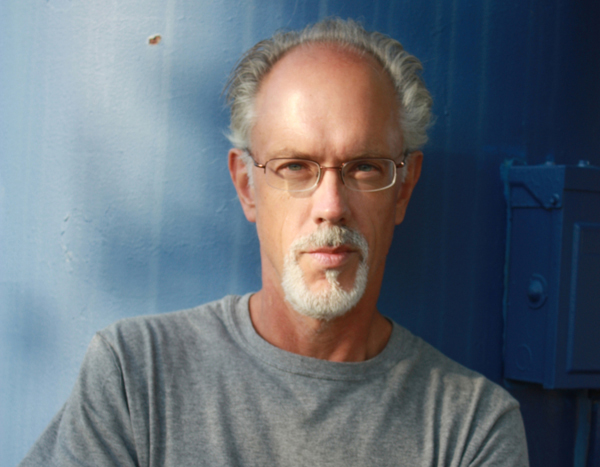

Mark Slouka is most recently the author of Brewster.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Author: Mark Slouka

Subjects Discussed: Gandhi’s pacifist maxims, Wilifred Owen, World War I poets, Vietnam, violence in fiction, Brewster in relation to Woodstock, people who still listened to Perry Como in 1968, memory and sex, listening as research, auctorial instinct, the poetry of real world vernacular, having a father as a storyteller, why Slouka’s characters are often defined by outside towns, viewing a life in relation to the next place you’ll settle, Slouka’s Czech background, Nazi memorabilia, Slouka’s reluctance in exploring the grounded, being a child of Czech refugees, lives lived on a borderline, geographically fraught characters, the bright bulb of heritage, broken lamps, crossing America 22 times, the wandering instinct, stories to tell at a bar, the Motel 6 as a gathering spot, developing a photograph of America through travel, Bob Dylan’s “Stuck Inside of Mobil with the Memphis Blues Again,” towns that people pass through on the way to somewhere nicer, the benefits of sharp elbows, why small towns get a bad rap in American literature, the influence of Sherwood Anderson, Richard Russo, metropolitan types who condescend to small towns, David Lynch, avoiding dark cartoonish material to write truthfully about bigotry, courting complexity, the terror of familiarity, when you know another person’s parents more than your own, finding approval in another family, mothers who mourn the sons that they lose, the revelations of characters who touch surfaces, being a “physical writer,” the physical as a door to memory, sudden transitions from violence to casual conversation, being a victim of belief culture, when the real enters the domain of fiction, knowing ourselves through the telling of stories, Slouka affixing misspellings of his name to the refrigerator, fridge magnet poetry, how Brewster deals with race, desegregation busing, racism and locked doors, Obama’s Trayvon Martin speech, the myth of other worlds, the 168th Street Armory, lingering racism in Brewster, “Quitting the Paint Factory,” how Slouka’s notion of leisure have adjusted in 2013, leisure vs. consumer capitalism, why humans are being colonized by machines, assaults on the inner life, Twitter and the Arab Spring, attention deficit, why the human population has turned into addicts, acceptable forms of leisure, the inevitability of multitasking, Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History, why four hour podcasts exist in a medium that eats away our time, being shaped in ways you don’t understand, Slouka’s declaration of war against the perpetually busy, the conditions that determine whether someone’s soul has been eaten, the church of work, why people work like dogs to consume more, being derided for sleeping eight hours a night, and Slouka’s elevator pitch for Brewster.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: The book oscillates between one of Gandhi’s most famous maxims (“First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win”) and references to war, whether it be Vietnam or the World War I poet Wilfred Owen. And I’m wondering, just to get started here, how did this backdrop of war and peace help you to zero in on these characters and this landscape? Was this your way of tipping your hat to a socially charged time without hitting the obvious touchstones?

Slouka: Yeah, I think so. It’s a matter of “all politics are personal” and vice versa. I was interested in writing about war. Because war’s in the background, of course. It takes place in the late 1960s. And the drums of Vietnam were going through the whole thing. But what I’m really writing about is the lives of these two young guys — seventeen or eighteen years old — who are fighting a very different private war: each in their own way, each with their own family, each with their own life. So the interplay — the back-and-forth between War writ large and war, lowercase, is something that interested me.

Correspondent: This is a very violent book. There’s a lot of smacking, slapping, and, of course, the revelation near the end. I mean, it’s pretty brutal. It’s almost as violent as being in any kind of battlefield. And I’m wondering if the larger social canvas of Vietnam almost forced your hand, when thinking about these characters, to really consider this domestic abuse and all of this terrible pugilism that’s going on underneath the surface.

Slouka: I think so. I think it’s probably unavoidable. I mean, I also grew up with guys like — let’s say Ray Cappicciano, the Ray Cap character who’s fighting a very real war at home. His dad is an ex-cop, a prison guard. He’s not a good guy. But one of my favorite scenes is actually in the book. It’s a scene in the cafeteria where Jon, the narrator, is reading Wilfred Owen’s poem about the trenches in World War I and the experience of watching someone die in a gas attack. And Ray Cap, who’s sitting across the table, basically goads him into reading it out loud. “I’m not going to read the poem.” “Read the poem.” He eventually reads the poem and Ray responds to it in a way that’s completely unexpected, even for him. And he responds to it probably because he understands on some deep visceral level what it’s like to be in battle. What it’s like to be drawn to battle and not be able to get away from it. I mean, Owen was wounded. He recovered. And then he reenlisted and then eventually died in the war. And Ray Cap is haunted by that. Because it’s like, “He went back?” He went back to this thing and eventually killed him? That’s his biggest fear. Because he keeps going back to the house where he has a hard life.

Correspondent: Yeah. Well, it’s something that foreshadows his particular existence. He needs to have almost a poetic guide to understand the predicament that he’s in.

Slouka: That’s right.

Correspondent: And he just can’t understand why Owen would go back to serve after he’s written this poem.

Slouka: Exactly.

Correspondent: I wanted to ask about how you depict this late 1960s in Brewster as a different place from Woodstock across the river. A place where people really don’t matter. I mean, they’re expected to fall into line. What kind of research did you do into Brewster of the late 1960s to develop this sense of what life is like? Where you can be an individual all you want, but if you don’t fall into line, you’re going to have trouble living here.

Slouka: Oh yeah. Well, research for a writer often entails just talking with people, listening to people. There’s this gorgeous New York area vernacular that I just fell in love with while writing this book. That Italian American/Irish thing that I never wrote about. I grew up listening to it and I never wrote about it. So this book was a homecoming for me. The research I did was just sort of sticking my nose out the door and listening to how people spoke. But I also had to remember a lot. And the truth is that the ’60s didn’t happen in the same way at the same time for all people. You know, one of the guys that plays a role in this book is an Irish Catholic kid named Frank who’s still listening to Perry Como in 1968 because he is. Because some people were. Brewster in 1968 was still in 1957 in a lot of ways. And it was happening. Watts was happening. Woodstock was across the river. But the day that Woodstock happens, my heroes end up going down to Yonkers. Because they don’t want to sit around listening to everything that they’re missing across the river and also because they’re poor. They’re working class kids. And a lot of working class kids didn’t make it to Brewster. Because they didn’t know that they opened the fences and it was twenty-three movie tickets to get into Woodstock. So they couldn’t go. So they’re fighting against a conservative, repressive, frightened culture that’s all around them. You know, some guy was hitching up his office pants saying, “Yeah, I got a dream. You know, I’ll pay the goddam mortgage.”

Correspondent: But it is interesting that Jon, in telling this tale, doesn’t really hit those touchstones. He says, well, “We were more aware of the Tet Offensive than a girl’s nipples.”

Slouka: (laughs)

Correspondent: But he doesn’t really announce what they talked about. In fact, there’s one point in the Tina episode where he has a perfect memory of what he talks about with the hippies. But then, when they leave, he can’t remember a single subject of what he’s talking about with Tina. And I find that really interesting. It’s almost like, despite the fact that he was well-steeped in the subject, he can’t remember that. It’s almost as if that doesn’t matter, you know?

Slouka: Well, that’s part of it. But he’s also having sex. (laughs)

Correspondent: Well, of course! That does have a way of…

Slouka: …erase the memory for a little while. But yeah, you remember certain things. You don’t for others. I mean, I personally think that the ’60s didn’t really become the ’60s until 1980. You know what I mean? Then when look back and we say, “Well, that was the ’60s.” But when you were in it, you didn’t think things were happening. Personally, I think the ’60s were in some ways, despite all the bullshit around the edges (and they’ve been reduced to a fashion statement), the fact is that they were probably the last time that we really considered altering on a mass scale what our priorities are in this country and how we would proceed. It didn’t work. It didn’t happen. But some things happened. It was an exciting time. So these guys knew that things were happening. They could hear it happening. But it wasn’t happening in Brewster. And that’s part of the tension in the book.

Correspondent: Going back to what you were saying earlier about how you made Brewster come alive. You say that you stuck your nose out the door. But you’re also competing with memory. And you’re dealing with who is still alive, who lived through that time, versus what you remember. I mean, at what point do you have to throw that aside and just rely on your own instinct and imagination for what you feel Brewster is or should be? I mean, how do you wrestle with all this?

Slouka: I think you have to throw it out very early. You just have to go by instinct. You just walk in. You know, you create a place that feels right on the page. That feels like a place that you can inhabit as a writer and believe in as a writer. And if you get that right, then eerily enough I think you get close to something that’s actually believable for other people. And it’s a kind of counterintuitive sort of thing. You’re following your own instinct. Because why would someone else understand that? And sometimes they don’t. But in my experience, if you trust yourself, you know, you make mistakes. You try to correct them and so on. But by the time you’re done, if you’ve trusted yourself and if you followed those instincts, then there’s a really good chance that other people will sense that there’s a sort of organic quality to that imaginative thing that you brought and they’ll buy into it hopefully.

Correspondent: I’m curious about this. I mean, how many people did you talk with? And if you’re hearing another perspective of that particular time, how does this mesh with you trusting yourself as a writer? You trusting that truth, that perspective, that world that you are planting and growing in the book?

Slouka: For me, when I talk about listening to people, it’s not about listening to their stories necessarily, though people will tell you their stories and I love to hear them. It’s about listening to how they talk. It’s about listening to — you know, I love the way people talk there. I was getting some beer at the A&P recently and I asked this kid. I said, “Where’s the beer at?” And he said, “Well, okay, you go to the back and you look right.” And I was walking away. I said thanks. I’m walking away. And he said, “It’s the only thing I know where it is in the store.” Well, if you write that down on paper — “It’s the only thing I know where it is in the store” — it’s a mess. The sentence is a disaster. But it’s beautiful too. There’s a kind of poetry to it. And that can be expanded infinitely. So for me, it was a matter of imagining this place. I had certain bones I needed to pick with my own past, with the memories of people that I knew back then. You’re trying to resolve certain things that aren’t completely clear to you even as you’re writing them, except that you know that you have to write them. But the research involves just opening your ears, which I did for the first time in this. I never wrote an American book before. This is my first truly American book. It was just a question of giving myself permission to set a particular — to say, “Look, you were born and raised in this country. You’ve listened to these people for fifty years. Just shut up and write.” And I’ve tried to do that and hopefully it worked out.

Correspondent: It seems to me — I’m just going to infer here. Maybe you can clear this up. If you had a bone to pick with yourself, maybe some of these interesting sentences that you hear at the A&P or that you hear from people telling you about the period, maybe it’s a way to get outside of yourself or to plant what might almost be called a more objective voice. Because you have something more concrete to work with. Is that safe to say?

Slouka: I think that makes perfect sense. I think that’s exactly what it was really. And this book is a homecoming. I lost my father the day after this book was finished. Literally. And he was the storyteller in my life. We had our hard times. You know, he drank when I was a kid. The last fifteen years were great. But I spent most of my writing life writing stories that were set elsewhere. They were from my parents’ time. They were the Resistance in Prague during the Second World War. It was ancient Siam. The Siamese Twins. Da da da. You know, it’s time to write my own story. Not that those weren’t, but this one’s my own in a different way. I think there’s something about listening, about coming home to Brewster, which is a difficult place to explain though I’m fond of it…

Correspondent: Well, let’s talk about this. Because in The Visible World, your narrator is a child of Czech refugees from World War II. Not unlike yourself. In Brewster, Jon’s family is Jewish. They have escaped from Germany. You have Frank, who we just talked about earlier. He comes from Poland. You have Karen even, from Hartford on a more limited scale. You have Ray talking with the women behind the cafeteria. So there is very much a quality to your fictitious characters in which they always come from somewhere else. Or they’re not defined by the place they live right now. And I was wondering why that’s your affinity.

Slouka: Where that comes from.

Correspondent: Not necessarily where that comes from, but do you feel that it’s truer to write about someone or that you’re going to get a more dimensional character if they have some kind of additional background? That no one is really from anywhere?

Slouka: Oh god, you’re good at this. The problem is that it’s me. I’m the one who’s not really from one place or another. You know what I mean? I grew up on the fault line between two cultures. Two languages. Two histories. I grew up in a Czech ghetto in Queens, New York, for Christ’s sake, right? My first language was Czech. I didn’t speak English until I was five and I went out on the playground and had to figure out what the hell was going on and why these kids weren’t speaking Czech. My problem — and that’s just my life — is that with the possible exception of a little cabin that we have in a place called Lost Lake, I’ve never really had a home. And whenever I was in one place, I was always looking for the next good place. The next place and the next place. That’s one of the problems for me in getting older. You’re running out of time to look for the next place and the next place and the next place. I think I’ve transferred a lot of that kind of restlessness, which I think is very American actually. Americans are always looking for the next great place. I’ve transferred that restlessness into my characters, who are usually from everywhere but here. I mean, it’s possible that actually Brewster is the most grounded of my books. Because these kids are from there. Though it’s also kind of ironic that they’re also the most trapped. I mean, they’re from Brewster and they want to get the hell out. Again, not unlike me. It’s like: I’m here. How soon can I leave?

Photo: Maya Slouka

(Loops for this program provided by Nightingale, KBRPROD, ferryterry, 40A, DeepKode, and ProducerH.)

The Bat Segundo Show #509: Mark Slouka (Download MP3)