(This is the twenty-seventh entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: Scoop.)

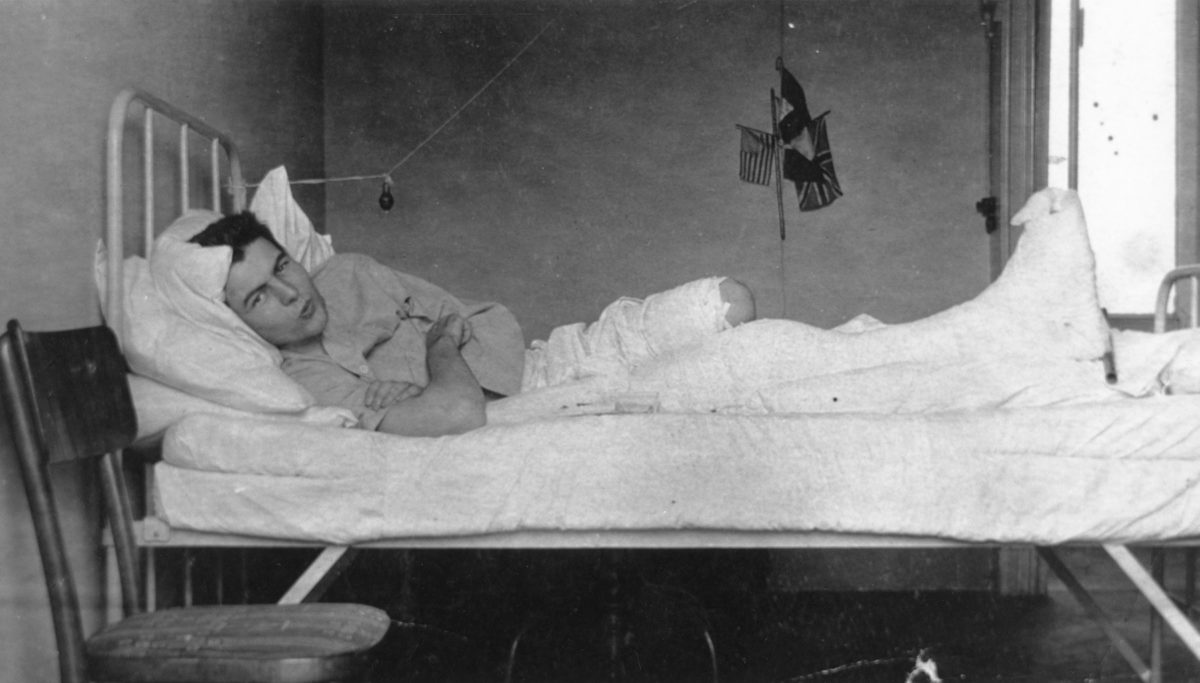

You likely know the basics: An American goes to Italy and enlists as a “tenente.” He drives a battlefield ambulance just before his nation enters World War I. He gets wounded. He meets a nurse at a hospital. He falls in love. He feels free as he recovers. He feels trapped as he returns to the front. He gets disillusioned. He flees. He finds her again. Bad things happen. But A Farewell to Arms is so much more than this. It is a heartbreaking love story. It is a remarkably subtle indictment of war. It shows how people bury their romantic longings behind duty and how there’s a greater bravery in fulfilling what you owe to your heart. It argues for life and love. Its final paragraph is devastating. It zooms along with masterly prose that is buried with treasure. It is one of the greatest novels of the early 20th century. This statement is not hyperbole.

You likely know the basics: An American goes to Italy and enlists as a “tenente.” He drives a battlefield ambulance just before his nation enters World War I. He gets wounded. He meets a nurse at a hospital. He falls in love. He feels free as he recovers. He feels trapped as he returns to the front. He gets disillusioned. He flees. He finds her again. Bad things happen. But A Farewell to Arms is so much more than this. It is a heartbreaking love story. It is a remarkably subtle indictment of war. It shows how people bury their romantic longings behind duty and how there’s a greater bravery in fulfilling what you owe to your heart. It argues for life and love. Its final paragraph is devastating. It zooms along with masterly prose that is buried with treasure. It is one of the greatest novels of the early 20th century. This statement is not hyperbole.

It is now quite fashionable to bash Hemingway rather than praise him, as the flip Paul Levy recently did in his oh so hip and not very bright “hot take”: “The Hemingway corpus is full of artistic failure.” Well, sure it is. I’ve read it all three times at different periods in my life and I don’t think any honest reader would deny that. When I was an obnoxious punk in my twenties, I resisted Hem big time, feeling that he could not teach me to be a man in the way that James Baldwin and F. Scott Fitzgerald had, yet I somehow held onto his books, sensing that I could be colossally wrong. (I was.) Even today, I have to acknowledge that To Have and Have Not is an embarrassment. The Garden of Eden is an interesting but unconsummated train wreck. For Whom the Bell Tolls has its moments, but the Old English verbs and the lack of subtlety can be risible. I’ve never quite been able to leap into The Old Man and the Sea, but that says more about me than Hem. The upshot is that there are quite a few clunkers in Hem’s collected works and some of the Nick Adams tales ain’t all that, but one could make this claim about any author. In the end, when you have a masterpiece like A Farewell to Arms that never grows tedious no matter how many times you reread it, who in the hell cares about the misses? There’s no profit in calculating a shallow statement when the crown jewels shine bright in your face.

The other way that people ding Hem these days is by singling out his macho posturing or peering at his pages through the prism of unbridled masculine hubris. The naysayers dismiss Lady Brett Astley in The Sun Also Rises as an archetype without recognizing her enigma or the way she aptly epitomized the Lost Generation. They don’t acknowledge how Hem had to prostrate himself before Beryl Markham in a letter to Maxwell Perkins and that he did get on (for a time) with Martha Gellhorn, who neither suffered fools nor caved to condescension.

Yet there is certainly something to Hemingway’s women problem, especially as seen in the correspondence between Fitzgerald and Hemingway. In June 1929, F. Scott Fitzgerald sent Hem a letter and observed how, in his early work, “you were really listening to women — here you’re only listening to yourself, to your own mind beating out facily a sort of sense that isn’t really interesting.” (Hemingway’s reply: “Kiss my ass.”)

Scott’s warning remains a very shrewd assessment on what’s so fascinating and frustrating about Hemingway. I’d argue that one of the best ways to ken Hem is to recognize that he was a wildly accomplished giant when he placed his own ego last and that any transgressions that today’s readers detect only emerged when Hem became overly absorbed in his own self. And on this point, one can find a strange sympathy for the man, thanks in part to Andrew Farah’s recent biography, Hemingway’s Brain, which points to Ernest’s many head injuries (which included nine concussions) and concludes that he suffered from CTE, the brain disease seen in professional football players after too many years of violent tackles. This theory, which takes into account the decline of Hemingway’s handwriting in his latter years, would also offer an explanation for the wildly disparate writing quality and thus invalidates Mr. Levy’s foolish pronouncement.

The world breaks every one and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

A Farewell to Arms thankfully places us shortly after the rising sun of Hem’s career and, like its predecessor, the book contains razor-sharp prose, keen observations (ranging from Umberto Notani’s infamous The Black Pig, trains packed with soldiers, and the repugnant wartime indignity of a hopped up tyrant fiercely questioning a man who is fated to be shot), and a beautiful epitomization of the famous “iceberg theory” that Hemingway posited in Death in the Afternoon:

If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. A writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing.

Much has been spilled over Hemingway’s declarative sentences, which are beautifully honed in this masterpiece. (Hem wrote 47 versions of the ending.) But I’d like to single out “was,” the most frequently used word in this novel. On a surface level, “was” is the most expedient way to hurl us into Frederic’s world: a simple verb of action and hard deets, but one that likewise deflects interior thought. It’s easy to dis Hem as a man’s man summing up life and the earth and the grit and all else that makes us want to ape him even though there can be only one, but the key to seeing the beauty of “was” is knowing that this book is all about pursuing a lost and deeply moving romantic vision, one kept carefully hidden from the beginning. Style advances the perspective and keeps us curious and lets us in and “was” is the way Hem gets us there.

Hemingway uses language with extraordinary command to clue us in on the distinct possibility that this story is in some sense a dream — indeed, a dream involving death based on what Hem was never able to make with the nurse Agnes von Kurowsky while holed up in a ward. There’s the makeshift hospital office, with its “many marble busts on painted wooden pillars,” which is further compared to a cemetery. In the novel’s first part, there are very few adverbs — save “winefully” early on and “evidently” and “directly” in the same sentence as guns rupture Frederic’s existence. The first rare simile (“seeing it all ahead like moves in a chess game”) occurs when Frederic first tries to kiss Catherine and is greeted with a slap (which Catherine apologizes for). This is a far cry indeed from what The Daily Beast‘s Allen Barra recently claimed, without citing a single example, as “flowery and overwritten.” A Farewell to Arms basks in the same beautiful realm between the real and the ethereal that The Great Gatsby does, albeit in a different landscape altogether, but it offers enough ambiguity to speculate about the characters while encouraging numerous rereads.

Language also carries the deep resonances of what people mean to each other. Catherine cannot stand a triple-wounded vet named Ettore and repeats “dreadful” twice and “bore” four times when she vents to Frederic. The words “She won’t die” are also repeated in one harrowing paragraph near the end. (Indeed, if you see a word or a phrase repeated in Hemingway’s fiction, there’s a good chance that something bad will happen.) Shortly after Frederic is moved to the freshly built hospital in Milan (itself a marvelous metaphor for the fresh start of Frederic’s blossoming love for Catherine), he takes to Dr. Valentini, who speaks in a series of short sentences over the course of a paragraph (a small sample: “A fine blonde like she is. That’s fine. That’s all right. What a lovely girl.”) and who Frederic later calls “grand.” The syntax, chopped and sheared and housed within manageable units, represents a telegraph from the human heart like no other.

Frederic acknowledges that he lies to Catherine when he tells her that she’s the first woman he’s loved. Now it’s tempting to roll your eyes over the “I’ll be a good girl” business that often comes from Catherine, but it’s also a safe bet to speculate that Frederic is likewise lying about what Catherine has actually told him, much as Hem himself has fudged the full extent of his “affair” with Agnes von Kurowsky through fiction. (“Now, Ernest Hemingway has a case on me, or thinks he has,” wrote von Kurowsky in her diary on August 25, 1918. “He is a dear boy & so cute about it.”)

An enduring romance is often built on a pack of lies. We often fail to recognize the full totality of who a lover was until we are well outside of the relationship. As for friendship, I’d like to argue that Miss Gage is a fascinating side character who stands up for this. She’s someone who ribs Frederic about not fully understanding what friendship is. Later, when Frederic returns to the front lines, Rinaldi tells him, “I don’t want to be your friend. I am your friend.” And if Frederic can’t recognize friendship, does he really know how to read the room when Cupid shows up with a puckish smile? Hem’s subtle acknowledgment of these basic truths allows us to trust and become invested in Frederic’s voice. And I’d like to think that even Hem’s opponents could get behind such idyllic imagery as Frederic and Catherine “putting thoughts in the other one’s head while we were in different rooms” or agreeing to sneak off to Switzerland together or even the funny “winter sport” business with customs. These are endearing and beautiful romantic moments that certainly show that Hem is far more than a repugnant hulk.

Love is a high stakes game, but it’s always a game worth playing. If you beat the odds, the payout is incalculable. Small wonder that the happy couple ends up throwing their lire into a rigged horse race. Indeed, Frederic’s early days with Catherine are a game like bridge where “you had to pretend you were playing for money or playing for some stakes.” For all of Frederic’s apparent confidence in not knowing the stakes, he does not reveal his name for a while — on its first mention, Frederic only partially spills his name as he is drinking. He is also more taken with the allure of being alone — as seen later in a Donnean nod when he says that “[w]hat made [Ireland] pretty was that it sounded like Island.” His loneliness is further cemented when Miss Ferguson says that Catherine cannot see him.

