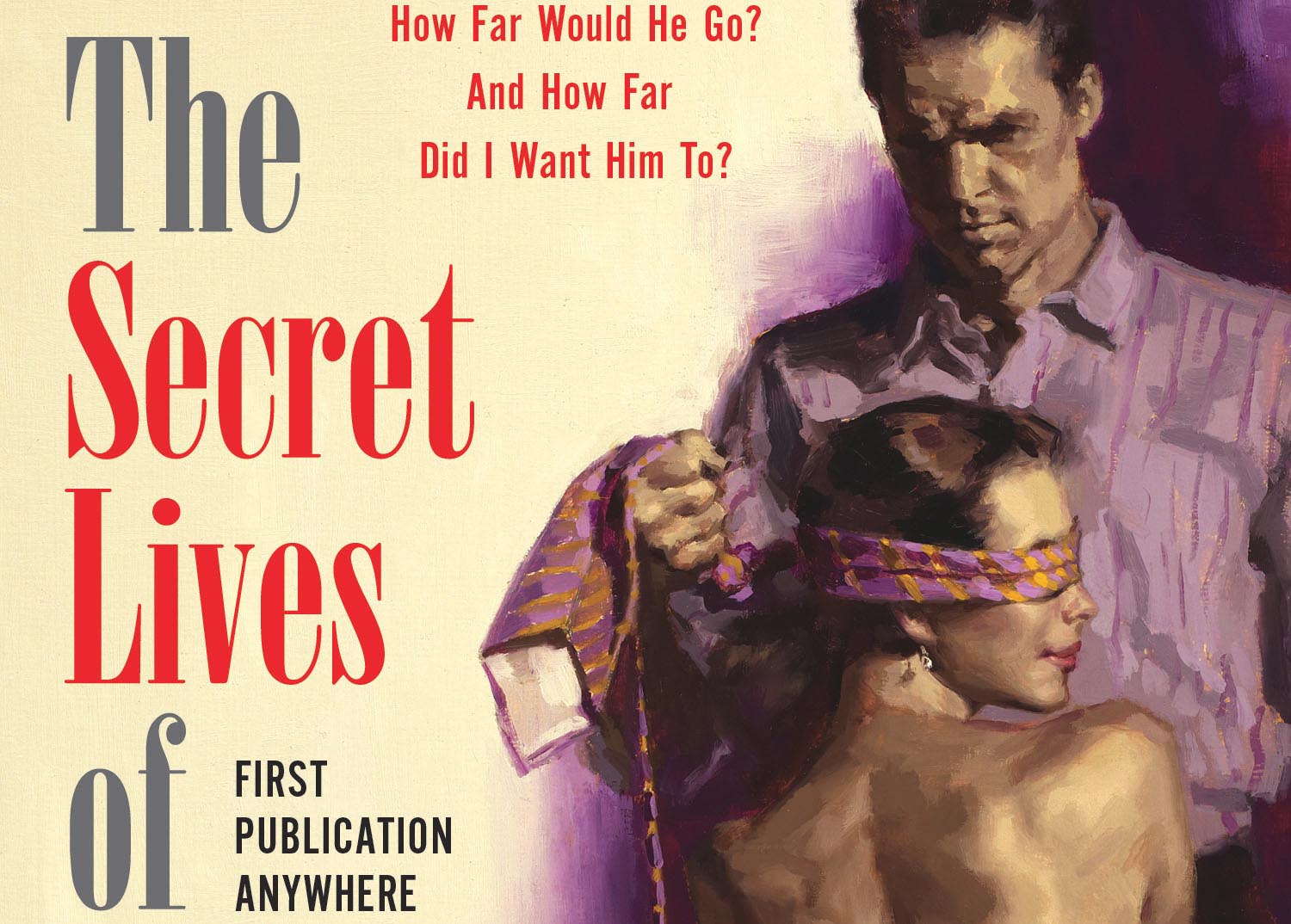

Elissa Wald is most recently the author of The Secret Lives of Married Women.

[PROGRAM NOTE: Halfway through this conversation, Our Correspondent, frustrated at getting minor details wrong about Elissa Wald’s novel and not establishing a sufficient rapport with Wald, packed up his gear and was prepared to leave, due to his incredibly high standards and his tendency to implicate and incriminate himself when these standards drop. Wald, to her great credit, persuaded Our Correspondent to stay. So in the second half, we describe what went wrong and we talk through it, finding a new area to chat without any notes or prerigged questions. We have aired the conversation in its entirety because it is important to be transparent about flaws as well as strengths.]

Author: Elissa Wald

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: Returning to New York after living here for eighteen years, Portland, having an accidental noir subconscious sense, expanding a 96 page story into a viable book without padding it out, meeting Charles Ardai, being influenced by Alice Munro, how Munro works a lifetime of material into a short piece, defying the “literary vs. genre” war, authors who use twists to advance narrative, Stephen King, why erotic fiction isn’t taken seriously, Meeting the Master, being beholden to the category whims of bookstore chains, the erotic qualities of reading something aloud, Hysterical Literature, Beautiful Agony, the mind and body relationship and implicating the reader, sexual intimacy at a distance of six feet, literal vs. enhanced intimacy, differing perceptions of soft porn, feelings of class affinity, an unanticipated two part interview format, how Wald first started writing, not being a good singer, passing notes in class as a storytelling medium, early BDSM fantasies, differing notions of slavery, Roots, addressing transgression, noir as a natural vehicle, growing up with non-mainstream longings, the Society for Creative Anachronism, having a radar for BDSM types, mental blue screens of death, the instinct to be drawn to libertine types, first becoming aware of your provocative nature, becoming aware of morality through being provocative, the 7 Most Controversial Erotic Novels, the importance of candor and giving something up, the many different ways to be married, accepting another person’s transgressions, exploring marital truths in fiction, when readers trust novelists on dangerous subjects, and sheer invention vs. fictitious moments that are closer to home.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I wanted to bring up Norman Mailer’s review of American Psycho in Vanity Fair in 1991. He was one of the first figures to defend that book. And he wrote, “Nowhere in American literature can one point to an inhumanity of the monied upon the afflicted equal to the following description.” And he proceeded to describe Patrick Bateman’s assault on the bum. Mailer also tied this in with Hannah Arendt’s notion of the banality of evil. But this is all very much in line with the first novella in your book, “Man Under the House,” because the treatment that Stas offers this laborer Jack hits many of the same notes. And it got me thinking, “Wow, we really don’t have this idea in fiction these days.” And I wanted to ask. In the last twenty-two years, why do you think American literature has not been especially concerned with this notion of class violence? To what degree were you aware of it? And did you hope to respond to it in any way?

Wald: Well, before we get to that, could you clarify what you mean by Stas’s treatment of the…

Correspondent: Of Jack?

Wald: Yes.

Correspondent: Well, in the sense that there seems to be this strange resentment. Not just in relation to obviously his wife, Leda, but also in relation to how he kind of resents the guy. There’s this moment where he is humiliated in Home Depot. So I picked up on this kind of class resentment that dictates Stas. And we can talk about how also it informs his past in Russia. Because he was indeed a handyman in his early days, as we learn in New York. But that notion of violence with this kind of class-to-class idea attached to it was something that was different and what I don’t usually see in fiction, which is one of the reasons why I wanted to talk with you. One of the reasons I wanted to get your answer on the subject.

Wald: That’s a fascinating question and I actually would not have thought about it that way at all. I don’t think Stas is drawing a distinction between himself and the workman on a class level. I think he just felt like this man is overly interested in my wife. I think he noticed that before the wife did, and that was what he was reacting to.

Correspondent: Even though we have this move from New York to Portland suburbia, where there’s the grand announcement, “Hey! I have a backyard.” And all this. I mean, none of that was really a concern of yours? Were you playing with some of the ideas of middle-class strivings or anything like that? Were you thinking about any of this?

Wald: Not consciously. No. I mean I can’t. People bring all kinds of interpretations to your work. And I never will say, “Oh, that’s not what it’s about.” Because I don’t know, you know? I can only say it’s not consciously what it’s about. It was nowhere in my mind.

Correspondent: Class was never a factor at all?

Wald: It wasn’t.

Correspondent: Wow.

Wald: It never crossed my mind.

Correspondent: What do you think — now that I’ve rambled quite a bit about it, why do you think that I got this particular reaction from it? I mean, were you ever concerned with any socioeconomics at all?

Wald: Well, I guess the one place where I can see what you’re saying maybe is that there’s a moment when Jack is literally under the house. He’s looking at the pipes. And she flashes on this picture of this proletariat wrestling. And so, yeah, I did say a member of the underworld bent on mutiny. So, yeah, this is what I mean. I’m not dismissing your interpretation. Just saying that I wasn’t consciously aware of it for much of the book.

Correspondent: So what interested you about exploring this dynamic with Jack and with Stas? What kept the conflict brewing as you were writing this?

Wald: Well, so interestingly, my husband and I decided to buy a house. There was a very attentive worker next door. And I spun the story into something so much more dramatic and involved than anything that really happened. But something that did happen early on was that my husband really didn’t like this guy right away. And I thought he was overreacting at first. And by the time I started to feel like this guy was overbearing, I didn’t want to tell my husband. And there were a few reasons for that. But one of them was that I thought that if I tell him, then there’s going to be a war. There’s going to be a war on some level. We just moved into this house. This guy is right next door. He’s essentially a neighbor for the time being. I don’t want an open war with this person. We just moved in. I don’t want this around my home. So I think most writers are to an extent a participant/observer in life. So they’re living their lives and they’re very much a participant. But there’s also, I think, a part of the writer’s mind that’s always observing. And so I thought, “Isn’t this interesting? I’m not only becoming nervous about this man. But I feel like he’s driving an emotional wedge between my husband and myself.” And that was fascinating. Even while it was wildly uncomfortable to experience it, it was still fascinating to the writer in me. And so I just took it from there and spun it.

