Yiyun Li is most recently the author of Kinder Than Solitude. She previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #323.

Author: Yiyun Li

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: Moving on, sustaining characters who inhabit their own mystery while an overarching mystery exists to tantalize the reader, judgment of characters and simultaneous mystery, Edward Jones, working out every details of a story in advance, forethought and structure, the original two structures of Kinder Than Solitude, creating a structure alternating between the past and the present, thinking about a project for two years before writing, William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, time as a collage structure, photographs as a marker of identity, not really knowing what the characters look like in Kinder Than Solitude, why Li didn’t visually describe her characters, being an internal writer and reader, writing from inside the characters, Ian Rankin not describing Rebus over the course of more than twenty novels, Patricia Highsmith, Joan Schenkar’s The Talented Miss Highsmith, Tom Ripley’s manipulative nature, the dangers of general comments, problems when literary fiction describes objects in consummate detail instead of emotions, freedom and the courage to write about a character’s soul, Chinese Catholics who practiced in secret, priests executed as counterrevolutionaries in Communist-controlled China, underground faith and literary relationships, inevitable bifurcation in exploring an absolute, having to ask the question of whether a sentence is true before setting it down, questioning yourself in everything you do, the allure of family (and the impulse to run away from it), the mantras and maxims that flow through Kinder Than Solitude, coating truth in wise and optimistic sayings, the beauty and sharp internal emotions contained within Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart, subtlety and shock in relation to internal character examination, poison as a passive-aggressive form of murder, poison as a muse, Li’s accordion skills (and other revelations), the current American accordion player crisis, “I find your lack of faith disturbing” in Star Wars, when any idea (such as “bok choy”) can be sandwiched into political ideology, notions of planned economy in 1989 China, the personal and the politically being ineluctably intertwined, exploring prohibitions on American political fiction (also discussed in Dinaw Mengestu interview), James Alan McPherson‘s “Elbow Room,” contemplating why Americans are being more careful in discussing the uncomfortable, how the need to belong often overshadows the need to talk, Communist propaganda vs. digital pressures, extraordinary conversations in Europe, considering what forms of storytelling can encourage people to talk about important issues, William Trevor, the intertwined spirit and freedom of Southern literature, Carson McCullers, the flexibility of literary heritage, notions of New South writing, regional assignation as an overstated tag of literature, establishing liminal space through place to explore flexibility in time, despair without geography, feelings and time as key qualities of fiction, writing love letters to cities, James Joyce having to go to Trieste to write about Dublin, and whether place needs to be dead in order to make it alive on the page.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: There’s this point in the book where Moran says to Joseph, “Moving on? That’s an American thing I don’t believe in.” And then there’s this moment late in the book where one American is utterly devastated by what she learns about one of the characters. I’ll try not to give it away. All of the inferences she made are essentially thrown back into her face. And I think this novel dramatizes belief culture in very interesting ways. I’m wondering. How is belief formed or reified by a national instinct, whether it is American or Chinese? And how do you think the migratory impulse of “moving on” causes us to believe in people in very harmful ways? How does this affect you as a novelist? Someone who is asking the reader to believe in lies. Just to start off here.

Li: Right. You know, it’s interesting. Because I always say “moving on” is an American concept. The reason I said that was that, right after 9/11, I was so impressed. By the two months after 9/11. All the newspapers were talking about “moving on.” Americans should move on. And for me, that was quite incredible. Because I did not understand what “moving on” meant and that concept.

Correspondent: This is your introduction to “moving on.”

Li: Yes. And so it stuck with me. And of course, Moran borrowed that concept or Moran said “moving on” after 9/11. People talked about moving on. But the national belief, it’s interesting because I think this Western concept of “moving on,” you know, there’s always a second chance. There are always more opportunities in front of you if you just get over this hurdle. Now it’s becoming more an Asian thing. Only in the past maybe three or four years. If you look at not only China but Southeast Asia, Malaysia, Singapore, all these countries start to believe in moving on. We’re not going to stay in any moment. We’re just going to catch this wave of being.

Correspondent: You left out North Korea. (laughs)

Li: (laughs) Oh no. They can’t. So to me, that’s interesting. Because that’s a belief that, as people are migrating from East to the West, ideas are migrating from the West to the East. And, of course, people coming to America are returning to Asia. So there are these waves of ideas. So now, if you look at Chinese or other Asian countries, “moving on” is a big thing. You know, we’re not going to get stuck in a Cultural Revolution. We’re not going to get stuck in Tienanmen Square. We’re just going to move on to be rich.

Correspondent: But the thing about moving on, I mean, it’s used in two senses. You allude to this American impulse of, yes, well we can move on and have a second chance and start our life over. But there’s also this idea of moving on as if we have no sense of the past. That we have no collective memory or even individual memory. And I’m wondering, if it’s increasingly becoming a way to identify the East and the West, is it essentially a flawed notion? Or is it a notion that one should essentially adopt and then discard? Because we get dangerously close into believing in illusion?

Li: Right. I would feel suspicious of any belief and, again, as you said, moving on really requires us to say we’re going to box this kind of memory. We’re going to put them away so we can do something else. And, of course, as a novelist or as a writer, you always feel suspicious when those things happen. Because you’re manipulating memories. You’re manipulating time.

Correspondent: You’re manipulating readers.

Li: Yes.

Correspondent: So in a sense, you become an ideologue as well.

Li: Exactly. So I would say that anytime anyone says, “Let’s move on” or “Let’s look at history all the time,” I would become suspicious. Because both ways are ways to manipulate readers or characters.

Correspondent: So it’s almost as if you have to dramatize belief culture to be an honest novelist. Would you say that’s the case?

Li: Well, I would say it’s to question that belief culture. And I think when you question, there are many ways to question. To dramatize is one way to question. I mean, you can write essays. I can write nonfiction to question these things, but, as a fiction writer, I think I question the belief culture more than dramatizing it.

Correspondent: How do you think fiction allows the reader to question belief culture more than nonfiction? Or perhaps in a way that nonfiction can’t possibly do?

Li: I think they do different things. For instance, I’m not an experienced nonfiction writer. I do write nonfiction.

Correspondent: You can approach this question from the reader and the writer viewpoint too.

Li: I think for me the most important thing to ask as a fiction writer is you don’t judge your characters. So if they’re flawed in their belief culture, you let them be in that culture and do all the things so that the readers can come to their own conclusions. In nonfiction, I feel that a writer needs to take a stand probably more than a fiction writer.

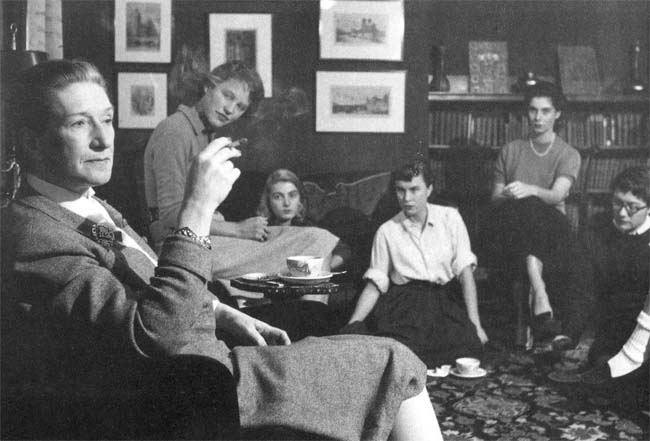

(Photo: Karin Higgins)

(Loops for this program provided by danke, ozzi, decibel, michiel56, and OzoneOfficial. )

The Bat Segundo Show #542: Yiyun Li II (Download MP3)