(This is the sixteenth entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: This Boy’s Life.)

She remains a bold and inspiring figure, a galvanizing tonic shimmering into the empty glass of a bleak political clime. She was bright and uncompromising and had piercingly beautiful eyes. She was a stratospheric human spire who stood tall and tough and resolute above a patriarchal sargasso. Three decades after her death, she really should be better known. Her name is Beryl Markham and this extraordinary woman has occupied my time and attentions for many months. She has even haunted my dreams. Forget merely persisting, which implies a life where one settles for the weaker hand. Beryl Markham existed, plowing through nearly every challenge presented to her with an exquisite equipoise as coolly resilient as the Black Lives Matter activist fearlessly approaching thuggish cops in a fluttering dress. I have now read her memoir West with the Night three times. There is a pretty good chance I will pore through its poetic commitment to fate and feats again before the year is up. If you are seeking ways to be braver, West with the Night is your guidebook.

She grew up in Kenya, became an expert horse trainer, and befriended the hunters of her adopted nation, where she smoothly communed with dangerous animals. For Markham, the wilderness was something to be welcomed rather than dreaded. Her natural panorama provided “silences that can speak” that were pregnant with natural wonder even while being sliced up by the cutting whirl of a propeller blade. But Markham believed in being present well before mindfulness became a widely adopted panacea. She cultivated a resilient and uncanny prescience as her instinct galvanized her to live with beasts and brethren of all types. It was a presence mastered through constant motion. “Never turn your back and never believe that an hour you remember is a better hour because it is dead,” wrote Markham when considering how to leave a place where one has lived and loved. This sentiment may no longer be possible in an era where one’s every word and move is monitored, exhumed by the easily outraged and the unadventurous for even the faintest malfeasance, but it is still worth holding close to one’s heart.

In her adult life, Markham carried on many scandalous affairs with prominent men (including Denys Finch Hatton, who Markham wooed away from Karen Blixen, the Danish author best known for Out of Africa (to be chronicled in MLNF #58)) and fell almost by accident into a life commanding planes, often scouting landscapes from above for safari hunts. Yet Markham saw the butcherous brio for game as an act of impudence, even as she viewed elephant hunting as no “more brutal than ninety per cent of all other human activities.” This may seem a pessimistic observation, although Markham’s memoir doesn’t feel sour because it always considers the world holistically. At one point, Markham writes, “Nothing is more common than birth: a million creatures are born in the time it takes to turn this page, and another million die.” And this grander vantage point, which would certainly be arrived at by someone who viewed the earth so frequently from the sky, somehow renders Markham’s more brusque views as pragmatic. She preferred the company of men to women, perhaps because her own mother abandoned her at a very young age. Yet I suspect that this fierce lifelong grudge was likely aligned with Markham’s drive to succeed with a carefully honed and almost effortlessly superhuman strength.

Markham endured pain and fear and discomfort without complaint, even when she was attacked by a lion, and somehow remained casual about her vivacious life, even after she became the first person to fly solo without a radio in a buckling plane across the Atlantic from east to west, where she soldiered on through brutal winds and reputational jeers from those who believed she could not make the journey. But she did. Because her habitually adventurous temperament, which always recognized the importance of pushing forward with your gut, would not stop her. And if all this were not enough, Markham wrote a masterpiece so powerful that even the macho egotist Ernest Hemingway was forced to prostrate himself to editor Maxwell Perkins in a letter: “She has written so well, and marvelously well, that I was completely ashamed of myself as a writer.” (Alas, this did not stop Hemingway from undermining her in the same paragraph as “a high-grade bitch” and “very unpleasant” with his typically sexist belittlement, a passage conveniently elided from most citations. Still, there’s something immensely satisfying in knowing that the bloated and overly imitated impostor, who plundered Martha Gellhorn’s column inches in Collier’s because he couldn’t handle his own wife being a far superior journalist, could get knocked off his peg by a woman who simply lived.)

In considering the human relationship to animals, Markham writes, “You cannot discredit truth merely because legend has grown out of it.” She details the beauty of elephants going out of their way to hide their dead, dragging corpses well outside the gaze of ape-descended midgets and other predators. And there is something about Markham’s majestic perspective that causes one to reject popular legends, creating alternative stories about the earth that are rooted in the more reliable soil of intuitive and compassionate experience. For Markham, imagination arrived through adventure rather than dreams. She declares that she “seldom dreamed a dream worth dreaming again, or at least none worth recording,” yet the fatigue of flying does cause her to perceive a rock as “a crumpled plane or a mass of twisted metal.”

