- Paramount Pictures Corporation holds co-copyright on David Foster Wallace’s “Host.”

- Nicholson Baker’s first two records, registered in 1981, were for two stories: “Snorkeling” and “K.590.” Both stories have not been collected. But the former appeared in The Little, v. 13, no. 1 and 2, p. 74-81. The latter appeared in the December 7, 1981 issue of The New Yorker.

- George Romero has been busier than you think. Romero is understandably meticulous about copyright — perhaps because Night of the Living Dead was, quite famously, issued without a copyright and entered into the public domain. I’m extremely curious about what 1994’s Jacaranda Joe might have been. There is no reference in the IMDB. This was a 23 page script — presumably for a half hour anthology series. Actor Andy Ussach even has a picture of him and Romero “during the Jacaranda Joe filming.” So if something was shot, was it simply not completed?

- Did Good Man Park author a book on psychological self-defense? This might explain his exclamation marks!

- Will Stanley Kubrick’s Lunatic at Large be turned into something? The entry reads: “Statements re transfer space, address & corres.” More info on this lost treatment here.

- Is it the same Tao Lin who wrote Overconfidence and Asset Prices?

- A screenplay written by Pablo Guirado Garcia called I Pass Like the Night: Serial Fucker based on the Jonathan Ames book?

- I’m curious about Neal Pollack’s play, Chicago on the Rocks. Was it performed?

- I have typed in about twenty-two women into this search engine, but I have unearthed nothing lost or unknown. I find the gender disparity troublesome.

- I could be here all night. Really, I could. There are mysterious works here that were never published or saw the light of day. Some of the copyright documents have mysterious exhibits attached, and I imagine that this is not necessarily the diligence of a cutthroat attorney hoping to protect his client’s interests, but that some of these writers offering eccentric riders to their manuscripts for those who take the trouble to go down to Washington to examine these documents in person. A bonus for anyone wishing to go the extra mile — a consolation prize for the truly obsessed.

- There must be other copyright obsessives out there right now. Perhaps their partners are now in bed and they find the same solace I do typing in search terms into the WebVoyage interface. They may have the same admiration for the neat organization, the helpful annotations throughout the database (“Notes: play”), the specific dates, the letter code which precedes each copyright number (TX for text, V for recorded document, PAu for dramatic work and music; or choreography), and, like me, they may be pondering why the recorded documents have two sets of numerals (VxxxxDxxx).

- Then again, if you work at the Copyright Office, the taxonomic structure with which I am now finding some strange appeal would likely become insufferable. The same way that a file clerk mindlessly puts away files and, in the worst of cases, doesn’t even have the benefit of music. I suddenly have great sympathy for the folks who work at the Copyright Office, particularly those who must ensure that the records are put away accurately. And yet it is the top-tier executives who we pay more money.

- Did the clerks have any say in the way this system was set up? Or were they at the mercy of middle managers who insisted that V had to represent “recorded document?”

- Furthermore, how much time was devoted to typing in all of this data into a computer? Is it really worth the $45 registration fee for all that pain? Or are the top men at the Copyright Office getting a good chunk of that cheddar? Perhaps the clerk spent three minutes typing all of the necessary data into the Copyright Office computer. That means that the clerk should rightly be earning $900/hour. But such an hourly rate is inconceivable. So where does this extra money go?

- I think I will copyright a few things this year myself.

Category / Edward Champion

The Decline of Book Reviewing: A Case Study

It is said that the Eunectes murinus — referred to by laymen as the anaconda or the water boa — spends most of its time shooting its slimy body beneath the water, waiting for a hapless gazelle to stop and take a drink, only to grab the lithe animal with its jaws, coil its scaly muscular husk around its quivering body, squeezing and constricting until the animal is helpless (the animal is never crushed), where it then feasts upon the meat. It does this, because, while the boa does surface on land from time to time, the boa is more taken with the scummy agua. It does not know any better.

And while most mainstream newspaper book sections are devoted to thought over carnivorous instinct, there remain some critics, terrified of inhabiting any topography foreign to their hermetic environments and who remain needlessly hostile to any author crossing multiple ecosystems.

The author in question is William T. Vollmann. And the book is Riding Toward Everywhere, a surprisingly thin volume (by Vollmann standards, at least) that concerns itself with trainhopping and vagrants. (Full disclosure: While the book isn’t Vollmann’s greatest, I did enjoy the book. And while I may be a devotee to Vollmann’s work, I have never let my admiration for the man hinder fair and critical judgment. Above all, I recognize that Vollmann, like any original and idiosyncratic author, must be read on his own terms. This would seem self-evident to even the most elementary reader, because of Vollmann’s style and his distinct subject matter. But other individuals, as I shall soon demonstrate, don’t share this commitment to due consideration.)

The author in question is William T. Vollmann. And the book is Riding Toward Everywhere, a surprisingly thin volume (by Vollmann standards, at least) that concerns itself with trainhopping and vagrants. (Full disclosure: While the book isn’t Vollmann’s greatest, I did enjoy the book. And while I may be a devotee to Vollmann’s work, I have never let my admiration for the man hinder fair and critical judgment. Above all, I recognize that Vollmann, like any original and idiosyncratic author, must be read on his own terms. This would seem self-evident to even the most elementary reader, because of Vollmann’s style and his distinct subject matter. But other individuals, as I shall soon demonstrate, don’t share this commitment to due consideration.)

A number of recent reviews reveal an astonishing paucity of insight and, in some cases, remarkable deficiencies in reading comprehension. And this all has me greatly concerned about the state of contemporary criticism. While there were dismissals from the Pittsburgh Post Gazette‘s Bob Hoover and the Los Angeles Times‘s Marc Weingarten that had the good sense to avoid dwelling so heavily on Vollmann’s peccadilloes, the majority of these negative reviews not only failed to comprehend Vollmann’s book, but appeared predetermined to despise it from the onset. They wished to judge Vollmann the man instead of Vollmann the author. Which is a bit like judging Dostoevsky not on his literary genius, but on his abject personal foibles. Or dismissing Woody Allen’s great films because he married his adopted daughter. This is the stance of blackguards who peddle in gossip, not criticism.

And yet speculation into Vollmann’s character was unfurled in messy dollops under the guise of “criticism” or “book reviewing.”

From Rene Denfeld’s review in The Oregonian:

There is a saying among some bloggers: “I think I just vomited a little in my mouth.”

That’s how I felt reading “Riding Toward Everywhere.”

William T. Vollmann is a mystifyingly respected writer, a man who has made his reputation by exploiting sex workers, the poor and other helpless targets as he plumbs their depths with his supposedly insightful pen, not to mention other appendages.

Well, this blogger has never typed that hackneyed sentence, in large part because resorting to cliches are about as enticing as four hours with a dentist (or, for that matter, dwelling on an essay written by a lazy writer). But then Ms. Denfeld has no problem letting false and near libelous conjecture get in the way of understanding what’s in the text. She fails to cite any specific examples on how Vollmann has “exploited” his subjects. And she has deliberately misread Riding Toward Everywhere to suit her false and incorrigible conclusions. To be clear on this, it was not — as Ms. Denfeld suggests — Vollmann who referred to “citizens” contemptuously, but the vagrants who Vollmann interviewed. Since Ms. Denfeld doesn’t appear to know how to read and infer from a book, here is the specific manner in which Vollmann establishes a “citizen.” Vollmann starts talking to vagrants in search of the notorious gang, the Freight Train Riders of America. Early on in the book, Vollmann approaches a man with a bandana and bluntly asks him, “Are you FTRA?”

You goddamned dufus! shouted the man. That’s the stupidest fucking thing I ever heard. You wanna commit suicide or what? I’m not even FTRA and you’re already starting to piss me off. Don’t you get it? We hate you.

Why’s that?

Because you’re just a goddamned citizen.

Sorry about that, I said. (33)

Denfeld further claims that Vollmann “fancies himself the Jack Kerouac of our times,” but it’s quite evident that Vollmann, in addition to pointing out the differences between hitting the roads and riding the rails, views himself as a somewhat clumsy traveler and does not permit his literary antecedents to define him:

Neither the ecstatic openness of Kerouac’s road voyagers, nor the dogged cat-and-mouse triumphs of London’s freight-jumpers, and certainly not the canny navigations of Twain’s riverboat youth define me. I go my own bumbling way, either alone or in company, beset by lapses in my bravery, energy, and charity, knowing not precisely where to go until I am there. (73)

Denfeld also writes, “His concession to the law is to borrow friends’ cars when he picks up hookers so if he gets caught, it won’t be his license that is lost.”

Again, Denfeld deliberately twists Vollmann’s words around. Here is what Vollmann actually wrote:

My city passes an ordinance to confiscate the cars of men who pick up prostitutes. This compels me to walk….It may well be that I am a sullen and truculent citizen; possibly I should play the game a trifle. But I do, I do: When I pick up prostitutes I use somebody else’s car. (4-5)

It is clear here that Vollmann is being as straightforward as he can about his life, trying to set down personal fallacies he may have in common with his subjects. It would be one thing if Ms. Denfeld stated the precise problems she had with the book, but she remains so fixated in her happy little universe — which involves living with her partner with three adopted children and OMG! “teaching writing in low-income schools and volunteering in adoption education and outreach”; could it be that Vollmann is not the only “rich” person who “brags” about philanthropy? — that she can’t seem to consider that other people relate to the world a bit differently. And it’s clear that she can’t be bothered to engage with the issues that the book presents. Masticating upon this book, good or bad, seems beneath Ms. Denfeld’s abilities. Beyond Ms. Denfeld’s consistent failure at basic reading comprehension, I likewise remain gobsmacked that these flagrant errors, easily confirmed by checking Ms. Denfeld’s statements against the text (which runs a svelte 186 pages), were allowed to run in a major newspaper.

It is clear here that Vollmann is being as straightforward as he can about his life, trying to set down personal fallacies he may have in common with his subjects. It would be one thing if Ms. Denfeld stated the precise problems she had with the book, but she remains so fixated in her happy little universe — which involves living with her partner with three adopted children and OMG! “teaching writing in low-income schools and volunteering in adoption education and outreach”; could it be that Vollmann is not the only “rich” person who “brags” about philanthropy? — that she can’t seem to consider that other people relate to the world a bit differently. And it’s clear that she can’t be bothered to engage with the issues that the book presents. Masticating upon this book, good or bad, seems beneath Ms. Denfeld’s abilities. Beyond Ms. Denfeld’s consistent failure at basic reading comprehension, I likewise remain gobsmacked that these flagrant errors, easily confirmed by checking Ms. Denfeld’s statements against the text (which runs a svelte 186 pages), were allowed to run in a major newspaper.

Ms. Denfeld isn’t the only venerable nitwit assigned to review a book outside her ken. Here’s the opening paragraph from “respected” author Carolyn See’s takedown at the Washington Post:

William T. Vollmann is revered and venerated by a lot of men whose brains and souls I deeply respect. They love his ideas, the sheer length of his work (one book of his, “Rising Up and Rising Down: Some Thoughts on Violence, Freedom and Urgent Means,” runs over 3,000 pages); they love his freedom and eccentricities — he’s been to and written about Afghanistan, the Far East and the magnetic north pole, and has spent vast amounts of time with prostitutes while also managing to keep a wife and kid. He seems to be a man of prodigious abilities. At the same time, I can say I’ve never had a conversation with a woman about his work. He just doesn’t seem to come up on our radar. Is it that we don’t have the time to read 3,000 pages? That we don’t care as much as we should about the magnetic north pole? I don’t know.

Rather then dredge up my own empirical evidence of women I know who do read and enjoy Vollmann in response to this egregious sexism, which is particularly ignoble coming from a Ph.D., I’ll simply presume that See’s sheltered life at UCLA, much less basic library skills, precludes her from consulting such books as Linda Gregerson’s Magnetic North (Houghton Mifflin, 2007), Kathan Brown’s The North Pole (Crown, 2004), or Helen Thayer’s Polar Dream: The First Solo Expedition by a Woman and Her Dog to the Magnetic North Pole (NewSage, 2002). Further, Laura Miller’s womanhood didn’t hinder her from devoting 2,000 words to Poor People, pointing out (although critical) that Vollmann was “a writer of extraordinary talent.” Dava Sobel called him “ferociously original.” Numerous other examples can be readily unearthed in newspapers and academic journals. Vollmann is no more an author just for men than Jennifer Weiner is an author just for women. And only a fool or a John Birch Society member would declare otherwise.

See’s prefatory paragraph, of course, has nothing to do with the book in question. And if See had been a responsible reviewer, she would have recused herself from reviewing an author who “doesn’t come up on [her] radar.” An ethical and responsible reviewer knows her own intellectual or perceptive limits.

And then there is J.R. Moehringer’s offering in yesterday’s New York Times Book Review. Like Denfield, Moehringer has reading comprehension problems, although thankfully not as severe. Moehringer completely misses Vollmann’s point that Cold Mountain is, much like Shangri-La, an unobtainable destination, although he does seem to understand that it’s “a nonexistent mountain.” But for Moehringer, “the words lose all meaning.” It doesn’t occur to Moehringer that Vollmann’s repetition of “Cold Mountain” might be a way of expressing the ineffable or the unfindable. Or as Vollmann puts it:

I stood here wondering if I had reached Cold Mountain. Where is Cold Mountain, anyway? Isn’t it for the best if I can never be sure I’ve found it?

But Moehringer’s biggest sin is to ask Vollmann the hypothetical question, “Pal, what the hell’s wrong with you?” He finds Vollmann crazy for “get[ting] his kicks breaking into rail yards and hopping freight trains,” and wonders why nobody has caught him. But he fails to consider that Vollmann’s romantic description of the open air or the modest code of honor that prevents a fellow hopper from stealing another hopper’s sleeping bag might hold some appeal to a man of Vollmann’s eccentricities. Clearly, there are reasons why Vollmann hops trains. And Vollmann dutifully explains why. But since Moehringer lacks the intellectual flexibility to understand this, he breaks John Updike’s first rule of reviewing (“try to understand what the author wished to do, and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt”) at the onset.

He declares Vollmann “miserable” and “filled with irredeemable gloom about the state of the world,” wondering how anyone could feel this way more so than others, but fails to recognize that one of the major thrusts of Vollmann’s work has been to chronicle the misunderstood. Kindness and empathy, and writing about people that other novelists and journalists are all too happy to ignore, are at the core of Vollmann’s output. Further, there is more to Vollmann’s mantra than Cold Mountain. As Vollmann explains:

I am sure that the fact that my wife had expressed her wish for a divorce two days before had nothing to do with the fact that I kept saying to myself: I’ve got to get out of here. I’ve got to get out of here.

Moehringer also writes, “Early on, Vollmann mentions ‘a Cambodian whore’ he nearly married. Why? No reason.” But what Moehringer conveniently elides is how Vollmann mentions this in connection with taking a bus trip out to Oakland. When the bus stopped at Cheyenne, Vollmannn felt that he had reached “true West.” He did not get out of the bus, but he felt that “Cheyenne changed me at that moment.” And if Moehringer is so indolent a reviewer that he cannot grasp the basic concept — indeed, the specific “reason” Vollmann is bringing up this anecdote — of how one decision often changes a life at a crossroads, let us consider the specific passage:

Once upon a time I almost married a Cambodian whore, or at least I convinced myself that I was on the verge of wedding her; once I considered moving in with an Eskimo girl; in either case, I would have learned, suffered and joyed ever so intensely in ways that I will never know now. And what if I had gotten off the bus in Cheyenne in the year of my youthful hope 1981? California is only half-western, being California. Cheyenne is one hundred percent Western….And had I stepped off the bus in Cheyenne, I might have become a cowboy; I could have even been a man.

If Moehringer — a Pulitzer Prize winner, for fuck’s sake — is incapable of seeing the reason why Vollmann mentioned the incident, then I shudder to consider his dull worldview and nearly nonexistent sense of adventure. Why climb Everest? No reason. “Because it’s there.”

All three reviewers demonstrate a remarkable devotion to remaining incurious and to condemning an author personally rather than trying to consider an author’s perspective. Small wonder, given this reactionary clime, that book reviewing sections face extinction.

Night at the Boxcar

This was roughly the view you received if you had the privilege of attending the Boxcar Lounge on Wednesday night. The venue was indeed shaped like a boxcar and it was SRO for those souls, like Levi and me, who had arrived from McNally Robinson. (Of that counterprogramming, while John Freeman made a valiant attempt to ask questions of Lee Siegel that would cause him to think instead of fulminate more on his puerile anti-Internet views, the two of us left after twenty minutes. Siegel, as a speaker, has the voice of a semi-squeaky plush toy that still has a bit of air left, but hasn’t yet figured out that the tots have moved on to newer baubles. I had seen this kind of arrogant and opinionated blather before when the speaker had referred to itself as Andrew Keen. So there was no need to subject myself to it again. To offer a small sample: According to Siegel, the Internet is apparently composed of 80% porn. And while it’s absolutely diabolical for people to leave anonymous and hateful comments (as they did for Siegel’s posts at the New Republic), apparently it’s perfectly peachy keen for Siegel to impersonate “sprezzatura” because there is nothing forbidding such a cheap impersonation under journalistic rules. Never mind that Siegel’s shenanigans were hardly transparent and had to be ferreted out by top brass at the New Republic. I took notes, but I felt like I was transcribing a kindergarter’s efforts to discuss Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason based on a one-sentence summary. As such, my notes are not worth reproducing or summarizing.)

You couldn’t get a seat at the Boxcar Lounge. Unless you were one of the smart ones, like Maud and her friend, who arrived early to get a seat. There were many bloggers in the crowd, including Jason, Levi, Marydell, Lauren, and Sarah. It was also a pleasure to talk with Michael Orbach, Jami Attenberg, and a number of other people who I will no doubt remember after I hit the “Publish” button. I’m sorry.

Besides, who needed Siegel when there was another installment of Jami Attenberg’s Class of 2008 Reading Series going down? This one featured Michael Dahlie reading from A Gentleman’s Guide to Graceful Living, Lynn Lurie reading from Corner of the Dead, and (pictured above) Ceridwen Dovey reading from Blood Kin. Dovey was one of the evening’s standouts. Her reading was quietly intense and suitably genteel, and I am now most curious about her novel.

And then there was Mr. Sarvas himself, who read from a chapter of his forthcoming novel, Harry, Revised: the infamous incident in the bookstore. The chapter contains a disparaging reference to David Foster Wallace and I felt compelled to cry out a “Yea!” in DFW’s defense. Mark likewise felt compelled to point to me during this moment.

Is Harry, Revised any good? I was a bit hesitant to approach it, as my candor compels me to tell even my closest friends when their work is not up to snuff. But I have read the whole of Harry, Revised and I can recommend it. Mark has ventured down a somewhat unexpected path here, unafraid to have his protagonist enter into uncomfortable territory. The book’s style displays Mark’s clear love for Fitzgerald and there is something of a French farcical feel that permits material that should not work to be executed with a crazed grace.

I am sorry to report, however, that there remains one passage that will almost certainly be nominated for The Bad Sex Award. But you’ll have to wait for a forthcoming installment of The Bat Segundo Show to find out precisely what it is.

Interview with Charles Burns

Four new podcasts were released today at The Bat Segundo Show. And since we’re on the subject of Segundo, what follows is a short excerpt from my conversation with Philadelphia-based artist Charles Burns, who I chatted with during a recent visit through New York.

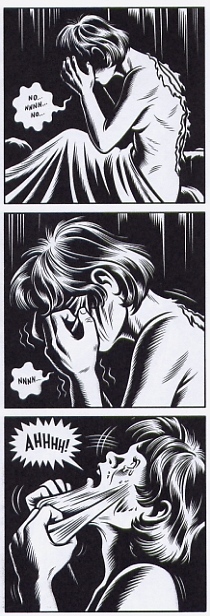

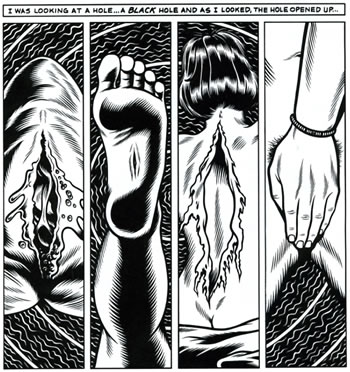

You might know Burns’s work from his advertisements or his illustrations for The Believer. But he’s best known as the writer and illustrator of the graphic novel, Black Hole, a compilation of his twelve-volume comic book. Burns worked on this over the course of ten years. And one of its remarkable qualities is the way that it remains remarkably consistent in its tone, despite the fact that Burns saw his two daughters grow up as he patiently put his work together. Black Hole depicts the story of a sexually transmitted disease that afflicts various teenagers in the Pacific Northwest. The work is very much a Rorschach test for the reader. One might infer a parable about AIDS or, if you wanted to get really reductive, innocence lost. Or it can be simply enjoyed as a dark tale of American adolescence gone awry.

You might know Burns’s work from his advertisements or his illustrations for The Believer. But he’s best known as the writer and illustrator of the graphic novel, Black Hole, a compilation of his twelve-volume comic book. Burns worked on this over the course of ten years. And one of its remarkable qualities is the way that it remains remarkably consistent in its tone, despite the fact that Burns saw his two daughters grow up as he patiently put his work together. Black Hole depicts the story of a sexually transmitted disease that afflicts various teenagers in the Pacific Northwest. The work is very much a Rorschach test for the reader. One might infer a parable about AIDS or, if you wanted to get really reductive, innocence lost. Or it can be simply enjoyed as a dark tale of American adolescence gone awry.

Since Burns has conducted many interviews for his magnum opus, the challenge was to come up with a few conversational angles that he hadn’t encountered. But the interview frequently drifted into abstract personal memories when I asked him about a specific facet of Black Hole, demonstrating perhaps that artistic ambiguities aren’t always so easily pinpointed.

Correspondent: You’ve probably seen Vanessa Raney’s really lengthy critical essay of Black Hole, where she analyzes your panels quite in-depth. And I actually wanted to ask you about a comparison she made. She pointed out that Keith, Chris, and Eliza actually represent the same relationship structure in Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit. And I wanted to ask you about this. Was Sartre ever on the mind in concocting this narrative? How did the relationship structure begin?

Burns: Boy, that’s a good question. I don’t know that I’ve read the essay that you’re referring to. But there have been some questions asked along those lines before. It really wasn’t an influence or that wasn’t in my mind when I was creating the story. I guess I was trying to create these characters. Two very different types of women. The main character is just coming to terms with the differences between them and his attraction to them. His initial attraction to Chris, a girl that he admires from his biology class, is this very kind of clean-cut — what he thinks is kind of clean-cut. The kind of woman that he’s putting on a pedestal. She’s perfect. But he doesn’t really know anything about her at all in reality, other than just that she seems amazing.

And then he meets a very different kind of woman, who’s very much earthy. Much more sexual. And he finds himself attracted to her, much to his dismay. So the story’s really his coming to terms with his reaction, I guess, to these different women.

Correspondent: But no Jean-Paul Sartre.

Burns: No.

Correspondent: Any literary…

Burns: I would love to be able to say that there’s a good comparison there. But, no, that wasn’t the case.

Correspondent: Okay. I also wanted to ask you about some of the anatomical close-ups throughout Black Hole. They remind me very much — in addition to the pustules and the various biological impediments that many of the characters have — it reminds me very much of the sort of World War II venereal disease films.

Correspondent: Okay. I also wanted to ask you about some of the anatomical close-ups throughout Black Hole. They remind me very much — in addition to the pustules and the various biological impediments that many of the characters have — it reminds me very much of the sort of World War II venereal disease films.

Burns: (laughs)

Correspondent: I was wondering. What kind of visual references did you use for these particular decisions? Or was it just more of an intuitive choice?

Burns: It was probably more of an intuitive choice. I mean, there’s those things that I grew up that are out there. I think there’s references in the movie to sitting in the biology health class and looking at — learning about sexuality that way. There’s was always this kind of very strange antiseptic situation. I remember one time in biology class, there was — I guess, what do you call it? — a TA. A student teacher. And there was some film on — I don’t know, reproduction. And she showed the first half of it. And then she abruptly turned the film off. And, of course, everybody in the class said, “Oh, keep running it! We want to see it again! We want to see the rest of it.” And she would say, “No, no, no, no.” And finally she turned it back on. And there was this very graphic portion of the movie, where we were seeing an IUD inserted into a vaginal — (laughs)

Correspondent: Yeah.

Burns: And everybody just immediately got very, very quiet and very, very uncomfortable. Because here’s this — suddenly after seeing these very typical movies about “Your Growing Body,” suddenly we were seeing these very graphic representations. It was an odd moment.

Correspondent: Is it something about that period between, say, 1945 and 1975? Was that very much on the mind — in terms of getting this particular look? Or this particular emphasis on close-ups and warts and the like?

Burns: I don’t know. I guess that’s more of a personal thing. I guess that’s just how my brain works or thinks. Those were the kinds of images that were coming up. Again, it has to do with all the things that you’re subjected to and that you come across from that time period. But nothing as thought out as that, no.

Correspondent: So really it’s more of a personal intuitive experience that you’re drawing upon here? I know…

Burns: That would be a better description.

Correspondent: Yeah, because this leads me into another question. I know that the yearbook photos, or rather the photos on the inside cover, were taken from your own yearbooks.

Burns: Yeah.

Correspondent: And this leads me to ask you about how much of what is in Black Hole is taken from your personal experience, and where do you imagine certain details. I mean, certainly, the disease which plagues all these various people is imagined in some sense. But I’m wondering, in terms of the more personal observations, were these taken more from anecdotes? Were these imagined? On what level did you feel the need to draw upon real life and your own instinct for reimagining behavioral scenarios?

Burns: I mean, my situation growing up was a much more benign situation than what I’m depicting. I mean, there were internal struggles that I was going through, that I think everybody goes through during adolescence, that seemed extremely dramatic and extremely heartrending, difficult times. And I guess I was trying to depict that. What those feelings were. The kind of internal struggle that I was going through.

There are certainly situations in the story that are drawn directly from my life. I never met a half-naked girl with a tail.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Burns: I would have loved to.

Correspondent: Wouldn’t we all really?

Burns: That never happened. My existence was much more sedate and pedestrian, I suppose. But again, these sorts of things were brewing in my mind. My sense of not fitting in. My sense of this kind of internal horror that I was feeling in a lot of situations. Whether they were anywhere near…

Correspondent: Well, in terms of personal experience vs. what you observed, I mean, it seems to me that personal experience is more the motivating impetus for what you put into Black Hole more than anything else. If what I’m understanding you to say is correct. Were you more of an observer or were you one of those types of people?

Burns: I was one of those types of people in varying degrees. Someone was asking me the other day, “Were you a punk?” I was there in all those concerts participating, but I never shaved my head or carved a swastika on my forehead. But yeah, I was there. I guess that’s what I wanted to do too — in the book, talk or just have a realistic look at the times I was growing in. There’s moments in there, even though they’re very sedate, that are very horrific to me. To be sitting in a room for four hours listening to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon get played over and over, and sitting around with a bunch of guys for hours and hours, is horrific to me.

[The full interview will appear in a future installment of The Bat Segundo Show.]

The Video Game as Art

In 2005, film critic Roger Ebert ruffled a few feathers when he suggested that because video games require player choices, games are therefore an inferior medium:

To my knowledge, no one in or out of the field has ever been able to cite a game worthy of comparison with the great dramatists, poets, filmmakers, novelists and composers. That a game can aspire to artistic importance as a visual experience, I accept. But for most gamers, video games represent a loss of those precious hours we have available to make ourselves more cultured, civilized and empathetic.

I can certainly agree with Ebert that video games are, for the most part, showcases for the latest gaming engines, primarily designed so that the individual will drop hundreds of dollars for a next-generation console system or a needlessly expensive video card that will be outdated in a few years (only to be replaced by yet another). We are now in the nickelodeon days, although, as the Wii demonstrates, the game controllers are getting more interesting. But this multi-billion dollar industry is less concerned with the human experience than it should be. It has come close with the Civilization games and the Sims offerings, and may come even closer with Will Wright’s much delayed Spore, an ambitious god game that permits the player to develop a cell and then control the natural development of this cell into a species, and then further manage the species as it plunges into space exploration. I’ve lost many hours feeling an ignoble cathartic thrill when fragging a junior-high schooler who, like me, should probably be reading a book. But I can justify my shameful vicarious pleasure by knowing that this is a medium that has yet to produce a Battleship Potemkin or a Birth of a Nation.

I can certainly agree with Ebert that video games are, for the most part, showcases for the latest gaming engines, primarily designed so that the individual will drop hundreds of dollars for a next-generation console system or a needlessly expensive video card that will be outdated in a few years (only to be replaced by yet another). We are now in the nickelodeon days, although, as the Wii demonstrates, the game controllers are getting more interesting. But this multi-billion dollar industry is less concerned with the human experience than it should be. It has come close with the Civilization games and the Sims offerings, and may come even closer with Will Wright’s much delayed Spore, an ambitious god game that permits the player to develop a cell and then control the natural development of this cell into a species, and then further manage the species as it plunges into space exploration. I’ve lost many hours feeling an ignoble cathartic thrill when fragging a junior-high schooler who, like me, should probably be reading a book. But I can justify my shameful vicarious pleasure by knowing that this is a medium that has yet to produce a Battleship Potemkin or a Birth of a Nation.

To suggest, however, that the video game will never find the same gravitas as cinema is to fall prey to same prejudicial thinking with which intellectuals once castigated cinema in the early 20th century. Let’s not forget that it took the motion picture around thirty years of technological developments before it was considered more than a gaudy amusement. And we have only just passed the 30th anniversary of the Atari 2600.

This New York Times article from September 7, 1913 suggests that the then primitive motion picture was, like the contemporary video game, very much about delivering spectacle to a mass audience. George Kleine, one of the key people who established the film industry in the United states and who had just made a cinematic adaptation of Quo Vadis? with a cast of 3,000 people (then an unprecedented number), is quoted in an eerily comparable manner about the future of the medium”

“I have plans for the future which make everything I have done so far seem to be mere child’s play. The educational end has not begun. Motion pictures will not supplant books in the public schools, according to my opinion, but they will revolutionize our educational system. Instead of being bored, the child will enjoy learning by object lessons conveyed by the use of moving pictures.”

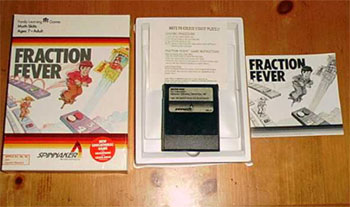

Replace “motion pictures” with “video games” and you essentially have what’s reflected in this 2002 BBC News article, in which a study reveals that games are not a substitute for books, but a way to help children learn. And if, like me, you grew up playing Fraction Fever (the ROM is here, if you’re an emulator geek) or any of the other Spinnaker titles, perhaps there is some credence to these theories.

Replace “motion pictures” with “video games” and you essentially have what’s reflected in this 2002 BBC News article, in which a study reveals that games are not a substitute for books, but a way to help children learn. And if, like me, you grew up playing Fraction Fever (the ROM is here, if you’re an emulator geek) or any of the other Spinnaker titles, perhaps there is some credence to these theories.

There is also this commentary from the 1913 article:

There are many pictures being thrown upon the screen every day which, although not really harmful, possess no merit. Some are positively ridiculous, and portray scenes both unnatural and unreal. It is not to be expected, however, that with the demand for films exceeding the supply every production should be perfect.

It seems to me that Ebert’s Grumpy Old Man routine was published in newspapers a century before. The medium is the only thing that’s different.

Jason Rohrer’s surprisingly touching game, Passage, freely available for download and released a few months ago, quite easily destroys Ebert’s thesis that the video game is incapable of poetry. Rohrer achieves a unique poetry both in limiting the player’s perspective to a 100×16 window and through the deceptively simple manner that he has designed this game for the player. Play the game once and you will follow a strapping young man from left to right. He finds a woman along the way. A pixelated heart soon follows. As the man advances further along this horizontal tableau, he (and his sweetheart) begins to age. He goes bald. As he continues to age, his position on the axis shifts further to the right. Near the end of his life, he is hobbling. Then a tombstone crops up. The End.

Or is it?

The game isn’t limited to left-to-right movement. Play the game again, press the down arrow. and you will find yourself exploring a maze below the top, collecting many stars and stumbling for a way out. But with this simple design, Rohrer has done something very interesting. If you choose to fall in love with your sweetheart, the two of you can only explore certain areas. Because with your partner in tow, you collectively take up a wider space and can only fit into specific territory. If you choose to go through this life solo, then you’ll be able to collect many of the stars denied you and your sweetheart, but you may get lost in the maze and be unable to find your way back to where your sweetheart waits.

If Passage is not quite the video game’s answer to The Waste Land, Rohrer’s poetic game demonstrates that independent developers can in fact use the form in favor of human experience. Rohrer’s lo-fi approach is a welcome response to high-end graphical tentpole operations. I found myself thinking of all the choices I had made over the course of my life and wondered how I would have turned up if I had made slightly different decisions. Contra Ebert, I did indeed find the experience to make me more curious and empathetic about the human condition. (And this would appear to have been Mr. Rohrer’s objective.) This was something that no amount of fragging had inspired.

If all this sounds fishy, well, the game simply has to be played. Like any work of art, it is something better experienced than talked about. And it requires that superannuated naysayers keep open minds.