On Wednesday night, there were two press screening options in New York. The dichotomous choice fell along gender lines. One involved three verbs slammed together in the title and starred Julia Roberts. I had the feeling that it would anger me. The other one involved an aging action star who was still inexplicably given millions of dollars to make movies. Presumably his movies had made money or he was highly persuasive. Since I was too lazy and too busy and too hazy to decide, I naturally went with the choice carefully marketed to appeal to the bulge I was born with, that mighty chorizo contained within my boxers. But because I am committed to the truth, I am sorry to report that I could not summon up an erection during the entirety of The Expendables. I have failed my fellow men. Either that or I have an independent mind.

It’s quite possible that I was distracted by the fact that the 65-year-old Kurt Loder (a man who has, rather sadly, pretended to be young for half his life) was sitting nearby. Loder was there watching (reporting for MTV?) a movie co-written and directed by a 64-year-old action star (also starring) who was trying to recapture his former glory. The irony had not escaped me. It’s quite possible that I was distracted by the rather cheesy-looking CGI dismemberment — a stylistic tic that Stallone had carried over from his last film, Rambo in Denial: Death to the AARP.

But the truth is that I had hoped for more masculinity. More style. More the orphaned action movie I had grown up watching. I expected fading action stars to shoot hard bullets into silly supporting characters and demonstrate their right to cinematic existence by channeling some entirely unforeseen element from a hackneyed script. Dolph Lundgren, for example, redeeming himself for being forced to appear in Universal Soldier: Regeneration. In The Expendables, Lundgren does have a great moment when he stomps a man’s head, the bootprint still visible on his dead opponent’s face, with Lundgren simply replying, “Insect.” But for the most part, Lundgren’s character is fairly useless to the team and negligible to the movie. Yes, there’s a minor scene in which Stallone meets up with Bruce Willis and Arnold Schwarzenegger. But the scene is so poorly written and pointless that it feels more like a contractually obligated Planet Hollywood commercial filmed fifteen years too late.

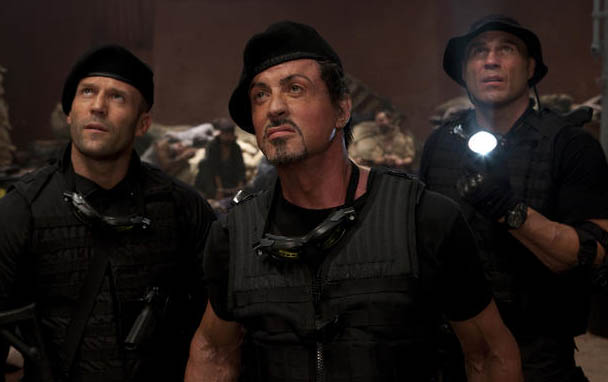

I expected men to ride highly efficient killing machines and display an expertise in weapons and destroy mighty topographies in five minutes. But what has Stallone done with The Expendables? Well, he (with fellow Expendable Jason Statham) sets a pier on fire after spilling two lines of fuel from an airplane and igniting the charge. Is that really manhood? Not in my book, if the lessons I learned from VHS are anything to go by. A real man kills twenty men with his bare hands or, if he must, uses weapons with style. And he does it on the ground. Stallone and Statham have to do it from an aircraft. That’s not manhood. That’s cowardice.

Statham does, however, have a rather hilarious moment that pretty much sums up what this film is: namely, a big-budget Golan-Globus homage. Statham, seeing that his former girlfriend has been given a shiner by the man she’s now with (this movie, needless to say, isn’t kind to women: one even gets waterboarded), tracks down the abusive man at a basketball game. He punches the man repeatedly in the face, grabs the basketball, kills it with a knife, and then says, “Next time I’ll deflate all your balls,” while laying on top of him with the blade. And it’s silly juxtapositions like this keep The Expendables a somewhat fun diversion for anyone who once raided the action movie section at a 1980s video store. But for some inexplicable reason, The Expendables doesn’t quite have the courage to go over-the-top. A car chase sequence that should be either silly or preposterously derivative, featuring Jet Li shooting a machine gun in the trunk of a truck, is merely ho-hum. The conclusive hacienda battle wishes to mimic Commando‘s gloriously violent finale. But in Stallone’s hands, it just feels perfunctory.

And let’s face the hard truth. I don’t hate Stallone. But as a director, Stallone isn’t nearly as interesting as Mark L. Lester or the late George P. Cosmatos. What makes a film like Cobra (starring Stallone, directed by Cosmatos) unintentionally entertaining is the bizarre backlighting when the cult is practicing. Yes, it’s a failed artistic choice. But it is a choice. And you have to give Cosmatos credit for trying something different. (Same goes for the exploding soldier near the end of Rambo: First Blood Part II. No, it doesn’t work. But why on earth does Cosmatos bother to build up the tension when this soldier can’t even shoot straight? If you’re anything like me, you’re left wondering about Cosmatos’s strange artistic decisions for years.) Even Lester’s Showdown in Little Tokyo (which shouldn’t be nearly as entertaining as it is) managed to get several funny moments from Dolph Lundgren, an actor who is hardly known for his range. Indeed, with Lundgren so thoroughly wasted in The Expendables, one wishes that Stallone would have done the gentlemanly thing, getting Lester some much-needed work (that is, if Lester’s presently scattershot credits on the IMDB are any indication).

Within these mostly forgotten action movies from two to three decades ago (and not just the ones made by Cannon), there are failed yet interesting efforts to create cinema. There are filmmakers attempting to exert voices, to offer personalities. The guys making these movies are truly having a ball, even when they are making disastrous movies. And what makes The Expendables so frustrating at times is that it wishes to honor these films without putting itself on the line.

The only actor in The Expendables who seems to understand what’s going on is Eric Roberts. This shouldn’t be a surprise, seeing as how Roberts cut his teeth on silly movies like Best of the Best and Blood Red and he is cast (thank you, Stallone!) as the bad guy. Roberts is one of the few working actors whose scenery-chewing appetite only grows with age. That’s intended as a compliment. I’m convinced that if you threw Eric Roberts into the middle of a soporific art house movie, he’d figure out a way to get the pretentious actors to up their game and he’d certainly get the audience awake. If you give the man an apple to smell, as Stallone is good enough to do, he will find a melodramatic way to signify its presence. In The Expendables, Roberts’s character enters the movie shooting a man and uttering the line, “Now I can see inside of him. And I see lies.” Preposterous, right? Absolutely. In the hands of any other actor, this moment would be disastrous. But Roberts manages to sell it. Because Roberts is smart enough to understand that contemporary cinema presently has a paucity of melodramatic villains — which, incidentally enough, was the action movie’s (circa 1989) bread and butter.

I can’t say that I hated The Expendables. But if you really want a lively action flick, you’re better off with Mesrine: Killer Instinct (coming out on August 27th), a must-see gangster movie with a fantastic performance by Vincent Cassel which I’m hoping to find time to write about. If anything, The Expendables has caused me to unintentionally come out as a cheesy action movie fan. Well, so be it. But when a movie causes you to remember its predecessors and its influences, is it really a movie to remember?