Yet this considerable literary accomplishment (to say nothing of Markham’s significant aviation achievements) has been sullied by allegations of plagiarism. It was a scandal that caused even The Rumpus‘s Megan Mayhew Bergman to lose faith in Markham’s bravery. Raoul Schumacher, Markham’s third husband, was an alcoholic and a largely mediocre ghost writer who, much like Derek Stanford to Muriel Spark, could not seem to countenance that his life and work would never measure up to the woman he was with. Fragile male ego is a most curious phenomenon that one often finds when plunging into the lives of great women: not only are these women attracted to dissolute losers who usually fail to produce any noteworthy work of their own, but these men attempt to make up for their failings by installing or inventing themselves as collaborators, later claiming to be the indispensable muse or the true author all along, which is advantageously announced only after a great woman has secured her success. Biographers and critics who write about these incidents years later often accept the male stories (one rarely encounters this in reverse), even when the details contain the distinct whiff of a football field mired in bullshit.

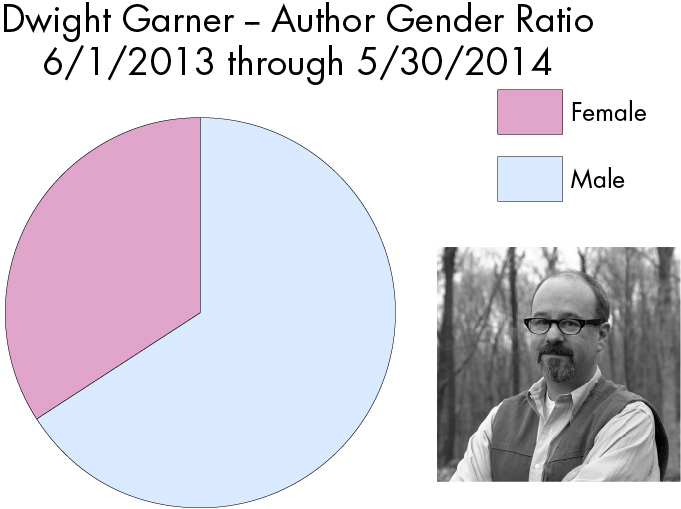

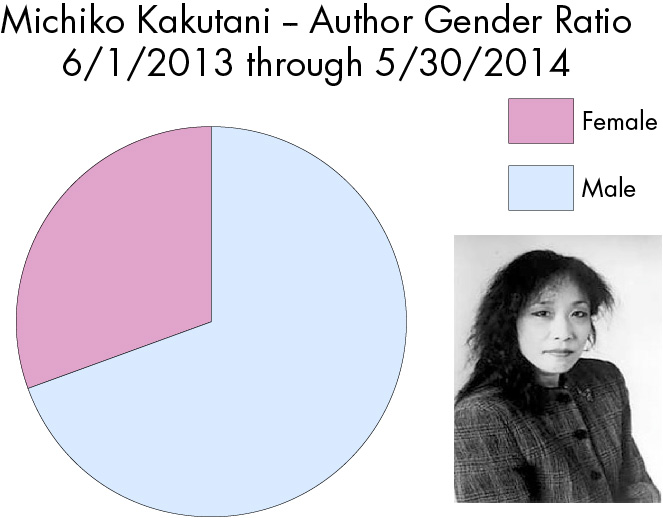

I was not satisfied with the superficial acceptance of these rumors by Wikipedia, Robert O’Brien, and Michiko Kakutani. So I took it upon myself to read two Markham biographies (Mary S. Lovell’s Straight on Till Morning and Errol Trzebinski’s The Lives of Beryl Markham), where I hoped that the sourcing would offer a more reliable explanation.

I discovered that Trzebinski was largely conjectural, distressingly close to the infamous Kitty Kelley with her scabrous insinuations (accusations of illiteracy, suggestions that Markham could not pronounce words), and that Lovell was by far the more doggedly reliable and diligent source. Trzebinski also waited until many of the players were dead before publishing her biography, which is rather convenient timing, given that she relies heavily on conversations she had with them for sources.

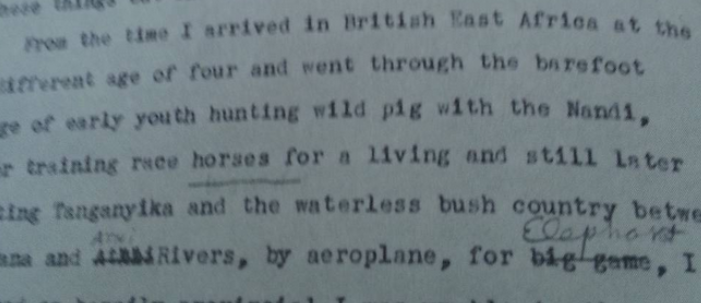

The problem with Schumacher’s claim is that one can’t easily resolve the issue by going to a handwritten manuscript. West with the Night‘s manuscript was typed, dictated to Schumacher by Markham (see the above photo). The only photograph I have found (from the Lovell biography) shows Markham offering clear handwritten edits. So there is little physical evidence to suggest that Schumacher was the secret pilot. We have only his word for it and that of the friends he told, who include Scott O’Dell. Trzebinski, who is the main promulgator of these rumors, is slipshod with her sources, relying only upon a nebulous “Fox/Markham/Schumacher data” cluster (with references to “int. the late Scott O’Dell/James Fox, New York, April 1987” and “15/5/87” — presumably the same material drawn upon for James Fox’s “The Beryl Markham Mystery,” which appeared in the March 1987 issue of Vanity Fair, as well as a Scott O’Dell letter that was also published in the magazine) that fails to cite anything specific and relies on hearsay. When one factors in an incredulous story that Trzebinski spread about her own son’s death that the capable detectives at Scotland Yard were unable to corroborate, along with Trzebinski’s insistence on camera in the 1986 documentary World Without Walls that only a woman could have written West with the Night, one gets the sense that Trzebinski is the more unreliable and gossipy biographer. And Lovell offers definitive evidence which cast aspersions on Tzrebinski’s notion that Markham was something of a starry-eyed cipher:

But this proof of editing by Raoul, which some see as evidence that Beryl might not have been the sole author of the book, surely proved only that he acted as editor. Indeed his editing may have been responsible for the minor errors such as the title arap appearing as Arab. Together with the Americanization of Beryl’s Anglicized spelling, such changes could well have been standard editorial conversions (by either Raoul or Lee Barker – Houghton Mifflin’s commissioning editor) for a work aimed primarily at an American readership.

The incorrect spelling of Swahili words has an obvious explanation. In all cases they were written as Beryl pronounced them. She had learned the language as a child from her African friends but had probably never given much thought to the spelling. Neither Raoul nor anyone at Houghton Mifflin would have known either way.

In his letter to Vanity Fair, and in two subsequent telephone conversations with me, Scott O’Dell claimed that after he introduced Beryl and Raoul “they disappeared and surfaced four months later,” when Raoul told him that Beryl had written a memoir and asked what they should do with it. This is at odds with the surviving correspondence and other archived material which proves that the book was in production from early 1941 to January 1942, and that almost from the start Beryl was in contact with Lee Barker of Houghton Mifflin.

When Raoul told his friend that it was he who had written the book, could the explanation not be that he was embittered by his own inability to write without Beryl’s inspiration? That he exaggerated his editorial assistance into authorship to cover his own lack of words as a writer?

From the series of letters between Beryl and Houghton Mifflin, it is clear that Beryl had sent regular batches of work to the publishers before Raoul came into the picture. As explained earlier, Dr. Warren Austin lived in the Bahamas from 1942 to 1944, was physician to HRH the Duke of Windsor and became friends with Major Gray Phillips. Subsequently Dr. Austin lived for a while with Beryl and Raoul whilst he was looking for a house in Santa Barbara. The two often discussed their mutual connections in Raoul’s presence. Dr. Austin is certain that Raoul had never visited the Bahamas, reasoning that it would certainly have been mentioned during these conversations if he had. This speaks for itself. If Raoul was not even present when such a significant quantity of work was produced, then that part – at the very least – must have been written by Beryl.

Lovell’s supportive claims have not gone without challenge. James Fox claimed in The Spectator that he had seen “photostated documents, from the trunk since apparently removed as ‘souvenirs’ and thus not available to Lovell, which show that Schumacher took part in the earliest planning of the contents and the draft outline for the publisher and show whole passages written by Schumacher in handwriting.” But even he is forced to walk the ball back and claim that this “proves nothing in terms of authorship.” Since Fox is so fixated on “seeing” evidence rather than producing it, he may as well declare that he visited Alaska and could see Russia from his AirBnB or that he once observed giant six-legged wombats flying from the deliquescent soup he had for supper. If this is the “Fox/Markham/Schumacher data” that Trzebinski relied upon, then the plagiarism charge is poor scholarship and poor journalism indeed.

So I think it’s safe for us to accept Markham’s authorship unless something provable and concrete appears and still justifiably admire a woman who caused Hemingway to stop in his tracks, a woman who outmatched him in insight and words, a woman – who like many incredible women – was belittled by a sloppy, gossip-peddling, and opportunistic biographer looking to make name for herself (and the puff piece hack who enabled her) rather than providing us with the genuine and deserved insight on a truly remarkable figure of the 20th century.

Next Up: Neil Sheehan’s A Bright Shining Lie!