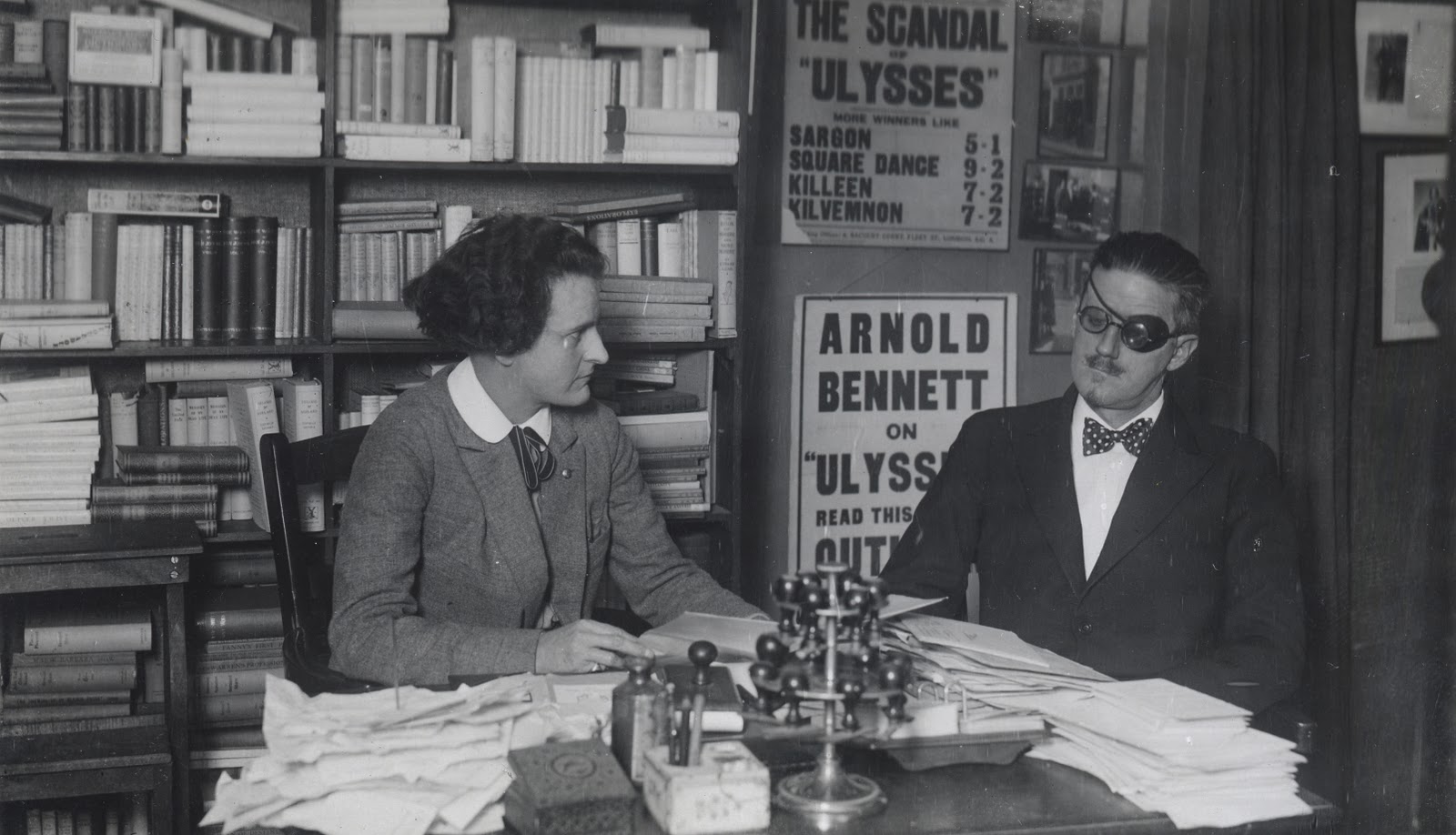

It is quite possible that I sacrificed some of my best reading hours in 2013 wading through anything written by or having to do with James Joyce: all part of my slow yet methodical efforts to advance behind #77 in the Modern Library Reading Challenge.* I’ve been working on Joyce since November 20, 2012. It’s a healthy relationship. He cooks dinner. I wash the dishes. On pleasant days, we go for long walks together. Sometimes, we even cuddle. Reading Finnegans Wake at a near glacial pace has forced me to revisit Dubliners, Portrait, and Ulysses, which has summoned Richard Ellmann, Gordon Bowker, and Homer from the stacks and Frank Delaney through the earbuds. I have looked up endless esoteric references. I have met with Joyce acolytes in secret dens. I have spent many late nights contemplating everything from Vico’s New Science to back issues of Tit-Bits published around 1904. All this will be written about in depth — hopefully sometime in 2014, when I reach the mighty “A way a lone a last a loved a long the” wending its cyclical posterior back to “riverrun.”

Despite all this, I did manage to read 125 books in 2013. The fifteen titles below all popped out like scandalous performers exploding from a giant birthday cake. I also started Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, a wise and breathtaking autobiographical novel that chronicles the pains and pleasures of existence. I didn’t include My Struggle on my list because, as marvelous as it is, I really need to see how it ends. (There are six volumes in total. Only the first two have been translated into English, with the third due in May.) But I am fairly certain that Knausgaard will make the cut in the future, once the extraordinarily capable Don Bartlett concludes his fine translation work on this quite important contribution to literature.

Here are my fifteen favorite books from 2013, in alphabetical order. I was able to interview many of these writers for The Bat Segundo Show and Follow Your Ears and have provided links to the shows.

Matt Bell, In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods: It remains my belief that bears are among the most underrated animals in fiction. Not enough novelists use them. When bears do show up in narratives, they are often found in trite poems written by addled hipsters who are more concerned with courting shallow attention than writing real literature. Bell’s debut novel not only contains a bear. It includes a whole universe of squids and “fingerlings” that could be fabulist creations or could originate from intricate grief. It uses minimalist designators (“the husband,” “the wife,” “the fingerling,” a fixed location seemingly in the middle of nowhere) to grow a maximalist universe, with endless rooms in the titular house propagating in direct proportion with complicated feelings. Language itself obscures and deepens seemingly simplistic sentiments. (It wasn’t a surprise to see the unadventurous reactionaries at the New York Times Book Review willfully misunderstand that last flourish, not kenning how Bell’s repetition and emphasis on physicality could be part of the puzzle.) After one too many wretched novels written by loathsome subjects of vapid Thought Catalog essays, it turned out that Bell’s book was the surreal corrective we needed all along. (Bat Segundo interview, 62 minutes)

Matt Bell, In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods: It remains my belief that bears are among the most underrated animals in fiction. Not enough novelists use them. When bears do show up in narratives, they are often found in trite poems written by addled hipsters who are more concerned with courting shallow attention than writing real literature. Bell’s debut novel not only contains a bear. It includes a whole universe of squids and “fingerlings” that could be fabulist creations or could originate from intricate grief. It uses minimalist designators (“the husband,” “the wife,” “the fingerling,” a fixed location seemingly in the middle of nowhere) to grow a maximalist universe, with endless rooms in the titular house propagating in direct proportion with complicated feelings. Language itself obscures and deepens seemingly simplistic sentiments. (It wasn’t a surprise to see the unadventurous reactionaries at the New York Times Book Review willfully misunderstand that last flourish, not kenning how Bell’s repetition and emphasis on physicality could be part of the puzzle.) After one too many wretched novels written by loathsome subjects of vapid Thought Catalog essays, it turned out that Bell’s book was the surreal corrective we needed all along. (Bat Segundo interview, 62 minutes)

Eleanor Catton, The Luminaries: What if you designed a 900 page novel around the dichotomy paradox, where each section was half the length of the previous section? What if you also attempted to work in the golden ratio? And just for the hell of it, what if you decided to set the action in 1865 and 1866, aligning the temperament of twelve characters to astrology? But let’s not stop there. What if you also injected this novel with slyly accurate historical detail and a shifting relationship between what is articulated to the reader and what is not? You’d have Eleanor Catton’s extraordinary second novel, which has been wrongfully trivialized in America as a mere Dickens pastiche. I’m sure that if you’re a joyless illiterate dope like Janet Maslin, this probably is a “critic’s nightmare.” But here’s the truth: I have not read a contemporary novel that has so adroitly manipulated massive strands of storytelling with an ambitious thematic structure since David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas. There is much in this great book to chew on: what we know about people through facts and gossip, how wealth becomes fluid through avarice and want. Even the way in which narrative information is conveyed and reader assumptions is skillfully challenged, forming almost an alternative astrology beneath the apparent astrological structure. Catton is a novelist of the first rank. She absolutely deserved the Booker for this. And I urge all interested parties to read this massive novel when they have the chance. (Bat Segundo interview, 71 minutes)

Eleanor Catton, The Luminaries: What if you designed a 900 page novel around the dichotomy paradox, where each section was half the length of the previous section? What if you also attempted to work in the golden ratio? And just for the hell of it, what if you decided to set the action in 1865 and 1866, aligning the temperament of twelve characters to astrology? But let’s not stop there. What if you also injected this novel with slyly accurate historical detail and a shifting relationship between what is articulated to the reader and what is not? You’d have Eleanor Catton’s extraordinary second novel, which has been wrongfully trivialized in America as a mere Dickens pastiche. I’m sure that if you’re a joyless illiterate dope like Janet Maslin, this probably is a “critic’s nightmare.” But here’s the truth: I have not read a contemporary novel that has so adroitly manipulated massive strands of storytelling with an ambitious thematic structure since David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas. There is much in this great book to chew on: what we know about people through facts and gossip, how wealth becomes fluid through avarice and want. Even the way in which narrative information is conveyed and reader assumptions is skillfully challenged, forming almost an alternative astrology beneath the apparent astrological structure. Catton is a novelist of the first rank. She absolutely deserved the Booker for this. And I urge all interested parties to read this massive novel when they have the chance. (Bat Segundo interview, 71 minutes)

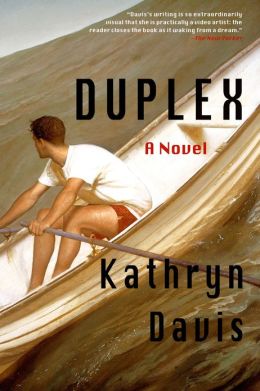

Kathryn Davis, Duplex: I must confess that I have a slight prejudice against novels that go out of their way to destroy the underlying structure every other chapter. Yet it is to Davis’s tremendous credit that I was not only won over by her remarkably inventive and deeply emotional novel, but that I found myself urging strangers in bookstores to buy it. This novel, with its robots, dogs, sorcerers, outlandish suburbs, tsunamis, and rabbits, is almost impossible to describe. But it offers its own unusual argument for the promising anarchism of life. When we stick to our conclusive guns, what do we give up in knowing people? Are there indeed duplexes we will discover when we’re not looking? I found myself greatly enjoying the fluidity of Davis’s universe, in part because of the novel’s descriptive precision (“The Woodard Estate used to be a brilliant jewel on the brow of the third of the three little green hills you come to upon leaving the schoolyard, after passing the water tower and crossing the old railroad bridge.”). You may very well enjoy meticulous geography as you experience it, but Davis’s provocative question involves knowing how to survive when it disappears tomorrow. (Bat Segundo interview, 62 minutes)

Kathryn Davis, Duplex: I must confess that I have a slight prejudice against novels that go out of their way to destroy the underlying structure every other chapter. Yet it is to Davis’s tremendous credit that I was not only won over by her remarkably inventive and deeply emotional novel, but that I found myself urging strangers in bookstores to buy it. This novel, with its robots, dogs, sorcerers, outlandish suburbs, tsunamis, and rabbits, is almost impossible to describe. But it offers its own unusual argument for the promising anarchism of life. When we stick to our conclusive guns, what do we give up in knowing people? Are there indeed duplexes we will discover when we’re not looking? I found myself greatly enjoying the fluidity of Davis’s universe, in part because of the novel’s descriptive precision (“The Woodard Estate used to be a brilliant jewel on the brow of the third of the three little green hills you come to upon leaving the schoolyard, after passing the water tower and crossing the old railroad bridge.”). You may very well enjoy meticulous geography as you experience it, but Davis’s provocative question involves knowing how to survive when it disappears tomorrow. (Bat Segundo interview, 62 minutes)

Elliott Holt, You Are One of Them: It’s fascinating to me that two coruscating works of art in 2013 — Elliott Holt’s debut novel and the wonderful television series, The Americans — have involved revisiting the end of the Cold War. There’s a part of me that would like to think that the artists in question were preparing themselves for Edward Snowden’s extremely disturbing revelations about our surveillance state. But exploring defection, in both cases, reveals that pivotal tie between loyalty and memory. You Are One of Them starts with the most seemingly innocuous of premises: idealistic letters sent by two schoolgirls to Premier Andropov beseeching peace. One of the sisters gets an answer and a Samantha Smith-style invitation to visit the Soviet Union. Fame follows. So does death. Or does it? Years later, Sarah Zuckerman (the other schoolgirl) takes a trip to Russia. And her journey, intermingled with such exacting details expat nightclubs in Moscow, the Russian advertising world, and American cleanliness, is a painful unveiling of how to contend with the lies and deceits of other people as an adult while holding onto your dignity. (Bat Segundo interview, 65 minutes)

