(This is the thirty-fourth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: Main Street.)

Hello, Darkness, my old friend. I’ve come to talk with you again. Except that I don’t particularly want to. It’s not you, Joe. It’s me.

Don’t worry. We’ll still text each other. I’ll still speak fondly of you. We can still meet for Sunday brunch sometimes. I’m just in a different place these days. Namely the 21st century.

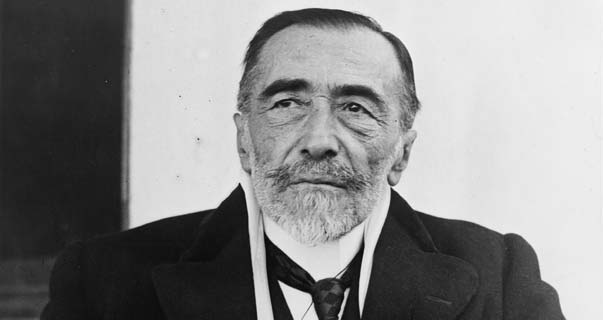

It can’t be an accident that the wildly underrated Julian MacLaren-Ross skewered the idea of reading Conrad as an upwardly mobile class aspiration in Of Love and Hunger. In Frog, Stephen Dixon took the piss out of Conrad along these lines as well. Indeed, slagging off Conrad seems to be a common trait among many of my literary Bohemian heroes. And I do need to heed them. I feel and trust their instincts. It’s almost as if we’re told that we should simply accept that Conrad is a great writer who changed the course of literature (and he did) even as we pretend that he isn’t ancient and hoary and horribly regressive. When I confessed my reluctance to reread Heart of Darkness to a few friends, they told me, “Well, it’s only a hundred pages.” Which suggested very strongly that nobody really wants to read Conrad anymore. He doesn’t pop out at you like Joyce or Faulkner or Nabokov or even Lawrence. And, to tell you the truth, I would much rather reread Finnegans Wake than anything from Conrad.

It can’t be an accident that the wildly underrated Julian MacLaren-Ross skewered the idea of reading Conrad as an upwardly mobile class aspiration in Of Love and Hunger. In Frog, Stephen Dixon took the piss out of Conrad along these lines as well. Indeed, slagging off Conrad seems to be a common trait among many of my literary Bohemian heroes. And I do need to heed them. I feel and trust their instincts. It’s almost as if we’re told that we should simply accept that Conrad is a great writer who changed the course of literature (and he did) even as we pretend that he isn’t ancient and hoary and horribly regressive. When I confessed my reluctance to reread Heart of Darkness to a few friends, they told me, “Well, it’s only a hundred pages.” Which suggested very strongly that nobody really wants to read Conrad anymore. He doesn’t pop out at you like Joyce or Faulkner or Nabokov or even Lawrence. And, to tell you the truth, I would much rather reread Finnegans Wake than anything from Conrad.

Yet I don’t detest Conrad. Certainly not with the full-bore commitment in which I direct my fierce energies loathing Henry James — a man who is represented on the Modern Library canon with three hideous doorstoppers and who I have tried to learn how to enjoy (even enlisting the tremendously gracious Dinitia Smith for assistance), but whose “charms” I have proven totally impervious to. And since I’m getting ever closer to fifty and there hasn’t been a break in the Henry James ice floe, I suspect that I’m fated to go to my grave hating him, possibly living a few extra months not only to spite my enemies, but to deliver a few final rounds of vitriol towards one of the most overrated and egotistical writers in the English language. I truly dread the James slog that’s in store for me about forty titles from now. The horror! The horror! Perhaps I shall be driven mad like Kurtz.

But not so with Conrad! There is much about Conrad to like: his intensity, his often beautiful imagery, and his insights into human atavism. Eleven years ago, Lord Jim did hold my attention — but I had to give Conrad everything that I had. Decades before I read Lord Jim, I was dazzled by Heart of Darkness in high school. I reread it twice in the last few months and, while the allure that once hypnotized me seems to be gone, I can’t gainsay that this is a masterpiece.

First off, I think we can all agree that Marlow is one of the most long-winded bastards in all of literature. “Mansplaining” doesn’t even begin to describe the dude’s incessant need to talk. Compared to your FOX News-watching uncle going on and on about Marxist conspiracies at the Thanksgiving table, Charlie Marlow is an outright conversational tyrant. All these poor sailors want to do is play dominoes, but the unnamed passenger listening to Marlow’s tale notes that only “the bond of the sea” keeps the sailors from bitching about this incessant rambler “so often unaware of what [his] audience would best like to hear.” (Incidentally, this two-layer approach to narrative is a shrewd move by Conrad to insulate himself from any charges of planting autobiography into his fiction. Conrad and Marlow share many similarities. Not only did Conrad go to the Congo to fulfill a boyhood dream, but he also, like Marlow, endured the stench of a fresh corpse while commanding a steamer. Small wonder that the Polish-Ukranian bard decided to devote all of his time and energies to a full-time writing career not long after this hideous tour of duty.)

Graying technophobes — the kind of unadventurous dullards best epitomized in today’s literary world by the likes of Jonathan Franzen and Sven Birkerts — often complain about the Internet’s impact on attention spans. But consider the alternative. Do you honestly want to live in a pre-radio world in which men explain things with indefatigable logorrhea? In this case, we have Marlow counterbalancing the “savage” world with the “civilized.” There were points in which I felt great sorrow for the poor sailors and imagined sending smartphones back in time so that these poor men could wile away their hours with Candy Crush and cat videos instead of listening to a reactionary seaman splaying out his white supremacy.

And about that white supremacy. Chinua Achebe has been perhaps the most vocal literary figure who has denounced Heart of Darkness, calling Conrad “a thoroughgoing racist,” rightly impugning Conrad’s belittling and dehumanization of Africa, and pointing out how Conrad’s “generosity” in having Black people show up for token cameos is anything but. Achebe scolds Conrad for avoiding the word “brother” in lieu of “kinship” in relation to Black people. (Indeed, the ocean itself, described as “a positive pleasure, like the speech of a brother,” gets more dignity than the dark-skinned “natives” of this tale.) What draws Marlow to Africa on a map is “a white patch for a boy to dream gloriously over.”

On the other hand, there is some modest pushback when the Company’s office is compared to a “whited sepulchre.” Smoke from gunpowder is described as “white,” thus suggesting some white complicity. Can we likewise interpret Marlow pointing to the Blacks being unable to distinguish between individual white men as “being so much alike at a distance” as an acknowledgment of Marlow’s tendency to do the same with Black people? And what are we to make of the white worsted tied around the neck of a dying Black man? Or the foreman whose beard is tied up in “a kind of white serviette he brought for the purpose”? Or a book “lovingly stitched afresh with white cotton thread”? Or the “cold and monumental whiteness” of a marble fireplace?

Humorless sods like Jonathan Jones have written masturbatory articles defending Conrad (and dissing Achebe) with all the clueless gusto of a Trump cultist declaring noted Hungarian tyrant Viktor Orban “a good guy.” But the truth of Conrad’s racism is somewhere in between. Conrad was racist. (The N-word appears ten times within Heart of Darkness‘s 38,000 pages. And the Black caricatures are frequently sickening.) Like all great writers, he executed his storytelling with instinctive ambiguity. And since many of the colonialists carry remnants of white, Conrad’s imagery — whether intentional or not — can also be read as condemnatory of imperialism and privilege.

And you cannot deny Conrad’s commitment to atmosphere! The old woman who greets Marlow with “flat cloth slippers…propped up on a foot warmer, and a cat reposed on a lap.” The Eldorado Exploring Expedition manager who resembles “a butcher in a poor neighbourhood.” The “torn curtain of red twill” hanging in the doorway of a hut that “flapped sadly in our faces.” A “long, decaying building on the summit…half buried in the high grass.” For all of Marlow’s garrulity, Conrad was a master of imagery, knowing the exact measure of words — never too many, never too few — to connote this tropical world.

Still, for all my complaints about Conrad’s racism, Kurtz is truly one of the all-time creepy fucks of literature. On one hand, we are told that “Mr. Kurtz lacked restraint in the gratification of his various lusts” and that he is possibly mad. But his seemingly calm rationalization about how he has manipulated the world around him is deeply unsettling. And while Conrad suggests that Kurtz has become this way because of uncharted and unfamiliar terrain (“The long shadows of the forests had slipped downhill as we talked”), it is quite likely that Kurtz was always unhinged. And if this is indeed the case, then Conrad is saying something very vital about the tyranny of white privilege, even if it comes saddled with tacit endorsement.

Next Up: W. Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage!

Much like today’s tawdry Hollywood movies, Lord Jim was based on a true story — back in the days when it actually meant something. On August 7, 1880, a ship called the Jeddah, on its way from Singapore to Arabia and carrying 950 Muslim pilgrims, had an accident. The British officers abandoned the ship near Cape Gardafui. But the Jeddah did not sink. Captain Clark was on his way out of the British Consulate when another captain reported that the Jeddah had been salvaged and towed. Clark got off lightly. His certificate was stripped for three years. But the Jeddah‘s first mate, Augustine Podmore Williams, received a harsher sentence.

Much like today’s tawdry Hollywood movies, Lord Jim was based on a true story — back in the days when it actually meant something. On August 7, 1880, a ship called the Jeddah, on its way from Singapore to Arabia and carrying 950 Muslim pilgrims, had an accident. The British officers abandoned the ship near Cape Gardafui. But the Jeddah did not sink. Captain Clark was on his way out of the British Consulate when another captain reported that the Jeddah had been salvaged and towed. Clark got off lightly. His certificate was stripped for three years. But the Jeddah‘s first mate, Augustine Podmore Williams, received a harsher sentence.

Correspondent: I wanted to ask you about “Dictation,” the title story. This was very interesting to me for a number of reasons. Because here you have two writers, Henry James and Joseph Conrad, two secretaries of Henry James and Joseph Conrad, and then on top of that, you have a number of repetitions throughout the story, as if to echo or beckon the typewriter. Like in the very beginning, when you have Henry James describing Almayer’s Folly, you kept saying, “He saw. He saw.” And there’s a number of interesting things you are doing in the syntax of the story that almost echoes the typewriter. So I wanted to ask how this particular stylistic device came about. I know you spend a lot of time on your sentences. So you had to have been at least somewhat aware of this.

Correspondent: I wanted to ask you about “Dictation,” the title story. This was very interesting to me for a number of reasons. Because here you have two writers, Henry James and Joseph Conrad, two secretaries of Henry James and Joseph Conrad, and then on top of that, you have a number of repetitions throughout the story, as if to echo or beckon the typewriter. Like in the very beginning, when you have Henry James describing Almayer’s Folly, you kept saying, “He saw. He saw.” And there’s a number of interesting things you are doing in the syntax of the story that almost echoes the typewriter. So I wanted to ask how this particular stylistic device came about. I know you spend a lot of time on your sentences. So you had to have been at least somewhat aware of this.