Month / May 2006

BEA: More Coming

As C. Max Magee has pointed out, BEA is an exercise in endurance. I am now in the hotel room with twenty minutes to prepare for tonight’s festivities. I have had ten hours of sleep in the past four days. I am speaking in funny voices. More later.

BEA: More Posts to Come

I still have a good deal to approach (we haven’t even hit the events of Thursday night or Friday!), but I again have to hit the floor. But I will say that all of the people I’ve had the pleasure to meet have been nothing less than scintillating. On Thursday, I was privileged to meet Kassia Kroszer, Carolyn Kellogg and the exceptionally sweet Wendi Kaufman (and I got to run into my pals Megan, Lauren, Mark, Sarah and Ron again). On Friday, I ran into Bud Parr again and got to meet Matt Cheney, Gwenda Bond and C. Max Magee for the first time. (Rumor has it that poor Lizzie was accosted by Mr. Segundo last night.)

I also go to chat with Tayari on Thursday night just before she left for her magnificent retreat.

There have been several others, which will have to be inserted into various reports. But perhaps the funniest encounter was with Brigid Hughes, who saw my tag, let loose a great hush of recognition. And then she asked me, “But what are YOU doing here?”

Lady, that’s the question I’ve been asking myself my entire life!

BEA: Chris Anderson

On Thursday, just before the infamous Tanenhaus panel, I attended the Chris Anderson talk on “The Long Tail,” which isn’t just an article anymore, but a full-fledged book coming out in July. Anderson was introduced by Will Schwalbe, the editor-in-chief at Hyperion. Schwalbe noted that Anderson has adopted an interesting speaking practice. He will speak to crowds for free, but he will only speak to those he can learn from. I suppose this means that remedial English classes might be out of luck for an Anderson lecture in the immediate future.

In any event, Anderson began his presentation by noting that March 21, 2000 was a very special day. It was special not because this was the first day of spring and certainly not because this was five days before the NASDAQ plummeted. Rather, Anderson insisted it was special because of *N Synch’s No Strings Attached sold somewhere in the area of one million copies that day. The album would later go on to sell 2.41 million copies. But Andreson was convinced that the *N Synch album was the peak of the blockbuster album. Anderson insisted that the considerable dip in albums since this treacly boy band arose from a cataclysmic shift in the music industry from an album world to a singles world. This was a case of the music industry losing leverage. And I’m sure you smart readers can see this coming, but this was a key indication of what Anderson has identified as “the long tail.”

In any event, Anderson began his presentation by noting that March 21, 2000 was a very special day. It was special not because this was the first day of spring and certainly not because this was five days before the NASDAQ plummeted. Rather, Anderson insisted it was special because of *N Synch’s No Strings Attached sold somewhere in the area of one million copies that day. The album would later go on to sell 2.41 million copies. But Andreson was convinced that the *N Synch album was the peak of the blockbuster album. Anderson insisted that the considerable dip in albums since this treacly boy band arose from a cataclysmic shift in the music industry from an album world to a singles world. This was a case of the music industry losing leverage. And I’m sure you smart readers can see this coming, but this was a key indication of what Anderson has identified as “the long tail.”

The long tail, not to be confused with a particular anatomical tuft on a rabbit, is, of course, Anderson’s very Gladwell-like theory which factors in the culture of specialization, economic theory, power law and a little bit of that ol’ pop culture just to seal the deal. The room, of course, was mobbed by interested parties, hoping to apply some of Anderson’s rules to the publishing industry.

While Anderson, equipped with a Powerpoint presentation and a slight grimace, seemed to be addressing his speech to a general crowd. (Generalized speeches about generalized arguments often will do that.) For anyone familiar with Anderson’s work or his findings, it won’t come as much of a surprise that an average of 25% of products live off the grid, as it were, representing that untallied array that still beckons with economic life (say, that record which your typical music clerk geek is hustling onto friends and family or that seemingly obscure book that has a small following). Where the 20th century was dominated by the bell curve, Anderson believes the 21st century will be governed by the long tail.

He offered five long tail lessons for the audience: (1) limited distribution with shared taste, (2) everyone deviates from the mainstream somewhere, (3) one size no longer fits all, (4) the best stuff isn’t necessarily at the top (see, e.g., Sturgeon’s law), and (5) the mass market is becoming a mass of niches.

Again, I was troubled that Anderson didn’t have a way of tying his interesting points in to the publishing industry. One can speculate and display Powerpoint slides until the cows come home, but, in the end, everyone needs a steak to throw onto the barbeque.

Don’t Get Between a Man and His Moleskine

LBC Gets BEA Streetcred

Chekhov & Pinky

Inexplicable Dog Attracts Interest at BEA

The Litbloggers (and Some Random Guy Standing in the Back) Will Kicketh Ass!

Sarah Weinman Wows Crowd with World Domination Scheme

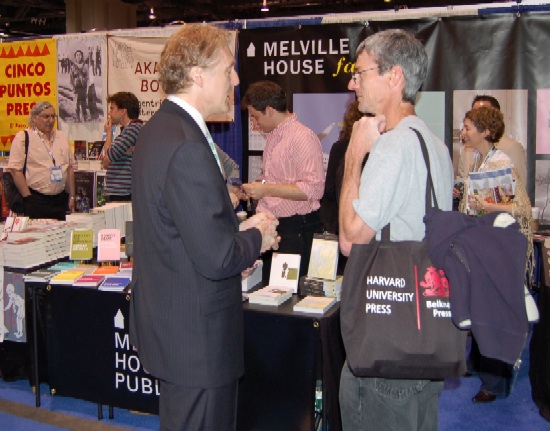

Dennis Loy Johnson Tries Out New Mind Control Techniques on Innocent Bystanders

BEA: Herein Lies Madness

One Kickass Subway

Charming View from a Best Western

Segundo Wreaks Havoc

Last night, I stayed in the hotel room rather than attend the party scene. But I understand that Bat Segundo, who flew in the plane with me, caused considerable trouble last night. Emails are coming in that Mr. Segundo was utterly rude to people and that he even started kissing and licking people and made horrible pronouncements and judgments. Had I known any of this, I would never have bought the plane ticket for Mr. Segundo, much less let him loose in any BEA festivities. We may have to rethink Mr. Segundo’s role in the grand scheme of things.

Strangely enough, it was Kevin Smokler was one of the few individuals to not only comprehend Mr. Segundo’s antics, but to actually get through to the troubled radio personality. Further, since we didn’t have the budget to hire a personal assistant, Carolyn Kellogg managed to trick Mr. Segundo and quell his ire through several drinks, as did the incomprable Megan Sullivan. I thank these individuals for doing their best to mollify Mr. Segundo’s abject temperament. Alas, with Mr. Segundo, it takes a junta to work miracles.

No More Gilbert Sorrentino

BEA: Do Not Question the NYTBR!

PANEL: The Best American Fiction Since 1980

Moderator: Sam Tanenhaus, Editor, The New York Times Book Review

Panelists: Greg Cowles (The New York Times Book Review), Thomas Mallon, Cynthia Ozick, Liesl Schillinger

At last year’s BEA, I didn’t get an opportunity to talk with Sam Tanenhaus about his continued failure to provide coverage on today’s contemporary fiction. The numbers, however, don’t lie. And they’ve been documented by Mr. Orthofer, Mr. Asher and me (via the Tanenhaus Brownie Watch). Repeatedly, Mr. Tanenhaus has not only demonstrated a failure to profile contemporary fiction (with scant space afforded to translated novels, experimental fiction and first novels by first author) in any thorough capacity, but he’s been outright deficient (as also determined years ago by Dennis Loy Johnson) on having women reviewers cover today’s books. (Indeed, it was a telling sign midway through the panel when Cynthia Ozick called Tanenhaus on failing to cite any women writers among his examples of what constitutes great literature.)

I’ve tried to interview Sam Tanenhaus multiple times to give him an opportunity to respond to these criticisms. But his office has repeatedly refused my interview requests. So what better way to bring these charges to light then through a public forum dedicated to celebrating how the New York Times Book Review determining the best fiction since 1980? Of course, I had to sit through a lot of surprising degree of defensiveness about WHAT MAKES THE NYTBR GREAT. But when the mike was deferred to Thomas Mallon and Cynthia Ozick, the panel became far more interesting. These moments, alas, were too few and far between. Fortunately, both Megan Sullivan and Sarah Weinman were good enough to accompany me.

Tanenhaus introduced the panel, speaking in a flat New York dialect somewhere between a overworked detective and an undertaker who wanted to get back to the basement and fix up the corpses. He repeatedly boomed key phrases into the mike. “I HOPE you will be pleased with the results.” At one point, perhaps reconciling the guy taking copious notes with the crazed litblogger who sent him benign brownie shipments, he took unsubtle care to note that the next issue was “DEVOTED ENTIRELY” to fiction — featuring reviews authored entirely by women.

