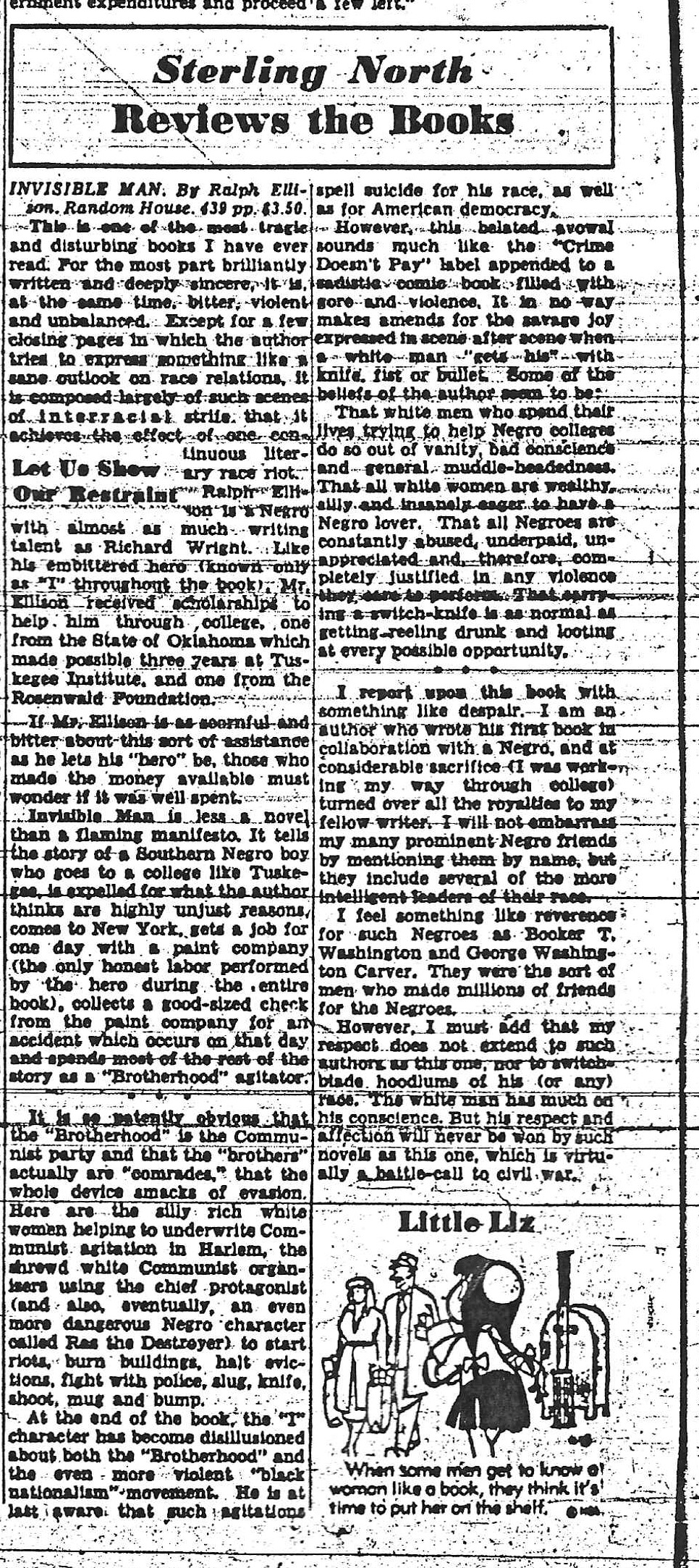

Romano took umbrage with the idea that white gatekeeping “stifles black voices at every level of our industry,” declaring this to be “absolute nonsense.” Never mind that

