In 2007, the French Ministry of Culture had an annual budget of €3.18 billion. (To give you some sense of how this fits into the grand scheme of things, France’s national budget in 2005 was €288.8 billion. So that’s roughly around 1% of the national budget.) While the National Endowment of the Arts budget is at its highest mark since 1995, the NEA budget as a whole amounts to $144.7 million. A mere €91.94 million to France’s €3.18 billion.

In 2007, the French Ministry of Culture had an annual budget of €3.18 billion. (To give you some sense of how this fits into the grand scheme of things, France’s national budget in 2005 was €288.8 billion. So that’s roughly around 1% of the national budget.) While the National Endowment of the Arts budget is at its highest mark since 1995, the NEA budget as a whole amounts to $144.7 million. A mere €91.94 million to France’s €3.18 billion.

A few more things to consider: Irish writers live tax free. In Cuba, art school is free and artists often earn a better living than many other professions. The German public arts funding model permits the nation to have 23 times more full-time symphonies per capita and 28 times more full-time opera houses than America. Last year, Italy raised its annual arts funding to $573 million — an annual budget more than three times that of the NEA. Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, unlike the NEA’s site, explains why it’s important to build a society that values culture on its front page and had an annual budget of 100.6 billion yen for 2006. (For those playing at home, that’s a little under a billion in American dollars.)

As an American, this embarrasses me. It’s bad enough that we’re the only industrialized nation without socialized medicine. It’s terrible that this nation, when stacked against others, is especially shameful on parental leave. But one would think that the “richest country in the world” would be somewhat capable of doling out a few dollars more to artists. Because, as anybody who works full-time in the arts knows, this is hardly a lucrative occupation.

Of course, there are grants. But the ones that the NEA does mete out must fall under “general standards of decency” — a coded phrase for “play it safe if you want to work full-time as a subsidized artist.” That’s hardly the democratic thinking one expects from a federal republic that frequently misinforms its citizens about its purported democratic values.

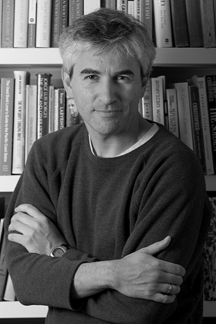

On Wednesday night, shortly after attending the big Mailer tribute at Carnegie Hall (a lengthy report of this will follow), I entered the appropriately named Commerce Building for a reception devoted to the NEA’s latest title in its Big Read campaign. There were few people there under the age of forty. David Kipen stood before the crowd, preaching to the converted about the current crisis in literature.

I listened to Kipen talk. He described his apparent frustration with the San Francisco Chronicle failing to hire another full-time book critic to replace him, conveying the reality of newspaper book sections facing serious cuts, and suggesting that the Big Read campaign was intended as a partial answer to the Reading at Risk hysteria.

I listened to Kipen talk. He described his apparent frustration with the San Francisco Chronicle failing to hire another full-time book critic to replace him, conveying the reality of newspaper book sections facing serious cuts, and suggesting that the Big Read campaign was intended as a partial answer to the Reading at Risk hysteria.

When the talk was over, I approached Kipen. He was stunned to see me — in part because he still thought that I was in San Francisco. He thought that I was Kevin Smokler, a man who had collected many essays in his book, Bookmark Now, ably pinpointing the folderol behind the Reading at Risk hysteria and observing that reading was quite alive in many corners.

“I’ve got an idea that will kill two birds with one stone,” I said. “Something that addresses what you were talking about.”

“People were actually paying attention?” said Kipen, apparently astonished that anyone would take what he had to say seriously. This seemed a surprising attitude from a “Director of Literature.”

I asked Kipen if he really believed that reading was dead. He confessed that the Reading at Risk report was more of a “diagnostic.”

I then begin to outline to him a very simple idea. If newspapers were dying and reading was “at risk,” why not have the NEA sponsor an online book site that would function very much like the WPA Federal Writers Project? A place where emerging critics hustling from newspaper to newspaper could find a place to hone their thoughts about literature. A place that could subsidize current print critics, litbloggers, literary podcasters, and other parties. Something that would involve hard editing and encouragement. Essays that were just as committed to novels in translation, small presses, genre, and the like as they were the latest volume from John Updike. Not only would such a site be a training ground for emerging critics, but it would also be a place for freelancers to go when the newspaper markets dried up. Why not put the money in the hands of the impassioned and the thoughtful? After all, if they have the ability to get people thinking about reading, doesn’t this make more sense than spending money on a program in which the NEA deems one book — in this case, The Maltese Falcon — that everybody needs to read?

(To give you a sense of how little this idea would cost, $104,000 could pay for five reviews a week, 52 weeks a year, with each writer paid $400 per piece. Given this math, I’m wondered how much it had cost Kipen to rent out the Commerce Building and to pay for hotels, flights, food and drink. $10,000 maybe? Kill ten social functions along these lines and give the money to writers.)

(To give you a sense of how little this idea would cost, $104,000 could pay for five reviews a week, 52 weeks a year, with each writer paid $400 per piece. Given this math, I’m wondered how much it had cost Kipen to rent out the Commerce Building and to pay for hotels, flights, food and drink. $10,000 maybe? Kill ten social functions along these lines and give the money to writers.)

Kipen attempted to brush this idea off, presumably because this sounded somewhat Communist. But I wouldn’t let him get away. In Kipen’s defense, I should also point out that I was quite effusive about all this. And this vivacity on my part tends to frighten some people. But since Kipen was likewise an animated person, I figured he could take it. Little did I realize that, over four years, Kipen had transformed, espousing the kind of muleheaded resistance to fresh and lively literary coverage that Frank Wilson once alluded to about management. Kipen had become a company man.

He had no real clue about what was happening on the Internet. (He still believed that John Freeman was President of the NBCC. But he intimated that there had been a few talks. I’m wondering, however, if Freeman’s efforts had encountered similar resistance.) I told Kipen a few things that I had accomplished with The Bat Segundo Show. Nearly 200 conversations, with more in the can. Emails from people who told me that I had transformed their commutes from plodding sessions with FM radio DJs playing lousy music into intelligent and entertaining talk that made them alive. I told him that a number of people had also emailed me about the Jeffrey Ford interview, pointing out that they hadn’t heard of Ford before and that, because of the interview, they were planning on checking out his work. I also told him about an interview I had scheduled with another author who was coming through New York. I had learned that this author didn’t have any additional interviews lined up except for me. The publisher had likewise dumped this incredible novel into the market as a paperback original. This was a considerable injustice that something like a NEA-sponsored program could correct.

“You’ve got something against paperback originals?” said Kipen, desperately trying to change the subject, his interest more in canapes than concepts.

I told him that I didn’t. I told him that he knew very well what the reality was. And that he was in the position of doing something about this in the NEA. Grants had helped the likes of Sherman Alexie. Why not help others? There needed to be more podcasts, more writing, more places for the literary. More places that could help starving writers so that they wouldn’t have to turn to day labor or temp work. The whole thing could be kickstarted on comparatively little cash. It could be initiated by the NEA.

Kipen was more fascinated by a drifting salver.

He showed somewhat more interest in a woman, who was not forthright about identifying herself to me. This woman declared that she was on a board of directors for an “online book review” project with Eric Banks and Nan Talese. This, of course, has been in the works since November and is highly suspect — given that Talese insisted that “the best book reviews are the ones in People magazine and Entertainment Weekly.” I don’t want to be a snob about magazines for the vox populi, but how exactly does this emphasis take into account the quality reviews frequently found in Bookforum or the New York Review of Books? There was also one major ethical conundrum: this venture would be subsidized by publishers. But what review space would there be for publishers who weren’t sponsoring the site? And would such a cozy relationship encourage more favorable reviews?

I told this woman that, contrary to her “innovation,” there was, in fact, an online book review already. It was known as the litblogosphere. There was Dan Green and the Quarterly Conversation. I told her that there were essays on my site five days a week (or thereabouts) and that everything was edited. Apparently, I grabbed her attention. I was out of cards. So I wrote my email address on the back of Kipen’s business card.

The fact that this woman showed more attention about the future of literature than the NEA’s Director of Literature suggests that the NEA is in serious trouble. It can’t be an accident that private interests are more intrigued than those governmental agencies purportedly set up to provide for the public. Kipen can bitch all he wants about the decline of the book review. But if he truly believes that “the indicator species for American daily journalism is the book review,” I certainly don’t see the NEA offering any kind of alternative, much less listening to people who have ideas.

So unless David Kipen can demonstrate that he’s less interested in dictating to the public what they need to read and more interested in helping those who are effectively getting people excited about books, I must believe him to be an unsuitable representative for promoting literature in this country. Then again, given the penurious support this nation gives to the arts, I’d say that Kipen is as American as apple pie.

[4/14/08 UPDATE: Clarifying the extent of this venture, Eric Banks has emailed me: “I’m not sure who the woman was who approached you at the Good Reads event, but there is no ‘board of directors’ for the review that Nan and I have at various times discussed. The way you outlined the funding for such a review is not correct — and what I have to stress as well is that this is at this point no more than a theoretical idea (guess that’s slightly redundant, but you know what I mean) that Nan and I have talked about. At one point we did speak to the AAP about some sort of advertising commitment on its part (and that was for collective support), but that would have been under the auspices of Bookforum–it would have been proposed as an expansion of bookforum.com and was intended precisely to allow Bookforum to cover more books than it is able to do given the size and frequency of the review.” I will, as time permits, conduct some additional investigations about this “theoretical idea.”]

The music, however, seemed to be dying. The actual old-timers, the ones who had taught the hippies how to do it in the 1970s, were actually dying, one after the other. On my first visit to a festival down south in 1997, I seemed to be one of about five musicians under the age of thirty. Old-time music had seen a big comeback with the folk revival—people my parents’ age—but from where I stood, it seemed like that might be the end of it, for reasons I couldn’t fathom.

The music, however, seemed to be dying. The actual old-timers, the ones who had taught the hippies how to do it in the 1970s, were actually dying, one after the other. On my first visit to a festival down south in 1997, I seemed to be one of about five musicians under the age of thirty. Old-time music had seen a big comeback with the folk revival—people my parents’ age—but from where I stood, it seemed like that might be the end of it, for reasons I couldn’t fathom.

This film may be something of a gamble for Wong Kar-Wai, but the die is miscast. You simply don’t hire a hunky leading man like Jude Law to be a cafe proprietor. Not if you care about verisimilitude. Law is as flagrant as John Wayne’s Roman centurion supervising Christ’s execution in The Greatest Story Ever Told. The good people who work in the service sector remain largely anonymous, and it would have behooved Wong Kar-Wai to settle for a more interesting character actor in this part. And you don’t hire a doe-eyed cipher like Norah Jones to play a character who has no goal in life other than to work all the time and wander aimlessly around the States. Let me put it to you this way: The paint currently peeling outside my window has more personality than Norah Jones’s execrable Elizabeth, who learns nothing from being mugged on a subway or being dumped by her main man.

This film may be something of a gamble for Wong Kar-Wai, but the die is miscast. You simply don’t hire a hunky leading man like Jude Law to be a cafe proprietor. Not if you care about verisimilitude. Law is as flagrant as John Wayne’s Roman centurion supervising Christ’s execution in The Greatest Story Ever Told. The good people who work in the service sector remain largely anonymous, and it would have behooved Wong Kar-Wai to settle for a more interesting character actor in this part. And you don’t hire a doe-eyed cipher like Norah Jones to play a character who has no goal in life other than to work all the time and wander aimlessly around the States. Let me put it to you this way: The paint currently peeling outside my window has more personality than Norah Jones’s execrable Elizabeth, who learns nothing from being mugged on a subway or being dumped by her main man.  I should also observe that Darius Khondji’s cinematography is taken with doors. There are conversations in doors. A PULL sign on the door of a Memphis bar gets prominent coverage. If My Blueberry Nights doesn’t work as Food Network counterprogramming, then it will certainly excite any JELD-WEN employee who remains convinced that his hard work is a thankless job.

I should also observe that Darius Khondji’s cinematography is taken with doors. There are conversations in doors. A PULL sign on the door of a Memphis bar gets prominent coverage. If My Blueberry Nights doesn’t work as Food Network counterprogramming, then it will certainly excite any JELD-WEN employee who remains convinced that his hard work is a thankless job.