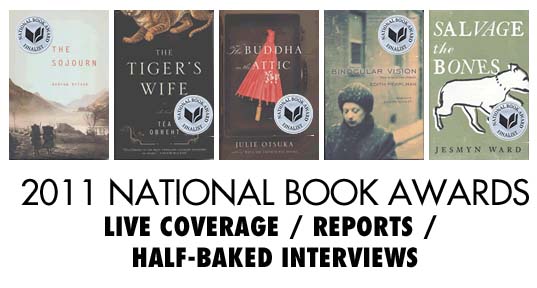

Téa Obreht appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #421. She is most recently the author of The Tiger’s Wife, winner of the Orange Prize and finalist for the National Book Awards (to be announced on Wednesday: check out Reluctant Habits and our Twitter feed for live coverage from the floor that evening).

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Pondering a future in which writers are trained by Carl Weathers.

Author: Téa Obreht

Subjects Discussed: Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger,” how much one needs to know about tigers, being a National Geographic nerd, research and laziness, readers who have different takes on a story, clumsiness, musicians who become butchers, precise metaphors within The Tiger’s Wife, having the illusion of knowing what you’re doing, talking in first person plural, storytelling and The Secret, regularly arriving at the wrong formula, the elephant scene, deathless men, finding inspiration at the Syracuse Zoo, why brains need to sit with ideas, working in a faux Balkans world, finding verisimilitude for faraway places within common present-day incidents, sharing earbuds on Walkmen and iPods, immediate points within life that connect you to stories, family members who avoid writers, writing what you know “at the moment,” trigger points, similarities between Underground and The Tiger’s Wife, Emir Kusturica, gypsy film soundtracks, learning English from Disney films, legends particular to Belgrade, the Kalemegdan fortress, film as a greater influence for dialogue than real life, Howard Hawks, bad cinematic trilogies, the Qatsi Trilogy, treating fiction as something fabricated, relationships between truth and fabrication, humor bridging the gap between magic and realism, laughing over awful events, Shoah, The Gulag Archipelago, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, The Master and Margarita, finding a humorous path to the real, Stewart O’Nan’s A Prayer for the Dying, bonding emotional with a book, whether death is inherently funny, Fawlty Towers, coffee grounds as personal mythology, thick Turkish coffee in the Balkans, parrots that quote poetry, legends that tend to spring up about English Bull Terriers in Belgrade, Kipling’s The Jungle Book vs. the 1967 Disney film, mythological animals, the rosy Disney view, reading from a non-American standpoint, being shocked by Kipling’s imperialism when discovered later in life, the dangers of embedded narrative, academics obliged to find silly interpretations in order to keep their jobs, mythology that is tied to a specific place, learning everything from Disney, American mythology, cowboy hats and immigrant stories, unnecessary suburban symbolism, hostile reviews from women, being confused as a YA novelist, paying attention to reviews, good art and polarizing people, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, critics who see things that the author never intended, standing by work, having doubts about early work, the inevitability of a few clunkers, deleting pages, overexposure and overexplaining, the possibility of Obreht turning into Smeagol if she wins the National Book Award, becoming corrupted by attention, J. Robert Lennon, insulating one’s self from attention, Sunset Boulevard, the importance of humility, defending the pursuit of writing and the need for books in a terrible economy, Richard Powers’s “What Does Fiction Know?”, the Occupy movements, and fiction as a form of help.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I must confess that Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger” was in my head on the way over here the entire time. And I have you to blame for that.

Obreht: (laughs) Thank you. I keep hearing it on radios now. Like whenever I do, I get embarrassed.

Correspondent: Really? You get embarrassed? You get shamed?

Obreht: I don’t know why. Because I get really into it. It’s pertinent now. And then I get embarrassed about myself.

Correspondent: Do you get sick of tigers now that you have dwelt upon them quite heavily and you have to constantly talk about them?

Obreht: You know, I don’t think I do. I think it’s just getting more and more entrenched into what I do every day. Every email I send has a tiger picture attached to it that’s pertinent to the conversation.

Correspondent: (laughs) Wow.

Obreht: I’m sure that at aome moment a big break will come and I’ll say, “I never want to see any feline again!” And I’ll kick cats as I go down the street. No, not really. Not really.

Correspondent: (laughs) Violence is welcome on this program.

Obreht: (laughs)

Correspondent: Even hypothetical violence. So you have to become a tiger expert, I presume? Have you been reading up on cats and the like?

Obreht: You know, I studied tigers a little bit for the writing of the book and went and sat in zoos a lot. And I’m a total National Geographic nerd anyway. So it came naturally.

Correspondent: Well, let’s talk about nerdom. National Geographic nerdom.

Obreht: Yay!

Correspondent: How much do you have to know about tigers to know about them? Or do they exist within the wonderful theater of the mind? What’s up?

Obreht: I’m a big believer in the theater of the mind. Especially when you’re dealing with fiction. I mean, there’s only so much you can know. And then there’s only so much of what you know that you can transmit before it begins to be clinical. So I think research, while it helps, can sometimes destroy you. And I was very happy to take a little bit of what I knew and run with that and let a thousand imaginations bloom about tigers.

Correspondent: Wow. So you’ve learned this fairly early on. A lot of writers have to wait decades before they realize sometimes, “You know, maybe I shouldn’t read every book on a subject.” You’ve actually managed to avoid that from the get-go. To what do you attribute this extra wisdom?

Obreht: Laziness. (laughs)

Correspondent: Laziness? Oh, I see. I see. Practical temperament concerns. (laughs)

Obrhet: No. I think I’m always terrified — I think a lot of students that I have had at Cornell have been terrified of not making their intentions known in their writing or not having something clear in their writing. I’ve always been terrified of the exact opposite. I’ve always been afraid of letting too much be known too quickly or hitting the reader over the head with something. Because I know that used to be one of my flaws. So I’m so overly cautious about it that I think that it sometimes cripples me. I think that there are some things that I could research a little more heavily or whatever I write about them.

Correspondent: Being too explicit about stuff. Like. Such as?

Obreht: Such as? I don’t know. I think that such as a particular kind of character interaction or…

Correspondent: Such as?

Obreht: Such as — well, actually I’m thinking about my short story — for some reason I can’t think of an example from the book, but my short story, “The Laugh” — there’s this tension between the two main characters. One is the husband of a recently deceased woman. And the other is his best friend, but also someone who was interested in the deceased wife. And I was terrified of laying this out too quickly and immediately and explicitly at the beginning of the story. Because it would totally break the tension. And so in an early — in the first five drafts of the story, it wasn’t clear at all. And people were like, “Why is this happening?” And I was like, “Well, he likes her! Or used to and now she’s dead.” So, for me, it’s always this holding back and then trying to ease into being okay with the information being there.

Correspondent: Is this one of the chief concerns when you’re going through this endless rewriting and endless revising? To find that tonal balance that really strikes between what the reader needs to know and what the reader needs to infer?

Obreht: Absolutely. And that’s one of the great endeavors of the short story — this negotiation between the reader and the writer and how that information is being transferred. And you can transfer information in a way where the reader knows. Like the implication is already there and all you have to do is trigger it with that one word for the reader’s neural pathways to open up in that particular direction. And it’s so much fun.

Correspondent: You sound like a drug dealer. Dopamine hits or something. (laughs)

Obreht: I do use a lot of caffeine! (laughs) But as a reader, I enjoy seeing how that happens. You know, how I came to the same conclusion as anther reader. That was one of the great exercises of workshop. How did you get to this place with this story? And I got to a completely different place? Or how did we arrive at the same place? Where was the information that led us both there? I love that as a reader. So I enjoy that as a writer as well.

Correspondent: But if you’re constantly revising to get that precision, how do you keep yourself in surprise? Because that, of course, is very important to maintain the life of a story.

Obreht: Oh, that just comes normally. Because I have no idea what I’m doing! (laughs)

Correspondent: Yeah. The big thing that nobody really understands. That writers really don’t know what they’re doing often.

Obreht: Yeah. Exactly. You know, you stumble into things. And you’ll be 75% of the way through something and suddenly it’s like, “Oh, I changed my mind! Actually, this is going to happen because it feels more normal, more natural.” Then you have to backtrack and shift everything. (flourishes with considerable exuberance, nearly knocking an object over)

Correspondent: (reflexes kicking in, saves object from falling off table) Almost knock things over.

Obreht: I’m gesticulating here!

Correspondent: No, no, no. If we knock something over, it will make this conversation 300% better.

Obreht: That’s awesome.

Correspondent: It’s already going very well.

The Bat Segundo Show #421: Téa Obreht (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced