“Don’t be so gloomy. After all, it’s not that awful. You know what the fellow said. In Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed. But they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love. They had five hundred years of democracy and peace. And what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.” — The Third Man

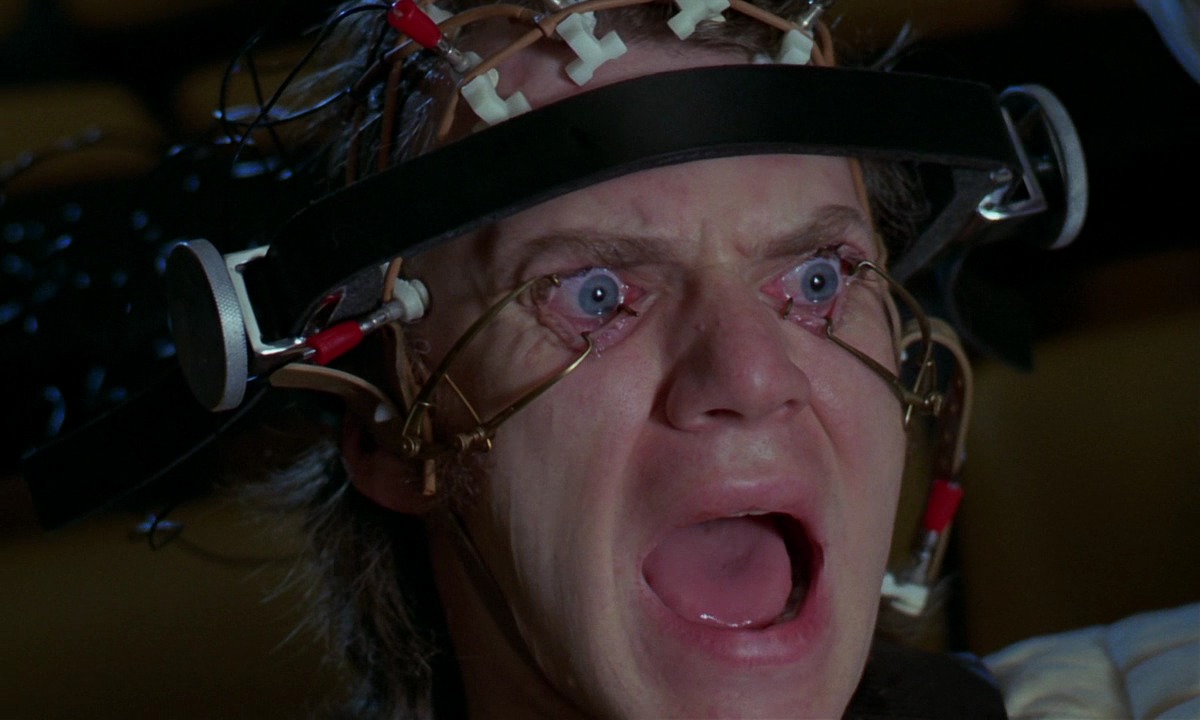

On February 26, 2014, a UC Santa Barbara student named Bailey Loverin pushed “A Resolution to Mandate Warnings for Triggering Content in Academic Settings” through the Associated Students Senate. The resolution called on professors to issue “trigger warnings” for students on “materials with mature content” taught in the classroom — whether it be a difficult film shown for context, material assigned for reading, or even a casual conversation on a tough issue. Loverin cited her own discomfort sitting through a film, one which she has refused to identify, depicting sexual assault. The class’s unnamed professor, according to Loverin, provided no warning before the film. Loverin claimed that it was harder for her to walk out of the movie, because doing so in the dark would apparently draw attention. (I have consulted other interviews with Loverin to establish the facts. Loverin did not return my emails for comment.)

Loverin has stated that she’s a survivor of sexual abuse, but she has not suffered from PTSD — the chief reason proffered for the “trigger warning” resolution. In an interview with Reason TV, Loverin said, “We were watching a film. And there were several scenes of sexual assault and, finally, a very drawn out rape scene. It did not trigger me. I recognized the potential for it to be very triggering.”

Loverin is not a psychologist, a sociologist, or a medical authority of any kind. She is a second-year literature major who has become an unlikely figure in a debate that threatens to diminish the future of free speech. Yet Loverin isn’t nearly as extreme in her views as the trigger warning acolytes at other universities.

Rutgers’s Philip Wythe has claimed that trigger warnings are needed for Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (for students suffering from self-harm) and for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (apparently a literary gorefest on the level of an episode of The Walking Dead). Oberlin threatened to issue trigger warnings over such traumatic issues as “heterosexism, cissexism, ableism, and other issues of oppression,” before the policy was sensibly pulled for further reconsideration.

Loverin claimed in an opinion roundtable for the New York Times that the UCSB resolution “only applies to in-class content like screenings or planned lectures and doesn’t ban the content or excuse students from learning it.” The resolution offers a suggested list of “rape, sexual assault, abuse, self-injurious behavior, suicide, graphic violence, pornography, kidnapping, and graphic depictions of gore” as trigger warning options. Students who feel that they “have a negative emotional response” (note that it is any “negative emotional response,” not necessarily PTSD) “to such content, including distressing flashbacks or memories, should be allowed to leave the classroom or skip class altogether without being penalized.” And while there certainly isn’t any direct prohibition, there is still the unsettling possibility of professors forced to soften their materials, which leads one to wonder how they can adequately teach war, genocide, slavery, or imperial conquest in the classroom. Another question, one that has remained unconsidered by trigger warning boosters, is whether or not skipping class over material that easily offends will be used as a catch-all excuse for students to shirk their scholarly duties.

In the Reason TV interview, Loverin said, “Being uncomfortable, being upset, being even a little offended is different than having a panic attack, blacking out, hyperventillating, screaming in a classroom, feeling like you’re under such physical threat, whether its real or perceived, that you act out violently in front of other people.” It certainly is. Yet there is no evidence to support Loverin’s claim that there is a widespread epidemic of students acting out violently in class over a movie. The PTSD Foundation of America observes that 7.8% of Americans will experience PTSD at some point in their lives. But most people who experience PTSD are children under the age of 10 or war veterans. Furthermore, an NCBI publication reveals that intimate group support among fellow trauma victims (CISD) and rigorous pre-trauma training (CISM) are effective methods for helping the PTSD victim to move forward in her life.

There are some connections between media and PTSD, such as a study published last December which observed that some Americans who watched more than six hours of media coverage about the Boston Marathon bombings experienced more powerful stress reactions than those who refrained from watching the news or who were directly there. Another UC Irvine study found that 38% of Boston-area veterans who suffer from PTSD and other mental disorders experienced some emotional distress one week after the bombing. But these studies point to (a) people who already suffer from PTSD, (b) PTSD victims being exposed to media for a lengthy duration, and (c) PTSD victims in close proximity to a recent attack.

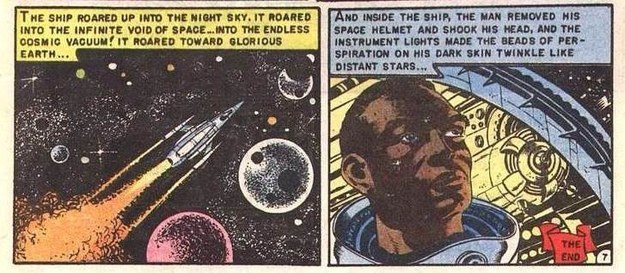

It is certainly reasonable for a professor to ask her class if any student suffers from PTSD, but the trigger warning approach is uncomfortably similar to the Comics Magazine Association of America’s crackdown on comic books over gory content in 1954, which led Charles F. Murphy to wrongfully conclude that reading violent comics leads to juvenile delinquency. As Saladin Ahmed recently pointed out at BuzzFeed, Murphy’s Puritanical Comics Code — a kind of self-regulated and equally self-righteous “trigger warning” system of the time — forced a black astronaut to be made white in order for Al Feldstein and Joe Orlando’s “Judgment Day” to run. (Before the Comics Code, the story would have appeared without a problem.) The pro-trigger warning crowd also refuses to consider the benefits of confronting trauma. If Steve Kandell hadn’t possessed the courage to visit the 9/11 Memorial Museum 13 years after his sister was killed in the attacks, then we would not have learned more about that tourist attraction’s crass spectacle and its deeply visceral effect on victims. There was no trigger warning at the head of his essay.

Discouraging students from confronting challenging topics because of “a negative emotional response” may also result in missed opportunities for humanism. In her thoughtful volume A Paradise Built in Hell, Rebecca Solnit examines numerous instances of people reacting to disasters. Contrary to the reports of doom and gloom presumed to follow a disaster, people more often react with joy and a desire to reforge social community. Those distanced from disaster tend to become more paralyzed with fright. No less a literary personage than Henry James, who read sensationalistic accounts of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, imagined that his brother William underwent some perdition: “I feel that I have collapsed, simply, with the tension of all these dismal days,” he wrote in a letter. “I should have told you that I have shared every pulse of your nightmare with you if I didn’t hold you quite capable of telling me that it hasn’t been a nightmare.” But William. who was impressed with the rapid manner in which San Francisco came together, replied, “We never reckoned on this extremity of anxiety on your part.”

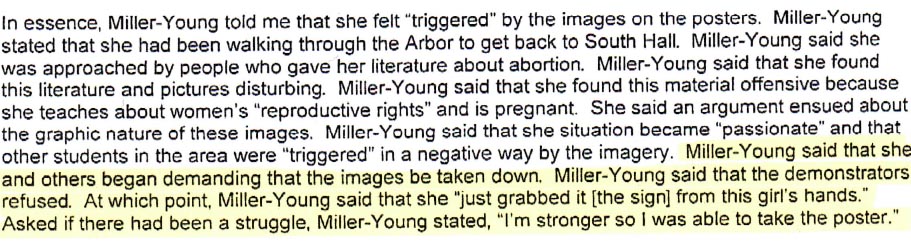

Only a week after Loverin’s resolution was passed, a group of anti-abortion activists had one of its banners, which featured a bloody picture of an aborted fetus, plucked by professor Mireille Miller-Young. A YouTube video capturing this incident features the professor pushing Joan Short, one of the Christian activists and the person operating the camera, after she attempts to retrieve her sign from an elevator. At the 2:46 mark, Miiller-Young can be seen kicking Short’s shoe out of the elevator bank.

The police report, which I obtained from the Santa Barbara Independent‘s Tyler Hayden (the PDF can be viewed here), cites “triggering” as one motivations for Miller-Young’s actions. Miller-Young asked the Christian activists to remove the sign. They refused. Miller-Young grabbed the sign and destroyed it in her “safe space” with scissors. “I’m stronger,” said Miller-Young, “so I was able to take the poster.”

As a hard progressive and free speech advocate who is strongly pro-choice and as someone who finds gory pictures of aborted fetuses to be a repugnant response to civility, I am nevertheless appalled that a supposedly enlightened figure of authority like Miller-Young would use “trigger warnings” as an excuse to not only shut down another person’s perspective, but to completely destroy the sign used to present it. These activists were not harassing young women outside of an abortion clinic, yet Miller-Young claims in the police report that “she felt that the activists did not have the right to be there.”

Many ostensible liberals have attempted to paint “trigger warnings” as something harmless, yet they refuse to see how appending a precautionary warning can lead to a chilling curb of free speech. And like Miller-Young, in their rush to condemn, it becomes clear that they are less interested in comforting those who are sensitive and more concerned with painting anyone who disagrees with them as either “a jerk” or someone who delights in the suffering from others. On Twitter, two privileged white male writers with high follower counts revealed their commitment to petty despotism when opining on the trigger warning issue:

If your argument against trigger warnings goes like "Do people allergic to cat hair need trigger warnings for CAT IN THE HAT" you're a jerk.

— Joe Hill (@joe_hill) May 20, 2014

Deeply opposed to "trigger warnings"? You might also be that dude who thinks it's jolly fun to set off firecrackers near people with PTSD.

— John Scalzi (@scalzi) May 20, 2014

We have seen recent literary debates about unlikable characters, an essential part of truthfully depicting an experience. But if an artist or a professor has to consider the way her audience feels at all times, how can she be expected to pursue the truths of being alive? How can a student understand World War I without feeling the then unprecedented horror of trench warfare and poison gas and burying bodies (a daily existence that caused some of the bravest soldiers to crack and get shot for cowardice if they displayed anything close to the PTSD that they felt every minute)? How can one understand rape’s full hurt and humiliation if one does not wish to become familiar with its baleful emotions? How can any student comprehend climate change if the default response is to ignore the news and play a distracting cat video that will amuse her for two minutes?

I realize that the trigger warning police mean well, but human beings are made of more resilience and intelligence than these unlived undergraduates understand. Hashtag activism may work in a virtual world of impulsive 140 character dispatches, but it cannot ever convey the imbricated complexities of the human spirit, which are too important to be stifled and diminished by a censorious menagerie of self-righteous kids, including middle-aged genre writers who can’t push their worldview past adolescent posturing that’s as preposterous as Jerry Falwell claiming emotional distress over a parody.