“Macdonald had given the hint that the clue to discovery was not in the substance of one’s idea, but in what was learned from the style of one’s attack.” – Norman Mailer, The Armies of the Night

Forty-four years ago, on a temperate October afternoon charged by a mass temper, more than 100,000 people occupied the Lincoln Memorial to protest the Vietnam War. Among them were Norman Mailer, Robert Lowell, and Dwight Macdonald. A good third of this group, led in part by the literary trio, would soon march upon the Pentagon with the intention of levitating it. Mailer would write one of his best-known volumes from these events, earning both a National Book Award and a Pulitzer Prize. But Mailer could not have done so without Macdonald, whose fiery approach had helped him “to get his guns loose.”

For the critic Macdonald, such heady protests were old hat. During World War II, he had raised hell through the antiwar Workers Party against the collective failure to condemn Soviet foreign policy. He was also involved in the March on Washington Movement, an effort to end racial discrimination in the armed forces. As the cultural critic James Wolcott has suggested, Macdonald “wrote and spoke as if fear and conformity were foreign to his nature and affronts to the spirit of liberty.” Yet he was inclusive of any emerging figure who posssessed these virtues. Of an antagonistic young man who challenged the arrogant Harvard dean McGeorge Bundy in the Atlantic‘s pages, Macdonald was to confess that he “could not help liking [William] Buckley.”

After a shaky political start as a waspy young journalist on the make, Macdonald revolted against his employer Henry Luce and began editing Partisan Review, where he raised his pugilistic fists through words. When not attacking Stalinism from the left (later in life, he would identify himself as a “conservative anarchist”) or questioning the responsibility of intellectuals, Macdonald spent time successfully persuading the likes of Edmund Wilson and George Orwell to contribute to his pages. But Macdonald’s contentious personality eventually led him to form his independent journal, Politics, which flourished from 1944 through 1949, until Macdonald’s energies and resources diminished.

Never especially good at mushrooming his ideas and views into books, Macdonald became a pen for hire, directing his attentions to perceived cultural threats: homogenization, dry academic writing, and sundry commercial forces. Many of Macdonald’s best cultural essays have been collected in a recently published volume, Masscult and Midcult: Essays Against the American Grain. These pieces permit us to see the varying fluency with which Macdonald applied the political attack dog approach so valued by Mailer.

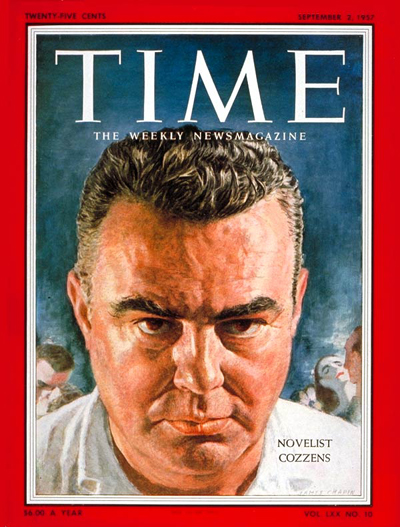

Macdonald functioned best when he had a fixed target in his crosshairs. “By Cozzens Possessed,” a career-killing takedown of the novelist James Gould Cozzens, is a merciless exercise, attacking the then revered 1957 novel, By Love Possessed, for its prose style, its use of arcane words, the feverish and often thoughtless critical acclaim, and its inaccurate portrayal of human behavior. It is so brutal and stinging an assessment that it might almost serve as a handbook for any young critic hoping to make a big splash. But Macdonald stood for a clear set of values. He wished to protest “the general lowering of standards” and “the sober, conscious plodders…whose true worth is temporarily obscured by their modish avant-garde competitors.”

Macdonald functioned best when he had a fixed target in his crosshairs. “By Cozzens Possessed,” a career-killing takedown of the novelist James Gould Cozzens, is a merciless exercise, attacking the then revered 1957 novel, By Love Possessed, for its prose style, its use of arcane words, the feverish and often thoughtless critical acclaim, and its inaccurate portrayal of human behavior. It is so brutal and stinging an assessment that it might almost serve as a handbook for any young critic hoping to make a big splash. But Macdonald stood for a clear set of values. He wished to protest “the general lowering of standards” and “the sober, conscious plodders…whose true worth is temporarily obscured by their modish avant-garde competitors.”

Such sectarian language sounds not unlike Macdonald’s political missives from decades before. Sure enough, it was this nexus of self-deception and ascension in status which served as the common whetstone for Macdonald to sharpen his sword. Before Macdonald begins his attack, he establishes Cozzens’s financial and critical success in the first paragraph, showing that Cozzens in a position to take it. (This is very much in the tradition of American hatchet jobs. Mark Twain’s essay, “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses,” also opens with three epigraphs attesting to the alleged worth of Cooper’s writing.)

Macdonald’s essays also inadvertently raise the question of whether a critic really deserves this much power. In his invaluable John Cheever biography, Blake Bailey made a convincing case that Macdonald’s drive-by impacted the 1958 National Book Award, pushing Cheever’s The Wapshot Chronicle into the winning slot. (Cheever thought highly of By Love Possessed, calling it “excellent” in his journals. Years later, after learning that Cozzens had revered his work, the guilt-ridden Cheever became so upset that he came close to sending Cozzens a family heirloom.) Did James Gould Cozzens sully culture as much as the Great Books (which Macdonald rightfully chided as “densely printed, poorly edited reading matter”) or the Revised Standard Version of the Bible (which Macdoanld rebuked for destroying the King James’s lexical zest)? Probably not, especially if one values the positive qualities of oddity.

Macdonald sent copies of his essays to his targets, thereby permitting them to respond, if so desired. Thus, in book form, Macdonald’s essays frequently contain appendices, such as George Plimpton lodging his objections and corrections at the end of Macdonald’s attack on Hemingway. Reading such annotations in the early 21st century, which closely resemble today’s blog and comment culture, one gets the uncanny sense that, were Dwight Macdonald around today, he would likely be some wild-eyed blogger operating out of a ramshackle Brooklyn apartment.

In an age when many online enthusiasts think nothing of embedding Amazon links into their blogs or sign away their Goodreads reviews without consideration of the “royalty-free, sublicensable, transferable, perpetual, irrevocable, non-exclusive, worldwide license to use, reproduce, modify, publish, list information regarding, edit, translate, distribute, publicly perform, publicly display, and make derivative works of all such User Content and your name, voice, and/or likeness as contained in your User Content,” there are ineluctable connections between culture and commerce. And Macdonald’s lengthy essay condemning Masscult (“a parody of High Culture”) protests a cultural world in which “everything becomes a commodity, to be mined for $$$$, used for something it is not, from Davy Crockett to Picasso. Once a writer becomes a Name, that is, once he writes a book that for good or bad reasons catches on, the Masscult (or Midcult) mechanism begins to ‘build him up,’ to package him into something that can be sold in identical units in quantity. He can coast along the rest of his life on momentum; publishers will pay him big advances just to get his Name on their list; his charisma becomes such that people will pay him $250 and up to address them (really just to see him); editors will reward him handsomely for articles on subjects he knows nothing about.”

Macdonald’s argument may need to be revised to account for recent technological developments, but his general beef with cultural philistines still holds considerable water. This year, we have seen bestselling novelist Lev Grossman, whose books are now being developed into a FOX television series, write a review of George R.R. Martin’s Dance with Dragons, describing it as “the great fantasy epic of our era” without disclosing the fact that Grossman secured a glowing blurb from Martin for The Magicians. Another critic, Laura Miller, openly invites her readers to ban books: “As deplorable as real-life book banning may be, there’s some required reading that those of us at Salon would love to see retired from the nation’s syllabuses simply because we were tortured by it as kids.” Given these affronts to integrity and intellectualism, where is today’s Dwight Macdonald to contend with these two hydrophobic mutts in the woodshed?

Macdonald’s argument may need to be revised to account for recent technological developments, but his general beef with cultural philistines still holds considerable water. This year, we have seen bestselling novelist Lev Grossman, whose books are now being developed into a FOX television series, write a review of George R.R. Martin’s Dance with Dragons, describing it as “the great fantasy epic of our era” without disclosing the fact that Grossman secured a glowing blurb from Martin for The Magicians. Another critic, Laura Miller, openly invites her readers to ban books: “As deplorable as real-life book banning may be, there’s some required reading that those of us at Salon would love to see retired from the nation’s syllabuses simply because we were tortured by it as kids.” Given these affronts to integrity and intellectualism, where is today’s Dwight Macdonald to contend with these two hydrophobic mutts in the woodshed?

It’s certainly easy for a myopic reader to interpret Macdonald’s essays as snark, for Macdonald had a clear enmity for rock music and television. Yet snark, as David Denby has remarked in a book on the subject, involves a contempt for absolutely everyone. While elitist in tone, Macdonald’s cultural essays also commended the proliferation of symphony orchestras and art house movie theaters. He did honor the artistically and intellectually ambitious, although often with brutal paradox. He recognizes Hemingway as a stylistic innovator, yet writes, “I don’t know which is the more surprising, after twenty years, the virtuosity of the style or its lack of emotional resonance today.”

At times, Macdonald’s cultural essays read as if they were more concerned with swimming in a stream of brimstone. His 1972 smackdown of Norman Cousins, editor of a now largely forgotten biweekly magazine, feels more desperate and superficial than Alan Grayson’s recent obliteration of PJ O’Rourke on a recent installment of Real Time with Bill Maher. When he lost his focus, it was easy for Macdonald to reveal hypocrisy. In his 1967 essay “Parajounalism,” Macdonald condemns Tom Wolfe for his cruel assaults on The New Yorker‘s Wallace Shawn, yet lacks the courage to acknowledge his own malicious barbs toward others in the past. And when Macdonald writes about Wolfe’s attack being “more in the kamikaze style – after all he was thirty-three when he wrote it while I was thirty-one when I wrote mine,” one wonders if Macdonald was jealous of Wolfe’s increased attention and his ability to get through to younger readers.

Despite his pugnacity, Macdonald could be kind. In his essay on James Agee not long after Agee’s death, Macdonald writes, “I had always thought of Agee as the most broadly gifted writer of my generation, the one who, if anyone, might someday do major work.” In January 1963, The New Yorker published Macdonald’s essay on Michael Harrington’s The Poverty of America. Macdonald put a considerable amount of work into the piece, which featured an impassioned demand to the upper and middle classes to reverse “mass poverty in a prosperous country.” Macdonald’s essay attracted great attention and helped reverse the book’s flagging sales.

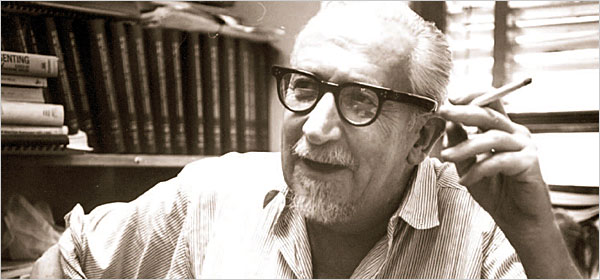

Yet it’s possible that, for all of his righteous exactitude, Macdonald wasn’t kind or motivated enough. His clumsy and alcohol-fueled elitism (according to Michael Wreszin’s page-turner of a biography, A Rebel in Defense of Tradition, Macdonald needed a ration of twelve drinks a day) inspired Saul Bellow to savage him in Humboldt’s Gift. In Bellow’s novel, Macdonald appeared as the “lightweight” intellectual Orlando Higgins, where “his penis which lay before him on the water-smoothed wood, expressed all the fluctuations of his interest.”

Yet it’s possible that, for all of his righteous exactitude, Macdonald wasn’t kind or motivated enough. His clumsy and alcohol-fueled elitism (according to Michael Wreszin’s page-turner of a biography, A Rebel in Defense of Tradition, Macdonald needed a ration of twelve drinks a day) inspired Saul Bellow to savage him in Humboldt’s Gift. In Bellow’s novel, Macdonald appeared as the “lightweight” intellectual Orlando Higgins, where “his penis which lay before him on the water-smoothed wood, expressed all the fluctuations of his interest.”

To offer a Masscult metaphor that Macdonald would loathe: with great power comes great responsibility. If a critic’s responsibility involves standing against the contemptible forces transforming independent voices into soothing consumer-oriented bores who are no different from the hucksters who sell fabric softener, then nearly every working critic in America can learn a lesson from Macdonald. On the other hand, Macdonald’s lack of versatility demonstrates how a prominent tiger can be swiftly forgotten if he doesn’t change his stripes.

Postscript: The above essay was originally scheduled to run in a literary journal. What I did not anticipate was that much of the subtext concerning “style of one’s attack” would be misinterpreted by the estimable editor as a series of attacks. After some lively back-and-forth and many concessions on my part, I was forced to withdraw the piece on amicable terms and publish it on these pages. I still carry great respect for this literary journal and, as far as I’m concerned, the editor is still a sweetheart. But I relate this metafactual episode to demonstrate the distinct possibility that even a quasi-Macdonald approach, one also revealing a distinct arthritic quality in the lunge, may no longer be welcome nor encouraged in our present culture.

I am fairly certain that I found The Old Wives’ Tale compelling for reasons that Arnold Bennett did not intend. After my great excitement with Jack London, Bennett was something of a letdown, reading more like fossilized culch than a lively adventure from the 20th century, although I experienced a great deal of pleasure as characters began to die and as they became needlessly blamed for other deaths. Consider the manner in which Sophia, assigned to watch over her bedridden father, sneaks away for a few minutes to chat with the strapping Gerald Scales. When she returns, something terribly odd occurs:

I am fairly certain that I found The Old Wives’ Tale compelling for reasons that Arnold Bennett did not intend. After my great excitement with Jack London, Bennett was something of a letdown, reading more like fossilized culch than a lively adventure from the 20th century, although I experienced a great deal of pleasure as characters began to die and as they became needlessly blamed for other deaths. Consider the manner in which Sophia, assigned to watch over her bedridden father, sneaks away for a few minutes to chat with the strapping Gerald Scales. When she returns, something terribly odd occurs: