Steve Erickson appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #447. He is most recently the author of These Dreams of You. He previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #180.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Contriving plans to join a community of one half.

Author: Steve Erickson)

Subjects Discussed: Writing a novel around short bursts, plagiarizing the future, The Sea Came In at Midnight, the novel as kaleidoscope, rationale that emerges midway through writing a novel, losing 50 pages in These Dreams of You, not writing from notes, Zan’s tendency to hear profane words from telephone conversations, the considerable downside and formality of being dunned, fake politeness and underlying tones of contempt, not naming Obama, Kennedy, or David Bowie, Molly Bloom in Ulysses and Molly in These Dreams of You, Erickson’s commitment to the ineffable, letting a reader find her own meaning, defining a character in terms of story instead of public and historical terms, listening to David Bowie to get a sense of Berlin, Erickson’s cherrypicked version of Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy, not capitalizing American and European throughout Dreams, using autobiographical details for fiction, Jeanette Winterson’s Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, “part fact part fiction is what life is,” dating a Stalinist, why fiction is more informed by real life, how invented details encourage a conspiracy, the dissipating honor of being true to what is true, the last refuge of a bad writer, what a four-year-old can and cannot say, bending the truth when it sounds too fictional, Kony and Mike Daisey, combating the needs for believability and readers who feel defrauded, authenticity within lies, kids and photos who disappear in Dreams, striking a balance between the believable and the phantasmagorical, fiction which confounds public marketeers from the outset, postmodernism’s shift to something not cool, limitations and literary possibilities, the burdens of taxonomy, living in a culture that wishes to pigeonhole, why Zeroville and These Dreams of You gravitate more toward traditional narrative, reviewers who are hostile to anything remotely unconventional, writing a novel from the collective national moment, the relationship between history and fiction, being a man “out of time,” thoughts on how a private and antisocial reading culture is increasingly socialized, having an antisocial temperament, writers who cannot remember the passages that they write, the pros and cons of book conventions, and being “a community of one.”

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Erickson: We do live in a culture that wants to pigeonhole things. I don’t know whether that’s a function of late 20th century/early 21st century culture or is a function of American culture, or some combination of the two. In Japan, for instance, they don’t seem to worry about that when it comes to my novels.

Correspondent: But with Zeroville and with Dreams, we have moved a little bit more toward traditional narrative. I mean, maybe the impulse was always there. But do you think this has just been symptomatic of what you’ve been more occupied with of late? Fusing that traditional narrative with, say, some of these additional ideas of disappearance, of inserting words into sentences, and so forth?

Erickson: Right. Well, it’s hard for me to know. There are still a lot of people out there who would read this novel, These Dreams of You, and think it’s a pretty damn unconventional novel. They may not have read Our Ecstatic Days and thereby see this novel as whatever you want to call it: more accessible. But I can tell from the reviews I’ve gotten on this novel, which have largely been somewhere between good and better than good, nonetheless there are reviewers out there who really don’t quite know what to make of even this particular novel, which I think you’ve rightly said steers a little bit toward the conventional than earlier novels. And in the case of Zeroville, again, I had a strategy from the beginning, having thought about this novel for a while. I had started the novel at one point and I was writing it differently. And I was writing it — I don’t mean differently in terms of my earlier books. It was written more like my earlier books. And I stopped. I threw it out. Because I felt that this novel is about loving the movies, being obsessed with movies. It should have some of the energy of a movie. It should follow some of the narrative laws of a movie. So you had a lot of dialogue and a lot of the story being told in external terms. Being told in dialogue. Being told in action. Not a lot of motivational stuff. The main character in that novel, we never quite know where he’s coming from. We never know if he’s some kind of savant, or socially and mentally challenged. We never know.

