Anyone who has ever worked in an office is familiar with the self-styled “expert” who rolls in from London or New York. The grinning expert, who almost never listens to anything other than the hollow sound of his own voice, locks you into a conference room with a condescending four hour PowerPoint presentation. One often looks cautiously at such a mercenary, often paid an obscenely high sum for pablum, to see if he has a pistol concealed under the three piece suit. Why? Because the presenter’s vaguely sinister chest-thumping almost always feel more like a hostage situation rather than a true meeting of the minds.

Ego should never be the driving force when you advise other people. The collective journey must represent the true impetus behind any guiding effort. Unfortunately, the dreadful combination of arrogance and stupidity is an increasing affliction in American culture, which now prides itself on smearing a crowd with the soothing balm of anti-intellectualism, with hubris often serving as the prominent titanium dioxide. This strain was most recently evidenced by Tucker Carlson’s unintentionally hilarious but nevertheless dangerous notion that the metric system represents a conspiracy promulgated by revolutionaries. There are now too many circumstances in which wildly unqualified people — often illiterate and sloppy in their work product — anoint themselves as Napoleonic dictators for how to advance thought and who often do so without the nuts-and-bolts wisdom or attentive awareness that inspires people to conjure up truly incredible offerings.

I mention all this because I recently had the considerable displeasure of reading a typo-laden article written by a misguided audio dramatist who, while possessing a modicum of promising technical chops, remains tone-deaf to human behavior. To offer a charitable opinion, this dramatist is certainly doing the best he can, but his dialogue (which has included such inadvertent howlers as “Now dance with me, asshole,” “I envy your certainty,” and “I would have expected you to bring one of your underlings”) and anemic storytelling represents a form of “expertise” that my own very exacting standards for what constitutes art simply cannot accept.

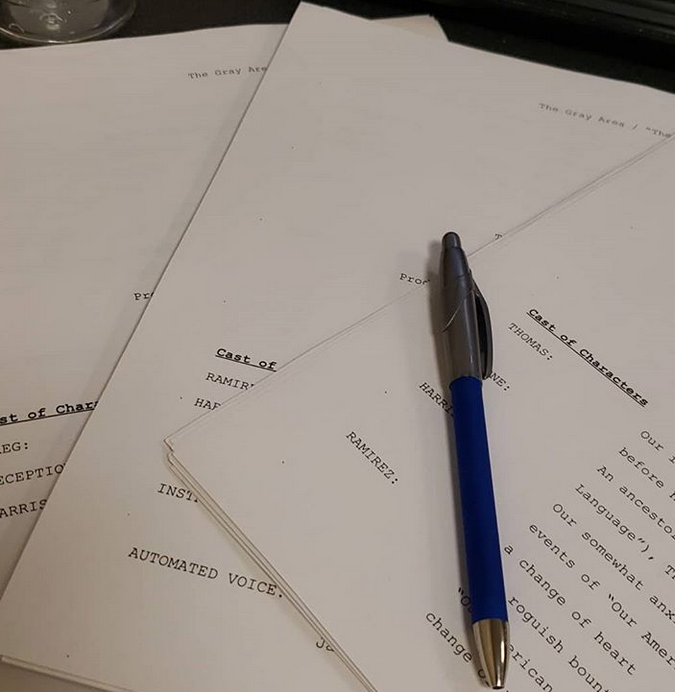

You see, I really believe that audio drama, like any artistic form, needs to be written and produced at the highest possible level. But to give this guy some credit, we do have to start somewhere! As someone who has written about 1,400 pages of audio drama and who often labors months over a script until it’s right (as opposed to someone who bangs out an entire season in nine weeks), as someone who has gone out into the real world for months to do journalistic research to ensure that I’m portraying groups of people and subcultures realistically and dimensionally rather than subscribing to self-congratulatory, attention-seeking tokenism that cheapens well-intentioned inclusiveness through the creation of shallow stereotypes, and as someone who won a distinguished award for all this, if you’ll pardon my own statement of qualifications here, I think I’m reasonably well-equipped to offer better suggestions. Having said that (and as a free-wheeling anti-authoritarian who despises groupthink, who has never held a gun in his life, and who is writing this in a T-shirt and jeans rather than a three piece suit), I would also like to encourage anyone reading these collected thoughts to poke holes into my views and to challenge anything that I present herein. This is, after all, the only way that all of us truly learn.

You see, I really believe that audio drama, like any artistic form, needs to be written and produced at the highest possible level. But to give this guy some credit, we do have to start somewhere! As someone who has written about 1,400 pages of audio drama and who often labors months over a script until it’s right (as opposed to someone who bangs out an entire season in nine weeks), as someone who has gone out into the real world for months to do journalistic research to ensure that I’m portraying groups of people and subcultures realistically and dimensionally rather than subscribing to self-congratulatory, attention-seeking tokenism that cheapens well-intentioned inclusiveness through the creation of shallow stereotypes, and as someone who won a distinguished award for all this, if you’ll pardon my own statement of qualifications here, I think I’m reasonably well-equipped to offer better suggestions. Having said that (and as a free-wheeling anti-authoritarian who despises groupthink, who has never held a gun in his life, and who is writing this in a T-shirt and jeans rather than a three piece suit), I would also like to encourage anyone reading these collected thoughts to poke holes into my views and to challenge anything that I present herein. This is, after all, the only way that all of us truly learn.

Audio drama is a magnificent medium. It shares much in common with literature in its ability to challenge an audience and convey emotional intimacy. And while shows such as The Bright Sessions, Wooden Overcoats, and The Truth intuitively comprehend the emotional connection between audio drama and audience, the medium, on the whole, is populated by too many engineering nerds who are not only incapable of writing quality scripts, but seem reluctant — if not outright hostile — to probe moral questions or explore any difficult ambiguities that lead to human insight.

Here are some better guidelines for how to approach the exciting and often greatly rewarding realm of audio dramatic writing!

1. Before anything else, think of HUMAN BEINGS.

This is the true big one. If you don’t have human beings guiding your audio drama, you are dead on arrival. And you become no different from some engineering nerd who is less interested in narrative possibility and more concerned with being the cleverest guy in the room. Being in touch with human behavior humbles you and opens you up to wonder and empathy and insatiable curiosity that you can not only pass onto your actors and your audience, but that will help you transform into a better and more mindful person. If you want to connect with an audience, then you need to know how to connect with people. And your art needs to reflect this. One of my favorite audio dramas, King Falls AM, has literally confined its setting to a call-in radio show in a small town. But its two main characters, Sammy and Ben, are human enough to warrant our attention. We learn over the series’ run that Sammy is gay and that Ben is smitten with Emily, the local librarian. And the show’s colorful characters and the creative team’s commitment to exploring the human have ensured that the show has never once lost momentum during its eighty-seven episodes. (There’s even a charming musical episode!)

It’s also vital for human behavior to contain paradoxes. Very often, that means taking major artistic risks with your characters — even making them “unlikable” if this is what the story calls for. I recently revisited some episodes of the science fiction TV series Blakes 7 after its star, the incredibly talented Paul Darrow, passed away. Darrow, who appeared in many audio dramas produced by Big Finish near the end of his life, played an antihero named Avon — a man who ended up as the leader of a band of revolutionaries fighting against a fascist empire known as the Federation. Why was Avon so interesting? Because he contained so many contradictions! He could be smart, intensely charming, paranoid, inclusive, sarcastic, and self-serving. Much like Walter White in Breaking Bad, you never quite knew how far Avon was going to go. And there is no better exemplar of why Avon worked so well than an episode called “Orbit” written by Robert Holmes (who also wrote some of the best episodes of Doctor Who). Avon and his longtime partner Vila have five minutes to rid a spacecraft of excess cargo weight. The two men are seen frantically running around, ejecting bits of plastic through the airlock. It’s clear that they’re not going to dump the cargo in time. Avon desperately asks Orac — the ship’s computer — how much weight the ship must lose in order to achieve escape velocity. Orac replies, “70 kilos.” With great ferocity, Avon shrieks, “Dammit! What weighs 70 kilos?” Orac responds with an alarming calmness, “Vila weighs 73 kilos, Avon.” And it is here that the scene becomes truly thrilling and surprising! Avon now has a solution — one that allows him to survive but that also involves betraying his friend. Darrow instantly transforms, grabs a laser pistol, and the scene is among the best in the entire run of the show. (You can watch the scene here.) As a test, I described this scene to a wide variety of people who were unfamiliar with speculative fiction. One old school guy in my Brooklyn hood who I’m friendly with (and for whom I have been serving as an occasional consultant on his webseries), “Damn! That’s some gangsta shit. I gotta check it out.” Human predicaments like this are universal.

Don’t worry too much about your sound design when you’re conceiving your story. You certainly need to remember that this is a medium driven by sound, but, if you’re doing audio drama right, your characters (and thus your actors) will be sharp and lively enough to conjure up a divergent sound environment. It’s absolutely foolhardy and creatively bankrupt to enslave your actors to a soundscape. This represents tyranny, not creative possibility. Actors need to be free to create in a fun and relaxed environment. (In my case, I cook all of my actors breakfast, compensate everyone instantly after recording, and try not to work them more than three hours per recording session.) As perspicacious as you may be, as certain as you may think you are about the rhythm and the delivery, your actors will always have fresh ideas that you haven’t considered. You need to have a script and a recording environment that is committed to your actors first. If you’re looking to be some petty despot, become some small-time corporate overlord. Don’t toil in art. If your actors are hindered by your dictatorial decisions as writer or director, they won’t be able to use their imagination. At all stages, audio drama is a process of collaborative discovery. When you write the script, it’s about creating memorable and three-dimensional characters. When you’re recording with actors, it’s about listening to how an actor interprets the characters and shaping the scene together with openness, trust, and experimentation. Then, when you’re putting together the rough edit (dialogue only), you have yet another stage of discovery. The actors have given you all that you need. You’ll be able to imagine where they are in a room, what they’re doing, and what else might be with them. From here, you start to form the sound design. Worldbuilding always comes from human investigation. And if you’re fully committed to the human, then your instinctive imagination will be able to devise a unique aural environment.

Don’t worry too much about your sound design when you’re conceiving your story. You certainly need to remember that this is a medium driven by sound, but, if you’re doing audio drama right, your characters (and thus your actors) will be sharp and lively enough to conjure up a divergent sound environment. It’s absolutely foolhardy and creatively bankrupt to enslave your actors to a soundscape. This represents tyranny, not creative possibility. Actors need to be free to create in a fun and relaxed environment. (In my case, I cook all of my actors breakfast, compensate everyone instantly after recording, and try not to work them more than three hours per recording session.) As perspicacious as you may be, as certain as you may think you are about the rhythm and the delivery, your actors will always have fresh ideas that you haven’t considered. You need to have a script and a recording environment that is committed to your actors first. If you’re looking to be some petty despot, become some small-time corporate overlord. Don’t toil in art. If your actors are hindered by your dictatorial decisions as writer or director, they won’t be able to use their imagination. At all stages, audio drama is a process of collaborative discovery. When you write the script, it’s about creating memorable and three-dimensional characters. When you’re recording with actors, it’s about listening to how an actor interprets the characters and shaping the scene together with openness, trust, and experimentation. Then, when you’re putting together the rough edit (dialogue only), you have yet another stage of discovery. The actors have given you all that you need. You’ll be able to imagine where they are in a room, what they’re doing, and what else might be with them. From here, you start to form the sound design. Worldbuilding always comes from human investigation. And if you’re fully committed to the human, then your instinctive imagination will be able to devise a unique aural environment.

But to get to this place, you need to have characters who are unusual and who contain subtlety, depth, and detailed background. What kind of family did they have? Are they optimistic or moody? What was their most painful experience? Their happiest? Are they passionate about anything? If you’re stuck, you could always try revisiting some personal experience. For “Brand Awareness,” a Black Mirror-like story about a woman who learns that the beer that she’s fiercely loyal to doesn’t actually exist, the premise was inspired by an incident in which I went to a Williamsburg bar, certain that I had ordered a specific Canadian beer there before. But when I mentioned the beer brand to the bartender, she didn’t know that it existed. (It turned out that I had the wrong bar.) I laughed over how ridiculously loyal I had been to the Canadian beer brand and began asking questions about why I was so stuck on that particular beer at that time. I then came up with the idea of a woman who spent much of her time collecting memorabilia for a beer called Eclipse Ale, one that nobody knew about, and decided, instead of making this character a rabid and obsessive fan, to make her very real. I placed her in a troubled relationship with a man who refused to listen to her, which then gave me an opportunity to explore the harms of patriarchy. I then had to answer the question of why this woman was the only one who knew about the beer and conjured up the idea of a boutique hypnotist who served in lieu of couples therapy. Suddenly I had a weird premise and some sound ideas. What did the memorabilia look like? What were the hypnotist’s methods like? Ultimately, most of my sound design came from my incredible cast. Their interpretations were so vivid that I began to create a soundscape that enhanced and reflected their performances. The process was so fun that our team’s collective imagination took care of everything. I would listen to the rough dialogue assembly on my headphones and physically act out each character as they were talking into my ears. And from here, I was able to see what the space looked like. I went to numerous bars and closed my eyes and listened and used this as the basis for how to shape the scene. These methods allowed me to tell a goofy but ultimately realistic story.

But to get to this place, you need to have characters who are unusual and who contain subtlety, depth, and detailed background. What kind of family did they have? Are they optimistic or moody? What was their most painful experience? Their happiest? Are they passionate about anything? If you’re stuck, you could always try revisiting some personal experience. For “Brand Awareness,” a Black Mirror-like story about a woman who learns that the beer that she’s fiercely loyal to doesn’t actually exist, the premise was inspired by an incident in which I went to a Williamsburg bar, certain that I had ordered a specific Canadian beer there before. But when I mentioned the beer brand to the bartender, she didn’t know that it existed. (It turned out that I had the wrong bar.) I laughed over how ridiculously loyal I had been to the Canadian beer brand and began asking questions about why I was so stuck on that particular beer at that time. I then came up with the idea of a woman who spent much of her time collecting memorabilia for a beer called Eclipse Ale, one that nobody knew about, and decided, instead of making this character a rabid and obsessive fan, to make her very real. I placed her in a troubled relationship with a man who refused to listen to her, which then gave me an opportunity to explore the harms of patriarchy. I then had to answer the question of why this woman was the only one who knew about the beer and conjured up the idea of a boutique hypnotist who served in lieu of couples therapy. Suddenly I had a weird premise and some sound ideas. What did the memorabilia look like? What were the hypnotist’s methods like? Ultimately, most of my sound design came from my incredible cast. Their interpretations were so vivid that I began to create a soundscape that enhanced and reflected their performances. The process was so fun that our team’s collective imagination took care of everything. I would listen to the rough dialogue assembly on my headphones and physically act out each character as they were talking into my ears. And from here, I was able to see what the space looked like. I went to numerous bars and closed my eyes and listened and used this as the basis for how to shape the scene. These methods allowed me to tell a goofy but ultimately realistic story.

I can’t stress this next point enough. Audio drama should never be about being overly clever or showy. It should be designed with enough depth for the audience to use its imagination. Just as I consider the actors on my production to be my creative equals, I also consider the audience to my interpretive equal. Their takeaways from my show are almost always smarter than my own. It would be colossally arrogant of me to assume that I know better than them.

To return to the gentleman who wrote the article that I am partially responding to here, his advice concerning character tips should be avoided at all costs. Robots can be fun, but, however ephemerally vivid they can be, they are among the most tedious one-note characters you can ever drop into a story. Moreover, a character who appears on only two pages should have as much backstory as one of your principals. When the great Robert Altman made one of his masterpieces, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, he instructed all of the extras who were part of the Western town to develop detailed characters. This is one significant reason why that incredible film feels so real and so atmospheric. When in doubt, write vivid human characters with real problems. They always sound cool.

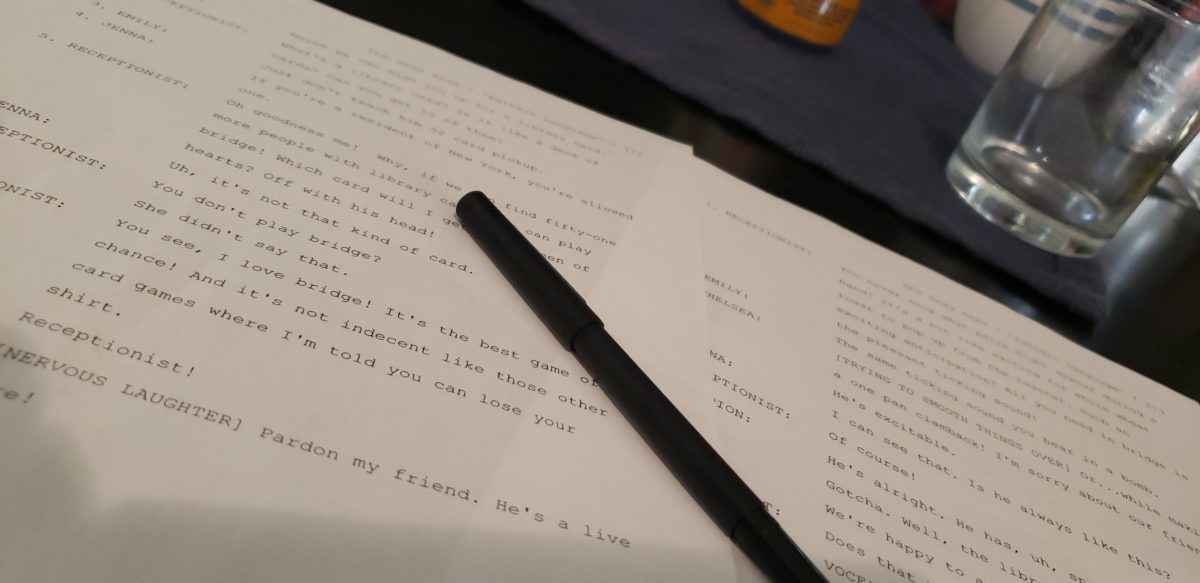

The misguided dramatist also reveals how pedestrian and unambitious he is in his storytelling when he tells you that you shouldn’t have more than four separate voices in a scene. This is only a problem if, like the misguided dramatist, you are too reliant upon seemingly clever ideas and don’t know how to write recognizable characters. If your characters are dimensional, then your audience will be able to follow the story. But you can also have your characters forget the names of the people who they are with so that you have an opportunity to remind your audience who they are. There are, after all, few people who attend a party and who manage to remember everybody’s first names. This expositional move doubles as a touch of realism and a subtle way of helping your audience keep track of a very large cast. Don’t squelch your ambition! If the dialogue is natural and the rhythm reflects real human conversation, then this will also help your audience lock into the narrative.

The misguided dramatist also reveals how pedestrian and unambitious he is in his storytelling when he tells you that you shouldn’t have more than four separate voices in a scene. This is only a problem if, like the misguided dramatist, you are too reliant upon seemingly clever ideas and don’t know how to write recognizable characters. If your characters are dimensional, then your audience will be able to follow the story. But you can also have your characters forget the names of the people who they are with so that you have an opportunity to remind your audience who they are. There are, after all, few people who attend a party and who manage to remember everybody’s first names. This expositional move doubles as a touch of realism and a subtle way of helping your audience keep track of a very large cast. Don’t squelch your ambition! If the dialogue is natural and the rhythm reflects real human conversation, then this will also help your audience lock into the narrative.

Also, I don’t know what living rooms the misguided dramatist spends his time in. But every setting is driven by sound. Only the most unimaginative and inattentive dramatist in the world would gainsay the textural possibilities contained in a car or a kitchen. These are seemingly familiar places. But if you spend enough time in various kitchens and simply listen, you’ll discover that each kitchen does have a separate tapestry of distinct sounds.

