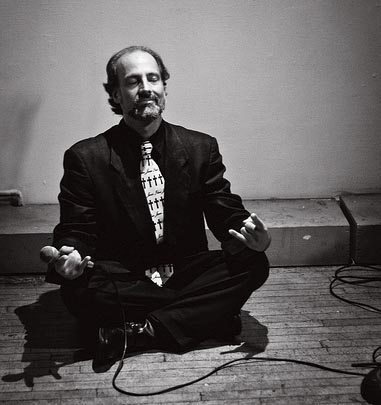

John Banville and Benjamin Black appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #407. Banville is most recently the author of The Infinities. Black is most recently the author of A Death in Summer.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Doubting that his alter ego is the work of a craftsman.

Author: John Banville (aka Benjamin Black)

Subjects Discussed: Efforts to sandwich two men into one voice, why John Banville hates his own books and likes the Black books, the quest for perfection, the sentence as a working unit, Beckett’s “Fail better,” why perfection can’t be fun, how a phrase like “louring turrets” manages to sneak its way into a Benjamin Black novel, craftsmen vs. artists, typing out terrible Joyce pastiches as a teenager, mimicking previous texts, Banville’s early flirtations with commercial fiction, The Untouchable as prototypical Black, fictional ghettos, literary fiction as a ghetto, compartmentalizing fiction, Henry James being forgotten, the decline of Beckett’s reputation in recent years, Donald Westlake’s Memory, the Parker novels, Georges Simenon, The Postman Always Rings Twice and Ulysses as respective masterpieces, Joanna Kavenna’s recent New Yorker essay, thematic commitment, mystery and sociological ambitions, Frank Kermode’s The Sense of an Ending, why Banville and Black bifurcated, the origins of Christine Falls, reaching a mass audience, The Sea, The Book of Evidence being shortlisted for the Booker, the best “reviews” originating from regular people, the disastrous status of being a “writer’s writer,” Hay-on-Wye as a writer’s nightmare, ebooks, [21]

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Banville: People constantly tell me things about my books that I don’t know, that I wasn’t aware of doing. But of course I did them. But I try not to plan. I try not to make links. I try to let a certain seeming incoherence — I try to work in a process of seeming incoherence, trusting that my subconscious or unconscious or whatever it is or just the sentences themselves will make the connections, will make the sense. Art has to be organic. It has to grow of itself. You can plan a certain amount, but the greatest effects in a novel or a painting or a symphony or whatever will always be the bits where the artist lost control. I don’t mean that he lost control of his material, but lost control of what he was doing. You know, the moment where you let something happen is an extraordinary moment.

Correspondent: You suggested that you don’t do that now. Did you do that before?

Banville: Well, I thought — I imagined that I was working according to strict rules. I mean, my book Kepler is divided into — it’s a system that mirrors Kepler’s system of the universe in five perfect solid states between the orbits and the planets and their twenty sides. It was immensely complicated. That was a way of working then. It was useful for me. I couldn’t work like that now. I wouldn’t want to.

Correspondent: Was it the speed? Or the fact that things became too complex? Or that it felt truer and more original to not plan?

Banville: I just got older. And my work methods changed. I changed. I began to realize that I didn’t know everything about the world. You know, the old thing: the older you get, the older you realize how little you know. And that is true. And that’s a very good thing for an artist, I think. That humility before the material, before the world.

Correspondent: The degree to which you ensure that you don’t use the same phrase and the same word in a manuscript — especially on the Banville side. What do you do? Is this a part of the process as well? ‘Cause I’ve noticed that, especially when a ten cent word shows up in the Banville books, it has its one appearance very often from book to book to book. What do you do to ensure that you don’t repeat yourself?

Banville: I take great care. I mean, this is the process of writing. You know, it’s just — it’s what I do every day. I’ve been doing it for fifty years now. So to a certain extent, I come naturally to being careful. But I still find silly things. Especially when I’m doing public readings. Like “Oh God. Look, I used that word at the bottom of the page. At the bottom of the page.” One can never be — as we began by saying, perfectionism is not of this world.

Correspondent: What of distractions? I did read one interview with you where you claimed you were addicted to email. Every thirty seconds.

Banville: Oh god yeah. I’m absolutely addicted to email. It’s become part of the rhythm of writing now. Checking my email. It’s pathetic. My wife got me a postcard to stick on my wall. This is a guy staring at a blank screen. And just on the screen, you’ve got “You haven’t got any fucking emails.” (laughs)

Correspondent: I suppose Twitter or something like Google Plus would be out to lunch with you.

Banville: I can’t. I can’t.

Correspondent: Or Facebook for that matter.

Banville: I can’t possibly let myself to any of those. Emails are quite enough. Well, emails are like the postman coming to your door every thirty seconds. Thirty seconds is a bit much. But there is that sense when you’re sitting there and you’re staring vacantly. “Oh! I haven’t checked my emails in at least ten minutes!”

Correspondent: The reviewer for the Los Angeles Times called this book “a brainy beach read.” How does that sit with you?

Banville: (despondently) Oh. Thanks very much.

Correspondent: Are you comfortable with the idea of “a brainy beach read” or “a beach read” for that matter? Is that the mark of a craftsman?

Banville: Oh yes, I would think so. That’s a compliment, I suppose. It will put people off, of course. But I wouldn’t, you know — you see, I have far more regard for the reading public than I think many publishers have and that many book reviewers have. People know what they want. If they want some piece of easy reading, they’ll buy that piece of easy reading. If they want something else, they’ll buy that. It will often be the same reader who will buy these at different times. So, yes, I’d love to think that people will take this book to the beach. I’d love to think that they’d take a Banville book to the beach. You know? It wouldn’t kill them.

Correspondent: Near the end of The Infinities, you have your wily narrator say, “Dogs are living creatures. Do not speak to me of their good sense.” And in 2009, you wrote about your Labrador for The Guardian. “How is one to write about a family pet without plunging feet-first into a slough of bilge and bathos?” I’m wondering if dogs represent an aspect of our lives, an aspect of living, that to some degree is almost incompatible with words. Is bathos one of those human qualities that sometimes fells John Banville, but that Benjamin Black may be able to pick up some sense of fluidity?

Banville: Well, I think dogs are extraordinary creatures. I mean, animals are, it seems to me, one of the great tragedies of the modern age is that we’ve almost lost contact with the animal world. We treat them as if we are masters of the universe, as if they’re just autonomous. Descartes, of course, has a lot to answer in that regard. Animals, to me, are endlessly fascinating. My wife has a dog at the moment. I think it’s the most magical creature I’ve come across in a long time. A big goofy dog. It came from a long line of dogs who worked on farms. He can’t believe his luck to be in the lap of luxury in our house. Clever, silly, funny, playful. I mean, don’t get me started on dogs. They’re wonderful creatures. But in the wider aspect, people often talk of me as being a postmodernist writer, which is nonsense. Although I think that’s a term that’s falling out of use now — thank god! Because it doesn’t really mean anything. But if I were to describe myself as anything, I would be post-humanist. In that I do not see humans as the center of the universe. My characters are characters that are landscapes. And the world that I create — that Banville creates and that even Black creates — is just as important as the people inhabiting it. This is a hard thing to accept, but it’s true for me. The world, for me, is a living object. And we happen to be viruses on it. The most successful virus the world has ever known. And, of course, a miraculously gifted virus. Look at the things we’ve done. For every Hitler, there’s a Beethoven. We have done miraculous things. But we’re still not as far away from the animals as we’d like to think we are. There’s this notion, which is latent in our minds, that at some point in the evolutionary scale, we took us through a skip. We took a step upwards that separated us from the animals. That we are now sort of demigods. And this is simply not the case. We are fantastically complicated, fantastically intelligent, fantastically inventive animals. And we should keep that in mind.

Correspondent: Can words capture all the complexities of this Cartesian dilemma? This animal-human dilemma?

Banville: Words can only suggest. They can’t capture. You know, in a way, all writing is a kind of conjuring trick. You’re setting up a world that looks like, as I said earlier, feels like, tastes like the real world. But it’s not. So it’s all to do with suggestion. And of course the power of suggestion depends on the artistic gifts of the writer.

Correspondent: What about the potential for manipulating the reader? Is this something that you try to avoid? You would rather suggest than manipulate?

Banville: I have no sense of reader whatever. I write entirely for myself. Then when it’s finished, it becomes the reader’s. But when I’m doing it, it’s for me. And I believe the same is true of all writers, whatever they say. You cannot write with a reader in mind. Unless you’re writing a textbook or a completely formulaic crime novel or something. But if you’ve got any self-respect and you’re a real writer, you write for yourself. And then the miracle is that other people find in your work things that seem absolutely personal to them. Which is a very strange process.

The Bat Segundo Show #407: John Banville/Benjamin Black (Download MP3)