(This is the fifteenth entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: A Mathematician’s Apology.)

It is worth recalling that the Boy Scout, that putative paragon of American boyhood virtue, originated in 1909 with a man lost in the foggy haze of a mazy London byway. W.D. Boyce was a recently divorced newspaperman cast adrift in the English mist, until he was guided by a uniformed lad known only as the Unknown Scout. This young whippersnapper, who was no soldier and had no tomb (unless you count a mangy Silver Buffalo memorial that presently stands in Gilwell Park), steered Boyce to his destination and refused Boyce’s tip after that gent hoped to consummate his gratitude. The boy did so not because he was a well-paid German stevedore or a terrified Uber driver hoping to hold onto his job, but because he was merely doing his duty and this was enough recompense, thank you very much. From here, Boyce asked the boy about his coterie, was allegedly led to Boy Scouts HQ like a starry-eyed drifter seeking a new easy access religion, and encountered Chief Scout Robert Baden-Powell, an irrepressible do-gooder who intoxicated Boyce with tales of uniforms and valor and decency and truth and justice and many other nouns etched with ostentatious pedigree and scant subtlety that were later memorialized in a handbook published in six fortnightly parts called Scouting for Boys. Four months later, Boyce returned to the States to found the Boy Scouts of America. He had found his calling. Shortly after this, presumably emboldened by the new youthful virtues flooding through his veins, Boyce would marry a well-connected woman twenty-three years younger. But Boyce’s brio was not enough to preserve this second marriage, which dissolved within two years. The Boy Scouts, on the other hand, have continued to endure, albeit with plentiful dissimulation saddled to the “Be prepared” credo.

It is worth recalling that the Boy Scout, that putative paragon of American boyhood virtue, originated in 1909 with a man lost in the foggy haze of a mazy London byway. W.D. Boyce was a recently divorced newspaperman cast adrift in the English mist, until he was guided by a uniformed lad known only as the Unknown Scout. This young whippersnapper, who was no soldier and had no tomb (unless you count a mangy Silver Buffalo memorial that presently stands in Gilwell Park), steered Boyce to his destination and refused Boyce’s tip after that gent hoped to consummate his gratitude. The boy did so not because he was a well-paid German stevedore or a terrified Uber driver hoping to hold onto his job, but because he was merely doing his duty and this was enough recompense, thank you very much. From here, Boyce asked the boy about his coterie, was allegedly led to Boy Scouts HQ like a starry-eyed drifter seeking a new easy access religion, and encountered Chief Scout Robert Baden-Powell, an irrepressible do-gooder who intoxicated Boyce with tales of uniforms and valor and decency and truth and justice and many other nouns etched with ostentatious pedigree and scant subtlety that were later memorialized in a handbook published in six fortnightly parts called Scouting for Boys. Four months later, Boyce returned to the States to found the Boy Scouts of America. He had found his calling. Shortly after this, presumably emboldened by the new youthful virtues flooding through his veins, Boyce would marry a well-connected woman twenty-three years younger. But Boyce’s brio was not enough to preserve this second marriage, which dissolved within two years. The Boy Scouts, on the other hand, have continued to endure, albeit with plentiful dissimulation saddled to the “Be prepared” credo.

This legend, which isn’t nearly as imaginative or as thrilling as Robert Johnson signing away his soul to the devil in exchange for spangling guitar chops, has nevertheless become as accepted and as apocryphal as the birth of the blues or any story of rugged outliers founding tech startups in their garages or, for that matter, the cloying cherry tree myth associated with George Washington, a shrewd political operator who claimed that he could not tell a lie despite deceiving many over a lifetime about his professed lack of political expertise. Boy Scout booster (and sex therapist!) Edward Rowan has pointed out that Boyce outed himself in a February 27, 1928 letter, claiming that he was not floating in the Dickensian murk, but merely standing before the Savoy Hotel while contemplating the question of whether he should cross a street. Moreover, others have suggested that there was no fog during that evening. As one excavates further into W.D. Boyce’s history, one learns that this sanctimonious founder was a racist, even denying African-Americans entry into the hallowed organization. (Boyce also published a journal called The White Boy’s Magazine.) By the late 1980s, the Boy Scouts were forced to establish protective measures in response to countless sex abuse cases later documented by reporter Patrick Boyle in 1991. The Boy Scouts of America, a seemingly sacred institution, had been little more than a seductive shawl disguising the ugly American id. It is thus the perfect metaphor for Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life, a moving memoir about a boy wrestling with the lies, the duplicities, and the hypocrisies of growing up in America. It is an especially cogent volume in an epoch of fake news, covfefe, and thundering Republican men casually asphyxiating the weak and the vulnerable in the name of old school virtue.

For young Tobias (aka Jack, a sobriquet inspired by an altogether different London), the deceptive pose was a way of being and coping through a rough-and-tumble existence. This Boy’s Life opens with Toby and his mother retreating from an abusive man in Florida by way of a dodgy Nash Rambler with an overboiling engine. Their hope was to find fortune through a desperate uranium hunt by way of a poor man’s Geiger counter. Like many Americans before, the westward journey here is one of escape and, as one pores through the memoir’s crisply paced pages, increasingly about assuming roles that bear no resemblance to reality. The cooing pop songs crooning from the radio provide voices for Toby to emulate, perhaps serving as a staging area for transformation. Yet Catholicism, itself a practice just as fraught with frangible self-abengation as the Boy Scouts, also represents the new terrain from which to launch an identity. Toby’s father, telephoning from Connecticut, claims that the family line has always been Protestant or Episcopalian, but Wolff informs us that he learned of his true Jewish heritage ten years after this revelation. Names, identities, veneers, and backgrounds are the melting pot from which to sprout a respectable soul, yet Toby scoffs at the purported innocence of this problematic chrysalis. “Power,” writes Wolff, placing his budding irritation within the context of his later experience in Vietnam, “can only be enjoyed when it is recognized and feared. Fearlessness in those without power is maddening to those who have it.”

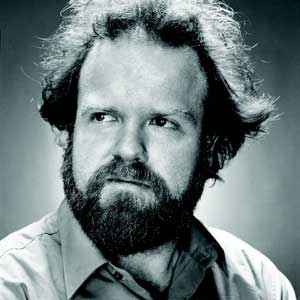

Woolf’s Vietnam memoir, In Pharaoh’s Army, would chronicle similar tensions between patriotic duty and survival, and one must observe that the two memoirs are united by Wolff possessing a gun, that priapic symbol of American manhood that has caused so much recent and needless terror. This Boy’s Life sees these uncertain seeds planted in loam long before basic training. I once had the good fortune to interview Wolff in 2008 and he revealed that he was dead set against narcissism’s pathology overtaking any story. Which leads me to believe that Wolff understands, as William Gass has observed in a notable essay on narcissism and writing, that autobiographers turn themselves into monsters, often hiding deceit behind their confessions. To reckon poignantly with a life, a memoirist must never cover up his shame or settle scores with self-serving vigor, for he invites a dishonesty in which the professed act of soul-bearing smudges the more important ink needed for corrupted but authentic memory.

What is most striking about This Boy’s Life is that Wolff never sugarcoats his life. Nor does he beckon the reader to feel sympathy for him, even as he succumbs to abuse from Dwight, the abominable man whom his mother Rosemary eventually tries to forge a family with. It is the shakiest of new beginnings following an uncertain stint at a West Seattle boardinghouse. There are men who hit on Rosemary, ascribing athleticism to Toby and pledging bicycle gifts that never materialize, and we see only Rosemary’s tears from unseen boorishness. Toby steals and breaks windows with his pals. He puts forth lies. And as Dwight enters Toby’s life, Wolff observes that this minuscule mechanic tries too hard: “No eye is quicker to detect that kind of effort than the eye of a competitor who also happens to be a child.” But Dwight does have a family, including a daughter named Pearl with a prominent bald spot. And just as Rosemary sees possibility in volunteering for idealistic Democratic candidates, she sees an opportunity in Dwight. Much as W.D. Boyce being bowled over by a Boy Scout, effort is enough to plant an acorn for a dubious family tree. Meanwhile, Toby lets loose several “Fuck yous,” memorializing the message into a wall, and gets in trouble with the vice principal. When the vice principal meets with Rosemary, Toby is convinced of his innocence, not unlike Dwight, and the vice principal reveals his own systematic and sanctimonious story of how he quit smoking to buy a Nash Rambler, the very same rickety vehicle that brought Toby and Rosemary to the west.

It is here that the kernel for Dwight’s autocratic adoption of Toby begins to pop with a frenzy of fragile male ego: the belief that laborious effort, even on the most inconsequential acts, somehow makes one a respectable hard-working American. Toby is asked to pick up roadkill. He is asked to wait in a car as Dwight gets plastered in a bar. He is watched as Dwight fuels himself on tugs of Old Crow and Camels. He delivers newspapers and his earnings are pilfered by Dwight. He paints an old Baldwin piano to cover up its chintz. And he is commanded to pluck hard husks of horse chestnuts — a tyrannical tilling with some unspecified life lesson attached in which the product of all this hard labor is never actually used. When Toby gets into a fight with a kid named Arthur Gayle, Dwight coaches him on pugilism, claiming that any defeat is his fault. And throughout all this, there are the weekly Boy Scout meetings. Toby’s plan is to run away from Dwight’s home in Concrete, a Washington hamlet built on shaky slopes that Wolff describes as a graying and dusty landscape with cracking cement banks. It is, like many parts of America even today, a fraying tableau where too much effort gets in the way of existence, disguising the fissures of easily broken lives. One can almost imagine Dwight using the hashtag #MAGA on Twitter had he materialized decades later.

Whether this subjective truth-telling represents a kind of fearlessness or power in its own right is subject to the degree to which you are willing to embrace Wolff’s life story. But it does represent a refreshing alternative to the Horatio Alger grandstanding that too many personal essays wallow in today. (See, for example, most of the material published on Thought Catalog.) David Plotz once chided Dave Pelzer for turning child abuse into entertainment. This Boy’s Life avoids such petty voyeurism, in large part because it nestles Toby’s life and Dwight’s stark assaults by Dwight within the larger American dilemma of how to contend with fakery. And in an epoch where narcissistic dishonesty and “alternative facts” and social media outrage are increasingly the norm, there is a beautiful grace in putting your life out there and not giving a damn how others judge it.

Next Up: Beryl Markham’s West with the Night!

Bechdel: Oh, I think of that Dr. Seuss spread, which was a purely visually driven sequence. I’m talking about one of my favorite childhood books, which was Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book.

Bechdel: Oh, I think of that Dr. Seuss spread, which was a purely visually driven sequence. I’m talking about one of my favorite childhood books, which was Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book.

Correspodnent: Does movement offer a more creative place to establish a character? More so than the backstory, research, or anything?

Correspodnent: Does movement offer a more creative place to establish a character? More so than the backstory, research, or anything? Correspondent: You note of [your future husband] Ben that, as you watched him calmly rub soap into his hands by the communal sink, you realized that you had known all along that you would see him again. I’m wondering what it is about hand hygiene that serves as your personal madeleine.

Correspondent: You note of [your future husband] Ben that, as you watched him calmly rub soap into his hands by the communal sink, you realized that you had known all along that you would see him again. I’m wondering what it is about hand hygiene that serves as your personal madeleine.

Manguso: I thought of the pieces as an arrangement in two phases. The first phase was completely chaotic and the second phase was orderly. And during the chaotic first draft phase, the project that I set myself was really just to try to remember everything I could remember about this nine-year period in my life. Just everything. Every individual memory that I could bring up. And after my latest revision had lasted seven years, after that time, it really did seem that the memories had become particulate. Like there really was just one memory that espoused the insertion of the first central line in my chest. And it really did seem to have hardened in my memory into this item, this thing, this chunk of this chapter. And so while I was first writing the book, I didn’t think about chronology. Mainly because I had no idea how to write a book about one thing. I’d never done it before. And I didn’t know anything about narrative or what should come first. I really just wrote the pages all as individual files. And once I couldn’t remember anything else, I printed them all out and tried to notate based on memory and based on asking people what months and what year each thing had happened. And then I just put them in chronological order.

Manguso: I thought of the pieces as an arrangement in two phases. The first phase was completely chaotic and the second phase was orderly. And during the chaotic first draft phase, the project that I set myself was really just to try to remember everything I could remember about this nine-year period in my life. Just everything. Every individual memory that I could bring up. And after my latest revision had lasted seven years, after that time, it really did seem that the memories had become particulate. Like there really was just one memory that espoused the insertion of the first central line in my chest. And it really did seem to have hardened in my memory into this item, this thing, this chunk of this chapter. And so while I was first writing the book, I didn’t think about chronology. Mainly because I had no idea how to write a book about one thing. I’d never done it before. And I didn’t know anything about narrative or what should come first. I really just wrote the pages all as individual files. And once I couldn’t remember anything else, I printed them all out and tried to notate based on memory and based on asking people what months and what year each thing had happened. And then I just put them in chronological order.

Shukert: Jason Priestly and Fred Savage were the two guys on TV who I had big crushes on as a child. I had a picture of Fred Savage in my locker that I cut out from the newspaper. I remember that he was holding a candy box. Like a Valentine’s heart box. And I would pretend that he was holding it for me. And then when I got a little older, I thought Jason Priestly was the handsomest man I had ever seen. I mean, when I say “a little older,” I mean ten. But I had a big poster of him in my room too.

Shukert: Jason Priestly and Fred Savage were the two guys on TV who I had big crushes on as a child. I had a picture of Fred Savage in my locker that I cut out from the newspaper. I remember that he was holding a candy box. Like a Valentine’s heart box. And I would pretend that he was holding it for me. And then when I got a little older, I thought Jason Priestly was the handsomest man I had ever seen. I mean, when I say “a little older,” I mean ten. But I had a big poster of him in my room too.