Is this the loneliness of war? We learn later that Frederic came to Rome to be an architect, although this is likely a lie, given that it is repeated a second time to a customs officer. But it does suggest that Frederic cannot build his own life without another. Perhaps this is the solitude that comes from the relentless pursuit of manly vigor (boxing, bullfighting, hunting) that Hemingway was to explore throughout his life? There is one clue late in the book when Hemingway writes, “The war seemed as far away as the football game of someone else’s college,” and another midway through when Frederic wonders if major league baseball will be shut down if America entered the war. (Fun fact: There was indeed a World War I deadline put into place, but the two leagues squeezed in numerous doubleheaders to ensure that the season could play out.) If the First World War arose in part because humanity was involved in a vicious game, then Hemingway seems to be suggesting that further games rooted in play and peace must be promulgated to restore the human condition. Frederic cynically quips to the 94-year-old Count Greffi, “No, that is the great fallacy; the wisdom of old men. They do not grow wise. They grow careful.” But if being careful is the true measure of existence, why then do we celebrate valor that often emerges from reckless circumstances? Indeed, Hemingway sends up the very nature of heroism up when Frederic wakes up in the hospital and is greeted by Rinaldi, who presses him to confess the specific act he committed to earn his medal. “No,” replies Frederic. “I was blown up while we were eating cheese.”

In an age where razor blade ads are urging us to question what manhood should represent, there’s something to be said about studying what’s contained within masculinity’s ostensible ur-texts and with how careful men are in saying nothing but everything. A Farewell to Arms is a far more sophisticated and deeply beautiful novel when you start examining its sentences and questioning its motivations. Caught in a mire between love and war, Frederic opts for the laconic rather than the prolix. And in doing so, he tells us far more about what it means to love and lose than most authors can convey in a lifetime.

Next Up: Nathanael West’s Day of the Locust!

Merchant Ivory Productions has been one of the greatest threats to literature during the past three decades. Known for producing well photographed films that put most sane people to sleep, the Merchant Ivory team has demonstrated a remarkable knack for divesting zest from the literary classics. They have ordered esteemed actors across sweeping vistas as if they are unbudgeable bovine who require vast encouragement to produce milk. They have bored more often than seems reasonable. Where Orson Welles’s Shakespeare adaptations or Iain Softley’s The Wings of the Dove or Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon or Sally Potter’s Orlando or William Wyler’s The Heiress or Corman’s Poe pictures or The Royal Shakespeare Company’s nine hour version of Nicholas Nickleby bristle with life and visual excitement, demanding that you get your hands on the source material at once, the Merchant Ivory movies are the cinematic equivalent to visiting the in-laws or steeling yourself up for a dreadful Thanksgiving or attending a funeral for someone you didn’t really know that well.

Merchant Ivory Productions has been one of the greatest threats to literature during the past three decades. Known for producing well photographed films that put most sane people to sleep, the Merchant Ivory team has demonstrated a remarkable knack for divesting zest from the literary classics. They have ordered esteemed actors across sweeping vistas as if they are unbudgeable bovine who require vast encouragement to produce milk. They have bored more often than seems reasonable. Where Orson Welles’s Shakespeare adaptations or Iain Softley’s The Wings of the Dove or Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon or Sally Potter’s Orlando or William Wyler’s The Heiress or Corman’s Poe pictures or The Royal Shakespeare Company’s nine hour version of Nicholas Nickleby bristle with life and visual excitement, demanding that you get your hands on the source material at once, the Merchant Ivory movies are the cinematic equivalent to visiting the in-laws or steeling yourself up for a dreadful Thanksgiving or attending a funeral for someone you didn’t really know that well.