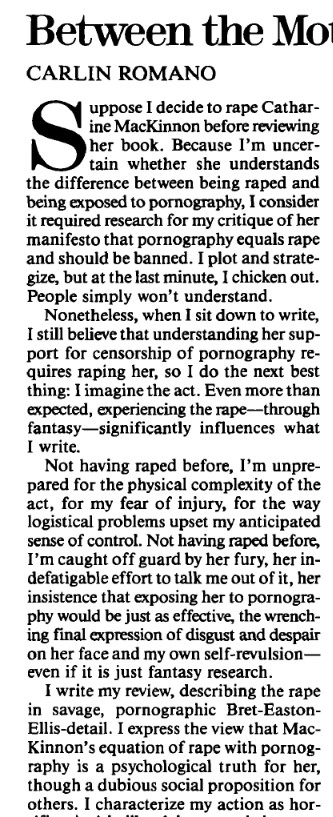

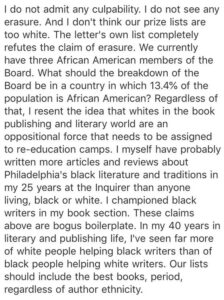

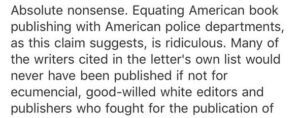

Romano took umbrage with the idea that white gatekeeping “stifles black voices at every level of our industry,” declaring this to be “absolute nonsense.” Never mind that  Romano got even uglier, claiming that black writers would “never have been published if not for ecumenical, good-willed white editors and publishers who fought for the publication of black writers.” Amber Books? Black Classics Press? Third World Press? Triple Crown Publications? Life Changing Books? Any of the far too few African-American publishers who have stepped up to redress the systemic racism that the largely white-owned publishing industry has failed to remedy? That Romano applies “ecumenical” to his atavistic statement says much about his condescending views of writers of color. Apparently, in his view, any publisher who puts out a worthy novel that happens to be written by an African-American is an act of charity rather than an act of merit. James Baldwin? Toni Morrison? Octavia Butler? Ta-Nehisi Coates? Well, you’re lucky that your ass got through the door because Whitey decided to let one or two of you through the gates. Does Romano’s repugnantly racist sentiment here not reinforce the problems of white gatekeeping and not buttress the need for any and all literary organizations to be more inclusive? As far as Romano was concerned, the fact that countless people of color had to fight to be published — despite the fact that African-American novels have continued to be financially successful (Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren sold one million copies, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple sold five million copies, even Ann Petry’s The Street selling one million copies in 1946, the list goes on) — did not get in the way of his sentiment that black people needed to be fawning and grateful, much in the manner of slaves, to white publishers. Romano doubled down on this racism by writing, “In my 40 years in literary and publishing life, I’ve seen far more of [sic] white people helping black writers than of people black people helping white writers.” In other words, Romano believes that black people should devote their already disadvantaged positions to spending all their time promoting white writers.

Romano got even uglier, claiming that black writers would “never have been published if not for ecumenical, good-willed white editors and publishers who fought for the publication of black writers.” Amber Books? Black Classics Press? Third World Press? Triple Crown Publications? Life Changing Books? Any of the far too few African-American publishers who have stepped up to redress the systemic racism that the largely white-owned publishing industry has failed to remedy? That Romano applies “ecumenical” to his atavistic statement says much about his condescending views of writers of color. Apparently, in his view, any publisher who puts out a worthy novel that happens to be written by an African-American is an act of charity rather than an act of merit. James Baldwin? Toni Morrison? Octavia Butler? Ta-Nehisi Coates? Well, you’re lucky that your ass got through the door because Whitey decided to let one or two of you through the gates. Does Romano’s repugnantly racist sentiment here not reinforce the problems of white gatekeeping and not buttress the need for any and all literary organizations to be more inclusive? As far as Romano was concerned, the fact that countless people of color had to fight to be published — despite the fact that African-American novels have continued to be financially successful (Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren sold one million copies, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple sold five million copies, even Ann Petry’s The Street selling one million copies in 1946, the list goes on) — did not get in the way of his sentiment that black people needed to be fawning and grateful, much in the manner of slaves, to white publishers. Romano doubled down on this racism by writing, “In my 40 years in literary and publishing life, I’ve seen far more of [sic] white people helping black writers than of people black people helping white writers.” In other words, Romano believes that black people should devote their already disadvantaged positions to spending all their time promoting white writers.  In short, Romano articulated in very clear terms just what he wants the system to be. And his deplorable viewpoint here is no different from an antebellum slaveholder. Romano’s despicable vision is this: White editors serving as gatekeepers. Black authors dancing with joy at the honor of having their neutered visions “represented.” Romano’s statement is, in short, a racist screed against literary merit and inclusiveness. That Romano cannot acknowledge any white bias that has prevented great literature from being published, even as he demands that African-American writers jump up and down over concessions that their white counterparts would never have to face, is nothing less than a pompous white xenophobe revealing his true colors.

In short, Romano articulated in very clear terms just what he wants the system to be. And his deplorable viewpoint here is no different from an antebellum slaveholder. Romano’s despicable vision is this: White editors serving as gatekeepers. Black authors dancing with joy at the honor of having their neutered visions “represented.” Romano’s statement is, in short, a racist screed against literary merit and inclusiveness. That Romano cannot acknowledge any white bias that has prevented great literature from being published, even as he demands that African-American writers jump up and down over concessions that their white counterparts would never have to face, is nothing less than a pompous white xenophobe revealing his true colors.

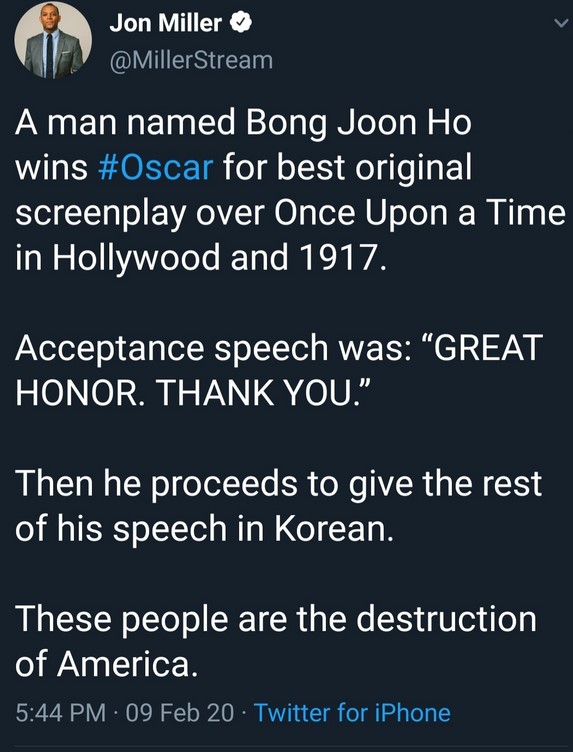

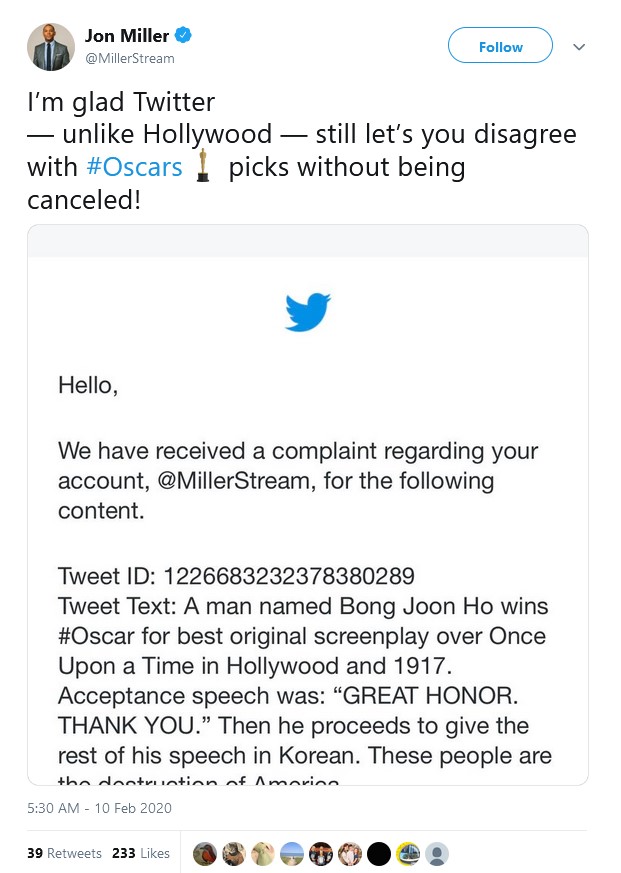

A man with a blue checkmark by the name of Jon Miller, a conservative “White House correspondent for BlazeTV,” tweeted an insulting, cruelly disparaging, and racist message mocking the great filmmaker Bong Joon-ho after he delivered one of his Oscar speeches in Korean. Miller’s disturbingly xenophobic words, which are still published on Twitter as of Monday morning, proceeded to claim that “these people are the destruction of America.” This is language that echoes anti-Semitism in 1930s Germany and

A man with a blue checkmark by the name of Jon Miller, a conservative “White House correspondent for BlazeTV,” tweeted an insulting, cruelly disparaging, and racist message mocking the great filmmaker Bong Joon-ho after he delivered one of his Oscar speeches in Korean. Miller’s disturbingly xenophobic words, which are still published on Twitter as of Monday morning, proceeded to claim that “these people are the destruction of America.” This is language that echoes anti-Semitism in 1930s Germany and

