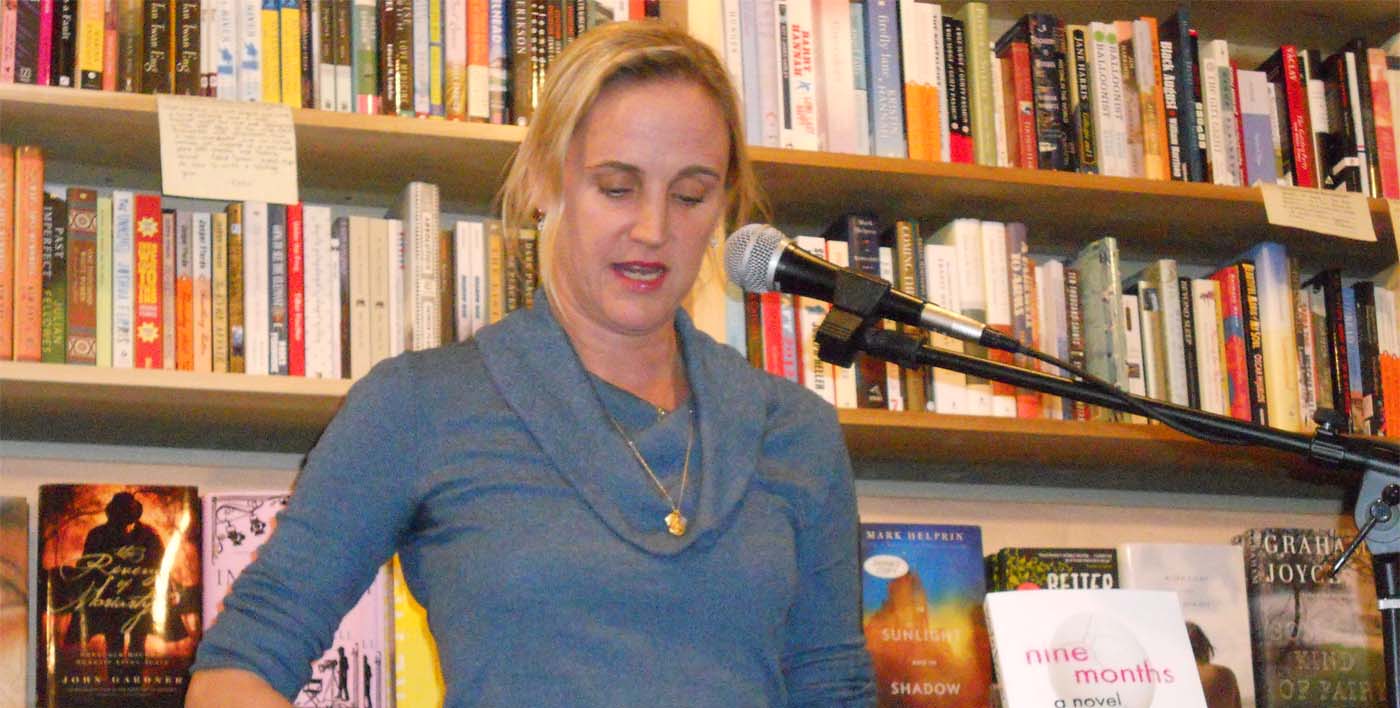

Paula Bomer is most recently the author of Inside Madeleine. She previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #375 and The Bat Segundo Show #481.

