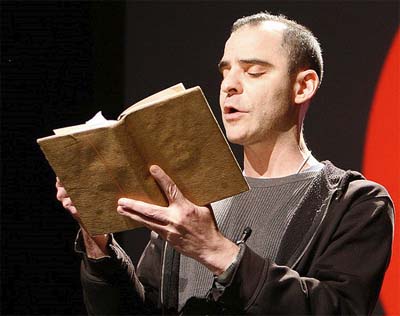

Paul Harding appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #364. He is most recently the author of Tinkers.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Tinging with Mingus and tinkering with Tinkers.

Author: Paul Harding

Subjects Discussed: [List forthcoming]

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: We were talking before all this about the idea of novels and whether or not they can actually serve as a handbook for life. Something I don’t necessarily believe in. And I don’t think you do. But I wanted to address that. Because your book, Tinkers, does, in fact, present life. And I’m wondering how you, as a writer or just in general, arrange text as a way to present life rather than dictate life. Was this ever a struggle for you when writing this?

Harding: Not with this. I think I had done my apprenticeship to bad prescriptive moralizing writing and just ended up writing very bad propaganda.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Harding: You know, it was just designed to show people how progressive and enlightened and intelligent I was. And then I’d say the kind of operative word is description. And precision of description. And if you describe things precisely, you end up bearing witness to the truth of your characters — in this case, characters’ lives — in a way that does them the kind of moral justice that’s misplaced when you think you’re going to moralize. For me, it even starts with the writing process. The difference between writing declarative prose and writing interrogative prose. Like I don’t presume that I know something and I’m going to tell you how it is and that afterwards, if you’re lucky, you’ll be as smart as me. What I do is that I try to write interrogatively, discover things, work through revelation. It’s just a type of aesthetic. But then what you leave on the page behind you — when the reader reads what you’ve written, the reader will have the same kind of revelations and moments of recognition. To me, that’s like the greatest experience as a reader. Those moments of recognition. Where you read something and you simultaneously realize, “I’ve always known that’s true. I’ve never thought about it consciously and I’ve never seen anybody put it into language before.” So there’s a kind of morality to that. There’s some sort of confirmation of common humanity or whatever. But it’s not prescriptive, small-minded minor kind of moralizing.

Correspondent: I’m very glad that you brought up description. Because one thing that I really think is interesting about this book is the hyperspecific nature of the description.

Harding: Right.

Correspondent: To offer an example, you have George “reading by the dim light of a small pewter lamp set on the rolltop desk at the far end of the couch.” Now that’s extremely specific. And I’m wondering if that serves as a way for you to get the reader inside George’s head. Or is this a way for you as a novelist to kind of know where everything is situated? The only person I think who writes that hyperspecifically is possibly William Gibson or someone like that. A lot of the 19th century authors do.

Harding: Yeah. And I’ve certainly spent all my reading time trolling around 19th and early 20th century fiction. I mean, I almost think of Thomas Mann’s little preface he has to The Magic Mountain. That we will be long on detail, but when was a book ever short on interest that was long on detail? People would argue against that novel’s glacial — but it’s sort of a bit of both. Which is while I’m writing, I’m blocking the scene out, you know? And since my characters in Tinkers — it’s so interior that I knew from the beginning that I had to keep the world embodied. I had to keep it physically, tangibly present. Because otherwise it would just be feasting on ether. So there’s that. There’s the kind of geography of the room. But then it’s also to make the reader feel like he or she has been put in a real place. Actually put in a place where there’s a chair to your left. There’s a certain physical feeling you get when you feel that there’s a chair to your left and a sofa over here and a painting over there. That sort of thing. I also just believe in the virtue of concrete nouns and verbs. And I think it’s true too that there ends up being something hyperreal, rather than surreal, about it. But there’s really a cool kind of bandwidth of unintended affects that you can’t predict. But you use that process of total precision, almost pointillist precision, that you end up getting into these kind of transcendent or metaphoric realms. But not by lifting up out of the world or evaporating off of it, but by going deeper into what’s imminent. So you’d get so materialistic about it that then it turns into something you don’t recognize and you sort of double back on yourself and it becomes unrecognizable and sort of unsettling and hyperreal. So I love that. I just love that phenomenon.

Correspondent: But it’s not just also in relation to materialism. It’s also in relation to place. Of course, the clock theme that goes throughout with The Reasonable Horologist, which I presume is invented.

Harding: Yeah, that’s all invented.

Correspondent: I’m wondering if that text within the text [The Reasonable Horologist] was included almost as a way to distract the reader from the fact that the text, the prose itself, is almost written in this kind of William James, 19th century mode. And that by having this, you can almost justify the style that you’re doing within the actual prose itself.

Harding: It’s a little bit of — on the most generic level, it’s just to change things up. It’s just to use relief. So much of the book is very somber and funereal and twilit. And this is just a little more verbose and florid, and kind of tongue-in-check. It’s kind of humorous. And so it keeps the textures changing. But, yeah, I think it’s also true. Because the writing is formal and that kind of precision leads to that kind of, “It sounds formal, so it sounds archaic to some extent.” It was also just a fun way to write in that kind of, “Welcome, dear reader, to Reason!” You know, it just worked emotionally with the character, with George the clock repairman. His upbringing was so chaotic and disorderly that the idea of the deterministic, mechanical view of the universe is appealing to him. The idea that you can fix things, that it’s mendable, and that there’s an order to everything.

The Bat Segundo Show #364: Paul Harding (Download MP3)

Rakoff: It means to either strengthen or weaken an argument. Which one does it mean?

Rakoff: It means to either strengthen or weaken an argument. Which one does it mean?