[This is the first in a series of dispatches relating to the New Directors/New Films series, running between March 23, 2011 and April 3, 2011 at MOMA and the Film Society of Lincoln Center.]

“The bank is something else than men. It happens that every man in a bank hates what the bank does, and yet the bank does it. The bank is something more than men, I tell you. It’s the monster. Men made it, but they can’t control it.” — The Grapes of Wrath

It’s easy for anyone with anything half-approaching a conscience to condemn the scummy vulpine gamblers who led us into the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. But Margin Call, which takes place during one very dark night in 2008, has a surprisingly nuanced portrait buried beneath its zesty dramatic intrigue. Yes, it takes a certain chutzpah to live a life (as one character does) where one claims want when the after-tax take of a $2 million annual salary is gobbled up by prostitutes and restaurants and cars and clothes. Yet the men and the women of Margin Call‘s unnamed firm (which bears striking similarities to Lehman Brothers) aren’t entirely without feeling. They’re just very good at compartmentalizing their emotions, which have been perfected after many years of greasing the wheels. That reality may very well be the true horror.

Our introduction to sales manager Sam Rogers (Kevin Spacey) is just after he’s received the news that his dog is sick. A few minutes later, he’s rallying the troops after a corporate bloodbath, saying, “80% of this floor was just sent home forever. But you were better.” He tells his salesmen that the downsized employees are “not to be thought of again.” How does he survive? One clue comes later in the film when Rogers is asked to take in some very bad news. He replies, “I don’t want to hear this. How do you think I’ve stuck around this place so long?”

But then it’s that failure to listen, that disinterest in what came before or what’s coming next, which is part of the problem. Eric Dale (Stanley Tucci) is one of the firm’s downsized casualties. He’s an analyst who we later learn helped design bridges that has saved thousands of commuter hours. And just as he’s working on some minatory projections showing serious volatility, the kind of financial Nagasaki with casualties exceeding the firm’s total value. But he isn’t even given the time to finish or explain his work. He’s escorted out of his office. And he’s informed by the icy HR people that he won’t have access to his computers again. He’s given a pamphlet (complete with the title LOOKING AHEAD and a preposterously sunny sailboat on the cover) that will provide “assistance with this transaction in your life.” And as he’s holding his banker’s box in the street, he discovers his cell phone is shut off. But just before heading from The Street to the streets, he does manage to get a flash drive with this data into the hands of the 28-year-old Peter Sullivan (Zachary Quinto), and that’s only because Peter has thought to accompany him to the elevator. Sullivan continues with Dale’s work and discovers the inevitable.

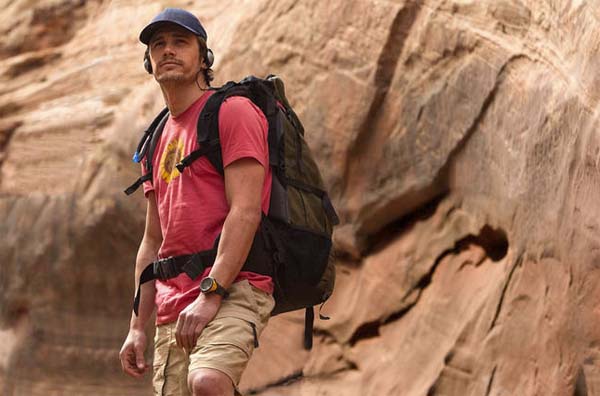

Sullivan is an analyst who, like many of his fellow employees, came to the firm for the money. He doesn’t seem as put out as his 23-year-old coworker, Seth Bregman (Penn Badgley), who can’t comprehend life without a job at the firm. (Bregman is later seen sobbing in the men’s room, an image that somehow feels worse than a stockbroker throwing himself out the window, because of the terror he must hide to show that he’s a team player.) But Sullivan does represent some missing link in the devolutionary masculine slide from ethical geek to thuggish lucre. Quinto here is terrific, playing the part with slight bites of the lower lip, rolled up shirtsleeves, and eyes that take in his increasing responsibilities with a reluctant professionalism that could, in the next decade or two, transform him into the ladder-climber wanting it all. Or maybe he’ll end up like Eric Dale: a risk management analyst let go for doing the right thing.

Margin Call features plentiful shots hinting at this blindsided mode of survival. One extraordinary moment occurs in an elevator as two executives argue over ratting each other out during the fallout, with a cleaning woman occupying the center of the frame, staring almost directly at the audience and seemingly not listening to this language. Another moment sees Sullivan and Bregman sitting in a gentleman’s club, the camera parked at a static shot quite far away, contemplating a stripper’s take home pay. Like many young men who are arrogant before their prime, they are so sure they know the numbers. And these fixed camera angles give us some sense of what they cannot see before them.

To some degree, Margin Call is working in the old school storytelling tradition that, in the wake of The Social Network, appears to be looking for a modest comeback. The film isn’t so much interested in the dry theoretical details, but it is concerned with the desperate emotions that force these people to scheme and capitulate. That ineluctable narrative decision may very well cause the picture to be declared by naive by its naysayers. But as someone who once silently observed the young and the hubristic (while also very young, which made the whole thing very odd) while working three months at Morgan Stanley, I can tell you that Margin Call is right on the money.

The graying Spacey – who is looking closer to his mentor Jack Lemmon as he gets older – forms something of a bridge between this film, Swimming with Sharks, and Glengarry Glen Ross. But his role is somewhat more understated. He’s been around the block so many times that he knows how to marshal his energy. And Spacey likewise cedes many of the scenes to Jeremy Irons, the firm’s head who shows up in a helicopter, asking the bright young analysts to explain the intricate data “as you would to a small child.” Margin Call‘s stress comes from the Nicorette chomping and rooftop smoking instead of the anxious indoor smoking, and overhead shots of New York replace Glengarry‘s cutaway shots of rattling Chicago subways.

The dialogue here isn’t just witty and wry. Care has also been taken to give Sam Rogers some grammatical gaffes. He describes “a very unique [sic] situation” when he’s asked to persuade his floor to perform the impossible and he often elides verbs such as “has” from his dialogue when speaking among the top executives. It’s almost as if Spacey came into the firm straight from high school. Or maybe he wants to appear stupid.

If the film has a liability, it may very well be Demi Moore playing the cold Sarah Robertson. Writer/director J.C. Chandor does make enlightened efforts to show that an anthracite heart isn’t limited to either of the two genders. (For example, the HR people at the beginning are all women and are all colder than the men they let go.) But the Moore character, aside from some predictable scheming, doesn’t really contribute much to the story.

Still, Margin Call is a very impressive debut from Chandor, who, if Hollywood gives him several films to flesh out his talents, may just be another Sidney Lumet in the making.