(This is the second of a five-part roundtable discussion of Dana Spiotta’s Stone Arabia. Additionally, Spiotta will be in conversation with Edward Champion on July 20, 2011 at McNally Jackson, located at 52 Prince Street, New York, NY, to discuss the book further. If you’ve enjoyed The Bat Segundo Show in the past and the book intrigues you, you won’t want to miss this live discussion.)

Additional Installments: Part One, Part Three, Part Four, and Part Five

Darby Dixon writes:

A lot of interesting stuff so far. I’ll start off with my own opening thoughts — which pick up a few points from this discussion, I think — though there’s plenty more here for me to consider in more detail.

I’d like to start by looking at the book’s cover. Which — if this is in any way a novel about music or any sort of glory days in which the cover as a physical artifact actually means something — is hardly a bad place to start. But I find the cover of this book troubling for two particular reasons. Is the cover poorly executed? Or, more hopefully (and perhaps more likely), do these issues point to aspects or views of the book that I missed on my first reading?

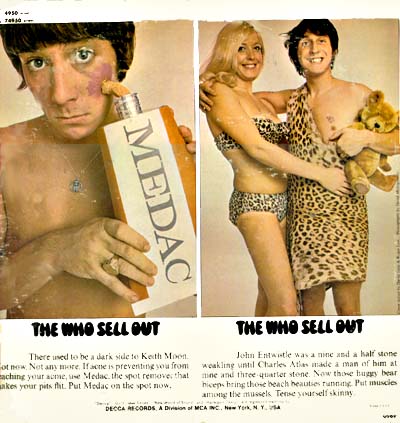

Consider the treatment of the title and the author type on the front cover. I’m not referring to the copyright mark placed after Spiotta’s name, a witty winking question mark that pays off with a dot-dot-dot-exclamation-point within the novel itself.* Rather I’m looking at the supposed handmade quality of the cover. If it is meant to allude to Nik’s self-made album art, why does it have to look so Photoshoppy? This cover never stank of real glue or caused any paper cuts. Why not?

What also bugs me — and you’ll have to see it by taking the dust jacket off your hardback copy and stretching it flat on the table in front of you — is that the background is mirrored from the front to the back. The distress along the top inside flaps is the tell. I can’t think of a good reason why it had to be this way.

Why then this postmodern take on the handmade? I ask because I did not read this book as a postmodern novel, although I guess there’s postmodernish stuff inside it. There’s some framing going on and a little bit of self-reference. But it felt well-contained to me; the effects are just means to an end. This is essentially representational work; neither Nik nor Denise feel like ciphers or “texts” to me, but, rather, realist characters with real issues drawn in a real manner: each drawing himself or herself into being. Maybe the mirrored back cover is a superfan-level Easter egg, a nod to whatever mirroring is happening between Nik and Denise. They are two creators, two storytellers: one far more gung-ho and self-assured than the other. But as I type that thought, my internal editor is all like, “Uh, really?” So.

Why then this postmodern take on the handmade? I ask because I did not read this book as a postmodern novel, although I guess there’s postmodernish stuff inside it. There’s some framing going on and a little bit of self-reference. But it felt well-contained to me; the effects are just means to an end. This is essentially representational work; neither Nik nor Denise feel like ciphers or “texts” to me, but, rather, realist characters with real issues drawn in a real manner: each drawing himself or herself into being. Maybe the mirrored back cover is a superfan-level Easter egg, a nod to whatever mirroring is happening between Nik and Denise. They are two creators, two storytellers: one far more gung-ho and self-assured than the other. But as I type that thought, my internal editor is all like, “Uh, really?” So.

So. Am I missing layers of irony and self-reference and other postmodern gobbledygook? Or do I have a legitimate desire for a cover that gets more real, more DIY? Is this a bit more of a scorched mess?**

Full disclosure: I came to this book (and this book discussion) a skeptic. I read Eat the Document because it sounded like the kind of book I was supposed to read. And, while I don’t remember hating it, I don’t remember loving it either. Stone Arabia mostly won me over though for various reasons. In time, I’ll get back around to Document and give it another shot (and pick up Lightning Field along the way). It didn’t hurt Arabia‘s case that my current reading project involves a stack of 1,000 page+ books. Being able to sit down and read Arabia over the course of a single weekend? Well, it read like an absolutely blissfully quick short story; so much so that, due to miscalculation on my part, I didn’t realize the ending was the ending until I turned the page and found no more story following it. (That ending. I’d like to swing back around to it in more depth later in this discussion, with anyone who is game.)

This book worked for me less as a novel about art and rock and success, and more for me as a novel about memory and time and how we use both to tell ourselves the stories of our own lives.*** Levi has offered quite a bit to chew on in this regard, and I’m still chewing on it myself. For me, what I think bumps the memory issue up on the queue is the fact that everything in the novel is filtered through Denise’s consciousness: either directly through her writing or indirectly through her point of view. She sees the kind of failing memory in her mother that might await her in later years, and it’s scared the wits out of her.**** She’s anticipating the downfall that awaits her and she’s struggling to arrest it before it can arrest her. In some way, she’s highly jealous of Nik’s apparent freedom from that; his ability to make his own story up has to be a severe kick in the sibling rivalry gut. But what can there be of it now? It’s funny how little left there is of their mom to approve or disapprove of the actions of either sibling. It’s a bit of a tragedy of impending morality. Denise and Ada also act a bit like Horatio to Nik’s Hamlet. If the journals and the albums are Nik’s heroic acts, the documentary and the Counterchronicles are their stories, at least the stories that people might actually get to hear.

This book worked for me less as a novel about art and rock and success, and more for me as a novel about memory and time and how we use both to tell ourselves the stories of our own lives.*** Levi has offered quite a bit to chew on in this regard, and I’m still chewing on it myself. For me, what I think bumps the memory issue up on the queue is the fact that everything in the novel is filtered through Denise’s consciousness: either directly through her writing or indirectly through her point of view. She sees the kind of failing memory in her mother that might await her in later years, and it’s scared the wits out of her.**** She’s anticipating the downfall that awaits her and she’s struggling to arrest it before it can arrest her. In some way, she’s highly jealous of Nik’s apparent freedom from that; his ability to make his own story up has to be a severe kick in the sibling rivalry gut. But what can there be of it now? It’s funny how little left there is of their mom to approve or disapprove of the actions of either sibling. It’s a bit of a tragedy of impending morality. Denise and Ada also act a bit like Horatio to Nik’s Hamlet. If the journals and the albums are Nik’s heroic acts, the documentary and the Counterchronicles are their stories, at least the stories that people might actually get to hear.

This is where all the Nik stuff comes into play for me. Where it really works is in its service to a story about memory, about making memory, and about making a story out of the life one is living. Is Nik a success? Neither commercial nor popular. Okay, is Nik a success as a brother? As a son? He seems too self-involved for that.***** No doubt this is a book as much about time as it is about memory, if indirectly. To pull off the projects that Nik pulls off; well, it requires massive amounts of time and effort and dedication. (A twenty album cycle! Not five, not ten. Twenty! You can’t do that while holding down a productive day job and taking care of your sick relative.) In this regard, he’s a success in a completely logical way. He did the things he set out to do. He succeeded, at whatever cost. He only needed a small handful of people to witness it, to make it real, and, even then, he never seemed especially interested in their actual reactions.****** In a day and age when fame and fortune appear right around the corner for everybody willing to fart out a lolcat-style meme, there’s something admirable about that. Is this a withdrawal from reality or a redefinition of reality? A determined, self-defined vision of reality? Could this book have been set in 2011 rather than 2004? Perhaps today, Nik’s “success” might feel all the more anachronistic. How much of this is happening right now that we don’t know about and aren’t supposed to know about?

In going on about Nik like that, I realize I’ve detracted a bit from my belief that Denise really is the emotional core of the book. She is, though, in some strange way, the character I felt myself most identifying with; or at least she’s the one I sorta rooted for. It’s something I’m trying to unpack for myself still; and for some reason I keep coming back to that crushing pile of debt she has been accumulating while taking care of her ailing brother******* and her ailing mother. You can’t buy memory, but having money on hand to try doesn’t hurt. More on this later in the discussion, I hope.

* — The whole author/artist-as-brand conversation is probably worth a couple thick discussion threads alone. I’ll admit that, as a current student in real art classes trying to make real art, I found the Thomas Kinkade stuff funny. Painter of Light, indeed. Paint this, Mr. Success Pants.

** — Is there a rock album cover that inspired this treatment that I’m not aware of? I’ll admit to missing vinyl the first time around due to youth, and, due to finances, neglecting the recent indie-hipster resurgence this time around. So my personal cover art experience is largely based on a 90’s and early 00’s CD collection. I know, I know. The big beautiful vinyl cover square is superior as a means of conveying the visual side of an album. But I think the folded up CD liner sheet gets (or got) a bit of a short shrift; how much earlier would I have hit the hay in high school if I’d been strictly focused on homework instead of occasionally pulling out one of those squares, unfolding it panel by panel to find the secrets contained within? How much has music’s impact on me been minimized by the lack of something, anything, physical to go with it? I, for one, miss accidentally cracking jewel cases. But I just can’t see finding time and cash enough to put a record player in anytime soon.

*** — Reading Nik as simply musician-creating-for-no-audience felt a bit “meh” to be, taken at face value. I mean, I’ve done the same thing, on a smaller scale; made stuff nobody’s listened to, I mean. It’s not that interesting a thing to me. Music is for ears! Music-as-music is better when other people hear it and like it. Or am I being overly simplistic (or obtuse?)

**** — Having seen some of those issues in the last decade in my own family has been similarly both terrifying and sobering. My dreams of my writing career eventually actually starting and lasting me well into late in a long, healthy, productive, and active mental life? I dunno. What will I think of this discussion fifty years from now? How shamed will I be in my distraction from blogging about the books I’ve been reading, from more actively keeping journals, from taking more pictures? What bundles will I leave behind that tell some small portion of my story, to whomever might be around to hear it?

***** — I’m not passing judgment there. I’d only be passing judgment on myself. I’ve got a lot of guilt bound up in my relationship to art, in the hours devoted to potentially fruitless pursuits that may have been better spent with loved ones or what others might call “doing good”: doing charity work or hopping a plane to a distant city to help someone other than myself. What good is that unpublished novel, or that self-portrait tucked away in a closet for the rest of my life? I can’t pass judgment on Nik because in some ways I wish I was him, the jerk.

****** — Oh, the crummy, crummy jerk.

******* — The selfish dick.

…and of course I realize immediately after I hit “send” at least one thing that I meant to (and forgot) to clarify: if I’m critical of that cover, I’m also so, so, so, so, so glad to see it was conceptually relevant to the contents of the book! This could have easily been yet another one of those blurry photos of a woman with her face turned away from the camera or cropped out of the frame. And maybe some flowers or something like that. Yawn. I praise the concept (and that red really is the right red, somehow, isn’t it? the kind of red you just want to curl up with in your hands while listening to it on a gigantic pair of headphones, no?) while raising an eyebrow at aspects of the execution. (I’ve had similar love/hate issues with the covers for Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, a book I badly need to reread, because, yeah, duh, there’s things to compare and contrast between these books; sadly I think the deck is stacked against me this next week. But, suffice it to say, I’m an self-acknowledged Egan fanboy, yes, and Spiotta, I think, is up to something else with her book. So it’s probably unfair of me to try to pick a book I prefer to another. If this was a Tournament of Books thing, I would politely and ethically rescind my position on the brackets. But! I’d very much like to see the two books sit down at the bar, grab some drinks, and talk shop. Is that what I’m saying? There’s enough bourbon here for both.)

Ahem. Carry on!

Robert Birnbaum writes:

I am struck by the realization that the more vocal of the aggregation who read on this planet expend a lot of verbiage and hand wringing about the prospects of books, literature, reading and what not. So it should not go unsaid that this opportunity for a diverse, spirited group of readers to commune is a joyful affirmation. So thanks for that, Ed Champion.

I am lucky to have, for the most part, the freedom to choose the books I want to read. While this is not a totally unblemished blessing, it is an immeasurably wonderful one. So the books that I pick up tend to reach my hands and eyes in almost infinitely (a large number) manifold ways. Dana Spiotta’s Stone Arabia came to me via Eddy’s latest literary initiative. But there is a context for reading this book — since, for me, reading takes place within my life and not as stepping out of it. If you know what I mean.

In the short period before picking up Spiotta’s tome, I had read two books — which pulled me in different, if not opposing directions. I picked up the ARC of Lydia Millet’s new opus, Ghost Lights, and delved in, propelled by the nimble and ironic prose. I found myself about two thirds of the way into this tale of a disenchanted IRS employee who embarks on a mission to Central America for his equally disenchanted wife. I was losing interest. But being close to the end, I finished the book. Besides a mildly surprising ending, I was not impressed or engaged.

In the meantime (or the same time), I had one of my periodic conversations with Jim Shepard, The Wizard of Williamstown). Part of our talk hit home immediately:

RB: I no longer feel compelled or obliged to finish books.

JS: Yeah, that’s really characteristic of a life spent reading. I am struck, when I talk to students or younger writers how much —- I guess I remember that feeling too —- how much they feel like, “No. If I got this far, in I want to say I did it [finished]?”

RB: There is always the occasional book that it takes longer to figure out.

JS: That’s the danger. If you bail too soon. I try to give books every possible reason to keep reading. But I don’t any longer feel bad about bailing. It’s not anger or contempt -— it’s “I think I get the idea here.”

In that same chat, Jim mentioned that he was reading and impressed by Bonnie Jo Campbell’s story collection, American Salvage. Which prompted me to pick up the copy of Campbell’s novel, the one that had been previously dispatched to some pile of miscellany.

Wow, this is a book that grabbed me from the first page. And though its resolution was profoundly satisfying, I was a little bereft to leave the lush and variegated world of riverfront Michigan.

So the next book I picked up was The Secret History of Costaguana by Colombian novelist Juan Gabriel Vasquez — mostly because I had tried to read his American debut, The Informers, with little pleasure. Another chance for Vasquez, and a trip to beleaguered Colombia with Joseph Conrad as a character, seemed enticing. And I was digging my way in when I received Stone Arabia and remembered my intention of participating in another Ed Champion extravaganza.

So the next book I picked up was The Secret History of Costaguana by Colombian novelist Juan Gabriel Vasquez — mostly because I had tried to read his American debut, The Informers, with little pleasure. Another chance for Vasquez, and a trip to beleaguered Colombia with Joseph Conrad as a character, seemed enticing. And I was digging my way in when I received Stone Arabia and remembered my intention of participating in another Ed Champion extravaganza.

So with no background (except some dust jacket info), I began to read. I reached Page 92, impressed by Spiotta’s precise and nimble prose but not engaged by the characters. Not unhappily, I had to put down the book to read Josh Ritter’s Bright’s Passage in preparation (such as it was) for my chat with Ritter (sweet and charming kid, by the way).

And then came Eddy’s first invitation (incitement?), which I may or may not have responded to with the clarity that I hope to exhibit in these later offerings. At that point, having read about half the book, I was clear that, had I not committed to joining a discussion, I would not have gone on reading Stone Arabia.

I don’t by any means see this as a negative assessment of the book. It wasn’t my kind of story. Plus, I already have to deal with the deaths of close friends, aging parents, and worries about losing my memory (and, ultimately, my mind) in real life. Plus the call of the unread always haunts me.

But then did I read the book in its entirety without other narratives impinging? As you can see, my thoughts so far about this book are so far mostly about my thoughts.

I see Part Two of this mission, where I now read what others have said and where I may arrive at something more objective (or less subjective) about Dana Spiotta’s book. That’s narcissism, isn’t it?

Bill Ryan writes:

I suppose, since everyone is pretty much throwing their own interpretive bowling balls in this opening frame, I’ll do the same. I’m going to fire off a half-cocked argument in which I can this very moment poke holes. And what fun is a discussion if someone can’t be completely wrong?

I’ll start off (with apologies) by disagreeing with Diane — I think Jay is slightly more than a fill-in. He’s the fuckable opposite of Nik. Denise and Jay deliberately ignore each other’s memories, and actively avoid discussing their histories. They prefer to live (cringe for cliche) “in the moment,” and seem to survive as a couple so long as they both agree to do as much. With Nik, there’s nothing but history, “shared knowing.” Jay teaches the next generation about art, Nik makes it for an audience of two or three. Jay brings her Kinkade’s schlock (seriously, take a look at Bambi’s First Year for a lurid example of Kinkade’s art) that “piles up in her garage.” Nik brings art that she treasures: a mere taste of the art that’s piling up in Nik’s garage. She fucks Jay (albeit lukewarmly), finances and forgives Nik, and ultimately carries his torch. We get no news of poor balding Jay and his “off-putting, almost creepy” sweaters.

I think here we get Denise’s answer to Sarah’s question about the value of art, purity, etc.: Thomas Kinkade’s “art” vs. Nik Worth’s music and Chronicles.

I think here we get Denise’s answer to Sarah’s question about the value of art, purity, etc.: Thomas Kinkade’s “art” vs. Nik Worth’s music and Chronicles.

The only thing that Denise really appreciates is Nik’s art, and seeing him carry that art to its conclusion was Denise’s self-imposed destiny. Nik “is” his art, for better or worse. Denise is his art’s audience. Just as it’d be unthinkable for me to tell Richard Serra what shape his next giant metal sculpture should take, Denise ultimately can’t stop Nik from following through with his art.

Denise admits that she’s complicit in Nik’s downfall. She is, if not pushing, then enabling Nik towards whatever end he comes to at the end of the book. Her need to write her own history of the events preceding “the crisis” meant to read as a pardon for her part in Nik’s death. Like Sarah mentioned, she’s rewriting family history in the Counterchronicles to fit the history she needs to forgive herself for Nik’s apparent suicide. An alibi.

That might also explain her need to get it all down, beyond just her failing memory. Even when she should “call someone” when she’s almost certain her brother’s killed himself. She has to write, she has to formulate a reality in which she isn’t a complete failure. Her brother’s sarcastic note about her being a “writer, now” could also be read as a grim prediction and condemnation of her rewriting history.

Throwing on my pop psychology hat now, Denise can’t stop him because she’s afraid to upset whatever mixture of drugs, alcohol, and psyche come together to create the art she alone can appreciate so well. Nik’s “concessions,” his need to “get off his face, out of his head, expand, shut down, alter, spin, fly, sleep, wake up, float” was there as long as Denise could remember.

Denise has her own “concession.” Nik, his music, his art, his life, is her life’s concession. If everyone lives with these consolations, and if the non-stop dissociative drugging was Nik’s consolation, Denise was willing to accept those terms so long as she could feel the “consolation of recognition” that she felt in Nik’s art. Because Denise is ultimately empty. She fills herself with whatever she can — she regularly “possesses” these “permeable moments” that wrack her with guilt and empathy. Again, I read these moments as further attempts to convince her audience (us? herself? Ada?) that we should forgive her, the patron saint of lost musicians. She’s so useless that she ends up crying on the doorstep of the woman she’d flown cross-country and driven hundreds of miles to “help.” How could she help Nik?

Finally, when Nik’s gone, Denise becomes the de facto arbiter of Nik and his art. Now, rather than just his audience, she’s his curator. “It’s hard to believe [Nik and his art] is really gone,” Denise says. “But there is this.”

“What remains,” says Ada.

“And what I remember, of course.”

I’d be hard pressed to think of a more dismal life than correcting YouTube commentators, but this is what Denise is finally left with. Maybe it’s enough, negotiating the Chronicles and Counterchronicles. It sounds like a sad fate to me.

Roxane Gay writes:

I’ve enjoyed the conversation thus far. I’ll just ramble through some thoughts on this book

I’m not familiar with Spiotta. So I did not know what to expect from this book. But I found it very timely. I read Nik as a blogger before there was blogging. The Internet makes it very easy for artists and writers and musicians, and even people who are none of these things, to chronicle their careers or lives obsessively — whether those careers or lives are real or imagined, interesting or quotidian. It was interesting that Ada actually was a blogger and Denise stayed apprised of her daughter’s interior life via blog, while staying apprised of her brother’s interior life through the Chronicles, or his retro blog. Nik and his imaginary life, the Chronicles, blogging, social networking, sharing what we’re watching on Twitter — all these things speak to Sontag’s thoughts on living as having one’s life recorded. And this, along with the idea that we are not truly alive and can’t be remembered if we do not leave artifacts behind documenting that we were, indeed, here. Documenting our lives also connects to memory which was such a dominant theme in this book. Denise became the documentarian of many lives — her own, her mother and brother’s lives, sometimes her daughter’s life, sometimes the lives of strangers in how she followed the news. At times, I felt like she saw her responsibility as bearing witness.

I don’t know if Nik is an artist, but he certainly performs the part of the artist very well. I was fascinated by the sheer extent of how he chronicled his imaginary career and the obsessive attention to detail, and how Spiotta was able to convey the obsession so convincingly. I would not say Nik is an impostor as much as he is a coward. He believes in his art enough to make it, but he doesn’t believe in his art enough to push it beyond the claustrophobic community he has created himself — people who, for the most part, have a certain obligation to love and appreciate his art. I thought of Hoarders, which airs on A&E, as I read this book. The show follows people who hoard trash, dolls, beer cans, and other strange ephemera that holds some deep emotional significance, even as it threatens to drive these people from their very homes. I read Nik as hoarding this chronicle of his imaginary life, slavishly devoted to the upkeep of that imaginary life even in the face of what would be deemed, by many, as abject failure.

I don’t know if Nik is an artist, but he certainly performs the part of the artist very well. I was fascinated by the sheer extent of how he chronicled his imaginary career and the obsessive attention to detail, and how Spiotta was able to convey the obsession so convincingly. I would not say Nik is an impostor as much as he is a coward. He believes in his art enough to make it, but he doesn’t believe in his art enough to push it beyond the claustrophobic community he has created himself — people who, for the most part, have a certain obligation to love and appreciate his art. I thought of Hoarders, which airs on A&E, as I read this book. The show follows people who hoard trash, dolls, beer cans, and other strange ephemera that holds some deep emotional significance, even as it threatens to drive these people from their very homes. I read Nik as hoarding this chronicle of his imaginary life, slavishly devoted to the upkeep of that imaginary life even in the face of what would be deemed, by many, as abject failure.

Edward asks what our judgments are worth when so many people are providing their own commentary and it is a good question: one that people in many fields are asking. Social media, the Internet, and what have you have made it possible for everyone to be a critic. So we have to ponder the value of criticism when it has been diluted the way it has in recent years. Nik himself proves that everyone’s a critic when he solipsistically reviews his own albums. He certainly takes that solipsism to a new level by sometimes critiquing himself negatively, but I find his project to be the ultimate expression of this notion of anarchic, overly democratic criticism — both creating art and then providing commentary on that very same art. Who does that? If a self-published writer (who is already pretty marginalized in the publishing world) were to then review her own work, the response would be swift and merciless. There’s a real tenderness, though, in how the people in Nik’s life view his Chronicles and self-criticism. It would be easy to think of Nik as a deluded, obsessive genius or impostor or coward but there’s also more to him. He demonstrates a real awareness, for example, when he articulates that he knows precisely the slant Ada will take in her documentary. He knows how he appears but remains undeterred. There’s something to that.

I would have loved to see more done with the design of this book. I kept wanting to see more evidence of the Chronicles other than the brief glimpses we were given. There was a real opportunity here to do something conceptually interesting and that opportunity was missed.

Here we have Nik, a musician who has devoted decades of his life (1970s-2003, a time period that intriguingly matches how long it took Brian Wilson to get around to

Here we have Nik, a musician who has devoted decades of his life (1970s-2003, a time period that intriguingly matches how long it took Brian Wilson to get around to  Would we be more satisfied accepting art on its own emotional terms? That’s a big question too. Because just look at the serious grief Denise offers in response to the news cycle, the ostensible “reality” that she feels compelled to confront. She can’t even name Lynndie England as she takes in the Abu Ghraib photos, but, much as many (including Nik) speculate on Nik’s character, she finds herself fixating on England’s “storm chasing,” even after Denise confesses that she “eluded any explanations.” Perhaps this is the ultimate response to Debuffet. And if we want to bring up

Would we be more satisfied accepting art on its own emotional terms? That’s a big question too. Because just look at the serious grief Denise offers in response to the news cycle, the ostensible “reality” that she feels compelled to confront. She can’t even name Lynndie England as she takes in the Abu Ghraib photos, but, much as many (including Nik) speculate on Nik’s character, she finds herself fixating on England’s “storm chasing,” even after Denise confesses that she “eluded any explanations.” Perhaps this is the ultimate response to Debuffet. And if we want to bring up  First is the idea of audience, and even that idea, as filtered through Spiotta’s novel, goes off in a number of different directions. There’s young Nik playing and posing to his girlfriend Lisa and Denise, the image Spiotta returns to in a big way at the end of the book (and which led me to a particular conclusion about the book that I’ll get to in a bit). Obviously, there is Nik’s choice to conduct his massive project more or less privately, with Denise as his primary audience, commentator and admirer. There’s Ada and her documentary, wishing to bring her uncle into the light of a greater audience. All have intentions, noble and selfish, thoughtful and venal – and that’s one of the many things that so impressed me about Stone Arabia, which is that it tackles the notion of whether the expression of art is “purer” with a tiny audience while also subverting it. Does art function in a vacuum? Is “selling out” a less worthy or more worthy goal? Spiotta simply presents possibilities here, but it’s up to us, as readers, to come to our own judgments, and then, in reaching them, get hoisted by our own petard because we sought some element of rightness or wrongness here.

First is the idea of audience, and even that idea, as filtered through Spiotta’s novel, goes off in a number of different directions. There’s young Nik playing and posing to his girlfriend Lisa and Denise, the image Spiotta returns to in a big way at the end of the book (and which led me to a particular conclusion about the book that I’ll get to in a bit). Obviously, there is Nik’s choice to conduct his massive project more or less privately, with Denise as his primary audience, commentator and admirer. There’s Ada and her documentary, wishing to bring her uncle into the light of a greater audience. All have intentions, noble and selfish, thoughtful and venal – and that’s one of the many things that so impressed me about Stone Arabia, which is that it tackles the notion of whether the expression of art is “purer” with a tiny audience while also subverting it. Does art function in a vacuum? Is “selling out” a less worthy or more worthy goal? Spiotta simply presents possibilities here, but it’s up to us, as readers, to come to our own judgments, and then, in reaching them, get hoisted by our own petard because we sought some element of rightness or wrongness here. I think Ed and Sarah have done a better job than me of analyzing the many connections in the novel — I didn’t think about Brian Wilson, though I did think of Spiotta’s great Eat The Document often while reading Stone Arabia — but I did form one strong impression that neither Ed nor Sarah focused on. To me, it’s obvious that this is a book about memory. There are five characters in the book: Denise, Nik, their mother, Jay the boyfriend, and Ada. They form a pentagon of attitudes about memory.

I think Ed and Sarah have done a better job than me of analyzing the many connections in the novel — I didn’t think about Brian Wilson, though I did think of Spiotta’s great Eat The Document often while reading Stone Arabia — but I did form one strong impression that neither Ed nor Sarah focused on. To me, it’s obvious that this is a book about memory. There are five characters in the book: Denise, Nik, their mother, Jay the boyfriend, and Ada. They form a pentagon of attitudes about memory. As for Jay, he seemed to me an aside. His twee obsession with Thomas Kinkade kitsch and lukewarm kindness means Jay lacks the capacity to harm Denise. He’s a warm body. Given that all of Denise’s energies are tied up in Nik and her mother (Ada is independent enough that Denise arguably needs Ada more than Ada needs her), she hasn’t room or inclination for anything more in her life.

As for Jay, he seemed to me an aside. His twee obsession with Thomas Kinkade kitsch and lukewarm kindness means Jay lacks the capacity to harm Denise. He’s a warm body. Given that all of Denise’s energies are tied up in Nik and her mother (Ada is independent enough that Denise arguably needs Ada more than Ada needs her), she hasn’t room or inclination for anything more in her life.