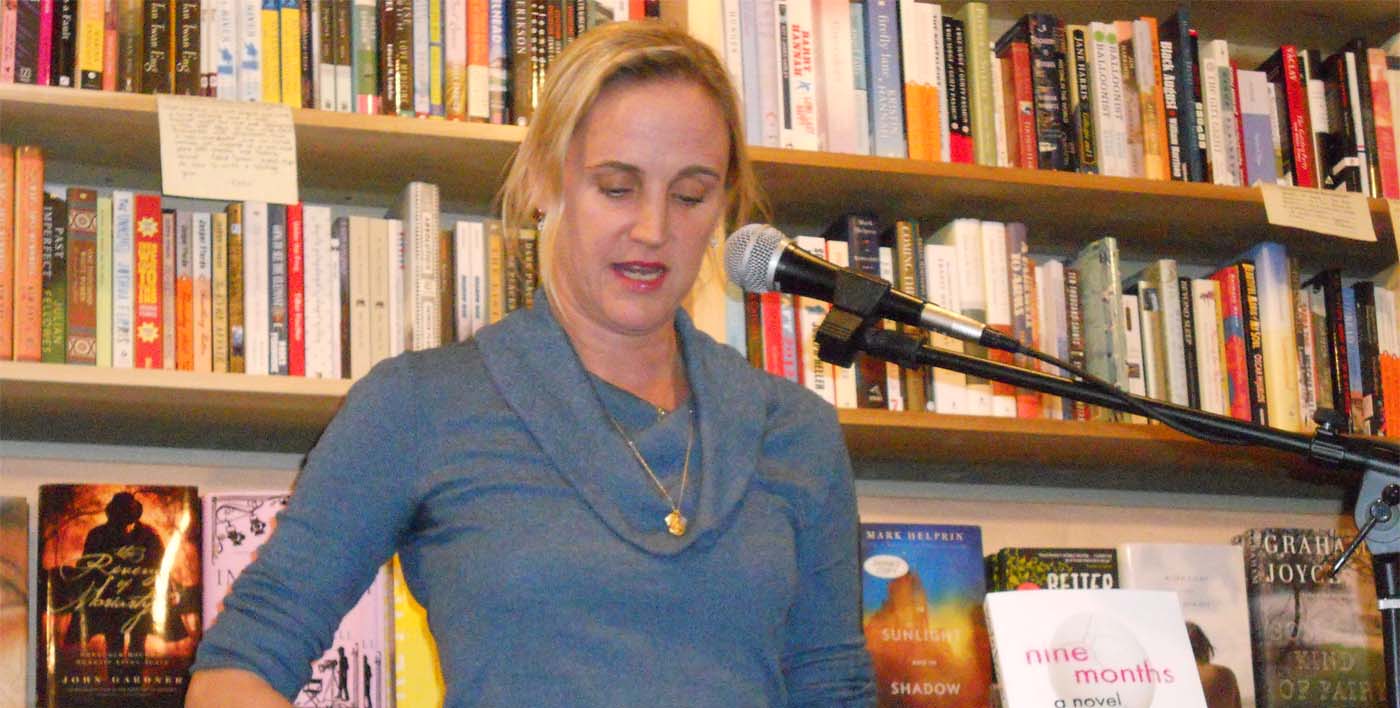

Joanna Rakoff is most recently the author of My Salinger Life.