Tanenhaus was initially quite defensive and a bit punchy. I wasn’t quite sure why. But it soon became clear that he preferred to dictate how people should react to the list rather than encourage them to read particular titles. “I urge EVERYONE to READ A.O. Scott’s ESSAY!” He urged the BEA staff to close the door early on, so that he might keep track of who was entering and leaving the room. I wondered for a moment if Tanenhaus’s inspiration was more Benito than Birkets. I expected men to come in hawking T-shirts reading “the few, the proud, the NYTBR.”

Tanenhaus described the fiction selection procedure as “a chimerical process.” But I remained dubious about the fanciful nature of when Greg Cowles (apparently, Tanenhaus’s right-hand man) described how he had painstakingly collected the data and composed the letters to the 200 judges. I’m glad Cowles is proud of his labors. Any good worker should be. But I don’t see how having a few Excel skills and knowing how to use mail merge can be described in any way as “chimerical.”

Tanenhaus had settled upon the 1980 figure, because it was “too easy” to fall back to 1941. The original inspiration for the contemporary fiction came from a 1965 poll in the New York Herald-Tribune, where 200 authors, editors and critics had been enlisted to determine the best work of fiction. Invisible Man came first. In addition to proving himself a whiz on the computer, Cowles, who would no doubt pass any of those temp agency tests with flying colors, also announced that he had been adept with microfilm machines. He had actually taken a microfilm of the old Herald-Tribune and placed it into a microfilm machine. Clearly, such achievements, well within the abilities of any grad student working on a thesis, demonstrate that the NYTBR has gone above and beyond the call of duty. To give Tanenhaus and Cowles the benefit of the doubt, ask yourself this question: how many deputy newspaper editors do you know who can do this? Then ask yourself a second question: how many deputy newspaper editors do you actually know?

Tanenhaus didn’t go into the criteria on how he had selected the judges, save that it was “a jury of peers” which beckoned his attentions. He approached 200 people and confessed that many people had written back very angry letters. One unnamed author had suggested that he was “out-Oprahing Oprah.” There was also a good deal of argument over Donald Barthelmie’s 60 Stories, because the material had been published before 1980. So had the book. But it had won the American Book Award in 1980. Thus, it was eligible. There were also a few authors who had voted for themselves.

Such pedantics were tossed out by Tanenhaus again and again. And it suggested to me that Tanenhaus seemed more fond of the idea of being the cultural arbiter rather than the culture itself. It can’t be an accident that Tanenhaus referred himself thrice during the panel as a “self-appointed vulgarian.” (Presumably, this dud of a self-effacing joke was uttered because the audience did not laugh the first two times.)

Fortunately, the divine Cynthia Ozick, who looked bored out of her mind while Tanenhaus spoke, mercifully interjected, noting that it might have been better to nominate writers rather than absolute titles. But she did give Beloved high praise, calling it a deeply enshrined book, “elliptical, elusive, poeticized.”

Liesl Schillinger cited Zadie Smith’s On Beauty as an example of a book demonstrating “how strongly and vehemently we can disagree.” Well, disagreeing is one thing. But how is shouting “On Beauty sucks, dude!” an effective way of gauging contemporary fiction?

Thomas Mallon, who, along with Ozick, was the most interesting of the panelists, voted for Underworld. He suggested that Morrison had written better books than Beloved. But had he been nailed down to single out a writer, a la Ozick, he likely would have selected Philip Roth. Mallon remarked on the conservatism of his fellow judges. Where were the writers from the younger generation? He also remarked that fewer novelists were willing to write reviews, much less start feuds.

It was, indeed, the feud component that Tanenhaus picked up on and that seemed to interest him more than the conservatism of the choices. He noted that Chip McGrath had told him that it was almost impossible to persuade younger novelists to review their contemporaries without first reviewing the galleys. He suggested that this might be a “generational question.”

Ozick responded by saying, “I believe in temperaments, not in generations.” She pointed out that she had selected William Gaddis’s Carpenter’s Gothic, pointing out the distinct way that it used language.

Mallon noted that most of the writers who came of age between the 1930s and the 1940s were probably better nonfiction writers. He also noted that there was not as vital and vibrant a magazine culture now as there was in the 1960s.

Schillinger was asked about the silly V.S. Naipul essay by Tanenhaus and confessed that her favorite writer was Anne Tyler. But she did note, citing E.M. Forester, that because things change so fast, people can’t quite set their worlds down.

Revealing his middlebrow tastes, Tanenhaus openly confessed that he was surprised that Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, which he viewed as a high watermark novel of the last six years, hadn’t been selected. He then tried to get the conversation going on whether Updike was considered “a political writer.” Ozick noted that, “I think he thinks he is,” but pointed out that Updike was good with domestic politics.

Mallon believed that immigration would be the key political issue to invigorate contemporary fiction.

Sam Tanenhaus boasted how he does a podcast now.

Exposing the troubling similarities between marketing language oxymorons and the NYTBR‘s troubling critical worth, Schillinger cited Curtis Sittenfeld’s Prep as “an instant classic.”

Eventually, the floor was open to questions.

I stood up and pointed out to Tanenhaus that the list of judges was mostly male and that this reflected a continuing trend by the NYTBR as a whole to give the majority of its reviews to men over women. I also asked how a weekly book review section that continued to prioritize nonfiction over fiction could legitimately put out a “Best Contemporary Fiction” list. I then revealed myself to be the Tanenhaus Brownie Watch guy and playfully asked why I hadn’t received a single thank you note for the brownies. “Is this a New York thing?” I asked.

Tanenhaus took considerable ire at this, booming into the microphone with all the joie de vivre of a stale jelly bean, “Where do we begin?” On the judges list question, he pointed out that the original list of 200 had a more equitable balance between men and women. But that women writers declined to be involved with the project more than men. He was again defensive about the NYTBR, suggesting that “we don’t fill quotas” and, instead of responding to my points, declared the NYTBR the best book review section in the nation. (Of coure, had I been permitted to interject on the fiction coverage in the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Washington Post, the San Francisco Chronicle or even the Baltimore Sun, I would have. But Tanenhaus clearly wanted to evade the issue.)

As to the question of the brownies, Tanenhaus boomed into the mike:

“WE ARE UNDER NO OBLIGATION TO ACKNOWLEDGE THE BROWNIES!”

And there, beyond the fact that this extremely silly sentence was uttered with seriousness, is the problem.

The brownies could be experimental fiction. They could be poetry. They could be novels in translation. But Tanenhaus simply will not “cater to anyone” or “acknowledge” them. In the Tanenhaus world, it is Jonathan Franzen or a particularly sycophantic deputy named Cowles who matters more than anything else.

And so I think my work here is at an end. I can now say with absolute certainty that the New York Times Book Review is hopelessly conflicted, hopelessly out-of-touch and worthless to anyone who cares about literature. It is beyond repair. And its head administrator has a limited sense of humor to boot.

Is it little wonder, given these attitudes and lack of flexibility, that newspapers have stopped mattering?

[UPDATE: Scott Esposito, who sadly isn’t here, has thought quite a bit about the Tanenhaus list and has some thoughts on the subject.]

[UPDATE 2: Ron and Sarah have more of the specifics between the Tanenhaus-Champion showdown. And there is one key question that lingers: why did so many women say no to Tanenhaus’s project?]

The Boys at Skyline Books Pay Rapt Attention to Your Needs

From the BEA Floor

A New Lease on NASCAR?

Ron, Kassia and Company

Chris Anderson Delivers “Long Tail” Speech

Run, Tanenhaus, Run!

Sam Tanenhaus Isn’t Having Much Fun in DC

BEA: More to Follow

More BEA reports to follow, including Chris Anderson’s speech presaging his forthcoming The Long Tail book and the Sam Tanenhaus panel, in which your correspondent questioned Tanenhaus about his male-centric offerings in a playful way, watched Tanenhaus take it personally and was answered with a very public damnation of the brownies that we had sent him in the past. “The NYTBR caters to nobody!” he insisted.

Quibble with me all you want, Mr. Tanenhaus. But the brownies were lovingly baked and sent to you, sir! They meant you no harm! Must you take out your umbrage upon a harmless slat of baked goods? The brownies, it seems, will remain denied. For good.

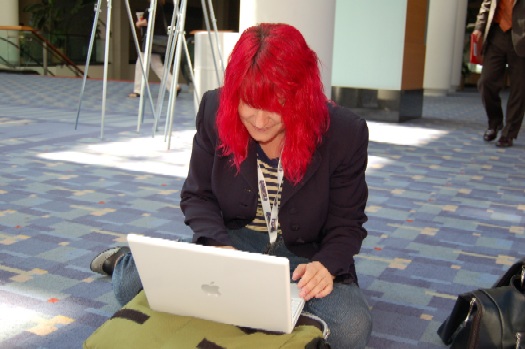

BEA: Shaky Connection

Apologies for being a bit slow on the draw. The wi-fi situation is extremely dicey and has been affecting all bloggers covering the event. But I hope to offer as much coverage as I can.

Pinky’s Paperhaus on the BEA Floor

BEA: Podcast Panel Report

Make no mistake. BookExpo America is an industry convention. If something here looks, feels or breathes cash potential, the men dressed in blue blazers and the well-coiffed and often middle-aged women dressed in conservative skirts rarely extending above the knee will be on it like loyal johns courting a favorite prostitute.

The hell of it is, nobody really knows what they’re doing. Least of all the panelists.

There was no better indication of this then this morning’s disastrous “How to Leverage a Podcast” panel, which Carolyn Kellogg and I (both of us being podcasters and both of us being more than a bit curious about how marketing language sashays with the medium) attended by the slimmest of time margins. A slick-sounding, bearded man by the unlikely name of Tee Morris led the proceedings. Morris, who hadn’t even bothered to don a business suit for this almighty trade show, was the author of Podcasting for Dummies. The room was filled with starry-eyed entrepreneurs looking up at this marketing majordomo and feeling a bit disappointed. He came across as a huckster without a clear plan. Many of the people walked out of the presentation, in large part because Morris’s approach was more “MAKE MONEY FAST!” than any practical summation of how a podcast can generate revenue or what it could do for publishing or how it could be ABOUT something.

In a mystifying move, Morris didn’t really zero in on publishing-based podcasts until forced into topical alignment by the slightly more coherent Rob Simon (the man behind this year’s BEA podcasts), who, rather fittingly, stood behind a podium on a slightly raised dais while Morris gesticulated on the ground floor.

In a mystifying move, Morris didn’t really zero in on publishing-based podcasts until forced into topical alignment by the slightly more coherent Rob Simon (the man behind this year’s BEA podcasts), who, rather fittingly, stood behind a podium on a slightly raised dais while Morris gesticulated on the ground floor.

What were, for example, the Battlestar Galactica podcasts? “It’s basically a director’s commentary on demand!” exclaimed Morris.

There were even some crazy gender assertions. “Women are [making podcasts] better than men. They are just keeping quiet about it.”

Morris seemed particularly proud of the way one publishing house (he couldn’t identify whether it was Simon & Schuster or Random House) came specifically to one particular podcast for sponsorship. And he failed to offer a clear plan to the hopeful attendees other than to get podcasts listed on major directories and try and get linked by other sites.

Perhaps intoxicated by the Web 2.0 fervor, Morris tossed all manner of buzz words and catchphrases into the fray.

“Podcasting enhances publishing.”

“Podcasting is the next big thing.”

He even quoted McLuhan’s motto, “The medium is the message.”

Carolyn and I watched slackjawed as Morris fumbled repeatedly, failing to point out the “literary” in “literary podcast.” Despite his unabashed zeal, Morris dodged one fundamental thing that makes podcasts work: the fact that they have an identity that runs counter to the bland conduits of corporate radio. He never suggested once to the podcasting hopefuls that they might learn a few lessons by, say, listening to a few podcasts before making a strike for the mythical cash vein.

Carolyn and I watched slackjawed as Morris fumbled repeatedly, failing to point out the “literary” in “literary podcast.” Despite his unabashed zeal, Morris dodged one fundamental thing that makes podcasts work: the fact that they have an identity that runs counter to the bland conduits of corporate radio. He never suggested once to the podcasting hopefuls that they might learn a few lessons by, say, listening to a few podcasts before making a strike for the mythical cash vein.

And can one really trust a guy who refers to himself in the third person? “If you’ve never heard of Tee Morris until today,” Morris started, “you will eventually.”

Other Morris points of wisdom: “People like that behind-the-scenes stuff!” Who exactly? What constitutes “behind-the-scenes stuff?”

“Podcasts need to be branded!” How?

There was an attempt by Rob Simon at coining a new catchphrase: “Think outside the book.” Apart from the bastardization of a now tired corporate buzz phrase, shouldn’t a publishing-based podcast be thinking very much inside the bok?

Morris also cited Cory Doctorow as an example of a successful podcaster, but failed to note that he also runs Boing Boing, one of the most popular blogs on the planet and that this may have had a bit of a hand in getting people to listen to the podcast.

Morris did have a few good points, such as the idea of using a podcast to reach to the hard-to-reach white male audience in publishing. But even this still limns Morris’s troubling approach, perhaps symptomatic of most of the Web 2.0 panels here: throw heaps of statistics at the crowd and expect them to draw mystifying associations.

Welcome to the publishing industry.

Now We’re Off…

…proper. See you at BEA!

So in DC, Look for the Guy Who Looks Like Hugo Weaving?

UPDATE: Since Tayari tried it again, I put another photo through and got this:

Okay, I can live with that: Val Kilmer and Hugo Weaving’s bastard love-child. But let’s try a third photo:

Joaquin Phoenix? Something is terribly wrong with this machine!