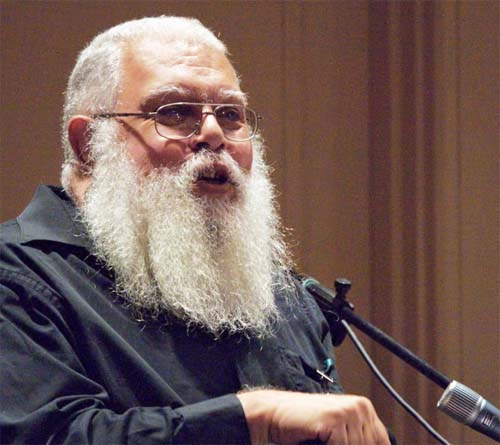

Sameul R. Delany appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #459. He is most recently the author of Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Growing a beard to make up for lost time.

Author: Samuel R. Delany

Subjects Discussed: Literary beards, spending the same amount of money on books as food, how many books Delany has read, developing a cataract, Jason Rohrer’s Passage, the structure of Spiders, time moving faster as you get older, Delany’s academic career, the amount of sex contained within Spiders, the male climacteric, how the body changes, About Writing, including a short story in a novel, the original version of Spiders in Black Clock, seven years contained within the first 400 pages, E.M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel and fleshing out the idea of “writing what you know,” Lear and “runcible,” Times Square Red Times Square Blue, the Dump vs. the Deuce, the pre-1995 porn theaters in Times Square, transplanting New York subcultures to Georgia, the importance of institutional support to a community, gay conservatives, inventing the Kyle Foundation, Goethe’s Elective Affinities, Steven Shaviro’s thoughts on Delany’s intensities, transgressive behavior, connections between The Mad Man and Spiders, pornutopic fantasies, Hogg, when pornotopia sometimes happens in reality, Fifty Shades of Grey, balancing the real and the fantastical in sexual fiction, Delany’s usage of “ass” and “butt,” how dogs have orgasms, making a phone call in the middle of dinner to find out about sexual deviancy, why Shit does a lot of grinning, Freu and infantile sexuality, the paternal thrust to Shit and Eric’s relationship in Spiders, the difficulty of reading Spinoza’s Ethica, whether a philosophical volume can replace the Bible, living a life driven by one book, Hegel, Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, movies vs. books, interclass conflict, Peter Jackson’s films, how mainstream culture relates to subcultures, Jackson’s original notion of the King Kong remake as Wagnerian ambition, Tristran and Isolde, turning up the idealism dial, whether art can live up to pure ambition, the myth of the wonder decade, living through the 50s and 60s, Freedom Rides, people who are diaphanous to the forces of history, the Beatles, peasant indifference during the Dreyfus affair, the impact of not knowing the cultural canon, nanotechnology, John Dos Passos, fiction which responds to present events, life within California, living in San Francisco, how Market Street has changed, assaults on the homeless in San Francisco, the Matrix I and II programs, the gentrification of the Tenderloin, novels of ideas, whether or not genre labels hold conceptual novels hostage, market conditions that hold ambitious fiction back, Delany’s nine apprentice novels, trunk novels, and editorial compromise.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: There’s this video game art project called Passage by Jason Rohrer. Have you heard of this?

Delany: No.

Correspondent: Okay. Because your book reminded me very much of this.

Delany: Really?

Correspondent: I’ll have to forward you the link. Basically, it’s this sidescroller. It’s in a 100 pixel by, I think, 13 pixel window. And you control this person who goes from left to right. From beginning to end of life. And you pick up a partner. In fact, you grow a beard.

Delany: (laughs)

Correspondent: And you die at the end. And it takes the 8-bit sidescroller and it turns it into this unexpectedly poignant moment. If you play it enough times, you can move the cursor down and actually have the figure go into this mire and collect stars, but maybe not have a partner or maybe meet an early demise there. And it absolutely reflects what life is. And I read your book, and I was extremely aware of the physicality. Not just because it was an 800 page book, but because the first 400 pages is basically these escapades of lots of sex, youthful brio, and so forth. And then, suddenly, decades flash by often when we read this. And I’m curious, just to start off here, where did the design of this structure come from? I know you’re very keen on structures. You’ve written about this many times. But how did this come about in Spiders?

