(Start from the Beginning: The Dead Writer)

(Previously: The Believers)

Nine months after the civil unrest in sixteen cities had been stubbed out (historians would later call this period the 2027 Pancake Riots because many of the protesters had doused bankers and Wall Street men in pancake batter, spawning an unanticipated costume trend the following Halloween in which kids bought third-hand business suits, dressed up as the rich, and trick-or-treated with gallons of pancake batter dumped over their heads), the Democrats — who controlled both the House and the Senate by a mere thread — had finally figured out, twenty years too late, that business-as-usual lip service and squeaky-clean centrism were probably not enough to hold the country together. They began welcoming more progressives into their wings, largely out of conceptual desperation rather than any genuine respect for a more left-leaning view, and the people elected them.

Sure, it wasn’t enough to prevent the Republicans landing the Presidency in 2032. But even the right-wing demagogues, whose veins popped out of their furious necks in much the same way that the Aztecs were drawn to ritual sacrifice, couldn’t gainsay that actually paying people a living wage and accounting for their heightened productivity had curbed both inflation and crime. The public copulation trend had fizzled out, replaced by a new self-love meme in which people became more encouraged to build off of the conceptual masturbation video framework initiated by Beautiful Agony and upload videos of themselves happily engaged in self-pleasure, which had the additional benefit of quelling the dangerous alt-right incel movement that had flourished for a good fifteen years. Somehow, the left and the right could find something to agree on. Everyone liked sex. Self-pleasure was also something that those who believed in abstinence before marriage could be included in. And while the more fundamentalist strains of Christianity thought this was all a moral catastrophe, several progressive-minded pastors had pointed out that this was better than people openly fucking in parks, cafes, and restaurants. And while dating apps had toppled on the verge of bankruptcy for the last few years (to say nothing of dating, which had become more cost-prohibitive during the 2026 recession), when the tech companies began encouraging people to include videos of themselves masturbating from the neck up, the strange honesty of being able to see how someone looked during an orgasm resulted not only in heightened sex, but healthier relationships. There were more enduring marriages (many of them rooted in the rising trend of ethical non-monogamy) and fewer divorces.

Celebrity scandals became less scandalous. When your spouse had an affair, there was more honest talk. And because people were a lot happier, more peaceful, and more comfortable with expressing their sexuality, the religious right swiftly descended in popularity. I mean, who wanted to get out of bed on a Sunday morning, put on a constricting necktie or a dress with a constraining undercarriage and listen to some pompous pastor expatiate about the professed virtues of the Holy Bible? Some churches were so desperate to stay afloat that they constructed glory hole rooms next to the confession booths. And when releasing your tensions — often to a frustrated housewife or a man who had stayed closeted for most of his life, both thrilled by the sudden acceptance — proved more popular than revealing your sins, even staid and humorless organizations like the Catholic League had to confess that they had lost the culture wars. They formed postmortem committees and tried to figure out new ways to court their declining constituencies. But it was all for naught.

And because people knew that there were all these new private and nonjudgmental venues to explore their kinks, there was a return to the enticing mysteries of meeting people without judging them solely on their social media footprint. The revenge porn problem was nipped in the bud. How could you humiliate an ex by despicably posting an old sex video if she had already beaten you to the punch?

After EveryoneFucks.com had gone bankrupt — in large part due to the erratic insanity of a billionaire CEO who burned through VC money faster than Elon Musk had — a new open source movement had arrived — one similar to the Fediverse — where a code of conduct was practiced and people were no longer publicly shamed for the spicy videos they posted. And this proved so paradigm-shifting that not even an obnoxious British writer named Ron Johnswain could find a conceptual hook for his facile Gladwellian books anymore — in large part because Johnswain had constructed his flimsy self-help premises without considering anyone other than damsels in distress. Johnswain was revealed as the knee-jerk huckster he had been all along and not even his annoying high-pitched British accent could win him an audience. He returned to Britain in shame to manage a Tesco supermarket.

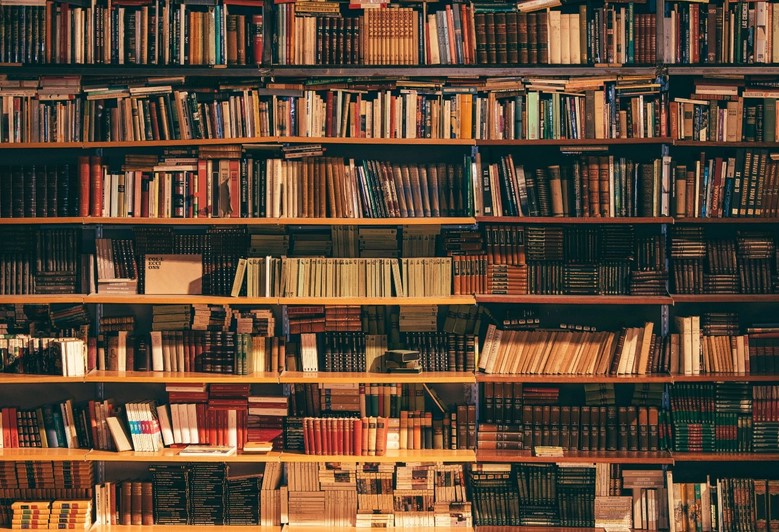

Because the literary Daves had proven to be so monstrous during the Stroller trial (deemed the “trial of the century”), which had exposed the sex trafficking ring in all of its cruel depravity and caused Sophie Van Kleason, Clark Mannix, Bill Flogaast and numerous others to land long prison sentences, it took a good nine years before the publishers would buy a manuscript from anyone named David ever again. A few distinguished MFA workshops had even declined entry to anyone named David. Because Davids could no longer be trusted. Which wasn’t entirely fair to the more innocuous Davids out there. And when the David Oppression Movement emerged at Zuccotti Park in 2038, with numerous Davids descending on New York and declaring that they had the right to write novels, there was not only a new David Renaissance, but an unexpected rise in literacy. Numerous articles had declared the novel dead, but it was still quite alive — in large part because anyone with even a vague command of spelling and grammar simply didn’t know how to shut the fuck up.

And Ezmerelda Gibbons had emerged as the hero, even making the cover of the New York Times Magazine in a splashy profile. When Benjamen Stroller had been revealed as the man she had performed oral sex on in her final OnlyFans video, and the disturbing coercive measures he had used to silence her had at long last been released to the public, she wrote a memoir, which sold three times as much as Ali Breslin’s volume had. The film rights had been optioned for $4 million, though not without Ezmerelda exacting a contractual condition for Sven to serve as director of photography. Ezmerelda stopped production on Toking for Elders, but the backlist episodes proved insanely profitable. Because everyone wanted to know every detail about Ezmerelda’s story.

And on a spring day in 2031, Ezmerelda and Sven were sitting in Velseka at 2 AM after attending the film premiere of Not the New Messiah at the Paris Theatre and attending a ridiculous after party in which many Hollywood people had offered the two of them dubious promises of creative freedom and financial lucre. New York City was the last place on earth that even the quasi-famous could sit down and enjoy a meal without being mobbed. Sven spooned his borscht and Ezmerelda laughed when not eating her stuffed cabbage.

“How did you come up with that final shot?”

Sven picked up his phone and texted her. He still refused to talk.

The director had no idea what to do. John Ford seemed a good fit.

“John Ford?”

Sven delicately set down his spoon and held up his finger, urging her to watch. He picked up one of the paper menus and formed it into an improvised cowboy hat. And then he walked slowly towards the door. He looked back to see if Ezmerelda had figured it out.

“Oh! The Searchers!”

Sven returned to the table and excitedly nodded his head.

“But I’m not a racist.”

It was a joke.

“A joke?”

None of the film critics have figured it out yet.

“Oh!”

And once they do, they’re going to be pissed off.

It was certainly true. They’d been crazy about Not the New Messiah and there was early Oscar buzz.

“They mythologized me. They turned me into some paragon of virtue. Me! Of all people!”

Sven nodded.

“Sven, are you ever going to talk with me? We’ve known each other long enough to move past the Harpo act. Besides, the New York Times called me the ‘new Oprah.'”

“Okay,” said Sven.

Ezmerelda spit out her holubtsi. His voice was beautiful: dulcet, bright, and — she couldn’t deny — sexy as hell.

“Sven! Your voice is gorgeous.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“What?”

“If I talk, they’ll find a reason to hate me.”

“But you’re hot, man! Teflon proof! For fuck’s sake, Paul Thomas Anderson wants you to shoot his next movie!”

“They canceled me when I spoke up.”

“But, dude, we’re winning! Look around us. People are actually enjoying themselves.”

And it was true. A couple swiftly falling in love with each other held hands. A group of twentysomethings laughed over their disastrous failure at the Rumpus Room. And a man who had looked very sad and lonely and friendless when they had walked in was now starting to smile after two guys had the decency to introduce themselves. And the three of them were now picking away at their beef stroganoff and making funny airplane sounds.

“Come on Sven. It hasn’t been this peaceful since Obama was President.”

“It will pass.”

“What?”

“Everything passes,” said Sven. “Ups and downs. It’s part of the human cycle.”

“You want to know something, Sven?”

“What?”

She placed her thumb and her forefinger to her lips and zipped it. Then she picked up her phone and started texting Sven.

Do you think I can last a week like this?

Sven laughed.

“They’re going to hound you.”

Who?

“The media.”

Let them. I’m done being their Messiah.

“They’ll offer you lots of money.”

I have everything I need.

“They’ll want your thoughts on everything.”

They should learn to think for themselves.

A young woman approached the table.

“Excuse me,” she said. “Are you…?”

“I think you have the wrong person,” said Sven.

“But she’s…she’s Ezmerelda Gibbons! Oh my god! I loved your memoir. It changed my life!”

Ezmerelda pointed to her mouth and held her hands up in the air.

“Oh! You’re mute! I’m so sorry.”

“Don’t worry about it,” said Sven. “She gets that a lot. Have a good night.”

The young woman curtsied and returned to her friends.

“You see,” said Sven. “Staying silent is a choice. And it’s very empowering.”

I get it now.

“I knew you would.”

But why are you talking now?

“Because now it’s time.”

Sven paid the bill and the two walked out of Veselka. They hugged and said goodbye. The Lyft driver was one of those mercifully silent types. And in the back of the car, Ezmerelda deleted her YouTube channel, her TikTok account, her Instagram account, and pulled the plug on her website. Let them find somebody else to speak for them. Let her audience speculate about why she had done this or what she was now doing. They would forget about her, just as they forgot about anyone who had landed fifteen minutes of fame.

She stayed up to watch the sun rise. She was too excited to sleep. There was a lambent blaze upon the glistening streets. And Brooklyn looked more beautiful, more gravid with exciting possibilities. She looked out the window and watched the people walking to the subway, the kids laughing on their way to school, the old school dude beatboxing on the corner, and a woman dancing as she cleaned her car. And she laughed. Everything was going to be all right. She finally knew what real life was. All she had needed to do was to cede the stage.

Brooklyn, New York

November 1-30, 2022

(Word count: 52,702/50,000)

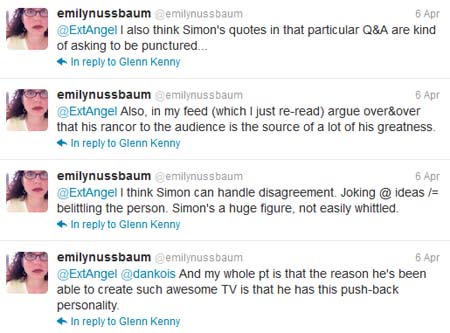

Correspondent: Well, the problem we have here too — and this is really frustrating. David Simon, for example, recently

Correspondent: Well, the problem we have here too — and this is really frustrating. David Simon, for example, recently