Author: Paula Bomer

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: How physically scarred characters inspire dimension inside characters, Flannery O’Connor’s thoughts on the grotesque, how character details create mystery, Dorothea Lange and the Dust Bowl, Jim Thompson and Freud symbols, when “toxic” becomes a cliched adjective to describe people, the tendency for people to seek versions of their family later in life, young people trying to make their own world, when people who make you feel like crap are confused with the right relationship fit, how structure emerges from the liberation of space, contrapuntal tension in “Inside Madeleine,” spending two years working on a novella, the 1980s fashion of people having eating disorders, strange relationships with food, eating disorder considered as a prototype for cutting, transient mental illnesses, Ian Hacking’s Mad Travelers, The Taming of Chance, train fugue, death rates and anorexia, disorders as a misunderstanding of control, exploring marriage through intimacy, Ted in “The Mother of My Children” compared with Greta’s husband in “A Walk to the Cemetery” and men in “Inside Madeleine,” sex as the defining quality of a relationship, the benefits of marriage, Jonathan Franzen’s thoughts on sex, the importance of bad sex scenes in narrative, Girls, Lena Dunham’s audience confrontation with body image, how the physical leads into the emotional, Dr. Ruth, sex described on 1980s radio vs. the ubiquity of Internet porn in 2014, setting stories in Boston and South Bend, Indiana, writers who have to wait ten years to revisit material, writing material intermittently over very long periods of time, whether stories set at home are easier to finish, writing Baby over a long period of time, Bomer’s idea folder, “Outsiders” and Bomer’s boarding school story aspirations, memories as ways to trigger imaginations, Bomer’s unpublished novel set in Berlin, the difficulty of setting a story in a place you’ve never gone to, Christina Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children, Annie Proulx vs. Richard Ford on being a stickler for location vs. making place up, locational accuracy as an act of preservation, getting the reader to believe, the lifespan of a novel, being a young girl in the 1970s and the 1980s, being called a slut and slut shaming, hookup culture, literal blindness juxtaposed against other forms of blindness, when text isn’t enough to know what’s going on with characters, going through old papers and photographs, how anthropological texts became an unexpected muse, hoarding, contending with clutter, when tough people are internally fearful, the abstract nature of what we represent through writing, writing a story compared with painting a floor, how houses become interesting because of lazy interior decorating, the minor surrealism of “Breasts,” the 1998 animated short “More,” magical glints, Bomer’s upper limits of fantasy and magical realism, subjective magic as a method of revealing urban trappings, Samuel R. Delany’s idea of pornotopia, religion in “The Shitty Handshake,” “Lightning,” Bill Burr, Scientology vs. the Catholic religion, belief and fantasy, “Two Years,” subverting titillation, taking out various Sonyas in stories to preserve certain continuity threads from Nine Months, Philip Roth, being taken seriously while also going into uncomfortable places, Sabbath’s Theater, Chaucer’s ass-kissing in “The Miller’s Tale,” Dante and scatology, Ulysses, Germans and nudism, the human reality of walking around repressed, the carnal way that apes greet each other, using the word “compartmentalize” too much, literature as a vicarious outlet for reader and author, the class divide, Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the realities of class and capitalism, difficulties getting healthcare insurance, preexisting conditions, how dinner table political discussion stifles conversation, how swiftly Brooklyn has changed, Hal Ashby’s The Landlord, cab drivers who kicked you out of the car, subway muggings from decades ago, New York in the early ’90s, questioning why writers don’t get B-sides, being forced to move elsewhere because of the rich, and the alien notion of being in several stages of life so fast.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: One thing we didn’t actually discuss the last two times we chatted was your interest in the external. Many of your stories here feature side characters who have their skin pocked or acned or stretched or otherwise maimed in some sense. Anya has acne scars in “Reading to the Blind Girl.” You have Polly’s chicken pox scars in “Down the Alley.” There’s Maddy’s beginnings in “Inside Madeleine.” How much do you need to know a character physically before knowing her internally? How does a damaged physical appearance help you find unexpected internal qualities about a character? Are there any disadvantages or advantages in concentrating upon the external?

Bomer: I actually was greatly affected by an essay, or a nonfiction piece, by Flannery O’Connor, who complained about some other writers who she didn’t appreciate. Because she said, “I can’t see these people.” And then I was revisiting Flannery O’Connor and it seems quite simple. But you see her characters. And she explains how they look. It’s a little old-fashioned, but I think it works for this collection in particular. Especially dealing with external damage or how our bodies affect what’s going on inside of us. There’s a huge New Age movement about that. You have to do all these things inside your body to glow or whatever. But, yeah, interesting that you point out their scars and deformities. That too would be the “Grotesque in Southern Fiction” essay of Flannery O’Connor. And I was unware until you pointed that out. But now that you’ve pointed that out, oh, that is a theme

Correspondent: But I am curious to get into this notion of how a character looks. I’ve actually been discussing this quite a bit this year with authors — especially in relation to sustaining a mystery. How you see in mysteries that you don’t really know the protagonist, how the protagonist looks like or what not. And that’s part of the way of getting inside the character internally. And I’m wondering what motivates your need to really see them externally before you can see them internally. Do you think there’s a kind of mystery or a tension here sometimes when you’re advancing a story?

Bomer: Well, I hope there is mystery, not necessarily the classical mystery novel, but definitely you want to be discovering things in a story as you go along. And I hope I can accomplish that. I don’t know — I’m thinking of the story “Cleveland Circle House.” That story came to me and the opening is all about how she looks. Like her neck’s too big, her chin’s too long. I can’t remember exactly. But that story came to me first with this young girl’s face and how one person loves her for it and thinks she’s amazing and another person doesn’t think much of her at all. Like her parents, in other words, have this very different reaction to who she is physically and as a person. So that started the story.

Correspondent: Much as the back started “Inside Madeleine”? The back of the mother at the very beginning.

Bomer: Oh yeah.

Correspondent: I love the way you fixated on a physical part like that.

Bomer: Yeah. And the dynamic being she’s always there with her mother’s back. That weird separation and how they’re trying to bridge that separation by feeding. That was very obviously something I was trying to do and I did it in a repetitive, somewhat experimental way. Not as traditionally structured narrative.