In the case of this novel, I was aware at some point that, first of all, I was writing a story about a family, which I had never done. And, secondly, I was writing a story that it became clear to me, really from the first scene, that addressed the national moment and a moment that any reader could recognize in a way that none of my other novels quite had. Los Angeles was not submerged in a lake or covered by a sandstorm. It was out of that opening scene of the novel, which was the real-life scene that led to writing the novel. I merged a story that I thought would be recognizable to most readers. And I didn’t want to completely lose that. There are a lot of times in the novel that I think that is challenged. That recognizability. Or that recognition rather of the contemporary moment. Halfway through the book, the story suddenly changes track. But even as I was taking the reader, even as three quarters of the way through the book I knew the reader was going to be saying “Where is this thing going?” I didn’t want to lose that connection between the book and a moment of national history. It’s a history that’s still going on. It’s not a history of the past, but of the present. I didn’t want to lose that connection.

Correspondent: But why did you feel at this point, with this novel, that you needed to respond to the national moment? I mean, history is something, especially as it is unfolding, that one doesn’t necessarily feel obliged to respond to. So now you’re getting into questions of, well, is it possible that you are giving into the reader somewhat? In light of the conditions that we were describing earlier. Where did this need to respond to the 2008 climate come from?

Erickson: Well, I think it was completely personal. I was sitting on the sofa watching the election in November 2008 — Election Night — with my black daughter. And I knew this was a singular moment for me. And I knew this was a singular moment for her. And it was a singular moment for the country. And it was one of those cases where the story made itself manifest to the point of screaming at me. Here’s a story that not many other people are in a position to tell, given the circumstances of their lives as those circumstances were coinciding with the circumstances of the country.

Correspondent: Sure. I wanted to actually go back into the intertextuality within the novel. You have this character — J. Willkie Brown, the Brit who invites Zan over to give the lecture on “The Novel as a Literary Form Facing Obsolescence in the Twenty-First Century, Or the Evolution of Pure History to Fiction.” Now if we call journalism the first draft of history, it’s interesting that you also describe that “Zan’s single triumph over Brown is that, in time-honored journalistic tradition, the world-famous journalist always longed to write a novel.” It’s also interesting that Zan must return to his American roots: the original British origin point, right? To collect his thoughts on how he has dealt with words. And I’m wondering how much this relationship between history and pure fiction is predicated on Anglo-American relations. Can any novel or any life entirely deflect “the crusade against gray” that you mention?

Erickson: The crusade against what?

Correspondent: The crusade against gray. It’s when you’re describing Ronnie Jack Flowers and the specific content of his views. I wanted to talk about him, if it’s possible too.

Erickson: Yeah. That’s a big question. Early on, Zan wonders — or actually an omniscient narrator wonders by way of Zan — if this is the sort of history that puts novelists out of business. And I’m not sure I’ve got a sweeping cultural answer for all this. At some point early on in my life, well before the 21st century, I knew that I was a man out of time. I knew that the great art form of the 20th century was film. And I still believe that. And at the same time, popular music was rendering other media obsolete or, in terms of relevance, was usurping all of these other forms. But my talent and my temperament is to write novels. You know, and I should probably have been born fifty years earlier. And so as much as I would love to convince myself that I am operating in the central cultural arena of the time, I know I’m not. I know that fiction becomes not a fringe form, because too many people still read. And not even a secondary form. But a form that becomes more private. That is not shared with the culture at large. I mean, people read novels in private. Whereas they still tend to watch movies in public. Even as we watch more and more movies by ourselves at home. Even as they tend to respond still to music in public, whether they’re in the car with their sound system. So it’s just…it’s what I do. And it’s what I’m stuck doing. And the relevance or significance of fiction in relationship to history or journalism is almost beside the point for someone like me.

Correspondent: So working in a cultural medium that is below the mass culture omnipresence is the best way for you to negotiate these issues of history and fact?

Erickson: Well, I think…

Correspondent: A more dignified way?

Erickson: No, I think, Ed, it’s the only way I know. That’s all. I don’t know that it’s the best way or the more dignified way. I mean, I can’t rationalize it in those terms. In a way, I would like to be able to. You know, at some point early on, I thought a lot about filmmaking. When I was in college, I was actually a film student.

Correspondent: Yes.

Erickson: But I recognized at some point that, for better or worse, whatever talent I had — I felt I had some talent writing fiction. I had no idea whether I’d have any talent making movies. But perhaps even more importantly, temperamentally fiction is the province of a loner. Fiction is about locking yourself up in a room and having as little social interaction with other people as possible, and living in this world that you’ve created. There is nothing collaborative about it in the way that film is, or even making music is. So the answer to your question is entirely personal. It’s entirely personal. It’s what I was just meant to do.

Correspondent: You just have an anti-collaborative temperament.

Erickson: Absolutely I do. I mean, it’s more than that. I have an antisocial temperament. I teach in a writing program back in California and I have a lot of problems, actually, with writing programs and writing workshops. And I tell my students this. I say, the thing is, the paradox is that a writing program socializes what is really an antisocial endeavor. There’s something very strange about shutting yourself off from the rest of society to create this world or reality that’s completely yours and that you don’t share with anybody until it’s done, and even then you share it on a very private basis. If someone’s sitting across the room, and they’re reading one of my novels, I’m going to leave. You know, I don’t want to be there. Because even though I know that the public has complete access, what I did still remains so private to me, I don’t want to be around when somebody’s reading my work. Except for cases like this, I don’t especially want to have casual conversations about it. Perhaps strangest of all, and I’ve heard a number of other writers say this — I heard Jonathan Lethem say it a few weeks ago — people will come up to me, for instance, and ask me about a section of a book and I have no recollection of what they’re talking about. I have no recollection of writing it. I have no recollection of what I was thinking when I wrote it. I often have to ask them to show me what it is. Because I was utterly immersed in that, and then it’s done, and I need to leave it behind.

Correspondent: Running away from people who are reading your books. I mean, does this create any problems for you to go about your life? If you’re interested in the types of things that Steve Erickson readers are likely to be interested in, this could create some intriguing social problems.

Erickson: Well, as uncomfortable as it may make me to be in the same room, I would love to tell you that my life is littered with scenes of people reading my books everywhere I go. But that’s not the case. So it doesn’t happen that often. But I don’t have a lot of conversations with people who are casual friends about my work. And I don’t want to. So in that sense, the antisociability — is that the right word for it? The antisociability of the writing and the work, it does go on. It bleeds outside the lines of the life of that work, and it bleeds into areas of my other life, where I don’t, even though I’m always a writer, I don’t want to be interacting with people as a writer.

Correspondent: So is there any place for community? An increasing term used, I find, in writing. We have a “literary community” and so forth. Is this a logical extension of what some people find in, say, AWP or MFA workshops? Is there any possible place for community for you? Or that you find of value?

Erickson: For me, not especially. For other writers, perhaps. And I’ve been to AWP. And I’ve been to book conventions. The LA Times Festival of Books. And I can even drive a certain amount of pleasure for 24 hours to meet other writers. But the only community that gets any writing done is a community of one. And at the point that it becomes too much a salon, then I check out of it.

Correspondent: So for you, being antisocial is the truest temperament for an artistic writer.

Erickson: Well, I don’t know how you can be anything else. Certainly at the moment that when you’re doing the work. For me, that’s true, yeah. I can’t speak for other writers.

(Photo: Stefano Paltera)

The Bat Segundo Show #447: Steve Erickson (Download MP3)

Correspondent: Let’s get into this. You point out that George McGovern is one of the key figures responsible for Democratic timidity in relation to the sexual counterrevolution. You suggest that McGovern losing his temper, telling a voter to kiss his ass — that was one factor. The really terrible decision he made involving ordering milk with a liver sandwich in a Jewish deli. Not exactly the smartest choice. There was also this idea that McGovern, because he encompassed this cultural radicalism and failed, that this was what encouraged the Democrats to backpedal. So I’m wondering to what degree is this political temperament and to what degree is this, I suppose, a cultural radicalism that Democrats are afraid of? I mean, 2004, you have Howard Dean’s famous scream. And even before that, everybody was like, “Wow, this guy’s finally standing up for progressivism.” I mean, it seems to me that if you have a situation where the Democratic presidential candidates are limited in what they can say and how they can act, that this kind of progressive idea of, say, supporting something like the Equal Rights Amendment, you’re almost not allowed to do that. So how did this state come to be and what solutions do we have for the future?

Correspondent: Let’s get into this. You point out that George McGovern is one of the key figures responsible for Democratic timidity in relation to the sexual counterrevolution. You suggest that McGovern losing his temper, telling a voter to kiss his ass — that was one factor. The really terrible decision he made involving ordering milk with a liver sandwich in a Jewish deli. Not exactly the smartest choice. There was also this idea that McGovern, because he encompassed this cultural radicalism and failed, that this was what encouraged the Democrats to backpedal. So I’m wondering to what degree is this political temperament and to what degree is this, I suppose, a cultural radicalism that Democrats are afraid of? I mean, 2004, you have Howard Dean’s famous scream. And even before that, everybody was like, “Wow, this guy’s finally standing up for progressivism.” I mean, it seems to me that if you have a situation where the Democratic presidential candidates are limited in what they can say and how they can act, that this kind of progressive idea of, say, supporting something like the Equal Rights Amendment, you’re almost not allowed to do that. So how did this state come to be and what solutions do we have for the future?

Anderson: If we can just get a little bit more of our own buying power to be recycled in our own communities, maybe we can bring those jobs numbers up. The other number is that black businesses are, by far, the greatest private employer of black people. Black unemployment, we know, is three times the national average of our white counterparts. Highest among any ethnic group. And in some places like Birmingham and Cleveland, we’re at black unemployment like 15, 16%. So maybe if we start supporting more black businesses that employ black people, we can stop black unemployment. So it was really just about making sure the conversation about the black situation in America is thorough and comprehensive. We can’t just keep talking about black unemployment and then not talk about black buying power and the fact that black businesses employ people and that none of our buying power is going to black businesses. So the numbers that we depended on — to get back to your question — you know, it’s just kind of known in our community how we don’t support each other. How if you walk up and down the street in a black neighborhood, none of the businesses there are black-owned except for funeral parlors, barber shops, and the braid salons. It’s just kind of known that most of the products on the shelves, none of the retailers in our community, none of the franchises are black. So we just kind of know that and joke about it. It hurts, but we just accept it. But it’s so hard to find data to bear that out. My roommate jokes about it. But we did find an interesting study — I think it was an economist, John Wray. Who did a study based out of DC that proved this horrible statistic about how long the dollar lives in different ethnic communities.* This statistic is used a lot in this conversation when people

Anderson: If we can just get a little bit more of our own buying power to be recycled in our own communities, maybe we can bring those jobs numbers up. The other number is that black businesses are, by far, the greatest private employer of black people. Black unemployment, we know, is three times the national average of our white counterparts. Highest among any ethnic group. And in some places like Birmingham and Cleveland, we’re at black unemployment like 15, 16%. So maybe if we start supporting more black businesses that employ black people, we can stop black unemployment. So it was really just about making sure the conversation about the black situation in America is thorough and comprehensive. We can’t just keep talking about black unemployment and then not talk about black buying power and the fact that black businesses employ people and that none of our buying power is going to black businesses. So the numbers that we depended on — to get back to your question — you know, it’s just kind of known in our community how we don’t support each other. How if you walk up and down the street in a black neighborhood, none of the businesses there are black-owned except for funeral parlors, barber shops, and the braid salons. It’s just kind of known that most of the products on the shelves, none of the retailers in our community, none of the franchises are black. So we just kind of know that and joke about it. It hurts, but we just accept it. But it’s so hard to find data to bear that out. My roommate jokes about it. But we did find an interesting study — I think it was an economist, John Wray. Who did a study based out of DC that proved this horrible statistic about how long the dollar lives in different ethnic communities.* This statistic is used a lot in this conversation when people  Correspondent: I know. No, this is all very good. And there’s a load of threads to start from here. Actually, I’m sure you’re familiar —