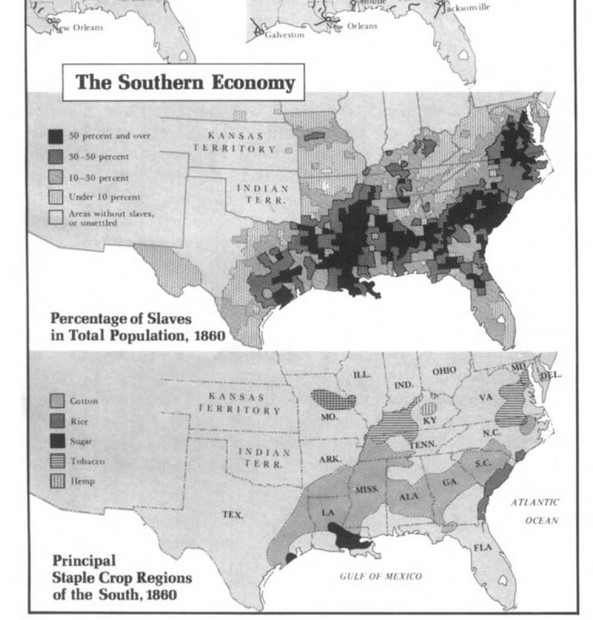

It was a warm day in April when Dr. Martin Luther King was arrested. It was the thirteenth and the most important arrest of his life. King, wearing denim work pants and a gray fatigue shirt, was manacled along with fifty others that afternoon, joining close to a thousand more who had bravely submitted their bodies over many weeks to make a vital point about racial inequality and the unquestionable inhumanity of segregation.

It was a warm day in April when Dr. Martin Luther King was arrested. It was the thirteenth and the most important arrest of his life. King, wearing denim work pants and a gray fatigue shirt, was manacled along with fifty others that afternoon, joining close to a thousand more who had bravely submitted their bodies over many weeks to make a vital point about racial inequality and the unquestionable inhumanity of segregation.

Correspondent: You are careful to write, “Harvard’s importance in eugenics does not imply some nefarious scheme or even a mean-spirited ambiance. Rather, Harvard’s import in this story attests to the scholarly respectability of eugenic ideas at the time.”

Correspondent: You are careful to write, “Harvard’s importance in eugenics does not imply some nefarious scheme or even a mean-spirited ambiance. Rather, Harvard’s import in this story attests to the scholarly respectability of eugenic ideas at the time.”