Correspondent: Your husband isn’t Russian by chance?

Wald: He is.

Correspondent: He is! My goodness. So you were really drawing from reality.

Wald: So like a lot of writers — you know I know a lot of writers even give their protagonists their own names. But it’s still fiction. Like Philip Roth does that a lot. So I really do draw honestly from life a lot of the time and yet it’s unequivocally fiction. I make all kinds of stuff up. So it’s really a blur.

Correspondent: Do you have any legal background at all?

Wald: No. I did work for an attorney as an assistant.

Correspondent: Was he blind?

Wald: No. I did work for a blind man.

Correspondent: Oh, okay.

Wald: But he wasn’t a lawyer.

Correspondent: So the first part, interestingly enough, is truer to your life than the second part.

Wald: You know, I think everything’s true to my life on some level. I mean, I identify with all the characters on some level. All the female characters.

Correspondent: In the New York Times Book Review, I wanted to bring up Megan Abbott’s review. She wrote about your book. She brought up James M. Cain’s notion of the “love rack,” which involves finding a way to manipulate the readers into caring for criminal figures. The way into that, she said, is often through lust or desire. That’s how you get that vicarious solicitude for a scumbag. I’m wondering to what degree the idea of planting Leda in this suburban splendor or Lillian in this seemingly stable world, vocationally as an attorney, was kind of your 21st century answer to the love rack. I mean, was one of your goals to reach these vanilla middle-class readers or anything?

Wald: You know, interestingly, we talked a moment ago about how people bring their own interpretations. It was very amusing to me — I mean, Megan Abbott is a phenomenal writer. I appreciated her review deeply. But she imagined that it was a deep, deliberate bow to legendary noir author James M. Cain and I’ve never read a word of Cain in my life.

Correspondent: You have not!

Wald: Never. Not once. Never seen a film based on any of his books. Never given him a moment’s thought.

Correspondent: My goodness.

Wald: So that was interesting to me that she decided that.

Correspondent: Well, and I apparently have done the same thing. My goodness. I mean, have you read any books? (laughs)

Wald: Actually, I think it’s great that people bring their own interpretations. To me, that means it’s speaking directly to a reader’s experience and their frame of reference. So I don’t mind that people do that.

Correspondent: But actually I agree with Megan to a large degree. Because it does fulfill some of the relationship that books have to noir, while simultaneously also breaking from them. And this leads me to ask you. I mean, what kind of criminal fiction or noir have you soaked up? Or are you just basically living a noir life and that’s where it comes from?

Wald: I’ve read almost no noir in my entire life.

Correspondent: (laughs) Wow.

Wald: This is a new genre for me. I didn’t set out to write a crime novel. What happened was that Charles Ardai is a long-time friend of mine. Charles Ardai, the publisher of Hard Case Crime.

Correspondent: He’s great.

Wald: And I have sent him everything I’ve written for the last twenty-five years. Because he’s a great reader. He’s a great editor.

Correspondent: Yes.

Wald: And it never occurred to me ever that I would ever be a Hard Case author. Because I don’t write crime fiction.

Correspondent: Well you do now. (laughs)

Wald: And it’s been wonderful. So I sent him the manuscript, “Man Under the House.” It was just a long story. And I was aware that I was trying my hand at a psychological thriller. But it honestly hadn’t crossed my mind that it was also a crime story. I just hadn’t thought of it that way. So I was astonished when he said, “I want this for Hard Case.” But, no, this isn’t my genre. It’s never been my genre. I’ve read no crime writers. Scott Turow is the one thriller writer that I’ve read and loved.

(Loops for this program provided by mingote and ebaby8119.)

The Bat Segundo Show #528: Elissa Wald (Download MP3)

Correspondent: But this also leads me to go back to the question of the sandwich. I mean, I get that calories were new. They were in the air. People didn’t make any distinction between the calories one received from sugar and the calories one received from an apple. And there are a number of forms of advertisement you depict in this book that show that candy manufacturers played into this and used this to manipulate the public into buying more candy. But with things like the Chicken Dinner bar, I’m just absolutely curious about why something like that could be on the market for so long and yet you say that it’s lost to history. The taste. I mean, certainly there’s someone out there who knows about it and there’s someone out there who has a sense of how many of these sandwich-realted chocolate bars were actually eaten between the clock, so to speak.

Correspondent: But this also leads me to go back to the question of the sandwich. I mean, I get that calories were new. They were in the air. People didn’t make any distinction between the calories one received from sugar and the calories one received from an apple. And there are a number of forms of advertisement you depict in this book that show that candy manufacturers played into this and used this to manipulate the public into buying more candy. But with things like the Chicken Dinner bar, I’m just absolutely curious about why something like that could be on the market for so long and yet you say that it’s lost to history. The taste. I mean, certainly there’s someone out there who knows about it and there’s someone out there who has a sense of how many of these sandwich-realted chocolate bars were actually eaten between the clock, so to speak.