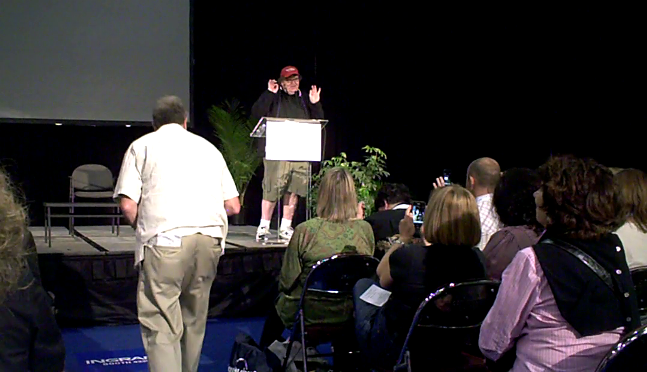

A somewhat trashed Michael Moore arrived ten minutes late for his Wednesday morning “signature event” (“a unique new opportunity here,” according to the man who introduced him, who also declared that Moore “forces us to react”) at BookExpo America. Moore, dressed in a red baseball cap and green cargo shorts, began his presentation by offering tepid yet crowd-pleasing quips about the Republicans cutting the Veterans Administration, eliminating traffic lights, and getting rid of kittens.

“Enough picking on them,” said Moore. “They’ve got a rough road ahead of them.” He then continued with a lot of football metaphors for the audience, which didn’t really look like sports enthusiasts. “I was saying last night, you know, they caught this great pass back in November and they started running in the opposite direction back on the football field away from their goal!”

It appeared that Moore didn’t quite understand the type of audience that comes to BEA.

“I assume most of you work in bookstores?” uptalked Moore. “The librarians are here?” When a handful of teachers responded to his Catskills act, he replied, “Some teachers? Oh great. Of course teachers are to blame for everything. All the money that they’re taking from us.”

Then having secured a low-key audience, Moore announced his new book, Here Comes Trouble: Stories From My Life, due out in September. The book, a collection of two dozen short stories (“but they’re all nonfiction”), chronicles Moore’s life before Roger & Me.

“There’s a short story about getting lost inside the Capitol building at eleven years old,” said Moore. “I didn’t see the sign that said SENATORS ONLY.” A man reading a newspaper — who turned out to be Robert Kennedy — helped Moore find his parents that day.

Another story involves Moore asking his parents if he could leave home at fourteen. “I said I wanted to be a priest. So I went to the seminary at fourteen years old.” Moore explained that the story allowed him to investigate his Catholicism.

“There’s a whole bunch of things like that,” said Moore. “I found myself present at a terrorist incident in the 1980s.” That incident allowed Moore to “write about what it’s like to actually be present at one of those terrorist incidents and live.”

The book, continued Moore with his masterful aw-shucks put on, “explains how I got to be where I got.” Yet he never explained how any of his stories, which also concern how he hired many ex-Navy SEALS for his security detail, would be of value to someone who was unemployed or trying to pay off a subprime loan. Moore reported that the stories were “interesting and wild. Some are funny and not so funny.”

Moore than read an excerpt from his book (and most of his presentation time was devoted to this). The excerpt recreated his infamous night at the 2003 Academy Awards. “It’s weird,” said Moore in the middle of reading. “It’s the first time I’ve read those words out loud since that night.”

Moore’s excerpt revealed that Moore was convinced that he had let everybody down. “I ruined their night and I suddenly sunk into a pit of despair,” read Moore. But there was more than a hint of self-aggrandizement in his excerpt. “People stepped away from me for fear that their picture would be taken.” This correspondent had to wonder if other people considered Moore to be as important as he clearly thought himself to be. Moore noted that film studio executive Sherry Lansing came up to him and said, “It hurts now. Someday you’ll be right. I’m so proud of you.” Moore’s excerpt revealed that he “believed they were right. I got to listen to more boos over the next 24 hours. Going through the hotel. Walking through the airport.”

But Moore’s excerpt was disingenuous. Because he failed to observe that when you say something outrageous and/or contrarian before a large crowd, they’re not exactly going to welcome you in open arms. When he returned home from the Oscars ceremony, he saw signs tacked up on his property.

“It was time to call in the Navy SEALS,” Moore read with typical subtlety. Moore explained that he had hired a security group composed of former SEALS, that he had been assaulted and people had tried to assault him, and that one person had tried to blow up his house. “The SEALS basically saved me and kept me alive.”

Kept Moore alive? Moore has certainly said and filmed many brave and provocative moments in his career. But I wasn’t quite sold on his pity act. Perhaps there’s an additional moment in his forthcoming book in which he comes to terms with the fact that he’s a loudmouth. But that pivotal introspection and unapologetic acceptance of his nature seemed to be missing.

This discrepancy proved especially troubling when Moore painted two of his enemies as obsequious types seeking an apology. One guy who called him a “shithead” allegedly recanted. “I told him that we had more in common than not. Eventually I got a smile from him.” Another man working the boom mike on The Tonight Show approached Moore shortly after his guest appearance. He had apparently yelled “Asshole” at the Oscars. According to Moore, this man had tears in his eyes and said, “I never thought I’d see you again. I can’t believe I’d get the chance to apologize to you.” “You did nothing wrong,” replied Moore. “You believed your President. You’re supposed to believe your President. If we can’t expect that as the minimum in office, then we’re doomed.”

To turn Moore’s logic around, if we can’t expect the filmmaker to consider that there may be problems with his approach and that not all of humanity will bow in sycophantic deference, then perhaps his book project is a doomed prospect for anybody who disagrees with his politics or his methods.

When he finished reading, there was a loud applause.

“That was really cool,” said Moore. “I got to do this for the first time.” Moore didn’t thank the crowd.