Correspondent: It’s weird. Because the beginning of that story made me think of a Dorothea Lange photo for some reason. The hardened back. I was thinking, “Gosh, if we see her face, will she look like something out of the Dust Bowl?” (laughs)

Bomer: That’s pretty funny. I don’t think we ever really see her face.

Correspondent: No, we don’t!

Bomer: No.

Correspondent: I’m telling you. There is mystery here!

Bomer: (laughs) So when mysteries — I’m not as well-read in mystery as you are, but I do know that Jim Thompson, who I don’t know if you’d call — I guess he’s more noir.

Correspondent: I call everything “literature” myself.

Bomer: Yes.

Correspondent: It just happens to be categorized in the mystery section sometimes.

Bomer: Right. I’m with you. But Jim Thompson, you see his characters, although all the male characters, I’m thinking now, kind of blend together. But the women are specific. One of my favorite is how she’s really beautiful but she has long gray hair and he’s dealing with all these weird Freudian mom issues, like he often does in his stories. Her looks are a very big part of her character and his relationship to her and how he likes the fact that she’s got long gray hair, even though she’s also very young and sexual in a way. So the dichotomy of that. I guess I think that drawing, getting an idea of what people look like — weight issues are a big part of it. This book deals with the external and how it affects our place in the world. Polly, with her going through puberty, which is a horrible time and all you care about is what people think about how you look when you’re twelve.

Correspondent: Well, I mean, this leads me to wonder if external description is almost a mere…

[DOG BARKS]

Bomer: Sorry, guys.

Correspondent: It’s okay. We can have a few dogs bark on this podcast. Keeps the tension going. It makes me wonder if external description is in some sense almost a mirror that you can hold up to the reader, as an author, to confront either the world or to confront the notion or the worldview the reader brings into your stories. Is that safe to say?

Bomer: Yeah. I would hope so. That would be wonderful. Because I definitely put thought into how I’m describing them, what I decide to focus on, and it affects how they are seen in the world and accepted by their communities or relationship with their professor. The one you mentioned, Anya, the fact that she has pock marks endears her. It makes her vulnerable to the student and makes the student feel that she can bridge this teacher-student gap, and really have an intense friendship almost with this woman. Or at least lean on her in ways that are very gratifying. And that’s definitely — I have something where I love vulnerability in people. So basically I project that in various ways throughout all of my books. But maybe this one, because they’re all kind of coming of age, they’re in that really more insecure phase in many ways.

Correspondent: Well, that’s interesting. We have a teacher/student dynamic. But there’s also a student/student dynamic in many of these college stories. So you almost have to have two dynamics to get inside what these protagonists are dealing with. I’m wondering how that kind of relationship developed in the blind girl story and also “Cleveland Circle” as well.

Bomer: Yeah. Well, definitely a theme that I’m exploring throughout this is young women, or girls, and their relationship to other young women and girls. I don’t paint a pretty picture, I’m afraid. And even thought there is…it’s not all bad. But most people I know throughout their lives, they’re going to discard some relationships. And those relationships, because they’re…oh god, I was going to say toxic. And that’s so cheesy.

Correspondent: Well, “toxic” we can use.

Bomer: But I think there’s a book called Toxic People.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Bomer: This whole silly psychology.

Correspondent: Why is toxic cliche now? I’m curious.

Bomer: Because of a book, right? It’s like the “inner child.”

Correspondent: Well, “toxic” isn’t on that level of “inner child.”

Bomer: Okay. I hope. Maybe.

Correspondent: We can use it during the course of this conversation. It’s okay.

Bomer: Okay. I appreciate it.

Correspondent: You can use anything.

Bomer: Using the word “toxic.” I’m actually trying to think of another way of describing it. But one thing for certain is that I do believe — so this is another psychobabbly thing — when you’re young, you’re kind of reliving relationships, maybe even your family relationships. And you kind of seek out the person who’s going to be some of the negative things that happened at home. And I’m not saying that everyone is completely damaged or whatever. But most people have some bumps in life, in their family, in their social life. And then I take it to a bit of an extreme. Because to me, that’s more interesting from a literary standpoint. And I don’t always. But in this book, I would say a lot of it is quite extreme. And definitely these characters, a lot of them are attracted to these people who aren’t very nice to them and who they either worship. Because they have things that are small or are skinny or they seem confident. And then they end up getting kind of hurt by that situation. Or the opposite, the occasional “Oh, this person’s vulnerable and therefore I can be vulnerable around them.” And so there’s this safety in relationships.

Correspondent: You’re sort of suggesting that people are looking for a new family when they go to school. And this is the great fluid organizational structure that you can bring into narrative, which requires organizational structure.

Bomer: Yeah. Definitely. That’s a very good way of looking at what I’m trying to do, in particular with this book.

(Photo credit: Robert Martin)

The Bat Segundo Show #546: Paula Bomer III (Download MP3)