Delany: Well, it came from being a person who’s gotten older. I just had my 70th birthday.

Correspondent: Yes. Happy birthday.

Delany: Thank you very much. And one of the things that does happen, and it’s a really interesting phenomena, is that time seems to go a lot faster as you get older. When you were young, time takes forever. You go to the doctor. You wait around for two hours in the doctor’s office. It seems like three months. Whereas I went to the doctor’s office this morning. I went in. And the next thing I knew, I was on my way here. And I’d been there about two and a half hours. And it didn’t seem that any time had passed at all. And I was at the University of Massachusetts between 1988 and 1999, for eleven years. And that seemed much longer than the last twelve years, thirteen years, that I’d been at Temple University, where I’ve been there from 1999 to this year, 2012. And that seems much shorter than the eleven years that I was at UMass. And there’s no way to avoid this. As you get older and older, time just begins to rush by. And I wanted to get this. So actually, the time goes faster and faster through the book. But at a certain point, you realize, “Oh wait a minute! It’s rushing along.” As one of the reviewers said, decades drop out between paragraphs. Well, that’s what happens. That’s how your life kind of goes. So in that sense, the structure of the book is based on the structure of my own experience.

Correspondent: What’s very strange though — I read the book and, actually, I started missing the sex after that 400 page mark. I mean, all of a sudden, wait a minute, they’re not having so much sex anymore. There isn’t all the snot stuff and the pissing and the corprophiia and, of course, the father-son stuff. All of a sudden, we don’t have a lot of that at all. And then you drop some, quite literally, serious bombs later on in the book. And this leads me to ask…

Delany: Well, the sex doesn’t vanish.

Correspondent: Well, of course. It’s there. It keeps going on.

Delany: I mean, the sex is there. But it’s the sex that someone older has. And one of the things that they have to deal with is the fact that your body changes as you get older. And somewhere between 50 and 60, you go through the equivalent of the male climacteric. Which is a very strange thing to go through. Quite as odd…

Correspondent: Oh god. Thanks for warning me.

Delany: Quite as odd as, what is the term for women?

Correspondent: Menopause.

Delany: Menopause, yes. It’s very much like the menopause. And somehow you’re not warned. You aren’t warned how it’s going to change. Everybody notices the body changing. From ten to twenty, there are going to be a lot of changes. But there are going to be just as many changes from twenty to thirty, from thirty to forty, forty to fifty, fifty to sixty. You konw, I’ve been with my partner now, Dennis, for almost twenty-four years. And we still have a sex life. And we’re very fond of one another and very close. But it’s different. Things do change. And that’s one of the things that it’s about. I wanted to explore what the relationship of two men who were notably older was. And so I tried to do that.

Correspondent: You have said also in About Writing, which I’m probably going to be cribbing a lot from for this conversation, that a short story’s not exactly the best thing to include in a novel. And yet this book arose out of a short story that was published in Black Clock. Which leads me back to the original query. How did this thing become structured? How did this take on a life of its own?

Delany: Well, I had to throw away the whole second half of the original short story and rewrite something that flowed into the novel. If you actually compared it, the opening couple of scenes are very similar, although not identical by any means. There were lots of changes all through it. From the very first paragraph. But I wanted to use that as a kind of jumping off point.

Correspondent: Well, that’s one hell of a jumping off point. 800 pages. I mean, why do you think that you were interested in exploring such an expansive format? Why did Eric and Shit demand this sort of attention?

Delany: Well, because I wanted to talk about a lasting relationship between two men. And a very committed relationship. They’re very close to each other. They’re absolutely fixated on one another. I mean, neither one of them could really make it without the other. Which is the tragedy that Eric is faced with at the end. So I just wanted to explore that and see what happened, and deal with all these things. The time speeds up in the first half of the book too. The first 400 pages basically take, what, about seven years. So that’s even years. That’s a good Dickens novel. (laughs) But this is a book that goes on for basically sixty or seventy years.

Correspondent: Yeah. I wanted to also talk about the location. Since my name is Ed, I have to bring up another Ed. E.M. Forster. You have often quoted the advice given in Aspects of the Novel.

Delany: “Write what you know.”

Correspondent: “Write what you know.” But your idea here is to build upon that and say, in addition to writing what you know, it’s very good to keep the writing alive and energetic if you write about something that you’ve only experienced a few times.

Delany: Right. Exactly.

Correspondent: And in this, it’s interesting because it should be evident by your Lear-like use — another Ed — of “runcible” that this Georgia is a fantasy of sorts.

Delany: Yes. It’s a fairytale. The whole book is an 800 page fairytale.

Correspondent: Exactly.

Delany: By which I mean things like Don Quixote. (laughs)

Correspondent: Of course. But my question is: You’re almost writing what you know and you’re writing what you don’t know, or only know a little bit of. Because we have to go to Times Square Red Times Square Blue, which I also read. You write about a man in that named Tommy. He wears a sleeveless denim jacket. Well, there’s a guy with a sleeveless shirt here. And he collected scrap metal. Not unlike this. You look at The Dump. It could also be The Deuce. The Opera House. It could also be the Metropolitan Opera House.

Delany: Easily. Well, it wouldn’t be the Metropolitan. But it could be one of the old porn theaters before ’95. Before New York closed them down.

Correspondent: I guess my question though is: by putting much of these viewpoints that you have raised both in your fiction and your nonfiction to Georgia, to the edge of the earth quite literally, I mean, what does this allow you to do as a fiction writer? How does this allow you to explore a subculture that, say, keeping everything in New York would not?

Delany: Well, one of the things that I wanted to show is that the kind of life that Eric and Morgan — his nickname is Shit.

Correspondent: You can say “Shit” here.

Delany: That Eric and Shit lead — as I said, besides being a fairytale, is also — well, I’m trying to figure out a good way to put this. In some ways, it’s kind of didactic. It’s almost like a Bildungsroman. They have to learn how to live their life. And it can’t be done — and this is, I really feel — and this is one of the reasons why it had to be a fairytale — it needs institutional support. Which is why there has to be the Kyle Foundation and why there has to be a certain support, a certain community support for what they’re doing. And at the same time, they’re very much on the margin of this community. They’re not in the center of this community. So that people like Mr. Potts, for instance. A very conservative man who just doesn’t want his nephew, who has come down to spend the winter with him, associating with these riffraff who use the gay-friendly restroom. Because he doesn’t like the idea of gay men using the restrooms at all.

Correspondent: Where did the Kyle Foundation come from?

Delany: It was purely out of my head.

Correspondent: Really. Because there’s a specific phrasing in their mantra: “an institution dedicated to the betterment of the lives of black gay men and of those of all races and creeds connected to them by elective and non-elective affinities.” And that phrasing recalls any number of Islamic foundations and the like.

Delany: And also the Goethe novel.

Correspondent: Yes!

Delany: Elective Affinities.

Correspondent: So that was really more where it came from?

Delany: It came more from Goethe than it did from Islam.

Correspondent: Sure. Steven Shaviro. He has pointed out that the intensities of your pornography are never presented as transgressive. Now in a disclaimer…

Delany: Although this is pretty transgressive.

Correspondent: Well, of course. I want to talk about this. Because in a disclaimer to The Mad Man, of which we see statues of something that crops up in there appearing in this, you called The Mad Man “a pornotopic fantasy: a set of people, incidents, places, and relations among them that never happened and could not happen for any number of surely self-evident reasons.” Well, there is no such disclaimer for Spiders and we see much of the same stuff, as I said. Piss-drinking, shit-eating, you name it. I’m wondering. How does a pornotopic fantasy — how does one of these, whether it be The Mad Man or Spiders or even the infamous Hogg, how does this help us to understand or come to terms with the realities of sex and what the present limits are? What some people might call deviancy today or perhaps yesterday.