Elliott Holt, You Are One of Them: It’s fascinating to me that two coruscating works of art in 2013 — Elliott Holt’s debut novel and the wonderful television series, The Americans — have involved revisiting the end of the Cold War. There’s a part of me that would like to think that the artists in question were preparing themselves for Edward Snowden’s extremely disturbing revelations about our surveillance state. But exploring defection, in both cases, reveals that pivotal tie between loyalty and memory. You Are One of Them starts with the most seemingly innocuous of premises: idealistic letters sent by two schoolgirls to Premier Andropov beseeching peace. One of the sisters gets an answer and a Samantha Smith-style invitation to visit the Soviet Union. Fame follows. So does death. Or does it? Years later, Sarah Zuckerman (the other schoolgirl) takes a trip to Russia. And her journey, intermingled with such exacting details expat nightclubs in Moscow, the Russian advertising world, and American cleanliness, is a painful unveiling of how to contend with the lies and deceits of other people as an adult while holding onto your dignity. (Bat Segundo interview, 65 minutes)

Kiese Laymon, Long Division: While other writers squandered the sad scraps of their waning talent with inane books about zombies and poker, beckoning empty nostalgic calories to fulfill a book contract, Kiese Laymon — much like James McBride and Mitchell S. Jackson — had the vivacity and the stones to explore the uncomfortable truths about what it means to live in America, specifically Mississippi, through genre’s empowering possibilities. Long Division is a bold time-traveling saga unafraid to take risks, recalling the biting ire of a young Percival Everett. It includes daring comparisons between slavery and the Holocaust. It’s one of the few novels I read this year exploring how a community survives on throwaway book culture (“the Bible was better than those other spinach-colored Classic books that spent most of their time flossing with long sentences about pastures and fake sunsets and white dudes named Spence”), even as it stares down the influence of viral videos, teenage sex, and celebrity. In offering two versions of a 14-year-old boy named City Coldson, one in 1985 and one in 2013, Laymon confronts how black identity remains rooted in fragmentation, what he has identified in a separate essay as “the worst of white folks.” Long Division‘s original corporate publisher was too afraid to put out this book. Fortunately, the good folks at Agate Publishing allowed Kiese to be Kiese. Let us hope that more important voices like Laymons’s are allowed to storm the gates in 2014. (Bat Segundo interview, 54 minutes)

Kiese Laymon, Long Division: While other writers squandered the sad scraps of their waning talent with inane books about zombies and poker, beckoning empty nostalgic calories to fulfill a book contract, Kiese Laymon — much like James McBride and Mitchell S. Jackson — had the vivacity and the stones to explore the uncomfortable truths about what it means to live in America, specifically Mississippi, through genre’s empowering possibilities. Long Division is a bold time-traveling saga unafraid to take risks, recalling the biting ire of a young Percival Everett. It includes daring comparisons between slavery and the Holocaust. It’s one of the few novels I read this year exploring how a community survives on throwaway book culture (“the Bible was better than those other spinach-colored Classic books that spent most of their time flossing with long sentences about pastures and fake sunsets and white dudes named Spence”), even as it stares down the influence of viral videos, teenage sex, and celebrity. In offering two versions of a 14-year-old boy named City Coldson, one in 1985 and one in 2013, Laymon confronts how black identity remains rooted in fragmentation, what he has identified in a separate essay as “the worst of white folks.” Long Division‘s original corporate publisher was too afraid to put out this book. Fortunately, the good folks at Agate Publishing allowed Kiese to be Kiese. Let us hope that more important voices like Laymons’s are allowed to storm the gates in 2014. (Bat Segundo interview, 54 minutes)

