This program contains three segments. The main one is with Dorthe Nors, who is most recently the author of Karate Chop. There is also a brief Blake Bailey interview. He is most recently the author of The Splendid Things We Planned. And our introductory segment involves the Save NYPL campaign.

Guests: Dorthe Nors, Blake Bailey, members of the Save NYPL campaign, Matthew Zadrozny, members of Raging Grannies.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

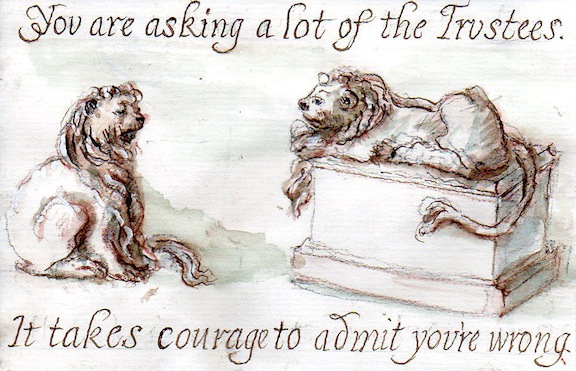

Subjects Discussed: Mayor Bill de Blasio’s failure to live up to his July 2013 promise to save the New York Public Library, the greed of rich people, political opportunism, Charles Jackson, The Splendid Things We Planned, the differences between biography and memoir, being the hero of your own story, subjectivity as a great muddler, the Bailey family’s tendency to destroy cars, being self-destructive, contending with a brother who threw his life away, the problems that emerge from being cold, the differences between American and Danish winters, unplanned writing, the swift composition of Beatles lyrics, the courageous existential spirit within Swedish literature, Danish precision, the Højskolesangbogen tradition, the influence of song upon prose, Kerstin Ekman, Nors’s stylistic break from the Swedish masters, Ingmar Bergman, Flaubert’s calm and orderly life, the human-animal connections within Karate Chop, considering the idea that animals may be better revealers of human character than humans, animals as mirrors, emotional connections to dogs, the human need to embrace innocence, judging people by how they treat their pets, “The Heron,” friendship built on grotesque trust, how the gift exchange aspect of friendship can become tainted or turn abusive, writing “The Buddhist” without providing a source for the protagonist’s rage, how much fiction should explain psychological motive, the hidden danger contained within people who think they are good, how Lutherans can be duped, “missionary positions,” Buddhism as a disguise, ideologies within Denmark, when small nations feel big and smug, Scandinavian egotism, Danesplaining, whether Americans or Danes behave worse in foreign nations, buffoonish American presidential candidates, how “The Heron” got to The New Yorker, Nors’s early American advocates, being a tour guide for Rick Moody and Junot Diaz, how Fiona Maazel brought Dorthe Nors’s fiction to America, Copehagen’s Frederiksberg Gardens as a place to find happiness, happiness as a form of prestige, when happy people feel needlessly superior, Denmark’s subtle efforts to win the happiest nation on earth award, setting stories in New York, how different people react to large tomato, Stephen Jay Gould’s The Mismeasure of Man, how measuring objects reveals aspects of humanity, the tomato as the Holy Grail, flour babies, why strategically minded people shouldn’t be trusted, the creepy nature of control freaks, how human interpretation is enslaved by representations, competing representations of reality, whether fiction is a more authentic representation of reality, how disturbing ideas presented in books can calm you down, exploring the Danish idea of a den to eat cookies, working with translator Martin Aitken, what other nations get wrong about Denmark, Hans Christian Andersen, superficial knowledge of Denmark, Danish writers who need to be translated, Yahya Hassan, and Danish crime fiction.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I wanted to talk about the economy of these stories, which is fascinating. I mean, you have to pay very close attention to learn the details and to learn some very interesting twist or some human revelation in these stories. So this leads me to ask — just to start off here — I’m wondering how long it takes for you to write one or to conceive one. Is there a lot of planning that goes into the idea of “Aha! I’ll have the twist at this point!” I mean, what’s the level of intuition vs. the level of just really getting it down and burying all the details like this?

Nors: I don’t plan writing. It happens. Or I get an idea or I see something. Or there’s a line or a passage that I write down. And sometimes it just lies there for a while. Then a couple of days later, I will write another passage, perhaps for another story, and sometimes I put them together. They start doing things. But I write them pretty fast. When the idea and the flow and the voice and the characters are there, I just go into the zone and it kind of feels like I’m singing these. It’s like you find the voice for a story and you just stick to it and write it. It doesn’t take that long. Seven of these stories were actually written in a cottage off the west coast in Denmark. Two weeks.

Correspondent: Two weeks?

Nors: Yes.

Correspondent: For seven of the stories?

Nors: Seven of the stories.

Correspondent: Wow.

Nors: And then I would take long walks and I would go home. Boom. There was this story. So the writing process with this one, it was like that.

Correspondent: That’s like the Beatles writing the lyrics for “A Hard Day’s Night” on the back of a matchbox in ten minutes.

Nors: When it happens, it happens, right?

Correspondent: Well, to what do you attribute these incredible subconscious details? Are these details just coming from your subconscious and they’re naturally springing? Or are they discovered in the revision at all?

Nors: I think they come from training. Because it has something to do with the neck of the woods that I come from. Scandinavia. I was trained in Swedish literature. That was what I studied at university. And the Swedes have this very bold and courageous brave way of looking at existence. I mean, it turns big on them. And they look at the darkness and the pits of distress and everything. Then if you take that richness of existentialism, you might even call it, and pair it up with the Danish tradition — which is precision, accuracy, Danish design, cut to the core, don’t battle on forever. If you combine these two, you get short shorts with huge content that is laying in there like an elephant in a container and moving around all the time. And this style came from training. This came from reading a lot and writing a lot. Suddenly, I think I found my voice in these stories. I think this was a breakthrough for me in Denmark also. That I found out how I can combine the Danish and the Swedish tradition.

Correspondent: So by training, how much writing did you have to do before you could nail this remarkable approach to find the elephant, to tackle existence like this?

Nors: Well, I started writing at eight. And this book was written when I was 36.

Correspondent: But you didn’t have the Danish masters and the Swedish masters staring over you at eight, did you?

Nors: No. But I had the Danish song tradition. We have a book in Denmark called Højskolesangbogen. You’ll never learn how to say that. But it’s a songbook.

Correspondent: (laughs) She says confidently. You never know. I might learn!

Nors: You wanna try? But that songbook — in the real part of Denmark that I come from, all the farmers, they would use that songbook a lot. And there was no literature in my household. It was middle-class. A carpenter and a hairdresser. But this book was there. And what I learned from that was that these songs, they were written by great Danish poets and then put into music. It would be so precise. I love that book. I sang these songs. I read these poems. And then later on, there was my brother’s vinyl covers. It was Leonard Cohen. It was all these guys that he had up in his room and I could read. And a lot of the training came from that. And then later on, university, of course, and the boring part of training.

Correspondent: The analytical stuff. Well, that makes total sense. Because there is a definitive metric to these particular stories. You mentioned that they were akin to singing. And I’m wondering how you became more acquainted with this musicality as the stories have continued. And also, how does this work in terms of your novels? Which are not translated. There are five of them. And those are obviously a lot larger than a short story. So how does the musicality and that concise mode work with the novels?

Nors: Well, I think my first novel was extremely influenced by a Swedish writer called Kerstin Ekman, who I wrote my thesis on. And it was so influenced by her that I kind of shun away from it. Because I don’t want to sound like her anymore. And then on my third book, I started to find that the voice that blooms in Karate Chop — and there’s a breakaway there; it’s like a break in my writing.

Correspondent: A karate chop!

Nors: It really is! Because the first three of my novels were classic structures. They had plots and peaks and this whole Swedish abyss of existentialism and darkness. But then with this one, I broke away. And the next two novels I wrote are short novels. And they’re more experimental in their form and they’re very close to the whole idea of accuracy. And that line, that sentence, has to be so precise. And it has to sing. And it has to have voice. And it has to be just so accurate. That’s the sheer joy for me: to actually be able to write a sentence and to know people will get this.

Correspondent: This is extraordinary. Because if you’re writing a short story so quickly, and it’s not singing, what do you do? I mean, certainly, I presume that you will eventually sing in this mode that you want to. But that’s a remarkable speed there. So how do you keep the voice purring?

Nors: Well, actually, I do a lot of reading out loud while I do it. And the rhythm has to be good when I read it aloud myself. I talk a lot. I walk a lot. And I think literature like this has a lot to do with listening to how the words sound and how they work together. But that’s an intuitive thing. There’s no math in this. Either you can carry a tune or you can’t perhaps, right?

Correspondent: Sure. Absolutely.

Nors: So it’s something instinctive, I think.

Correspondent: I’m curious to know more about the tension between the Swedish existential dread and angst and the Danish identity. You touched upon this a little bit. I saw your little Atlantic soliloquy about Bergman and how you looked to him as a way of living a tranquil life and not living a wild life, which gets in the way of…well, gets in the way of living, frankly.

Nors: Exactly.

Correspondent: I’m wondering. What do you do to live or draw upon experience or to move into uncomfortable areas? Or is your imagination stronger than that? That you don’t really need the life experience. Your imagination in combination with the singing that we’re identifying here is enough to live a tranquil life? Or what? And also, I was hoping you could talk about the tension between the Swedish and Danish feelings and all that.

Nors: First of all, I try to live my life as any other human being. I just try not to really be destructive about it. I’m 43. I’m not afraid to tell you how old I am. So I tried a lot in my life and a lot of it has been dramatic. And it has been filled with emotions and breakups and stuff like that. And, of course, I draw on the experience from that. But these days, I think the discipline is very important. I don’t need more drama in my life. I don’t know why you should seek out drama. Causing pain in your life? That’s an immature thing to do at my age, I think. You can’t avoid it. It’s going to happen anyway. People you love will pass away. Your cat will be hit by a car. Or stuff like that. You don’t have to seek it out. It’s coming to you.

Correspondent: But I’m wondering if that impulse isn’t necessarily a writerly impulse, but just a human impulse. Because when we get closer to forty, we start to say, “Well, do we really want to live this way?” Our choices sometimes become a little more limited. Our responsibilities are greater. We now have a duty to other people. And so is that really a writerly thing? I mean, is the writer doomed in some sense to almost be a child to some degree?

Nors: I think you’re absolutely right. I don’t think it’s necessarily a writer thing. I think it’s a time in your life where you think that. Or you go haywire and you go right into the abyss, right? Ingamr Bergman was around 47 when this happened for him. Because he lived a pretty crazy life. Having children all over the place and women. Pretty destructive.

Correspondent: Locking Liv Ullmann up.

Nors: Yeah, exactly. Being very chaotic. An emotionally chaotic life. And then around this age, he took this path also of not living like a monk. Because he certainly didn’t. But he was just very structured and disciplined. And I enjoy that. It sounds boring to people. But I really enjoy it. Don’t need more drama in my life.

(Loops for this program provided by Martin Minor, Mooz, 40A, Tim Beets, Tim Beets, Aien, and DANB10.)

The Bat Segundo Show #538: Dorthe Nors, Save NYPL, and Blake Bailey (Download MP3)