Delany: Well, literature is divided into genres like that. You have the world of comedy, the world of tragedy. And you have the world of pornography. And each of them is a kind of subgenre. And sometimes they can be mixed. You can go from one to the other. And I think pornotopia is the place, as I’ve written about, where the major qualities — the major aspect of pornotopia, it’s a place where any relation, if you put enough pressure on it, can suddenly become sexual. You walk into the reception area of the office and you look at the secretary and the secretary looks at you and the next minute you’re screwing on the desk. That’s pornotopia. Which, every once in a while, actually happens. But it doesn’t happen at the density.

Correspondent: Frequency.

Delany: At the frequency that it happens in pornotopia. In pornotopia, it happens nonstop. And yet some people are able to write about that sort of thing relatively realistically. And some people aren’t. Something like Fifty Shades of Grey is not a very realistic account.

Correspondent: I’m sure you’ve read that by now.

Delany: I’ve read about five pages.

Correspondent: And it was enough for you to throw against the wall?

Delany: No. I didn’t throw it. I just thought it was hysterically funny. But because the writer doesn’t use it to make any real observations on the world that is the case, you know, it’s ho-hum.

Correspondent: How do we hook those moms who were so driven to Fifty Shades of Grey on, say, something like this?

Delany: I don’t think you’re going to. I think the realistic — and there’s a lot that’s relatively realistic about it and there’s also a lot that isn’t. Probably less so in this book than in, let’s say, The Mad Man, which probably has a higher proportion of realism to fantasy.

Correspondent: I also wanted to ask you — what’s interesting is that there is almost a limit to the level of pornography in this. There’s one funeral scene where something is going to happen and they say, “Nuh-uh. You’re not allowed to do that. Show some respect.” And roughly around the 300 page mark, I was very conscious of the fact that you didn’t actually use the word “ass.” And you were always using “butt.” (laughs)

Delany: I didn’t even notice.

Correspondent: And so when “ass” showed up, I was actually shocked by that. So I’m wondering. Does any exploration of sexual behavior, outlandish sexual behavior or sexual behavior that’s outside the norms of what could possibly happen, whether it be frequency or density or what not — does it require limits with which to look at it? With which to see it in purely fantastical terms?

Delany: Well, I think one of the things that you need to write a book, especially a book this long, is you need a certain amount of variety. And I think that this is perhaps a failing. There are only so many things that you can do. I think I give a good sampling of them. But every once in a while, I’m sure it probably gets somewhat repetitious.

Correspondent: Well, it’s a good variety pack. But it’s also: “Okay, reader, you have to get beyond these first 350 pages and then, by then, you are actually able to get into totally unanticipated territory and I’ve already locked you in.” How did you work that out?

Delany: One of the things is that you try and keep telling interesting things about the sex. I mean, things that can be observed about the world that is the case. I mean, I tried to talk about the sex in terms of — I don’t think most people know how a dog has an orgasm.

Correspondent: How do we find this out? (laughs)

Delany: Uh, there’s a wonderful website. (laughs)

Correspondent: (laughs)

(Image: Ed Gaillard)

The Bat Segundo Show #459: Samuel R. Delany (Download MP3)

Williams: We all have these substances coursing through our bodies. Unfortunately, some of them really collect in fatty tissue in the breast. And then the breast is really masterful at converting these substances into food. So it ends up in our breast milk. But I would point out that I did continue breastfeeding. I was convinced that the benefits still outweighed the risks. And, of course, formula is not a completely pure product either. It’s also contaminated with heavy metals and pesticides and whatever else is in the water that you’re mixing it with. And then, you know, of course there are sometimes these

Williams: We all have these substances coursing through our bodies. Unfortunately, some of them really collect in fatty tissue in the breast. And then the breast is really masterful at converting these substances into food. So it ends up in our breast milk. But I would point out that I did continue breastfeeding. I was convinced that the benefits still outweighed the risks. And, of course, formula is not a completely pure product either. It’s also contaminated with heavy metals and pesticides and whatever else is in the water that you’re mixing it with. And then, you know, of course there are sometimes these