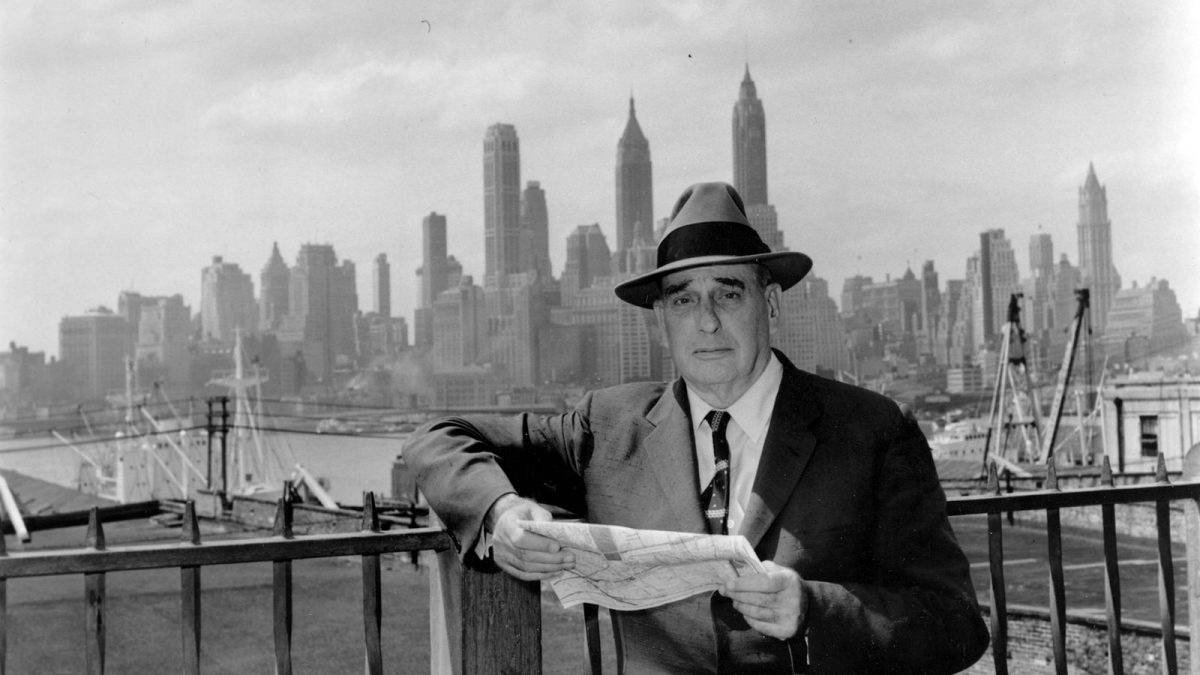

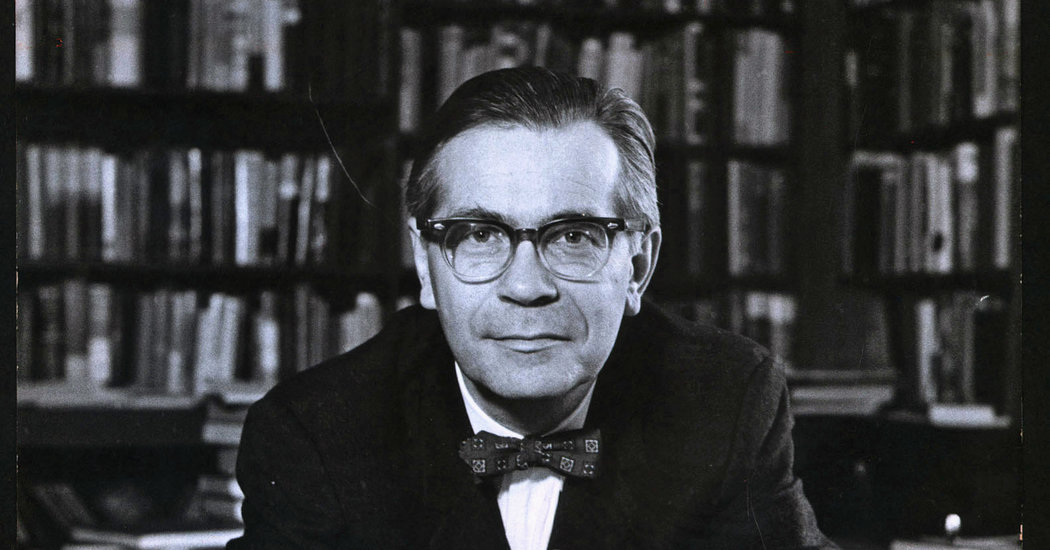

Robert A. Caro appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #455. He is most recently the author of The Passage of Power.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Expressing his determination to keep the forward thrust of America began with notable historians.

Author: Robert A. Caro

Subjects Discussed: Lyndon B. Johnson as a great reader of men, Horace Busby, Johnson talking with people until he got what he wanted, Johnson’s misread of John F. Kennedy, the 1960 Presidential Election and Johnson’s self-sabotage streak in seeking the nomination, Emmett Till and Autherine Lucy, passing the 1957 Civil Rights Act, Jack Kennedy’s use of television, Johnson having his staff calculate the odds of a U.S. President dying in office, “power is where power goes,” Sam Rayburn, Johnson’s mode of desperation vs. Steve Jobs’s “reality distortion field,” Southerners as Presidents, Johnson’s decisiveness in the Senate, John Connally, Johnson’s fear of failure, Sam Houston, Johnson not wanting to be like his father, Johnson’s inability to stare physical reality in the face, smoking and fluctuating weight, challenging Arthur Schlesinger, Johnson being shut out from many of the key Kennedy meetings as Vice President, Johnson’s humiliations, LBJ being reduced to a “salesman for the administration,” the spiteful rivalry between Robert Kennedy and LBJ, character being a defining quality of politics, the importance of vote counting in Washington, Johnson as Senate Majority Leader, Johnson’s preying upon the loneliness of old men, Richard Russell, the Armed Service Committee, Johnson’s manipulation of Russell on civil rights and the Warren Commission, how Southern Senators were duped into believing that Johnson was against civil rights, the phone call in which Johnson forced Russell into the Warren Commission, how Johnson preyed on older men to get what he wanted, Kennedy’s tax bill, how Johnson worked on Harry Byrd, how Johnson dealt with human beings, the impact of