Correspondent: I know. No, this is all very good. And there’s a load of threads to start from here. Actually, I’m sure you’re familiar —  Anderson: The white man Charlie. But anyway, the book is really — if I’m yelling at anyone, it’s at black consumers. Because there’s a lot of history here that contributes to the bad situation we’re in. I’ll be really quick. A lot of it has to do with integration. Of course, we love what integration did in this country. Of course, we fought for it. But it had some really negative impact. Some deleterious impact into the black economy, if you will. Because we’re forced to, because we’re segregated, we built up our own businesses. We had a strong sense of entrepreneurship in our community. And we recycled our wealth. So that was just the fact. That was the way it was. And the University of Wisconsin

Anderson: The white man Charlie. But anyway, the book is really — if I’m yelling at anyone, it’s at black consumers. Because there’s a lot of history here that contributes to the bad situation we’re in. I’ll be really quick. A lot of it has to do with integration. Of course, we love what integration did in this country. Of course, we fought for it. But it had some really negative impact. Some deleterious impact into the black economy, if you will. Because we’re forced to, because we’re segregated, we built up our own businesses. We had a strong sense of entrepreneurship in our community. And we recycled our wealth. So that was just the fact. That was the way it was. And the University of Wisconsin  Anderson: Right. And this is a huge point that I have to contend with when I push this supply diversity franchise rediversity message into the community. And here’s how it goes when I’m talking to black folk who I’m trying to get to support black businesses. It should not be that tough of a fight, but it is. When I say this to them, they come at me, generally with stuff like “Well, we tried to Karriem [Beyah]’s grocery store. He didn’t have the thing that we wanted.” Or it wasn’t like going to our Jewel, the big grocery store chain around here. Or you can go to this black franchise. But I didn’t see a bunch of black employees there. Or how do I know Quiznos is a good franchise to be supporting? So I get a bit of a challenge. Then I say, “Well, you know what? How is that? I mean, what are you doing now?” Basically, we’re just out there supporting anybody. Not thinking about what the businesses are doing for us. Polo. I mean, Polo blew the lid off of black consumers. We have black Polo parties that we have for our kids. I mean, it’s just ridiculous how addicted we are to the Polo brand. I have nothing against Polo Ralph Lauren. But I did have a friend who works writing for the CFO of Polo, and I asked her to do some research for me. She’s a conscious consumer like me. HBS grad. Very well connected in the company. And she thinks they talked with the marketing folks, the procuring folks, everybody about buyer diversity. Do you do business? How do you invest in the black community? We have so much money coming in from the black community. And their answer to me was, “Well, our label comes out of Indonesia.” And it’s unbelievable. That’s the best we can do to reciprocate the loyalty that the black community’s giving you? So it’s like, “Yeah. Maybe.” And you’re totally right about the Quiznos thing. But the first answer to them is, “But you’re supporting Polo. And it’s not like you’re stopping in support of Polo.” And I’m not saying don’t support Polo. But if you’re so discriminating with how you spend your money, there’s a lot of things that we shouldn’t be doing that we ought to be doing.

Anderson: Right. And this is a huge point that I have to contend with when I push this supply diversity franchise rediversity message into the community. And here’s how it goes when I’m talking to black folk who I’m trying to get to support black businesses. It should not be that tough of a fight, but it is. When I say this to them, they come at me, generally with stuff like “Well, we tried to Karriem [Beyah]’s grocery store. He didn’t have the thing that we wanted.” Or it wasn’t like going to our Jewel, the big grocery store chain around here. Or you can go to this black franchise. But I didn’t see a bunch of black employees there. Or how do I know Quiznos is a good franchise to be supporting? So I get a bit of a challenge. Then I say, “Well, you know what? How is that? I mean, what are you doing now?” Basically, we’re just out there supporting anybody. Not thinking about what the businesses are doing for us. Polo. I mean, Polo blew the lid off of black consumers. We have black Polo parties that we have for our kids. I mean, it’s just ridiculous how addicted we are to the Polo brand. I have nothing against Polo Ralph Lauren. But I did have a friend who works writing for the CFO of Polo, and I asked her to do some research for me. She’s a conscious consumer like me. HBS grad. Very well connected in the company. And she thinks they talked with the marketing folks, the procuring folks, everybody about buyer diversity. Do you do business? How do you invest in the black community? We have so much money coming in from the black community. And their answer to me was, “Well, our label comes out of Indonesia.” And it’s unbelievable. That’s the best we can do to reciprocate the loyalty that the black community’s giving you? So it’s like, “Yeah. Maybe.” And you’re totally right about the Quiznos thing. But the first answer to them is, “But you’re supporting Polo. And it’s not like you’re stopping in support of Polo.” And I’m not saying don’t support Polo. But if you’re so discriminating with how you spend your money, there’s a lot of things that we shouldn’t be doing that we ought to be doing.

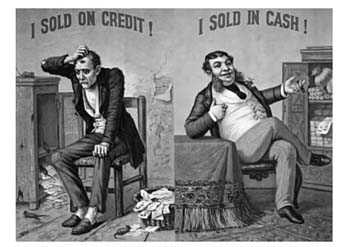

Correspondent: You start this book with a late 19th century image of the fat and prosperous man who sold in cash and the skinny man who sold on credit. I think that more than a century later, it’s safe to say that those roles have now been flip-flopped. You also write, “In the era of the CMO, the smart bank could be like the Skinny Man, its vaults nearly empty, with a pile of IOUs in a nearby basket.” I have to ask you, Louis. You are the debt man. Why were so many people willing to place their faith in the supernatural qualities of the collateralized mortgage obligation? Your book describes a Freddie Mac ad that appeared in a 1984 issue of the American Bankers Association Journal which contained magical gnomes. And they frightened me when I saw that picture.

Correspondent: You start this book with a late 19th century image of the fat and prosperous man who sold in cash and the skinny man who sold on credit. I think that more than a century later, it’s safe to say that those roles have now been flip-flopped. You also write, “In the era of the CMO, the smart bank could be like the Skinny Man, its vaults nearly empty, with a pile of IOUs in a nearby basket.” I have to ask you, Louis. You are the debt man. Why were so many people willing to place their faith in the supernatural qualities of the collateralized mortgage obligation? Your book describes a Freddie Mac ad that appeared in a 1984 issue of the American Bankers Association Journal which contained magical gnomes. And they frightened me when I saw that picture. Hyman: Exactly. So you need to understand that it used to be that it was very difficult to get loans in America of any kind. And that’s why I start the book off with that picture. Because the picture of the Skinny Man, who is nervous and afraid because he had lent on credit to his customers in his store. It was a picture that would be hung in a 19th century store. And the reason I start with that is because I think more than a graph, we are all besieged by numbers these days. More than a graph, it gets at the different mentality, the different practice of lending in the 19th century. That lending was something that was not profitable. It was something that in terms of cash loans wasn’t even legal. And yet today it’s the center of our capitalism. So how did that transformation happen?

Hyman: Exactly. So you need to understand that it used to be that it was very difficult to get loans in America of any kind. And that’s why I start the book off with that picture. Because the picture of the Skinny Man, who is nervous and afraid because he had lent on credit to his customers in his store. It was a picture that would be hung in a 19th century store. And the reason I start with that is because I think more than a graph, we are all besieged by numbers these days. More than a graph, it gets at the different mentality, the different practice of lending in the 19th century. That lending was something that was not profitable. It was something that in terms of cash loans wasn’t even legal. And yet today it’s the center of our capitalism. So how did that transformation happen?  Hyman: People forget. They forgive. And they think that it would be different this time. Because they were tradeable in the secondary market, which the ones in the 1920s were not. They were born toxic almost in the 1920s. But they thought, “Well, these will be fine. They’ll be like FHA loans.” Which had worked for several generations. And actually they worked fine. The securitization worked fine for a long time. From the mid-1970s on for about thirty years. They worked fine.

Hyman: People forget. They forgive. And they think that it would be different this time. Because they were tradeable in the secondary market, which the ones in the 1920s were not. They were born toxic almost in the 1920s. But they thought, “Well, these will be fine. They’ll be like FHA loans.” Which had worked for several generations. And actually they worked fine. The securitization worked fine for a long time. From the mid-1970s on for about thirty years. They worked fine.