Author: Joanna Rakoff

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: Responding to the universe’s concerns with short declaratory bursts, self-portrayal in memoir, bygone tones that aren’t nostalgic, growing up with Depression era parents, being enslaved by grammatical constructs, hostility to contractions, The Yellow Eyes of Crocodiles, bad translations, disputes over which literary agency is New York’s oldest, the coddled affluent lifestyle, working as a PA on The Mirror Has Two Faces, bouncing around jobs as an act of rebellion, growing up in privilege, contending with a family dynamic of trying to live life while parents discourage risk, keeping details “close to the bone,” having a temperament a generation above, working in an Agency using ancient typewriters, working in an office opposed to modern technology, typing letters on carbon paper, the beginnings of computer communications in 1996, working in an office without voicemail, the benefits of archaic office structure, lengthy lunches, the advantages of working with your hands, S.J. Perelman, Pearl Buck, 20th century writers who fell out of favor but that line bookshelves of older people’s homes, the buzz that one can get from using an IBM Selectric, typewriter dreams, why J.D. Salinger is scoffed out by adults, the Salinger documentary, Bret Easton Ellis’s Salinger tweet, Martin Amis, Infinite Jest, the literary masculine movement of 1996, not reading Salinger in college, Salinger’s stories in the New Yorker, family bonding through Franny and Zooey, answering Salinger fan mail, observing when Judy Blume switched agencies, misunderstanding the appeal of Judy Blume, keeping contemporary reading sensibilities alive at the Agency when facing doughty pushback, the literary sensibilities of Phyllis Westberg, the shift in publishing short fiction during the last years of the 20th century, Blume and Claire M. Smith, agents and friendship, the backstory on how Summer Sisters was misperceived before publication, why it’s important for agents to offer love and praise to authors, reading for agents, talking up manuscripts written by college friends, Myla Goldberg’s Bee Season, developing the inclinations to be an editor and a critic, whether being employed by a slick Wylie-style agency would have turned Rakoff into a writer, how agents shape culture, the double-edged sword of keeping a journal as a young person, socialist boyfriends as a cautionary tale, secretly carving out time to write stories, Pathfinder Books, being a morning person, writing with kids, Sylvia Plath’s diary, boyfriend “Don”‘s aversion to office jobs and bourgeois accusations, contending with male nonsense, disparaging boyfriends, having literary sensibilities shaken up, operating in two literary universes, boxing memoirs, contending with being depicted in Robert Anasi’s The Last Bohemia, why Rakoff didn’t name names in the book version (and did in the Slate version), trying to nail the universal experience of My Salinger Year, overlapping cultures in New York, the DIY aesthetic, spoken word culture, the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, whether the 1996 Joanna Rakoff could have survived 2014 New York, the difficulty of making ends meet, being detached from open mike culture, expensive cities, purported claims of subsisting on almost nothing in Cambridge, transient arts scenes, the Hudson River Valley, whether young people can have their Salinger year in New York, and parental supplementation.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I wanted to actually start off with the tone of the book. I mean, you present yourself in this memoir as someone who responds to the universe’s concerns with these short, declaratory bursts. When you are asked questions about how equipped you are to handle your role as an agent’s assistant and your responsibilities as an adult, you often answer, “I can.” “I do.” “I am.” “It is.” “I understand.” Never “yes,” which I found really interesting. And it leads me to wonder whether this laconic approach is perhaps the best way to negotiate early life and to sort of figure out what the beginnings of life are. How is this self-portrayal your answer to the Holden Caulfield idea, “It’s funny. All you have to do is say something nobody understands and they’ll do practically anything you want them to”?

Rakoff: Well, I definitely didn’t have that in mind when I was establishing the tone for the book. I came upon the tone in just a kind of instinctual happenstance way. I signed onto write this book with great trepidation. I’m not really a writer of memoir. I don’t write that much about myself. I’m also not a person who’s confessional in spirit. I don’t post on Facebook saying how sad I am. Anything like that. And in my fiction, I don’t even usually write in the first person. And so when I sat down to write the book, I found myself extraordinarily at sea, unsure of what this persona, this person, was. This voice that I needed to create.

Correspondent: Hence the “I am,” “I do,” “It is”? It’s kind of the early formation of “Well, how am I going to portray the Joanna on the page?”

Rakoff: Well, you know, it more came to me from the opening scene of the book in which you see it written almost as a “we.” And you kind of see vast numbers of young women going to work as assistants. And in writing that scene, I was able to kind of hit upon what I thought of as a tone that felt right to me for a book about things that took place at this point almost twenty years ago. More like fourteen, fifteen years ago when I was writing it. I wanted a tone that was not nostalgic. I thought that it would be very easy to slip into a kind of nostalgia for a bygone era. And so writing that scene that’s not purely about me, that kind of pans out and shows you lots of women who are doing the same thing that I was, like it’s a very sort of female role, this assistant’s role, allowed me to kind of hit upon this cool tone. And then I could slip into the kind of “I” of the book. In terms of the “I can,” “I am,” “I understand,” I will say that that is simply how I actually speak.

Correspondent: You do.

Rakoff: And I do tend to be a person who speaks in sentences…

Correspondent: You don’t like using “yes” or “yeah, man” or anything like that? That’s just not in your vernacular.

Rakoff: No. I do not. I will say that this is partly my parents’ fault. My parents are sort of two generations removed from me. They had me very late in life. They’re Depression era, Greatest Generation people. And they don’t use any slang. My mother’s letters to me are written as if she’s Emily Dickinson or Miss Manners. There are contractions, but there’s no slang used in my household. And certainly if I used anything that was grammatically incorrect or that fell into the realm of “of the moment” slang, if I said “Awesome!” in the ’80s, I was given a fisheye by my mom or I was told…

Correspondent: You stood in the corner with Fowler, basically reciting the rules of usage.

Rakoff: Kind of. It just was frowned upon. And without realizing it, I just sort of absorbed their grammatical constructs.

Correspondent: Well, how do you permit slang in your life now? Or even in your fiction? Or even in your memoir?

Rakoff: Well, in fiction and in memoir as well, I’m a huge stickler for dialogue. You may know this, but I spent many, many years primarily working as a book critic and one of the things that drove me crazy when I read contemporary fiction was dialogue that felt inauthentic. I remember reading a book in which nobody used contractions in the dialogue and I thought, “Why didn’t this writer read the dialogue out loud? This is absurd. Nobody actually talks like this.”

Correspondent: You haven’t actually gone to Contraction Central, this city out in West Virginia, where nobody actually…

Rakoff: Yes. I don’t want to go there. I don’t want to go to that place.

Correspondent: Yeah. They banned contractions. It’s been on the municipal ordinance for about twenty years now.

Rakoff: That may also be like the place where all bad literary translations go.

Correspondent: And cheap Dostoevsky translations in particular.

Rakoff: Yes.

Correspondent: All the Russians. Anyway, sorry.

Rakoff: I just actually read a novel in translation that is this novel that was a huge bestseller in France called The Yellow Eyes of Crocodiles.

Correspondent: Oh yeah.

Rakoff: And it’s been published all over the world. And it’s a very commercial novel. But the translation — I hope I’m not going to offend anyone listening to this — but the translation was clearly done in a very rapid way.

Correspondent: As about 80% of translations are. Because the translators are paid almost nothing.

Rakoff: Yeah. But I think this is because it was a bestseller and they wanted to get it out. And the language.

Correspondent: Much like Stieg Larsson.

Rakoff: The dialogue feels just absurd in it. Like I know these people are French, but nobody would talk like this. Like this is ridiculous. So anyway in my dialogue, I of course allow people to use slang. Because the dialogue comes out of the character. So it would be crazy to have all of my characters speak in the way that I do or address themselves in the way that I do. And I do as an adult…

Correspondent: As an adult, I will not speak slang? Is that what it is?

Rakoff: No. As an adult, I think that I find myself using slang ironically and saying things that I wouldn’t say as a teenager. Like saying, “That’s cool” or “That’s cute.” I banned the word “cute” from my lexicon for a long time and, an hour ago, I just described something as cute. Or I’ll say “Awesome!” to my kids.

Correspondent: Wow. You’re more orthodox than me. I have no problem with slang. But I do have a problem with things like “Because so and so.” That drives me nuts. And I can’t bring myself to say it, except in irony, which is kind of missing the point, I suppose. We’ve strayed quite a bit and I want to get back to the life you depict or the Joanna persona you depict on the page. You knew nothing of snow days. You knew nothing of jobs. You knew nothing of agents. You knew nothing of publishing. Of how much sandwiches cost. Of how much tax was taken from your paycheck. There’s one astonishing revelation midway through the book about unexpected student loans. This leads me to ask, especially in light of you kind of talking about your parents a little bit, how did you manage to delay learning about the responsibilities of life for so long?

