(This is the thirtieth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: A House for Mr. Biswas.)

Richard Hughes’s A High Wind in Jamaica is the wild and bracing corrective to William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (forthcoming at ML #41) that I never knew I needed. Truth be told, the two books I am least looking forward to revisiting during the course of this ridiculously ambitious and time-consuming project are J.D. Salinger’s A Catcher in the Rye (forthcoming at ML #64) and Lord. Both novels meshed with me when I was an impressionable high school kid who didn’t know any better, but I have assiduously avoided rereading both volumes as an adult — much in the way that you hang down your wiser and more mature head over some of the dodgier cartoons you advocated as a child. (For the record, in my adulthood, I still abide by The Rocky & Bullwinkle Show, the decades-long catalog of Warner Brothers cartoons, and — if you get me on the right day — Robotech and Star Blazers.)

Thankfully, I had no such qualms with High Wind; in large part because, unlike Golding, Hughes isn’t so obsessed with plugging in values — the novel as a Sudoku puzzle? — to uphold his Great AllegoryTM (and thus literary posterity). The older you get as a reader, the more you welcome the fresh shock of the visceral: those exotic and sometimes unsettling voices you may not encounter in the real world.

Thankfully, I had no such qualms with High Wind; in large part because, unlike Golding, Hughes isn’t so obsessed with plugging in values — the novel as a Sudoku puzzle? — to uphold his Great AllegoryTM (and thus literary posterity). The older you get as a reader, the more you welcome the fresh shock of the visceral: those exotic and sometimes unsettling voices you may not encounter in the real world.

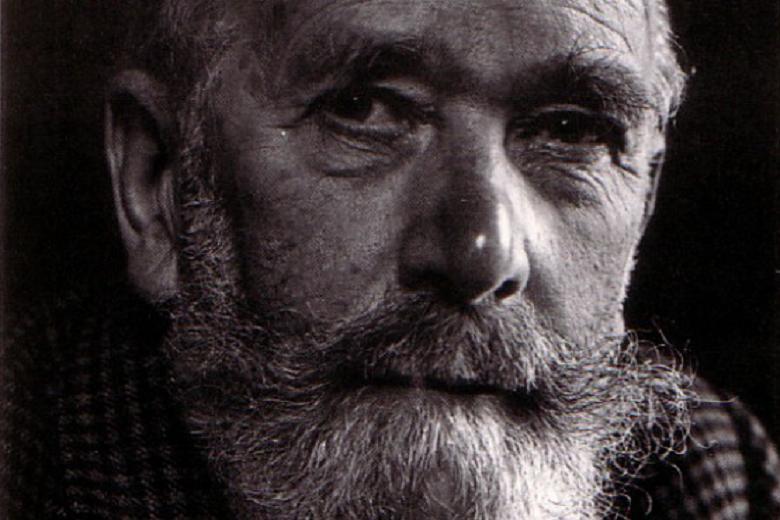

Hughes was twenty-five years ahead of Golding when it came to writing a novel about children losing their civilized patina as they travel deeper into the wild and aberrant vales of anarchism (in this case, by dint of a ragtag gang of pirates). But his exquisite command of atmosphere shows that he was arguably more subtler than Golding, permitting the transformation of his children to become something of a shock in part due to the great care he took with his prose. High Wind was one of only four novels that Hughes wrote. (And aside from High Wind, I especially recommend In Hazard.) He was more of a playwright, a poet, and a journalist than a fiction writer — in large part because the lapidary approach he took with his sentences significantly slowed him down. But despite his bradykinetic progress, High Wind proved to be such a literary sensation that it turned Hughes into a notable figure saddled with controversy, literary renown, and even a modestly burgeoning financial cushion.

The novel’s setup involves the Bas-Thornton children, who flirt with feral wonders in the Jamaican wild when not relishing their privileged comforts at a plantation named Ferndale. A storm devastates their idyllic paradise. And as they sail back home to England, the children are scooped up by pirates.

When the pirates do board the ill-fated Clorinda (complete with Captain Narpole sleeping through the whole imbroglio, saving face later with a devastatingly bleak letter of lies), Hughes is crisply fastidious about describing these interlopers against type:

With this second boatload came both the captain and the mate. The former was a clumsy great fellow, with a sad, silly face. He was bulky; yet so ill-proportioned one got no impression of power. He was modestly dressed in a drab shore-going suit: he was newly shaven, and his sparse was pomaded so that it lay in a few dark ribbons across his baldish head-top. But all this shore-decency of appearance only accentuated his big splodgy brown hands, stained and scarred and corned with his calling. Moreover, instead of boots he wore a pair of gigantic heel-less slippers in the Moorish manner, which he must have sliced with a knife out of some pair of dead sea-boots. Even his great spreading feet could hardly keep them on, so that he was obliged to walk at the slowest of shuffles, flop-flop along the deck. He stooped, as if always afraid of banging his head on something, and carried the backs of his hands forward, like an orangutan.

Much as Knut Hamsun seemed to anticipate the hardboiled existential feel of Jim Thompson and James M. Cain in 1890 (thank you also, late and great translator Sverre Lyngstad!), so too does Hughes depict the professional working-class criminal just before the gaudily garbed grunt became a staple of noir. These pirates do make a perfunctory effort to look presentable (the captain — later revealed to be a Danish German-speaking ruffian named Jonsen — has gone to the trouble of shaving and pomading what is left of his hair), but they are also makeshift in their sartorial choices. Hughes’s beautiful choice of “dead sea-boots” suggests something vitiated and unholy at work here. (Indeed, one of the buyers who unloads the booty is a vicar, described as “less well shaved than he would have been in England.” Later, a warped nativity play is performed to entertain the pirates. Even later, the song “Onward, Christian Soldiers” is evoked in creepy fashion.) And Jonsen’s desperate attempt to keep his fancy bespoke slippers on — coupled with the telltale pocks of his aloof hands, which resemble a spastic animal — is just one of many examples of the dry exacting comedy that Hughes doles out gently throughout this deranged adventure tale. There’s also a mysterious first-person narrator serving almost as a cosmic god offering mordant asides. Indeed, the standoff between Marpole and these thugs reminded me of the “civilized” exchange between Barry and the highwayman in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. (In Barry Lyndon, Kubrick also had a sardonic narrator in the form of Michael Hordern’s arch commentary, which also dished up bone-dry asides on how we are all barely disguised animals beneath the human sheen. Was Kubrick familiar with Hughes? We may never know, although it is worth noting that a young Martin Amis did appear as one of the kids in the 1965 film adaptation of Hughes’s novel.)

Yet the look of these pirates is enough to ignite a modest crush within Margaret, one of the children, who marvels at their beauty. In an age in which television shows like Euphoria and high school cinematic classics like Fast Times at Ridgemont High or Ferris Bueller’s Day Off are heralded for using transgressive behavior to depict teens as “adults” (one can likewise see this approach nimbly executed in Megan Abbott’s more recent novels, which have used this storytelling device by framing kids through the subcultures of ballet, cheerleading, and hockey), it’s impossible to overstate the big risk that Hughes took here in 1929. During the hurricane that plagues Jamaica, Hughes also foreshadows how living in a state of nature can inevitably subsume anyone — even a child — by having a domesticated pet named Tabby ruthlessly chased by wildcats.

You will, alas, have to contend with the novel’s appalling and off-putting racism (“there is, after all, a vast difference between a negro and a favorite cat,” writes Hughes when both die after a hurricane and there is a cruel treatment of a monkey on the high seas, which suggests an unsettling metaphor). But the sheer weirdness that forms the backbone of this sweeping story swiftly atones for these hoary and horrendous “cultural values.”

High Wind is also the first recorded instance of the Hangman’s Blood, a cocktail later favored by Anthony Burgess. Seventeen years ago, I persuaded a bartender in the Upper Haight to make me this famous libation. It was, I am sad to report, quite ghastly. I never tried it again. Hughes himself also understood what a hideous mix it was, describing it as possessing “the property of increasing rather than allaying thirst, and so, once it has made a breach, soon demolishes the whole fort.”

Subconsciously, too, every one recognizes they are animals — why else do people always laugh when a baby does some action resembling the human, as they would at a praying mantis?

The children adapt to their new life much like many of today’s bored kids stare into the vacuity of their digital screens for constant stimulation. When one of their number dies, Hughes eerily notes how quickly accustomed they become to an empty bed. When Jonsen withholds the “three Sovereign Rules of Life” on the basis of their youth, Edward replies, “Why not? When shall I be old enough?” Indeed, reading High Wind in 2022 is rather eldritch, particularly in the shock of recognizing such everyday behavior among children today. Hughes does not shy away from how boredom can turn kids unruly and mischievous quite fast. Margaret speaks “with an eagerness that even exceeded the necessities of politeness in its falsity.” When the first mate attempts to inveigle the kids by mentioning a famous pirate named Rector of Roseau, the children quickly see through the superficiality of the apocryphal origin story, puncturing the first mate’s plot holes faster than the Comic Book Guy on The Simpsons. And the children strike back, with Hughes even describing a corporeal awakening among Emily.

I certainly don’t want to spoil how the kids transform. But it is subtly disconcerting, with a clever nod to the Flying Dutchman. We are left to wonder whether this particular group of kids was fated to turn out this way, even if the pirates had never kidnapped them, or if feral circumstances shaped their transmutation. Hughes, to his credit, lets the reader off the hook somewhat with this aside, pointing to how children are regularly underestimated:

Grown-ups embark on a life of deception with considerable misgiving, and generally fail. But not so children. A child can hide the most appalling secret without the least effort, and is practically secure against detection. Parents, finding that they see through their child in so many places the child does not know of, seldom realize that, if there is some point the child really gives his mind to hiding, their chances nil.

Given how problem children have been a pain in the ass for so many parents over the years, it’s rather surprising that it took so long for literature to point this out. Hughes’s immaculately written masterpiece — complete with its alligators and earthquakes as odd forms of fierce incitement and its wry asides about our assumptions about children — was one of the first major works of fiction to interrogate this discomfiting truth. And, even today, A High Wind in Jamaica is a bold and welcome reminder that kids are not to be underestimated. In an epoch in which moronic milquetoasts ban Maus from classrooms for the most arbitrarily intransigent concerns (just read the meeting minutes), High Wind — complete with its chilling final sentence — is a swift kick in the ass to the cowardly and unadventurous sensibilities that prevent us from being honest about what anyone is capable of becoming and how so many of these disturbing possibilities hide in plain sight.