(This is the forty-first entry in The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: Death Comes for the Archbishop.)

There are many go-nowhere men like Walker Percy’s Jack “Binx” Bolling in American life: the type who creates nothing and who lives like some vaguely seedy salesman overly concerned with easy comities and sartorial aesthetics, the quasi-urbane man who, at his worst, is so terrified of even remotely staining his choppers that he slurps nothing but colorless sugar-free smoothies for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I can’t say that I’ve wanted to spend a day (much less a life) like this. I am too much of a creative, feverishly curious, and pro-active man with a formidable work ethic and a great brio for life (and all of its attendant messes) to do so, but I do have my moments when I feel the draw to lie in bed for hours and listen to the beautiful rap of rain against my window pane, which is certainly a more human pastime than sucking on the cheap glass teats of television and being extremely online. Then I come to my senses and realize that I do need to make something that day, with the fulsome freedom of not needing approbation, so that I can sleep better at night and feel some self-respect — a drive for independence and authenticity that is decreasingly shared by my fellow Americans as the apocalyptic headlines lull many formidable workhorses into permanent or partial fatigue. I don’t blame anyone for slumming it. This is an exhausting asceticism for anyone to practice and the prolificity that results from my febrile commitment is probably one reason why some people fear me.

There are many go-nowhere men like Walker Percy’s Jack “Binx” Bolling in American life: the type who creates nothing and who lives like some vaguely seedy salesman overly concerned with easy comities and sartorial aesthetics, the quasi-urbane man who, at his worst, is so terrified of even remotely staining his choppers that he slurps nothing but colorless sugar-free smoothies for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I can’t say that I’ve wanted to spend a day (much less a life) like this. I am too much of a creative, feverishly curious, and pro-active man with a formidable work ethic and a great brio for life (and all of its attendant messes) to do so, but I do have my moments when I feel the draw to lie in bed for hours and listen to the beautiful rap of rain against my window pane, which is certainly a more human pastime than sucking on the cheap glass teats of television and being extremely online. Then I come to my senses and realize that I do need to make something that day, with the fulsome freedom of not needing approbation, so that I can sleep better at night and feel some self-respect — a drive for independence and authenticity that is decreasingly shared by my fellow Americans as the apocalyptic headlines lull many formidable workhorses into permanent or partial fatigue. I don’t blame anyone for slumming it. This is an exhausting asceticism for anyone to practice and the prolificity that results from my febrile commitment is probably one reason why some people fear me.

But poor Binx Bolling has nothing like that, which is why I find him so interesting and why I find Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer to be more weirdly meaningful with each fresh reeread. Absent of any real purpose, Bolling spends much of this plotless novel trying to shoehorn his rudderless life into something, particularly a “search,” which is not really a search for anything. He seems unwilling to ride or die with unconscious instinct, with the sheer enjoyment of being alive. (Typical of Bolling, he has no allegiance. At one point, he even declares himself “Jewish by instinct.”) He recognizes that instinct is something that people possess, but that doesn’t seem enough for him:

At the great moments of life — success, failure, marriage, death— our kind of folks have always possessed a native instinct for behavior, a natural piety or grace, I don’t mind calling it. Whatever else we did or failed to do, we always had that. I’ll make you a little confession. I am not ashamed to use the word class. I will also plead guilty to another charge. The charge is that people belonging to my class think they’re better than other people. You’re damn right we’re better. We’re better because we do not shirk our obligations either to ourselves or to others. We do not whine. We do not organize a minority group and blackmail the government. We do not prize mediocrity for mediocrity’s sake…Our civilization has achieved a distinction of sorts. It will be remembered not for its technology nor even its wars but for its novel ethos. Ours is the only civilization in history which has enshrined mediocrity as its national ideal.

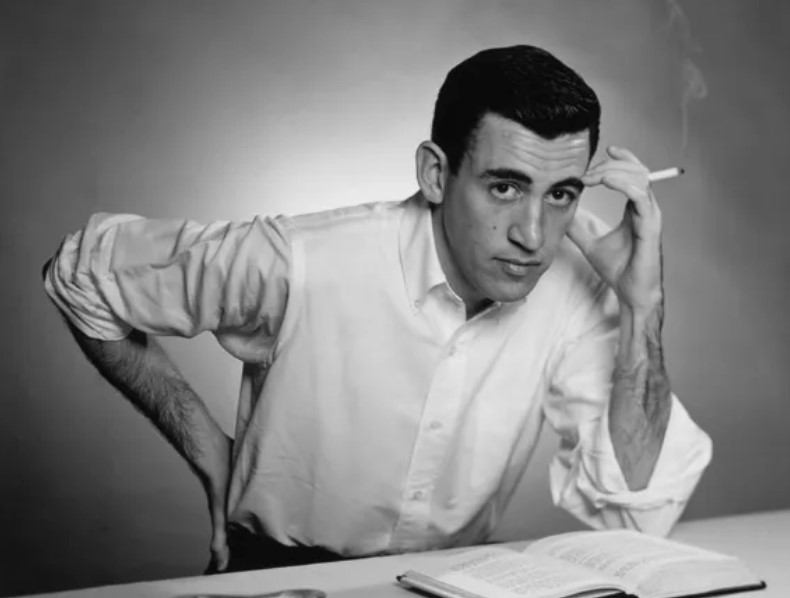

But is this really so “better”? This is fairly similar to Holden Caulfield’s insufferable kvetching, except that it is far more fascinating because Bolling, unlike Caulfield, is more actively self-aware and constantly observant of others. He chooses to think and feel this way. It is what I call the “fuck my life” look that you see on people’s faces after they have given up on any dreams after the age of forty.

While the Binx Bollings of our world are capable of a few spontaneous decisions and may possess some cultural tastes and perhaps a soupçon of passion, they differ from the “slacker” types that Richard Linklater rightfully celebrated in his wonderful 1991 film in that exuberance is often absent and there isn’t an unusual nobility or even an ethos to their indolence. (And I would contend that Bollling’s “novel ethos” is a false one. For he says this when he has nothing in particular he is striving for. And those who strive for something rarely have a mediocre ideal in mind.)

The Binx Bollings simply live and that’s about it. They are, in short, working stiffs and the burden of surviving is often too much to do much more than that. You’ll find them represented in varying shades within Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road, Richard Ford’s Frank Bascombe books, John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces, Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes, John P. Marquand’s The Late George Apley, Sam Lipsyte’s Homeland, Richard Russo’s Nobody’s Fool, Stewart O’Nan’s Last Night at the Lobster, and John Williams’s Stoner. And while I have no desire to leave out women in my literary consideration, yes, the fear of becoming “mediocre” or “detached” like this — the natural “evolution” of Dostoevsky’s “Underground Man” or what Colin Wilson unpacked in The Outsider — does seem to be an overwhelmingly male concern. Contemporary novelists as brilliant as Adelle Waldman, Kate Christensen, and Lauren Groff (you should very much read their work too) have also tackled this to great effect, although they are usually more interested in effect rather than cause or state and the vicarious first-person experience is of less importance. Think of the way that the characters in Edith Wharton, Muriel Spark, and Iris Murdoch (all literary queens who I will enthuse about to my dying day!) are so much more alive than the Binx Bolling type. I also can’t help but think of the way Ross McElwee (also a man of the South) brilliantly and vulnerably put himself front and center in such a way with his fascinating series of personal documentaries. Updike, in particular, was one of the foremost literary Johns drawn to these men and he nimbly spoke to American readers who recognized the telltale cadences of Durkheimian anomie.

Which is not to negate the quotidian struggles of the Binx Bollings. The miracle of Percy’s novel is that we’re still with him on his journey despite all this. Still, it often never occurs to these types to pay attention to the “beloved father” or “husband of X” found so ubiquitously on tombstones, which matters so much more than the roll of a Taylorist scroll memorializing an endless concatenation of checked off tasks. The worst of these aimless men possess no sense of humor and somehow transform into a homely insectoid creature worse than anything that ever bolted upward from Kafka’s imagination, a listless monstrosity commonly referred to as a “critic.” The critic, who is often a cretin, is a pitiful and unsmiling quadraped incapable of expressing joy, much less stridulating his legs together to make a pleasant sound in springtime.

And while we’re on the subject of bugs, as it so happens, there is a cameo appearance from a coterie of creepy-crawlies in Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer that saunter right past our malaise-fueled man Binx: “They dive and utter their thrumming skonk-skonk and go sculling up into the bright upper air.” Percy’s emphasis on sounds and gerunds here really says it all. That same whirlydirsh language is often beyond poor Binx.

The source for Boiling — as well as Williston Barrett, a Percy protagonist who would be explored in two stages of life (youthful folly and middle age) in, respectively, The Last Gentleman and The Second Coming) — was Percy’s essay “The Man on the Train” (collected in The Message in the Bottle) — in which Percy firmly established the type of protagonist he was interested in writing about:

There is no such thing, strictly speaking, as a literature of alienation. In the re-presenting of alienation the category is reserved and becomes something entirely different. There is a great deal of difference between an alienated commuter riding a train and this same commuter reading a book about an alienated commuter riding a train….The nonreading commuter exists in true alienation, which is unspeakable; the reading commuter rejoices in the speakability of his alienation and in the new triple alliance of himself, the alienated character, and the author. His mood is affirmatory and glad: Yes! that is how it is! — which is an aesthetic reversal of alienation.

In other words, Percy could not bring himself to write about a character in unbearable despair (it is not an artistic focus for the faint of heart) — largely because his natural writing voice is driven by a fine comedic impetus, with the Catholic novelist’s concern for philosophy planting one foot in the wings and the other on stage. (Look no further than Antonia White, Gene Wolfe, and Graham Greene for similarly intriguing juxtapositions.) Much like Richard Linklater’s “slacker” archetype, Percy seeks to pursue the bare minimum of alienation, although, as can be seen with Dr. Thomas More in Love in the Ruins, Percy’s characters are more eggs-in-one-basket types (in More’s case, the Ontological Lapsometer that he sees as a decaying society’s cure-all) and less committed to the free-floating spontaneity of hitching a ride with strangers, taking the entire day to assemble an elaborate rock structure to represent femininity, or being interviewed for a film student’s documentary.

At this point, the gusto-driven reader may rightfully ask, “So why read about this?” For the same reason that we read about any “unlikable” character. This is a form of living, albeit while clutching the bottom of one’s hemp, that is part of the human experience. The eccentric film journalist Jeffrey Wells has recently suggested that the criteria of art (specifically movies) involves being put into “a kind of alternate-reality mescaline dream state.” And while escapism is certainly a dopamine-fueled pastime practiced by a population increasingly hostile to pleasurable cerebration, requiring little of the mind but an uncritical blank slate and a sybarite’s zeal for incessant orgasm, what of the wisdom picked up from raw human experience? Art gives us the advantage of having access to the interior thoughts and feelings of those we may be disinclined to meet in the here and now. Wells’s limited definition therefore nullifies Jonathan Glazer’s excellent film adaptation of Martin Amis’s novel, The Zone of Interest, which is nothing less than a vital and deeply horrifying atmospheric experience warning us of the shockingly pedestrian character of fascism, which is dangerously close to permanently destroying the very fabric of this bountiful nation should the Orange Menace emerge victorious in November.

Likewise, Walker Percy’s masterpiece is a similar (if less baleful) cautionary tale of what it means to coast and how commitment to something (or, in Bolling’s case, someone) represents the inevitable reckoning that anyone is fated to face at one point or another. It is a sneaky warning to anyone with true fuck-it-all drive that even the dreamer faces the risk of slipping into adamantine complacency and is ill-equipped to gently pluck a rose from the carefully maintained bush planted atop a Sisyphean alp.

The New Yorker‘s Paul Elie has smartly observed that The Moviegoer is curiously ahistorical: less taken with unpacking the neverending residue of the Civil War, racial tension, or other hallmarks found prodigiously within typical Southern fiction. The novel is also, by its own prefatory admission, an inexact version of New Orleans: far from meticulously recreated like Joyce’s Dublin, though not entirely fabulist.

But I do think Elie is a tad too dismissive of Southern inventiveness to suggest that Percy mined exclusively from the European existentialists to summon his vision of the unlived and shakily examined life — even though the debt to Kierkegaard is obvious in The Moviegoer (and in “The Man on the Train”), not just because of the opening epigraph:

As for my search, I have not the inclination to say much on the subject. For one thing, I have not the authority, as the great Danish philosopher declared, to speak of such matters in any way other than the edifying. For another thing, it is not open to me even to be edifying, since the time is later than his, much too late to edify or do much of anything except plant a foot in the right place as opportunity presents itself – if indeed asskicking is properly distinguished from edification.

But what is this search? I strongly recommend Rose Engler’s smart unpacking, which eloquently outlines the religious component that was dear to Percy, but there is something intriguingly postmodern about it. One of Percy’s early reviewers — Edwin Kennebeck in Commonweal — believed that The Moviegoer entailed a search not merely for meaning, but for something beyond despair. And there is something to this, given how Bolling categorizes the search early on as “what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life.” The movies that Bolling regularly watches do not present a true search. And, for Bolling, it can be argued that his search involves doing everything possible to avoid that search, even though he knows inherently that he must search. Denied definitive time and space by Percy, Bolling splits up his search into horizontal and vertical ones, framed without any proper construct from Eddington’s The Expanding Universe. He complains of his family not understanding his search. He searches for a starting point by scribbling in a notebook and, after all this “effort,” tells us, “The search has spoiled the pleasure of my tidy and ingenious life in Gentilly.”

Kenneback pinpointed, quite rightly, that Bolling’s decision to marry Kate represented “a search ended and an ordeal begun.” Belonging then, which most of us crave for and which Bolling is not especially good at, represents the cruel gauntlet thrown down by the universe. Bolling tells us, “Show me a nice Jose cheering up an old lady and I’ll show you two people existing in despair.” He believes that Kate sustains a look of being serious, “which is not seriousness at all but despair masquerading as seriousness.”

Perhaps we’re all pretending in one way or another as we saunter about this mortal coil. But the tragedy of Binx Bolling is that, even with his apparent religious conversion, he cannot seem to accept life at face value. But he is not the only one suffering. Kate has this to say:

“Have you ever noticed that only in time of illness or disaster or death are people real? I remember at the time of the wreck — people were so kind and helpful and solid. Everyone pretended that our lives until that moment had been every bit as real as the moment itself and that the future must be real too, when the truth was that our reality had been purchased only by Lyell’s death. In another hour or so we had all faded out again and gone our dim ways.”

If our presence here is indeed ephemeral, should this not provide greater motive to connect and to find joy? The Catholic mind, and thus the Catholic novel, is not without its involutions and contradictions.

Next Up: Max Beerbohm’s Zuleika Dobson!

Like many semi-literate members of my generation, I first read The Catcher in the Rye at the age of fifteen, following the ethereal rites and cadences of older kids turned on by the same seductive anthem to nonconformity. At that angsty teenage time in my life, Holden Caulfield appealed to my rebellious and anti-authoritarian streak. This reaction, in and of itself, is not especially unusual. Salinger has continued to be assigned to high school English curricula in large part because you can inveigle kids into reading by making the titles forbidden. (Witness how Art Spiegelman’s Maus

Like many semi-literate members of my generation, I first read The Catcher in the Rye at the age of fifteen, following the ethereal rites and cadences of older kids turned on by the same seductive anthem to nonconformity. At that angsty teenage time in my life, Holden Caulfield appealed to my rebellious and anti-authoritarian streak. This reaction, in and of itself, is not especially unusual. Salinger has continued to be assigned to high school English curricula in large part because you can inveigle kids into reading by making the titles forbidden. (Witness how Art Spiegelman’s Maus

William Somerset Maugham was a largely gloomy man who just wanted to be loved. And because Maugaham was constitutionally incapable of behaving in the manner of Sally Field accepting her Oscar (and was frequently self-deprecatory), he often wasn’t. It certainly did not help that he was closeted, emo as fuck, fiercely protective of his private life, tight-lipped about his inexorable agony, and reported by many of his acquaintances and admirers as emotionally detached (although he did commit many quiet acts of generosity, including building up a library at The King’s School in Canterbury, where the ashes of Ashenden’s creator were eventually scattered). He frequently quipped that he stood in the first row of second-rate writers, almost to steel himself against the effusive and well-deserved reception he received for his considerable literary accomplishments. The Moon and Sixpence, Cakes and Ale, and The Painted Veil remain remarkably vivacious and salacious for their time and are still eminently readable today.

William Somerset Maugham was a largely gloomy man who just wanted to be loved. And because Maugaham was constitutionally incapable of behaving in the manner of Sally Field accepting her Oscar (and was frequently self-deprecatory), he often wasn’t. It certainly did not help that he was closeted, emo as fuck, fiercely protective of his private life, tight-lipped about his inexorable agony, and reported by many of his acquaintances and admirers as emotionally detached (although he did commit many quiet acts of generosity, including building up a library at The King’s School in Canterbury, where the ashes of Ashenden’s creator were eventually scattered). He frequently quipped that he stood in the first row of second-rate writers, almost to steel himself against the effusive and well-deserved reception he received for his considerable literary accomplishments. The Moon and Sixpence, Cakes and Ale, and The Painted Veil remain remarkably vivacious and salacious for their time and are still eminently readable today.

Our universe has become more hopelessly transactional. Vile narcissists with limitless greed and an absence of smarts and empathy have taken over the landscape with their blunt bullhorns. At every socioeconomic level, you will find a plurality of mercenaries who will push any bright and promising head beneath the waterline with ruthless cruelty. Perhaps I’m finally understanding, at an embarrassingly late age, just how commonplace such self-serving treachery is in our world. But what’s the alternative? Cynicism? At times, I have a sense of humor that is darker than the nightscape above the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory, but no thanks. I’ve always been a cautious optimist with a healthy handle on reality, but I still detest this state of affairs. I will still speak out vociferously against it and fight the business-as-usual cowards who uphold this great sham known as the status quo at any personal cost. I stump for the outliers and the misfits. The people who have authentic and vital voices. I don’t care who they are or where they come from. I will stick up for the gas station attendants and the baristas. I will listen to their full stories rather than judge them from a fleeting glance or a superficial and supercilious position. I despise bullies and opportunists. I believe in affording everyone basic dignity. I believe that everyone has it within them to grow and to learn and that inquisitive efforts should never be mocked, especially when genuine curiosity is now in such short supply. Reprobates who use their positions of power to denigrate the marginalized and the underprivileged are scumbags who need to be fought and, if necessary, destroyed.

Our universe has become more hopelessly transactional. Vile narcissists with limitless greed and an absence of smarts and empathy have taken over the landscape with their blunt bullhorns. At every socioeconomic level, you will find a plurality of mercenaries who will push any bright and promising head beneath the waterline with ruthless cruelty. Perhaps I’m finally understanding, at an embarrassingly late age, just how commonplace such self-serving treachery is in our world. But what’s the alternative? Cynicism? At times, I have a sense of humor that is darker than the nightscape above the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory, but no thanks. I’ve always been a cautious optimist with a healthy handle on reality, but I still detest this state of affairs. I will still speak out vociferously against it and fight the business-as-usual cowards who uphold this great sham known as the status quo at any personal cost. I stump for the outliers and the misfits. The people who have authentic and vital voices. I don’t care who they are or where they come from. I will stick up for the gas station attendants and the baristas. I will listen to their full stories rather than judge them from a fleeting glance or a superficial and supercilious position. I despise bullies and opportunists. I believe in affording everyone basic dignity. I believe that everyone has it within them to grow and to learn and that inquisitive efforts should never be mocked, especially when genuine curiosity is now in such short supply. Reprobates who use their positions of power to denigrate the marginalized and the underprivileged are scumbags who need to be fought and, if necessary, destroyed.