Rakoff: Well, I was only 23 when this book takes place. So I don’t think I delayed them so long. I mean, I actually think — first of all, I think, and I guess I’ll say for people listening, this book takes place over the year that I was 23 and turned 24.

Correspondent: 1996.

Rakoff: Yes. And chronicles my first job, which was at…um…

Correspondent: The Agency.

Rakoff: A very storied agency. One of the oldest agencies. The second oldest agency in New York.

Correspondent: If you mention the first agency, they will strike you dead in the street. I think that’s the New York Publishing Codex. But anyway.

Rakoff: There’s contention about which is the oldest. Because literary agencies, when they first came into existence in the ’20s…

Correspondent: Blood feuds have been drawn over this question.

Rakoff: They were less established things. They were just kind of like a guy selling someone’s literary rights. So it’s not quite clear which of the two is the oldest. Regardless, I was 23. I had gone to college. I spent a year in grad school. And then I took this job. I think that the sort of arc that I’m describing in the book is actually relatively normal. A lot of my friends were going through the same thing. They had grown up, many of them in coddled affluent suburbs or perhaps the sort of coddled upper middle-class echelons of New York City or L.A. or places like that. And their parents had essentially provided for them. And in moving to New York, especially, more so than other cities. So at this time, friends of mine were moving to Prague and Seattle and Portland and Chicago, where there was a lot of music and also comedy happening. And they had a slightly easier time. But those of us who moved to New York, I think, were unprepared for the kind of economic realities of the city. And many of my friends really struggled. I think they sort of believed that they could move to the city and survive as actors, writers, dancers, or what have you. But this was not the New York City of a James Baldwin novel or the New York City of, I don’t know, my parents, where you could rent an apartment on Mulberry Street for $30 a month. And this was 1996. We were at the end of a big recession. It was almost the worst time to be a young person in New York. I mean, it just keeps getting worse and worse. So we were at the end of this terrible reception. So there was a sort of dearth of jobs. And yet at the same time, we were at the beginning of the dot com boom. So there was all this influx of cash and all of these people moving to start dot coms in Silicon Alley and what have you. So you have these kind of wealthier people moving in and real estate sort of going up and up as it always does. But this was a particular moment where things were quite difficult.

Correspondent: But you’re saying this in the “we” as opposed to the “I.” What about you, Joanna? What did you do to adapt to this new reality? Especially — and I don’t want to give too much away — because it seems to me that your parents had a very controlling hand in how you learned about life and you really had to resist in actually leaving and figuring out what it was to be an adult.

Rakoff: Um. Sort of. So I’ll just explain a little bit about the book. So before the book begins, I had been sort of de facto engaged. My college boyfriend, who was wonderful and, always, my parents loved him and my whole family loved him. He was about to start a doctoral program in Berkeley. And it was just assumed that I was going to move out there. And he had found an apartment for us. And I would find some sort of job. I had just finished a master’s in English, but that’s another way of saying that I had dropped out of a Ph.D. program. Because I became disillusioned with academia. So I was essentially — in other words, I was on a semi-path. Like I was going to marry this person who was wonderful and always and also accepted by my family, from a very similar background to me. It was just — everyone sort of assumed that I would finish my Ph.D. maybe at Berkeley or somewhere nearby. A lot of my family was in this area. They presumed I would settle down there. We would both get academic jobs and have children. And there was something in me that — and because my parents supported this, they were somewhat generous of me financially. Because this is what they wanted me to do. And I then, where the book begins, basically I had veered from this path. I essentially went out to Berkeley to see the apartment, figure things out. And then I was supposed to go back home and just get my stuff and come and live there permanently. And I went back to New York and essentially lived like a 23-year-old. I went out every night. I went to parties. I saw all my college and high school friends. They were all there. And I somehow fell into a job working as a PA on a Barbara Streisand film.

Correspondent: Really?

Rakoff: Yes.

Correspondent: Which one was it?

Rakoff: The Mirror Has Two Faces.

Correspondent: Oh, that one.

Rakoff: I’ve still never seen it.

Correspondent: I never saw it either. With Jeff Bridges. Yeah.

Rakoff: Yes. And it was filmed at Columbia and so a lot of my friends were at film school at Columbia and one of them said, “Hey, do you want to work as a PA on this film?” I said, “Sure.” So this seemed like such a weird and cool opportunity that I was able to say to my college boyfriend, “You know, I’m going to do this and then I’ll come out to you.” And then when that ended, I somehow fell into — in short, I fell into this job at the Agency. And that seemed like such a great opportunity. I said, “I got this job. I’m just going to stay for a little bit and try it out.” I very nervously said this to him. In other words, I went through a kind of almost — a little bit of the kind of rebellion that kids often go through when they’re adolescent. And I had never done anything like this. I had been the rule-following perfect student, obedient, devoted to family sort of kid. And so somehow my family — I don’t want to say that my family was oppressive. Because that’s absolutely inaccurate. They were not. But they sort of had just a very strong, defined sense of how a person should live in the world. And perhaps because they were of this older generation, they had a more conservative approach to life, where lots of my friends’ parents were more children of the ’60s and ’70s and were like “Do whatever you want! Be a writer!” Whereas my parents were like, “You need to go to law school.” They were more sort of a…

Correspondent: Have a career.

Rakoff: Be a doctor.

Correspondent: Be solid. Own property. That kind of thing.

Rakoff: Yes. Exactly. And really this was very different than most of my friends’ parents. So…

Correspondent: So wait. So where did this rebellious spirit, where did this come from? I mean, did you feel that you could sort of figure out what you wanted to do through publishing after you had done the academic racket? Or something like that?

Rakoff: Well, as I said, I really fell into that. I didn’t have any desire to work in publishing. I didn’t think, “I want to work in publishing!” I had my senior year in college as a sort of backup plan. I had interviewed just with the HR department at Random House and it was such an unpleasant experience that I thought, “I never — I don’t want to do this actually.” Like the career services people at Oberlin set it up for me. And I had to go into their corporate office in this ill-fitting suit. And I just hated the whole thing. But the agency was a whole different story. Because Random House is an enormous corporation who is now my publisher actually, ironically, and I was not really suited to working in a corporate environment, which is not my mentality. But the agency was this smaller, tiny institution. It felt like working in someone’s home. And it turned out that I was really suited to it. It was fun. It was interesting. It was actually literary. It wasn’t just about bottom line. I got to work with the estates of these sort of exciting authors. And so anyway I wasn’t trying to rebel through publishing. But I was — my parents did consider this a very strange and rebellious thing to do. They really did. And they felt like, “Oh my goodness! You went to this.” At the time, Oberlin was I think like one of the top five colleges in the country and I got like an almost perfect score on my SATs. I was like that.

Correspondent: You put this off as long as you could. And then finally, all right, it’s time to strike out.

Rakoff: Yes. they just thought it was crazy. Like “You could have gone to law school. You could have done anything. Why are you doing this? You’re making so little money.” And…and…

Correspondent: But the sense I got, at least as you portrayed yourself in the book, is that you almost kind of fell into this. Because the one thing I really actually enjoy, especially in the early part, is how you sort of say, “Well, I didn’t really know money. Yes, there were books. Plentiful books. I didn’t realize I bought so much.” That you weren’t really keeping tabs of how much things cost, how things broke down, how much of your paycheck was going to go into rent and expenses and so forth. But at the same time, that kind of amorphousness, that kind of ambiguity actually ended up working out for you. Simply by showing up to your job on the first day when it’s a snow day. You know?

Rakoff: Well, in terms of the financial stuff, it was sort of a mixed bag. My parents — here again, just to give a little context — my father’s a first generation American. His parents, as children, had escaped the pogroms and come to the U.S. My mother, her family had been in the States for a bit longer. But they were from that kind of unstable immigrant background and their priority as adults was the setting up of a stable home life and protecting me and my siblings from the kind of instability. My mother had been raised by a single mother. She had to live with various aunts and uncles being shunted from home to home. She had a very unstable upbringing. And, you know, never enough money. And I saw at the time and I really, really see now, now that I have my own kids, that they wanted to protect me from that perhaps. And they wanted to protect me — also there had been a lot of tragedy in my family. They wanted to protect me from the world in a way.