J. Michael Lennon, Norman Mailer: A Double Life: It’s easy to dog on Norman Mailer. He stabbed his second wife Adele and didn’t suffer any consequences. He helped to get Jack Henry Abbott released from prison, only to see Abbott stab a waiter to death as he was loose on the streets. He stood against women’s liberation. There is an undeniably savage quality to Mailer as a writer and Mailer as a man. Indeed, I penned a vituperative obituary not long after Mailer kicked the bucket. (I had not read The Armies of the Night, arguably a Mailer masterpiece, at the time.) Lennon’s biography does a remarkable job at getting 21st century readers to understand that there was more to Mailer than his sins would lead us to believe. Lennon doesn’t flinch from many of Mailer’s indiscretions, nor is he diffident in pointing out just how crazy some of his arguments were. This biography makes such a persuasive case for Mailer that it actually compelled me to read all of Mind of an Outlaw (a big, carefully edited essay collection released by Random House this year), as well as other Mailer books. It turns out that Mailer’s spirit is strangely inspiring amid the turmoil of today. And one comes away from this book wondering whether any talent close to Mailer could flourish in today’s atmosphere of instant digital gratification. Perhaps within Mailer’s double life are some kernels of tomorrow’s possibilities. (Bat Segundo interview, 63 minutes)

J. Michael Lennon, Norman Mailer: A Double Life: It’s easy to dog on Norman Mailer. He stabbed his second wife Adele and didn’t suffer any consequences. He helped to get Jack Henry Abbott released from prison, only to see Abbott stab a waiter to death as he was loose on the streets. He stood against women’s liberation. There is an undeniably savage quality to Mailer as a writer and Mailer as a man. Indeed, I penned a vituperative obituary not long after Mailer kicked the bucket. (I had not read The Armies of the Night, arguably a Mailer masterpiece, at the time.) Lennon’s biography does a remarkable job at getting 21st century readers to understand that there was more to Mailer than his sins would lead us to believe. Lennon doesn’t flinch from many of Mailer’s indiscretions, nor is he diffident in pointing out just how crazy some of his arguments were. This biography makes such a persuasive case for Mailer that it actually compelled me to read all of Mind of an Outlaw (a big, carefully edited essay collection released by Random House this year), as well as other Mailer books. It turns out that Mailer’s spirit is strangely inspiring amid the turmoil of today. And one comes away from this book wondering whether any talent close to Mailer could flourish in today’s atmosphere of instant digital gratification. Perhaps within Mailer’s double life are some kernels of tomorrow’s possibilities. (Bat Segundo interview, 63 minutes)

Claire Messud, The Woman Upstairs: “How angry am I? You don’t want to know. Nobody wants to know about that.” So begins The Woman Upstairs. Nora Eldridge, the self-proclaimed “good girl” who narrates Messud’s latest novel, has the kind of anger that seethes just underneath the surface of American life, but that is rarely voiced in fiction and in public debate: in part because Nora is a woman and in part because she thinks and feels in ways we’re not expected to express anymore. Of course, none of these prohibitions stops Nora. As Nora tells us more about her life, we begin to wonder just how responsible she is for the place she’s in. Does cruelty from others beget more cruelty? Or are we all the victims of, quite literally, naked opportunism? Many literary tastemakers leaned toward Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers, which was a laudable portrait of 1970s radicalism. But, for me, Messud’s was the more slyly political and visceral novel. In an age where people are more determined to hide how they really feel, what’s more subversive than telling someone what’s really on your mind? (Bat Segundo interview, 51 minutes)

Claire Messud, The Woman Upstairs: “How angry am I? You don’t want to know. Nobody wants to know about that.” So begins The Woman Upstairs. Nora Eldridge, the self-proclaimed “good girl” who narrates Messud’s latest novel, has the kind of anger that seethes just underneath the surface of American life, but that is rarely voiced in fiction and in public debate: in part because Nora is a woman and in part because she thinks and feels in ways we’re not expected to express anymore. Of course, none of these prohibitions stops Nora. As Nora tells us more about her life, we begin to wonder just how responsible she is for the place she’s in. Does cruelty from others beget more cruelty? Or are we all the victims of, quite literally, naked opportunism? Many literary tastemakers leaned toward Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers, which was a laudable portrait of 1970s radicalism. But, for me, Messud’s was the more slyly political and visceral novel. In an age where people are more determined to hide how they really feel, what’s more subversive than telling someone what’s really on your mind? (Bat Segundo interview, 51 minutes)

Alissa Nutting, Tampa: So Nutting’s controversial novel about a Florida middle-school teacher named Celeste Price who seduces and sexually abuses her students makes you uncomfortable? Cry me a fucking river. Life is uncomfortable. Like all great art, Tampa enters into dangerous territory. But it is brave, vivacious, and it has the courage to pursue its subject with a sense of humor. The people who have condemned this book have done so without actually engaging with the text. Earlier this year, at the Strand Bookstore, I observed an obnoxious and humorless freelance book critic, someone who has been published in several outlets, speak very loudly about how she couldn’t be bothered to make it past Page 50 because she was so offended by the book. She derided Tampa in the strongest possible terms, even though she had never finished it. I also got into an online argument with some illiterate nitwit who writes for Book Riot because she too had condemned the book as “unbelievable” even though she couldn’t cite a specific example when I challenged her. If you feel the need to condemn a book and you can cannot be bothered to read it or cite it, then you don’t have the right to venture an opinion. You are lazy, ignorant, and uninformed. No better than some Tea Party type holding the government hostage. More importantly, you’re missing out on one of the best books of 2013. (Bat Segundo interview, 75 minutes)

Alissa Nutting, Tampa: So Nutting’s controversial novel about a Florida middle-school teacher named Celeste Price who seduces and sexually abuses her students makes you uncomfortable? Cry me a fucking river. Life is uncomfortable. Like all great art, Tampa enters into dangerous territory. But it is brave, vivacious, and it has the courage to pursue its subject with a sense of humor. The people who have condemned this book have done so without actually engaging with the text. Earlier this year, at the Strand Bookstore, I observed an obnoxious and humorless freelance book critic, someone who has been published in several outlets, speak very loudly about how she couldn’t be bothered to make it past Page 50 because she was so offended by the book. She derided Tampa in the strongest possible terms, even though she had never finished it. I also got into an online argument with some illiterate nitwit who writes for Book Riot because she too had condemned the book as “unbelievable” even though she couldn’t cite a specific example when I challenged her. If you feel the need to condemn a book and you can cannot be bothered to read it or cite it, then you don’t have the right to venture an opinion. You are lazy, ignorant, and uninformed. No better than some Tea Party type holding the government hostage. More importantly, you’re missing out on one of the best books of 2013. (Bat Segundo interview, 75 minutes)

Thomas Pynchon, Bleeding Edge: Several reviewers were needlessly hostile to Pynchon’s latest volume, blaming the famous recluse for not delivering another Gravity’s Rainbow. But Bleeding Edge is not only a very funny book stacked to the nines with references (meticulously documented by the good folks at Pynchon Wiki). It’s a loving and sometimes irreverent portrait of the end of the 20th century and perhaps the end of America’s soul, reading at times like a call and response to William Gibson’s Pattern Recognition with its many simulacra, its worlds within worlds, and its fraud investigator Maxine Tarnow, much like Cayce Pollard, trying to make sense of some digital plot tied in with organized crime as the very real factor of family comes increasingly closer into the picture.

Thomas Pynchon, Bleeding Edge: Several reviewers were needlessly hostile to Pynchon’s latest volume, blaming the famous recluse for not delivering another Gravity’s Rainbow. But Bleeding Edge is not only a very funny book stacked to the nines with references (meticulously documented by the good folks at Pynchon Wiki). It’s a loving and sometimes irreverent portrait of the end of the 20th century and perhaps the end of America’s soul, reading at times like a call and response to William Gibson’s Pattern Recognition with its many simulacra, its worlds within worlds, and its fraud investigator Maxine Tarnow, much like Cayce Pollard, trying to make sense of some digital plot tied in with organized crime as the very real factor of family comes increasingly closer into the picture.

Roxana Robinson, Sparta: It’s absolutely criminal that Roxana Robinson’s carefully observed study of an Iraq War veteran returning home hasn’t received wider recognition. Perhaps some readers were too busy wasting their time blasting Jonathan Franzen over his latest grumbling or writing another installment in the meaningless snark vs. smarm war. Whatever the reason, it’s a poor excuse to ignore this honed, gut-wrenching novel revealing just what happens when you cannot return to the life you gave up, along with the psychological costs of being left for dead even after you escape a mortal fate on the battlefield. Like Messud, Robinson probes with wisdom and sensitivity into every anger-inducing quality of her protagonist, Conrad Farrell, who cannot even be solaced by his classics education. As we come to realize that not even a stable family is panacea for PTSD or returning home without a clearly defined role, we begin to understand how callous this nation has been to the men we asked to do the dirty work. And if the “hard, burnished carapace” of spent men hollowed out Sparta, what is it doing to our nation today? This is a vital and needlessly ignored work of fiction. (Bat Segundo interview, 55 minutes)

Roxana Robinson, Sparta: It’s absolutely criminal that Roxana Robinson’s carefully observed study of an Iraq War veteran returning home hasn’t received wider recognition. Perhaps some readers were too busy wasting their time blasting Jonathan Franzen over his latest grumbling or writing another installment in the meaningless snark vs. smarm war. Whatever the reason, it’s a poor excuse to ignore this honed, gut-wrenching novel revealing just what happens when you cannot return to the life you gave up, along with the psychological costs of being left for dead even after you escape a mortal fate on the battlefield. Like Messud, Robinson probes with wisdom and sensitivity into every anger-inducing quality of her protagonist, Conrad Farrell, who cannot even be solaced by his classics education. As we come to realize that not even a stable family is panacea for PTSD or returning home without a clearly defined role, we begin to understand how callous this nation has been to the men we asked to do the dirty work. And if the “hard, burnished carapace” of spent men hollowed out Sparta, what is it doing to our nation today? This is a vital and needlessly ignored work of fiction. (Bat Segundo interview, 55 minutes)

Eric Schlosser, Command and Control: Thirty-three years ago, the United States came very close to a nuclear holocaust in Damascus, Arkansas. In a Titan II silo, an overworked airman dropped a socket wrench, which pierced the skin on the missile’s fuel tank, causing poisonous oxidizer to permeate through the air. The W-53 nuclear warhead mounted at the top of the missile came very close to exploding. This is all documented in Command and Control, which also covers our reckless history of avoiding safety and taking shortcuts to maintain missiles. It’s a sobering and necessary reminder on how unsafe we have been in the past and how reckless we may be operating today, as other nations develop the same nuclear capabilities (and concomitant measures) that we once had. (Bat Segundo interview, 56 minutes)

Eric Schlosser, Command and Control: Thirty-three years ago, the United States came very close to a nuclear holocaust in Damascus, Arkansas. In a Titan II silo, an overworked airman dropped a socket wrench, which pierced the skin on the missile’s fuel tank, causing poisonous oxidizer to permeate through the air. The W-53 nuclear warhead mounted at the top of the missile came very close to exploding. This is all documented in Command and Control, which also covers our reckless history of avoiding safety and taking shortcuts to maintain missiles. It’s a sobering and necessary reminder on how unsafe we have been in the past and how reckless we may be operating today, as other nations develop the same nuclear capabilities (and concomitant measures) that we once had. (Bat Segundo interview, 56 minutes)

Mark Slouka, Brewster: I’m going to confess that when I first read Mark Slouka’s novel, I was a little suspicious of its narrative swagger. Here was a book told from the story of a teenager named Jon Mosher who seemed to talk just a little too tough. But as I read on, I realized that this was the point. If you’re not part of the panorama that other people insist is the one to watch, then aren’t you going to speak a little louder? Brewster describes life in the more blue-collar area of upstate New York, portraying teenagers who didn’t have the bread to attend Woodstock and who need friendship to make it past the hidden brutality of daily life. Slouka is smart enough to reveal Brewster as a town where nearly everyone comes from somewhere else. Jon Mosher, the book’s narrator, portrays Ray Cappicciano is a sleek bad boy who can skim his finger across any metal surface. But as the reader gets to know Ray Cap, we come to understand how not being known reveals hidden torrents of other people’s cruelty. (Bat Segundo interview, 61 minutes)

Mark Slouka, Brewster: I’m going to confess that when I first read Mark Slouka’s novel, I was a little suspicious of its narrative swagger. Here was a book told from the story of a teenager named Jon Mosher who seemed to talk just a little too tough. But as I read on, I realized that this was the point. If you’re not part of the panorama that other people insist is the one to watch, then aren’t you going to speak a little louder? Brewster describes life in the more blue-collar area of upstate New York, portraying teenagers who didn’t have the bread to attend Woodstock and who need friendship to make it past the hidden brutality of daily life. Slouka is smart enough to reveal Brewster as a town where nearly everyone comes from somewhere else. Jon Mosher, the book’s narrator, portrays Ray Cappicciano is a sleek bad boy who can skim his finger across any metal surface. But as the reader gets to know Ray Cap, we come to understand how not being known reveals hidden torrents of other people’s cruelty. (Bat Segundo interview, 61 minutes)

Terry Teachout, Duke: Teachout’s biography of Duke Ellington is arguably his smoothest and best-researched book. Longlisted for the National Book Awards, Duke demonstrates, like the best of arts-related biographies, that it is as much about chronicling the culture that allowed Ellington to flourish as it is about revealing the niceties of this titanic jazz figure. Thanks to Teachout, I spent large chunks of a weekend listening to all sorts of music, tracing, for example, Bubber Miley’s solo on “East St. Louis Toodle-oo” to Jimi Hendrix’s wah-wah work on “All Along the Watchtower” after Teachout found a fascinating connection. I was happy to fall down this YouTube rabbit hole and follow the eventful ups and downs of a man who could be found dazzling audiences at the Newport Jazz Festival one minute and appearing with Herman’s Hermits on The Ed Sullivan Show the next. (Bat Segundo interview, 50 minutes)

Terry Teachout, Duke: Teachout’s biography of Duke Ellington is arguably his smoothest and best-researched book. Longlisted for the National Book Awards, Duke demonstrates, like the best of arts-related biographies, that it is as much about chronicling the culture that allowed Ellington to flourish as it is about revealing the niceties of this titanic jazz figure. Thanks to Teachout, I spent large chunks of a weekend listening to all sorts of music, tracing, for example, Bubber Miley’s solo on “East St. Louis Toodle-oo” to Jimi Hendrix’s wah-wah work on “All Along the Watchtower” after Teachout found a fascinating connection. I was happy to fall down this YouTube rabbit hole and follow the eventful ups and downs of a man who could be found dazzling audiences at the Newport Jazz Festival one minute and appearing with Herman’s Hermits on The Ed Sullivan Show the next. (Bat Segundo interview, 50 minutes)

Jeanne Theoharis, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks: Released at the beginning of the year, Theoharis’s meticulously researched volume of the woman who refused to give up her seat reveals a far more sophisticated and politically active figure than the one in the history books. This is a much needed replacement for such cheap hagiographies as David Brinkley’s Rosa Parks: A Life that reveals everything that happened after the famous day in Montgomery. It exposes the sexism of Black Power, shows how numerous statesmen attempted to co-opt Parks to gain extra footing during their careers, and illustrates the costs and personal hardships of being a revolutionary. (Follow Your Ears #5, “Rosa Parks: Not Just a Meek Seamstress” radio segment at 47:16)

Jeanne Theoharis, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks: Released at the beginning of the year, Theoharis’s meticulously researched volume of the woman who refused to give up her seat reveals a far more sophisticated and politically active figure than the one in the history books. This is a much needed replacement for such cheap hagiographies as David Brinkley’s Rosa Parks: A Life that reveals everything that happened after the famous day in Montgomery. It exposes the sexism of Black Power, shows how numerous statesmen attempted to co-opt Parks to gain extra footing during their careers, and illustrates the costs and personal hardships of being a revolutionary. (Follow Your Ears #5, “Rosa Parks: Not Just a Meek Seamstress” radio segment at 47:16)

Jesmyn Ward, Men We Reaped: Jesmyn Ward remains one of our most vital chroniclers of American life. This searing yet understated memoir examines why racism continues to flourish and why so many young black men continue to die. It looks into how five needless deaths, including West’s own brother, affected and informed her own life. It’s a deeply affecting book which points out how the deck is stacked against you if you’re a young African-American living in Mississippi. But it also reveals how stories allow us to live and understand and possibly break out of some of these vicious cycles. Maybe if we focus our attention into how other people live, we may just come up with a new way of storytelling that allows us to lob some stones at the incompetent political forces that would prefer to shut down our government than address our deepest needs and our greatest ills. (Bat Segundo interview, 42 minutes)

Jesmyn Ward, Men We Reaped: Jesmyn Ward remains one of our most vital chroniclers of American life. This searing yet understated memoir examines why racism continues to flourish and why so many young black men continue to die. It looks into how five needless deaths, including West’s own brother, affected and informed her own life. It’s a deeply affecting book which points out how the deck is stacked against you if you’re a young African-American living in Mississippi. But it also reveals how stories allow us to live and understand and possibly break out of some of these vicious cycles. Maybe if we focus our attention into how other people live, we may just come up with a new way of storytelling that allows us to lob some stones at the incompetent political forces that would prefer to shut down our government than address our deepest needs and our greatest ills. (Bat Segundo interview, 42 minutes)

* I also started another reading project, The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge. I am presently reading Ian Hacking’s The Taming of Chance and will be writing about the volumes before this in the next few weeks.