As for momentum, I have one firm rule: Have at least something on every page that drives the story forward (or, failing that, a good joke). If it’s not there, then cut and revise the page until you get to that ratio. Because you have exactly five minutes from the beginning of your show to grab your audience. If you’re bombarding your audience with over-the-top sound design out of creative desperation but you don’t have anything human to back it up, you’re dead. The audience will tune out very quickly, especially when there are so many other audio drama productions up to the task. However, if you’re concerned with the human first, then you’ll be on firm footing. The misguided dramatist writes, “The specifics don’t matter.” Oh, but they always matter. This is a profoundly ignorant and offensive statement that ignores the lessons contained in centuries of dramatic writing. Having some random kid walking by with a blasting boombox may pump up your hubris enough to approach the editors of Electric Literature and say, “Hey, I’m an expert! Can I write an article and pimp my show?” But if your inclusion doesn’t serve the human needs of the story, it’s gratuitous. It’s flexing your muscle rather than lifting the weights. And as you make more audio drama, it’s vital that you never stop evolving. In an increasingly crowded world of audio drama options, you want to be the dramatist who can bench-press to the best of your ability. And you’re going to want to build yourself up so that you can increase the load you can heave above your shoulders. You don’t stay in shape if you stop hitting the gym. And art rarely works when you phone it in. It involves hard work, great care, and daily discipline.

2. Imagination.

Well, I can mostly agree with the misguided dramatist here. You definitely want to paint a picture in your audience’s minds. But you don’t necessarily have to do this with a melange of bad exposition such as “Teeth, there’s too many teeth.” All you need to do is to imagine how a human being would react to a set of circumstances and then slightly style the dialogue so that it reveals just enough exposition (but not too much). You can then sculpt the sound design accordingly.

3. On “Gross” Sound Design

Once again, the misguided dramatist lacks the ability to comprehend how an audience vicariously relates to an audio drama. You can do kissing in audio drama. I’ve included it in The Gray Area. This doesn’t mean that you drop in a flagrant smooch that’s going to drown out everything else in the mix. You want a dramatic kiss to sound pretty close to how it’s actually experienced. For the first season, I recorded some kissing foley with someone I was dating at the time. It was one of the strangest experiences of my life, perhaps the closest I’ve come to feeling like a pornographic actor. But it had to be done for art! Imagine two people lying in bed, both of them with headphones on, and a condenser microphone mounted just above them. We proceeded to kiss until I got the levels and the mic positioned just right for a very soft sound that is quite close to the sound that you hear when you kiss someone. This was a little difficult. Because I very much enjoyed kissing the person in question. But I was able to find the right balance. And I mixed this into the story quite gently and subtly so that it wouldn’t intrude upon the story. The Amelia Project has a character who very much enjoys cocoa, yet the slurps and stirs of the spoon never sound intrusive. And that is because the producers are smart enough to understand that flagrant foley of natural human sounds is going to sound “gross.” But you do have an obligation to depict the human and that includes sounds that might be categorized as uncomfortable.

Once again, the misguided dramatist lacks the ability to comprehend how an audience vicariously relates to an audio drama. You can do kissing in audio drama. I’ve included it in The Gray Area. This doesn’t mean that you drop in a flagrant smooch that’s going to drown out everything else in the mix. You want a dramatic kiss to sound pretty close to how it’s actually experienced. For the first season, I recorded some kissing foley with someone I was dating at the time. It was one of the strangest experiences of my life, perhaps the closest I’ve come to feeling like a pornographic actor. But it had to be done for art! Imagine two people lying in bed, both of them with headphones on, and a condenser microphone mounted just above them. We proceeded to kiss until I got the levels and the mic positioned just right for a very soft sound that is quite close to the sound that you hear when you kiss someone. This was a little difficult. Because I very much enjoyed kissing the person in question. But I was able to find the right balance. And I mixed this into the story quite gently and subtly so that it wouldn’t intrude upon the story. The Amelia Project has a character who very much enjoys cocoa, yet the slurps and stirs of the spoon never sound intrusive. And that is because the producers are smart enough to understand that flagrant foley of natural human sounds is going to sound “gross.” But you do have an obligation to depict the human and that includes sounds that might be categorized as uncomfortable.

4. Be Careful with Foley Description

I learned early on that writing four seemingly simple words (“GIANT RATS SCAMPERING AROUND”) created far more trouble for me in post-production than I anticipated. And while I enjoyed the challenge that I presented myself, I spent a week banging my head against my desk before I finally stumbled on a sound design solution. If you’re working with a sound designer, try to be mindful of the difficulty in coming up with sounds that reflect creatures or concepts that don’t exist in the real world. Even if you add “LIKE HORSES GALLOPING” to the giant rats description, that’s going to offer the sound designer some creative ideas that will make it easier for her to imagine and come up with something. If you’re collaborating with a sound designer, you need to offer a clear blueprint for her to create and imagine. Make no mistake: the sound designer is just as much of an actor as an actor.

5. Don’t Be Afraid to Take Risks

You’re not going to please everyone. So why spend so much time worrying about it? There are incredibly talented and impeccably kind people who produce beloved audio dramas and even they receive hate mail and vicious criticism. Critics, by and large, are far less useful than the honest and experienced people you have in your corner who understand both you and the hard work that goes into making audio drama. You need to be surrounded by beta readers and beta listeners who will not bullshit you. Your duty as an artist is to not give into the often insane demands of rabid fans (much as one very popular audio drama did a few years ago, forcing this truly terrific show to ignobly close its doors) and to concentrate on putting out your best work. The real crowd, your truly loyal listeners and the ones who you actually learn from, will trust you enough to continue with the journey. The same goes with your actors. I took a huge risk on a Season 2 script. And I was incredibly surprised, humbled, and honored when the actors were crazy about it and told me what a thrilling twist it was and brought their A game when we recorded. You have a duty to keep on growing. Keep in mind that critics, especially the small-time character assassins on Twitter driven by acute resentment, reflect a vocal minority. You’re also probably never going to get a TV deal. So why chase that kind of outsize success? Besides, it’s far more rewarding to tell stories entirely on your own terms. If the work is good and you treat people well, you will attract very talented actors. And they in turn will tell their actor friends about how much fun you are to work with. But if you tell the same story over and over again, or you aren’t sufficiently answering the many questions you’ve set up, chances are you’ll be pulling a Damon Lindelof. And everyone will rightfully ding you for writing a lazy and inane climax.

You’re not going to please everyone. So why spend so much time worrying about it? There are incredibly talented and impeccably kind people who produce beloved audio dramas and even they receive hate mail and vicious criticism. Critics, by and large, are far less useful than the honest and experienced people you have in your corner who understand both you and the hard work that goes into making audio drama. You need to be surrounded by beta readers and beta listeners who will not bullshit you. Your duty as an artist is to not give into the often insane demands of rabid fans (much as one very popular audio drama did a few years ago, forcing this truly terrific show to ignobly close its doors) and to concentrate on putting out your best work. The real crowd, your truly loyal listeners and the ones who you actually learn from, will trust you enough to continue with the journey. The same goes with your actors. I took a huge risk on a Season 2 script. And I was incredibly surprised, humbled, and honored when the actors were crazy about it and told me what a thrilling twist it was and brought their A game when we recorded. You have a duty to keep on growing. Keep in mind that critics, especially the small-time character assassins on Twitter driven by acute resentment, reflect a vocal minority. You’re also probably never going to get a TV deal. So why chase that kind of outsize success? Besides, it’s far more rewarding to tell stories entirely on your own terms. If the work is good and you treat people well, you will attract very talented actors. And they in turn will tell their actor friends about how much fun you are to work with. But if you tell the same story over and over again, or you aren’t sufficiently answering the many questions you’ve set up, chances are you’ll be pulling a Damon Lindelof. And everyone will rightfully ding you for writing a lazy and inane climax.

Formulaic writing may win you an audience. There is no shortage of box office successes that are more generic than a supermarket aisle populated by no name yellow boxes. But are you writing for short-term lucre and attention or long-term artistic accomplishment? Are you writing audio drama to grow as a person and as an artist? Always remember that the work is its own reward. And that means taking risks.

6. Be Passionate About Your Story at All Times

Don’t write a script just for the sake of writing a script. If you’re telling a story, it has to be something that you absolutely believe in. Your vision must be large and passionate enough to get other people excited about it. You must also be committed to surprising yourself at all stages. (It also helps that I’m crazy about everyone who works on this show and am naturally quite thrilled to watch them get better as performers.) While I have drafted a four season plan for The Gray Area (and have a “Bible” of twenty prototypical scripts), the plan is just loose enough for me to continually invent with each season. I don’t write scripts from an outline (although I have done so in writing for other people). Because I find that, if I know where a story is heading, then it’s not going to be fun for me. After all, if I’m not surprised, why would I expect my audience to be?

If you’re just phoning it in, then why would you expect your actors to give their all? One audio drama producer recently revealed a horror story about one regular actor leaving midway through the series. But listening to the audio drama, it’s easy to see why. The passion contained in the initial episodes plummeted in later episodes. A friend, who was an initial fan of the show, texted me, asking “What happened? It was so good! Now I can’t listen to it!” Well, I responded, the character in question, despite being played by a lively actor who clearly has much to offer, became one-note and confined to a sterile environment. And why would any actor want to stay involved with a character who remains stagnant? If you don’t feed your actors with true passion, and if you don’t take care of them, then you’re not living up to the possibilities of audio drama.

At all stages of The Gray Area, I talk with my actors and tell them what I have planned for their characters over many seasons. I listen to their passions and interests. I regularly check in on them. I try to attend their shows when they perform on stage. Because it is my duty to remain committed to my talent. All this gives me many opportunities to find out where actors wish to push themselves as performers and to suss out emotional areas that other directors don’t seem to see. I cast comedic actors in dramatic roles. I point out to some of my more emotionally intense actors how funny they are and write stories with this in mind. I have to keep my characters growing so that I can sustain an atmosphere committed to true creative freedom. Because I love and adore and greatly respect the people I work with and I want to make sure that these actors are always having fun and that they feel free to create. I’ve got this down so well that, when the actors find out I’m writing a new slate of scripts, they playfully nag me, wondering when the stories are going to be done.

If you’re doing audio drama right, you’re probably going to be surprised to find yourself exhausted after a long day. The fatigue seems inconceivable because you were having so much fun. But it does mean that you were driven by passion first, buttressed by hard work. And that will ultimately be reflected in the final product.

7. There Are Many Ways to Make Audio Drama

There’s recently been some discussion about establishing a set of critical standards that all producers should agree upon for the “greater good.” I find this to be a bunch of prescriptive malarkey, more of a popularity contest and an ego-stroking exercise rather than a true exchange of viewpoints. Take the advice that you can use and ignore the rest. That includes this article. If you see something here that whiffs untrue, ignore it. Or leave a comment here and challenge me. I’d love to hear your dissenting views! I’m offering one way to make audio drama, but there are dozens of ways to go about it.

8. Be Wide-Ranging in Your Influences

Don’t just listen to audio drama. Listen to nonfiction podcasts. Read books. Take on hobbies and interests that you’ve never tried. Play music. Above all, live life. Existence is always the most important influence. I’ve listened to far too many bad audio dramas trying to offer cut-rate knockoffs of popular shows. This isn’t a recipe for success or artistic growth. You need to find your own voice and be true to who you are as much as you can. Every story has already been told. But it hasn’t been told in the way that you express it.

(I hope that some of what I’ve imparted here has been useful! For anyone who’s interested, I am presently in the final weeks of production on the second season of my audio drama. I’ve been documenting my journey on Instagram, passing along any tips or tricks I discover along the way so that other audio dramatists don’t make the same mistakes that I have! Plus, there are many fun behind-the-scenes videos and photos. Feel free to check out @grayareapod and say hello. We’re all in this journey of making audio drama together! It’s a very exciting time to tell stories for the ear!)

You see, I really believe that audio drama, like any artistic form, needs to be written and produced at the highest possible level. But to give this guy some credit, we do have to start somewhere! As someone who has written about 1,400 pages of audio drama and who often labors months over a script until it’s right (as opposed to someone who

You see, I really believe that audio drama, like any artistic form, needs to be written and produced at the highest possible level. But to give this guy some credit, we do have to start somewhere! As someone who has written about 1,400 pages of audio drama and who often labors months over a script until it’s right (as opposed to someone who  Don’t worry too much about your sound design when you’re conceiving your story. You certainly need to remember that this is a medium driven by sound, but, if you’re doing audio drama right, your characters (and thus your actors) will be sharp and lively enough to conjure up a divergent sound environment. It’s absolutely foolhardy and creatively bankrupt to enslave your actors to a soundscape. This represents tyranny, not creative possibility. Actors need to be free to create in a fun and relaxed environment. (In my case, I cook all of my actors breakfast, compensate everyone instantly after recording, and try not to work them more than three hours per recording session.) As perspicacious as you may be, as certain as you may think you are about the rhythm and the delivery, your actors will always have fresh ideas that you haven’t considered. You need to have a script and a recording environment that is committed to your actors first. If you’re looking to be some petty despot, become some small-time corporate overlord. Don’t toil in art. If your actors are hindered by your dictatorial decisions as writer or director, they won’t be able to use their imagination. At all stages, audio drama is a process of collaborative discovery. When you write the script, it’s about creating memorable and three-dimensional characters. When you’re recording with actors, it’s about listening to how an actor interprets the characters and shaping the scene together with openness, trust, and experimentation. Then, when you’re putting together the rough edit (dialogue only), you have yet another stage of discovery. The actors have given you all that you need. You’ll be able to imagine where they are in a room, what they’re doing, and what else might be with them. From here, you start to form the sound design. Worldbuilding always comes from human investigation. And if you’re fully committed to the human, then your instinctive imagination will be able to devise a unique aural environment.

Don’t worry too much about your sound design when you’re conceiving your story. You certainly need to remember that this is a medium driven by sound, but, if you’re doing audio drama right, your characters (and thus your actors) will be sharp and lively enough to conjure up a divergent sound environment. It’s absolutely foolhardy and creatively bankrupt to enslave your actors to a soundscape. This represents tyranny, not creative possibility. Actors need to be free to create in a fun and relaxed environment. (In my case, I cook all of my actors breakfast, compensate everyone instantly after recording, and try not to work them more than three hours per recording session.) As perspicacious as you may be, as certain as you may think you are about the rhythm and the delivery, your actors will always have fresh ideas that you haven’t considered. You need to have a script and a recording environment that is committed to your actors first. If you’re looking to be some petty despot, become some small-time corporate overlord. Don’t toil in art. If your actors are hindered by your dictatorial decisions as writer or director, they won’t be able to use their imagination. At all stages, audio drama is a process of collaborative discovery. When you write the script, it’s about creating memorable and three-dimensional characters. When you’re recording with actors, it’s about listening to how an actor interprets the characters and shaping the scene together with openness, trust, and experimentation. Then, when you’re putting together the rough edit (dialogue only), you have yet another stage of discovery. The actors have given you all that you need. You’ll be able to imagine where they are in a room, what they’re doing, and what else might be with them. From here, you start to form the sound design. Worldbuilding always comes from human investigation. And if you’re fully committed to the human, then your instinctive imagination will be able to devise a unique aural environment. But to get to this place, you need to have characters who are unusual and who contain subtlety, depth, and detailed background. What kind of family did they have? Are they optimistic or moody? What was their most painful experience? Their happiest? Are they passionate about anything? If you’re stuck, you could always try revisiting some personal experience. For

But to get to this place, you need to have characters who are unusual and who contain subtlety, depth, and detailed background. What kind of family did they have? Are they optimistic or moody? What was their most painful experience? Their happiest? Are they passionate about anything? If you’re stuck, you could always try revisiting some personal experience. For  The misguided dramatist also reveals how pedestrian and unambitious he is in his storytelling when he tells you that you shouldn’t have more than four separate voices in a scene. This is only a problem if, like the misguided dramatist, you are too reliant upon seemingly clever ideas and don’t know how to write recognizable characters. If your characters are dimensional, then your audience will be able to follow the story. But you can also have your characters forget the names of the people who they are with so that you have an opportunity to remind your audience who they are. There are, after all, few people who attend a party and who manage to remember everybody’s first names. This expositional move doubles as a touch of realism and a subtle way of helping your audience keep track of a very large cast. Don’t squelch your ambition! If the dialogue is natural and the rhythm reflects real human conversation, then this will also help your audience lock into the narrative.

The misguided dramatist also reveals how pedestrian and unambitious he is in his storytelling when he tells you that you shouldn’t have more than four separate voices in a scene. This is only a problem if, like the misguided dramatist, you are too reliant upon seemingly clever ideas and don’t know how to write recognizable characters. If your characters are dimensional, then your audience will be able to follow the story. But you can also have your characters forget the names of the people who they are with so that you have an opportunity to remind your audience who they are. There are, after all, few people who attend a party and who manage to remember everybody’s first names. This expositional move doubles as a touch of realism and a subtle way of helping your audience keep track of a very large cast. Don’t squelch your ambition! If the dialogue is natural and the rhythm reflects real human conversation, then this will also help your audience lock into the narrative.  Once again, the misguided dramatist lacks the ability to comprehend how an audience vicariously relates to an audio drama. You can do kissing in audio drama. I’ve included it in

Once again, the misguided dramatist lacks the ability to comprehend how an audience vicariously relates to an audio drama. You can do kissing in audio drama. I’ve included it in  You’re not going to please everyone. So why spend so much time worrying about it? There are incredibly talented and impeccably kind people who produce beloved audio dramas and even they receive hate mail and vicious criticism. Critics, by and large, are far less useful than the honest and experienced people you have in your corner who understand both you and the hard work that goes into making audio drama. You need to be surrounded by beta readers and beta listeners who will not bullshit you. Your duty as an artist is to not give into the often insane demands of rabid fans (much as one very popular audio drama did a few years ago, forcing this truly terrific show to ignobly close its doors) and to concentrate on putting out your best work. The real crowd, your truly loyal listeners and the ones who you actually learn from, will trust you enough to continue with the journey. The same goes with your actors. I took a huge risk on a Season 2 script. And I was incredibly surprised, humbled, and honored when the actors were crazy about it and told me what a thrilling twist it was and brought their A game when we recorded. You have a duty to keep on growing. Keep in mind that critics, especially the small-time character assassins on Twitter driven by acute resentment, reflect a vocal minority. You’re also probably never going to get a TV deal. So why chase that kind of outsize success? Besides, it’s far more rewarding to tell stories entirely on your own terms. If the work is good and you treat people well, you will attract very talented actors. And they in turn will tell their actor friends about how much fun you are to work with. But if you tell the same story over and over again, or you aren’t sufficiently answering the many questions you’ve set up, chances are you’ll be pulling a Damon Lindelof. And everyone will rightfully ding you for writing a lazy and inane climax.

You’re not going to please everyone. So why spend so much time worrying about it? There are incredibly talented and impeccably kind people who produce beloved audio dramas and even they receive hate mail and vicious criticism. Critics, by and large, are far less useful than the honest and experienced people you have in your corner who understand both you and the hard work that goes into making audio drama. You need to be surrounded by beta readers and beta listeners who will not bullshit you. Your duty as an artist is to not give into the often insane demands of rabid fans (much as one very popular audio drama did a few years ago, forcing this truly terrific show to ignobly close its doors) and to concentrate on putting out your best work. The real crowd, your truly loyal listeners and the ones who you actually learn from, will trust you enough to continue with the journey. The same goes with your actors. I took a huge risk on a Season 2 script. And I was incredibly surprised, humbled, and honored when the actors were crazy about it and told me what a thrilling twist it was and brought their A game when we recorded. You have a duty to keep on growing. Keep in mind that critics, especially the small-time character assassins on Twitter driven by acute resentment, reflect a vocal minority. You’re also probably never going to get a TV deal. So why chase that kind of outsize success? Besides, it’s far more rewarding to tell stories entirely on your own terms. If the work is good and you treat people well, you will attract very talented actors. And they in turn will tell their actor friends about how much fun you are to work with. But if you tell the same story over and over again, or you aren’t sufficiently answering the many questions you’ve set up, chances are you’ll be pulling a Damon Lindelof. And everyone will rightfully ding you for writing a lazy and inane climax.