Correspondent: But I think it was in your genotype. Because your father actually was an actor before he was a dentist, as you point out in the book.

Rakoff: Yes.

Correspondent: And he was a dentist who liked to tell jokes. So definitely that strain was certainly in the Rakoff makeup, I think.

Rakoff: Do you mean the sort of artistic strain?

Correspondent: The artistic. The want to be sort of exuberant in some sense. At least, I’m basing this, of course, off the book and off of the last time we met. But I think it was there.

Rakoff: Yeah. It’s true. And there was this kind of ambivalence, I mean in terms of like my career stuff. My father, when I was a child, actually really encouraged me to be an actor myself. I was constantly told that I was a good actor and that I had talent. And so I did sort of veer in that direction. And then my mother would freak out and kind of pull me back in. My dad was much more sort of tolerant of these things. But it was a bit schizophrenic, to use the term loosely. Like he would encourage my more artistic creative things and then he would pull back and say, “Why don’t you go to law school?” He couldn’t figure out what he wanted. And there was also very possibly a little bit of annoyance and resentment with the kind of privilege that I’d been born into. Because as I said, he’d grown up during the Depression, starting off in a tenement apartment where his bedroom was like a curtained off area behind his father’s dental office. So I think that there was a little bit of that, that he felt like, “Augh! You think that you can just do…” — there’s this scene in the book where he kind of says this to me — “…you think you can just do whatever you want, but you really need to face the realities of life.” And I didn’t even understand what that was, purely because he and my mother had been so protective. And I had never seen a bill. I had never heard any concern about money. Anything. We weren’t incredibly wealthy, but my mother earned multiple fur coats. We traveled all over the world. My parents always said to me, “You’re a kid who never asked for anything. You never asked for toys.” But if I did, there was never a problem with getting it.

Correspondent: But there’s also this impulse to conceal how you were learning to live in New York with this guy named Don, this boyfriend in this apartment who you didn’t really tell them about. Simultaneously, they’re being, as I alluded earlier, very controlling in terms of signing you up for a student loan without actually informing you and not being clear about the costs. So how do you divagate through that particular friction? I mean, you want to be who you are. You want to actually, I think, learn how to do things. You do say, “I do.” And you do do things. But at the same time, you have to make mistakes. How do you deal with this with this family dynamic?

Rakoff: I mean, I guess I’m not sure what you’re asking me.

Correspondent: How do you find yourself when you are dealing on one hand with having to conceal things from your parents while simultaneously having to kind of stave off the “Well, we’re taking care of everything. You should live with us and get up for work two hours early for the two hour commute”? Do you know what I mean? That kind of thing.

Rakoff: Yeah. Well, I mean, I suppose that’s why I rebelled in the way that I did in a kind of stealth way. Like, you know, I don’t know. Doing lots of drugs in their living room or I don’t even know what. I sort of rebelled in the kind of A student who’s secretly doing drugs in the bathroom way, although I didn’t do drugs in the bathroom. I took this job that, in New York parlance, was a glamour job and that they could, if they really wanted to, they could talk to their friends about it. And it seemed like a respectable thing to do. And it had its own career path. And I lived in Williamsburg, where we are right now, which they thought was weird but it wasn’t so where I was living in a squat with a bunch of unwashed, dreadlocked drug addicts or whatever. You know, so it was definitely clear that they disapproved of things. But I just kept a lot from them. And that was sort of my way of rebelling, was withholding from them, whereas before, when I was a kid, I definitely considered my parents my best friends. I was a really unpopular, dorky kid. And I loved my parents and sort of told them everything. But when I got older, I realized at that point — that was when I realized in order for me to live the life that I want, I have to withhold from them. I have to keep things closer to the bone. And still my mother complains about this to me. I mean, I’ll hear her talking to a friend and she’ll say, “Joanna keeps things close to the bone.” That’s her term.

(Photo: Jared Leeds)

The Bat Segundo Show #547: Joanna Rakoff (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced