If the reviews are read, it is by those who seek a confirmation, either of their own gut reaction to a new sit-com or of a suspicion that you are a jerk. You can no more review TV according to agreed-upon criteria than you can review politics or sports or old girl friends — or compile a mobile history of the infinite. The lout on the next barstool also considers himself an expert; “Seen in this matter,” says Borges, “all our acts are just, bt they are also indifferent. There are no moral or intellectual merits.” Less attention was paid in March of 1972 to Senator John Pastore’s hearings on the impact of televised violence than was paid to spring-training baseball.

However, the consolations made up for the desperations. (A) You are being paid to watch television, which means that you don’t have to apologize what all your friends do secretly and feel guilty about. (B) It is something you can actually do with your children, instead of reading Babar aloud for the 157th time or running a staple through your thumb. And (C) being powerless is liberating. You can say what you want about the play and the actors; it won’t close, and they won’t be fired, on your account. Since television is about everything, you can review everything. Attention may not be paid, but hostilities will be projected, and you’ll be the healthier for the projecting of them, even if your society is not. As Borges put it, “We took out our heavy revolvers (all of a sudden there were revolvers in the dream) and joyfully killed the Gods.”

— John Leonard, This Pen for Hire (1973)

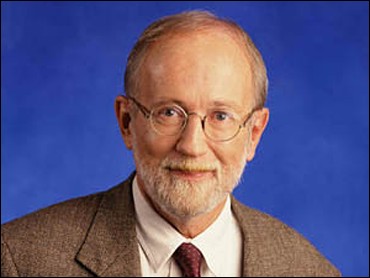

John Leonard is dead. He was 69. Aside from serving as editor of the New York Times Book Review (back when it actually meant something) during its glory years between 1971 and 1975, Leonard contributed a monthly books column for Harper’s and served as television critic for New York Magazine.

John Leonard is dead. He was 69. Aside from serving as editor of the New York Times Book Review (back when it actually meant something) during its glory years between 1971 and 1975, Leonard contributed a monthly books column for Harper’s and served as television critic for New York Magazine.

Leonard was one of the last old-school greats, and one of the people I looked to in developing my own critical voice. (When I was commissioned to write a books column for the decommissioned 02138, John Leonard was one of my key models.) He wrote honestly and passionately about literature, was not afraid to take prisoners, was inclusive of genre and translated titles. When I plunged into his pre-NYTBR work for the first time some years ago (namely through the above-referenced quote), I was stunned to see how wonderfully feral and sensible he was. I’m convinced that if Leonard had started writing a decade ago, he probably would have been a litblogger. In the last two decades, Leonard had calmed down a bit, refraining from some of his take-no-prisoners pieces. As he explained at a BEA panel a few years ago, if he didn’t like a book, he wouldn’t write about it. He wanted to continue the conversation.

I had the good fortune of meeting Leonard just before this panel. Only an hour before, my bald pate had collided with a STOP sign, prompting considerable blood and a trip to Duane Reade. With a gargantuan bandage on my head, I looked something like an escaped mental patient. Leonard didn’t bat an eye. I thanked him for his years at the NYTBR, which I had read on microfilm as an undergrad. Leonard then told me that he read my site daily, and liked the work I was doing. When I asked him if he saw any comparisons between the ongoing print-digital debate and his early career as a journalist, he beamed up, “Oh yeah! This is nothing new. They said the same thing about the alt-weeklies, and look where they are today.” In an interview with Meghan O’Rourke, Leonard said, “Reviewing has all become performance art; it’s all become posturing. It’s going to have to be the lit blogs that save us. At least they have passion.”

It’s difficult to imagine a literary world without John Leonard. He was the rarest of critics: a sharp, populist-minded essayist with an open mind writing beautifully without fear.

More Tributes: Scott McLemee, Sarah Weinman, Emily Gordon, Hillary Frey, Jason Boog, and Mark Lotto.

See Also: Studs Terkel on John Leonard, Leonard archive at New York, Leonard archive at New York Review of Books, Leonard archive at The Nation, Leonard’s introduction to Paradise Lost, Leonard’s early championing of Toni Morrison, Leonard on Lethem, and Bill Moyers interview.

Also: A must-read autobiographical account of Leonard fighting for journalistic ethics as editor of the New York Times Book Review.