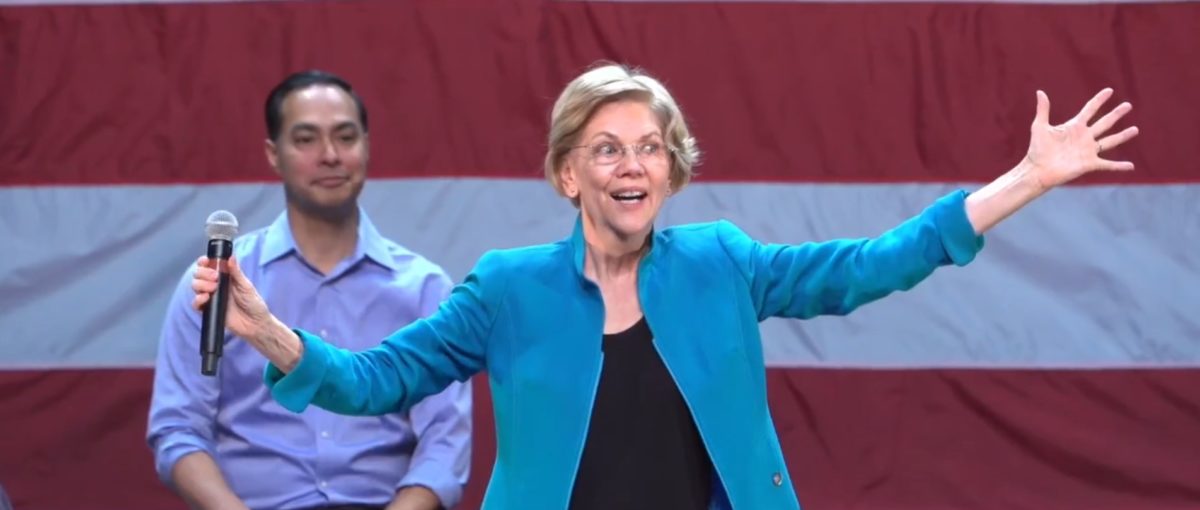

One would need a heart of anthracite to not be wowed by Senator Elizabeth Warren in person. On Tuesday night, at the Kings Theatre in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn — a venue that I was able to walk to from my own stomping grounds, where I am one of a handful of white guys living in a four story building thronged with apartments — Warren was an electric speaker. Wearing a cyan blazer and hitting the stage with the energy of someone at least two decades younger, she filled one of Brooklyn’s finest cathedrals with a series of stump speech talking points in which she discussed her unexpected life decisions — dropping out of a scholarship program to marry her first husband (“Husband #1. It’s never good when you have to number your husbands.”) and why she decided to be a teacher and a professor rather than a lawyer.

One of Warren’s strongest moments was when she described how government could benefit people. She pointed out a time in American life in which toasters would set houses on fire because the toasters would be kept running and a fire emerging from the oven would quickly latch onto an adjacent drape, setting the kitchen and thus the home into a costly conflagration. But when consumer protection laws added an automatic timer to the toasters, the fire problem disappeared. She used this metaphor to segue into her own noble efforts at banking regulation. It was another fine example of how Warren so adeptly connects with smart yet concise everyday comparisons that most Americans understand.

Before this, Julian Castro, who recently abandoned his presidential campaign and seemed to be preparing for a possible role as Warren’s running mate should she get the Democratic nomination, spoke eloquently about the need to include everyone — ranging from those with disabilities to those who are victims of racism and police brutality. And while Castro — dressed in shirtsleeves, relaxed and magnetic on stage — said all the right things, I am not sure if the crowd really understood his full message. I am also not sure if the crowd truly empathized with the two speakers who came before him — whose names I tried to suss out from a Warren volunteer and whose names are tellingly not included on the official Warren website. They were not even included on Warren’s live Twitter stream. But these two speakers felt real to me because they told tales of losing family members due to callous immigration policies and the risks of staying proudly undocumented. Castro and these two speakers were the real America, the America of the 21st century, the America you need to appeal to if you expect to win a presidential election.

I did not take notes, but you have to understand that I didn’t intend to report on this Warren rally at all. I had stupidly believed that the Warren crowd would be a motley group from all walks of life. But on Tuesday night, I was feeling increasingly uncomfortable by how Caucasian and affluent and neoliberal the whole affair was. Despite the fact that one audience member tried to heckle Warren by getting her to badmouth Mayor Pete (to her credit, she didn’t take the bait), the tone was more of a Buttigieg rally rather than a Warren one. The audience was largely white and upper middle-class — a veritable sea of Wonder Bread and Stuff White People Like that unsettled me. As I joked to a friend by text, “This rally is so white that I feel like Ving Rhames.” The volunteers were white. They used ancient cornball slang like “Ditto!” without irony. Was I in Brooklyn Heights or Flatbush? As I stood in line, these people talked of vacationing in France and of the stress of getting out of bed at 2:30 PM and they did not appear to recognize their privilege. I was able to bite my tongue, but I must confess that it rankled me to say nothing. There were complaints among the Warren faithful against Bernie Sanders, about how he was “too mean” and “not nice.” But nothing was said about his policy. Maybe they secretly understood that Sanders is the leading candidate among black millennials and that this is going to be trouble for Warren. The overwhelming takeaway I had was that these white Warren supporters were utterly clueless about how much of a disconnect they had to anyone who isn’t white. I was certain that few of them had ever been poor in their lives.

I watched two African American women try to get into the Kings Theatre, but who were denied entry into the theatre because the Warren volunteers overlooked them in the line and didn’t give them the requisite green sticker that secured them entry. It seemed to me a form of racial profiling. I watched white people refuse to leave tips for the black bartenders who were servicing them. (I dropped a Lincoln into the tip bucket because this upset me.) The first people to leave midway through Warren’s speech who weren’t parents trying to quiet down their kids were African-American. I watched one woman throw up her hands as Warren spoke. And this bothered me. I am sure that this is not the message that Warren wishes to promulgate.

Maybe what I’m trying to identify here is a specific risk-averse form of whiteness. A peculiar timidity that is out of step with these turbulent times and that is certainly contradictory with Warren’s ongoing chant, “I will fight for you!” Just before the rally began, my phone pinged with distressing news of Iran pummeling the Al Asad airbase, which houses American soldiers, with missiles. It was clear retaliation for the American assassination of Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani. It was, by any objective assessment, the beginning of a major international conflict — possibly a protracted war. Castro and Warren, to their credit, acknowledged this at the beginning of their respective speeches. But I brought this up with the white people who attended the rally, thinking that they would share the same horror for unnecessary bloodshed that I did. I was told to shut up and to not bring this up. Because whiteness is blind and selective about the big issues. Not just with the rich inner lives of people who aren’t white, but with cataclysmic events that produce violence and for which privilege insulates white people.

Then it really hit me. The Kings Theatre was in my neighborhood, which I love with all my heart. According to the 2010 census, only one fifth of Flatbush is white. The average household income here is $56,599, which doesn’t buy you a lot of cheddar in New York but that allows one a modestly happy existence. I recognize my own privilege, but I do not consider myself superior to anyone and I spend much of my time listening to other people’s stories. After all, the whole point of life is to always consider perspectives that are not your own. Who the hell am I to declare my life better? That isn’t what democracy is about.

Please understand that I have the utmost respect for Elizabeth Warren and I think she would make a fine President. But it’s her supporters that have spawned these sentiments. I truly believe they don’t get it. They are simply more sedate versions of the “Bernie bro” stereotype that they have spent the last three years kvetching about. But Bernie spent the last four years learning from his mistakes and trying out an approach that was more inclusive. Warren’s white volunteer base does not seem to understand that you can’t win the 2020 presidential election if you lack the ability to appeal to people who are not white. If you want to do affluent white people things on your own time, such as blowing $180 on a Sunday Funday brunch and complaining about how hard it is to have it all, that’s fine. I’m not going to begrudge you for it. But don’t think for a second that your multicultural myopia will guarantee you an election victory. If you can’t be bothered to remember the names of people who aren’t white and who are genuinely brave and who have truly lived — and, again, I am guilty on this front with the two speakers and I will do better next time — then you have no business participating in presidential politics.

The upshot is that I do not believe Elizabeth Warren can win because the white people who volunteer for her campaign cannot listen. They not only refuse to recognize their privilege, but, if my experience on my own home turf is any indication of a possibly larger national problem, they refuse to do so. Bernie, by contrast, has found support among Muslims and many other groups that the Warren volunteer clan will not talk to because, as nimbly documented by BuzzFeed‘s Ruby Cramer, he has adopted a strategy of presenting stories that represent struggles.

“PEOPLE FIRST” read the letters held by the premium volunteers allowed to sit on stage. But are they really committed to people? Or are they being selective about it?

Elizabeth Warren knew the right neighborhood to go to. But she cannot win because, for all of her dazzling prowess and her willingness to take selfies with anyone who shows up, she cannot reflect the diversity of that neighborhood. And if her present logistical base gets a vital neighborhood in Brooklyn so unabashedly wrong, how can we expect her to appeal to the gloriously variegated possibilities of America?