personality on policy, Johnson’s terrible treatment of Pierre Salinger, Johnson bullying his subordinates, what Caro found the hardest to write about, triumphs of willpower, Johnson’s involvement with Bobby Baker, the Bobby Baker scandal, the surprising sensitivity with which the media handled Johnson’s corruption after the Kennedy assassination, the Life investigative team on Johnson (as well as Senate investigation), the lowering of the Presidency because of Johnson, some hints about Volume V, and Johnson’s legacy.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: You challenge in this book Arthur Schlesigner’s long-standing notion about the relation between Kennedy and Johnson. Now Johnson is in the vice presidential seat. Schelsinger’s idea was that, well, Kennedy was absolutely fond, genial, and generous. The vice president was included in most of the major meetings. And then, of course, we read this chapter “Genuine Warmth” and we find out, well, wait a minute! That’s not always the case. According to Ted Sorenson, Johnson was shut out from a pivotal ExCom decision, a decision meeting relating to the Cuban Missile Crisis. And that also is in large part because Johnson is a bit hawkish to say the least. So my question is: why has the lens of history been so keen to favor the Schlesigner viewpoint? And what was the first key fact that you uncovered that made you say to yourself, “Well, this isn’t exactly true”? What caused you to start prying further and further? That caused you to think, well, things are not all wine and roses.

Caro: Well, you know, part of it was that as soon as you start to look at Johnson and the Kennedys, you hear about the nickname that the Kennedy people called him. “Rufus Cornpone.”

Correspondent: That’s right.

Caro: “Uncle Cornpone.” “Uncle Rufus.” You know, they coined phrases for Lyndon Johnson and Lady Bird. They used to call them “Uncle Cornpone and His Little Pork Chop.” Then you ask someone like Ted Sorensen, who helped me immensely. He was the person probably closest to Kennedy in the administration.

Correspondent: You spent a lot of time with him.

Caro: I spent a lot of time with Ted. And he said, yes, as has previously been said, Johnson was included in all the big meetings, the Cabinet meetings, the National Security meetings. But in the Kennedy government, those weren’t the meetings that mattered. The meetings that mattered were the small little groups that Kennedy would convene. And Johnson wasn’t invited to those. You know, when the 1963 Civil Rights Act is introduced by the Kennedys and Johnson has to say to Ted Sorensen — we happen to have a recording — “You know, I don’t know what’s in this act. I have to read about it in The New York Times.” The greatest legislator possibly of the century, the greatest legislator of the 20th century is not consulted on Kennedy’s legislation.

Correspondent: Why then has the Schlesinger lens been allowed to proliferate for so long? That’s the real question.

Caro: Well, I don’t know that it’s just the Schlesinger lens.

Correspondent: Or this idea.

Caro: I really can’t answer that question. But when you talk to the surviving Kennedy people — like Sorensen — when you read their oral histories, you see it’s simply not true. I mean, Horace Busby talks basically about going to see Sorensen one day and asking, “Well, what role do you want Lyndon Johnson to play in this administration?” And Sorensen says, “Salesman for the administration.” I mean, this is Lyndon Johnson, who is to be the salesman for the administration. Johnson says to an aide, Harry McPherson — you know, they’ve turned the legislative duties over to Larry O’Brien. Johnson says, “You know, O’Brien hasn’t been to see me to ask advice once in two years.” So it’s undeniable that Johnson was shut out from Kennedy’s legislative processes and from the Cuban Missile Crisis — the key meeting of the Cuban Missile Crisis. He’s not invited to it.

Correspondent: I know. It’s really amazing. One of the other great showdowns in this book — the great clash is between Bobby Kennedy and Johnson. I mean, you want to talk about cats and dogs, these two guys were it. You have their first meeting in the Senate cafeteria in 1953 where Kennedy was glowering at Johnson and forced to shake his hand. Then years later, Johnson is Vice President. And he’s largely powerless as we’ve been establishing here. He serves on the Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity. And Bobby Kennedy shows up late, humiliates him over two meetings.

Caro: Yeah.

Correspondent: And then on the Saturday after the Kennedy assassination, there’s this misunderstanding over how the West Wing is going to be cleared out and ready for Johnson. There’s this very tense meeting not long after. But Johnson is in this interesting predicament of having to maintain the Kennedy faction all through Election Day in 1964. Yet he also tests the waters a bit with the Thomas Mann nomination. So my question is: was there any hope of Bobby Kennedy and Johnson putting aside their differences? What factors do you think caused Bobby to acquiesce to Johnson for the good of the nation while Johnson was President?

Caro: Well, he doesn’t always acquiesce.

Correspondent: Sure.

Caro: We see him breaking with him strongly over Vietnam in 1967 and 1968 and running for the nomination. I mean, when Bobby Kennedy enters the race, Lyndon Johnson bows out basically. You know, people don’t understand, in my opinion, enough. And I try to explain in my books how personality, how character, has so much to do with politics and government. And with Robert Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, whatever the reasons are, at bottom you have this personal hostility. You talked about the first meeting. You know, this first meeting is when Lyndon Johnson is the Leader. He is the mighty Leader. Bobby Kennedy — I think he’s 27. And he’s just gone to work for Senator Joe McCarthy as a staffer. So Joe McCarthy — the Senate cafeteria is on the second floor of the Senate Office Building. And every morning, Johnson goes in there to have breakfast with his aides. And Joe McCarthy is sitting every morning at this big round table near the cashier with four or five or six of his aides, you know. And every time Johnson comes in, McCarthy jumps up as everyone does to Johnson and says, “Hello, Mister Leader. Can I have a few moments of your time, Mr. Leader? Good work yesterday, Mr. Leader.” One morning, there’s a new staffer there. It’s Robert Kennedy. Johnson walked over. Senator McCarthy jumps up. And so, as always, do all his staffers. Except one. Robert Kennedy, his 27-year-old staffer, sits there glaring at Johnson. Johnson knows how to handle situations like this. He holds out his hand to everybody sort of halfway out and forces Bobby Kennedy to stand up and take his hand. And George Reedy said to me — I said, “What was behind that?” George Reedy said, “You know, you ever see two dogs come into a room that never met each other and the hair rises on the back of their neck immediately and there’s a low growl?” That was the relationship between Bobby Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Of course, there were other reasons. Robert Kennedy was very attached and devoted to his father, Joseph Kennedy.

Correspondent: Sure.

Caro: And Johnson, who was close to Roosevelt, was always repeating these stories about Roosevelt firing Joe Kennedy, tricking him into coming back to Washington from England, and then firing him. Making him look bad. So I think that Robert Kennedy hated him for that. But it’s not too strong a word to use hatred for what was going on between Bobby Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. And, you know, at the convention, one of Johnson’s assistants, Bobby Baker, he thinks everything’s just politics. So he’s having breakfast in a coffee shop in Los Angeles at the convention. He sees Bobby Kennedy come in and says, “How about sitting down?” He’s Bobby Baker, sitting with his wife, having breakfast. Bobby Kennedy sits down. But within two minutes, he’s up. And he throws money on the table. And he says to Baker, “Don’t worry. You’ll get yours when the time comes.” Well, the time came. Johnson was Jack Kennedy’s Vice President. Bobby Kennedy has, in effect, power over him. And he makes life miserable for Lyndon Johnson.

Correspondent: What you said at the beginning of this, about character being a defining quality of politics. I mean, Johnson, as you establish in this book and in Master of the Senate, is a master vote counter. He has his tally sheets when he’s in the Senate. He’s going ahead and making sure he knows exactly how things line up. In this book, you point out during the wheat bill that not only does he want enough votes to make the wheat bill [an amendment from Sen. Karl Mundt banning sale of surplus wheat from Russia] die. He wants it murdered, as he says. So the question I have. He may have been a master vote counter. But how much character did he need to go along with that? Was vote counting enough for him? Was that relentless drive just as much of a quality as the sheer statistician approach that he had?

Caro: It was never a sheer statistician, of course.

Correspondent: Of course.

Caro: He was a great legislator. Listen. A key thing in politics is the ability to count. And Johnson was the great counter. He’d send aides to find out how senators were going to vote. So sometimes someone would come back. Usually they didn’t do this more. They said, “I think Senator X is going to vote this way.” Johnson would say, “What good is thinking to me? I need to know.” He never wanted to lose a vote. So vote counting. He was the great vote counter. He’s a young Congressman. He comes to Washington. He’s 29 years old. He falls in with this group of New Dealers, who later become famous. Abe Fortas. Jim Rowe. “Tommy the Cork” Corcoran. These are guys who live and breathe politics. And do you know what they do when they have a dinner party on Saturday night? They get together for dinner. They count votes. They say, “How is Roosevelt’s bill on this going to be?” And Johnson, they said, was always right. We might think this Senator was going to vote this way. Johnson always knew. He was the greatest vote counter. And when he was in the Senate, he was the greatest vote counter of them all. But that’s not all of why Johnson was great. Johnson was this master on the Senate floor. He got through amendments. And there’s the base. And there’s shouting back and forth. He can seize the moment. He sees the moment where he can win. And he acts decisively. He says, “Call the vote.” And he’s Majority Leader. And he would stand there at the Majority Leader’s desk. So he’s towering over everybody else’s front row center desk. He’s got this big arm in the air. And if he’s got the votes, he wants the vote fast before anyone can change. Or maybe some other people on the other side are absent and not there. He makes little circles on his hands, like someone revving up an airplane, to get the clerk to call the rolls faster. And if one of his votes wasn’t there, and he was being rushed from somewhere in a car across Washington, he would make a stretching motion with his hands. He ran this. There were a lot of things that went into Johnson’s dominance of the Senate.

The Bat Segundo Show #455: Robert A. Caro (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced