Stephen Fry appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #432. He is most recently the author of The Fry Chronicles.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Basking in a pleasant tsunami of erudition.

Author: Stephen Fry

Subjects Discussed: Journalists who attack morally and spiritually, capitulating an iPhone, the number of gadgets that Fry carries on him, physical books vs. ebooks, high school physics lessons and vacillating ideas about the atom, books and mass, Anthony Powell’s Books Do Furnish a Room, technological developments and misunderstanding about replacement, ways in which technologies complement each other, the plight of newspapers, Page One, whether The New York Times is a trusted platform, accepting the fact that Gaddafi is dead, embedded journalists, Kickstarter campaigns and journalism, working for free in the post-Internet age, Fry’s presence on Twitter, Twitter vs. newspapers, not giving print interviews, the achievements of journalists, terrorists who rely on newspapers, the difficulties of not reporting serious changes to the Manhattan skyline, “cheating” on essays in school by writing them in advance, Fry’s ability to recall books by line number and specific edition, Shakespeare, hypothetical exam answers to Macbeth, the Wooly Willy, the pointlessness of exams, Fry’s love for technology, what education can learn from the ancient Greeks, the numerous intellectual trajectories which spring from coffee, Diderot, Secessionist Viennese coffeeshops, Gustav Klimt, the value of giving someone a single word to jump off from, Oscar Wilde’s “De Profundis,” Lord Alfred Douglas, the Oxford manner, education as “the ability to play gracefully with ideas,” intelligence rooted around connection, the No Child Left Behind Act, Diane Ravitch’s The Death and Life of the Great American School System, the etymology of “draconian,” vocational training, fruit trees, people who believe the Alps to be dull, those who blame teachers, having a busy schedule, Fry’s schedule vs. a politician’s schedule, not knowing things and greed, Fry’s shaky terpsichorean skills, humans and language, Steven Pinker, Guy Deutscher, how tenses imply futurity, animals and sex, the Phoenicians and writing, cuneiform and the alphabet, hip-hop, Fry’s rapping talent, forgetting to delight in the beauty of language, Wodehousian language rhythms and music, connections between Wodehouse, Cicero, and W.S. Gilbert, film adaptations of The Importance of Being Earnest, Jewish and gay identity, the linguistic roots of Shoah, 19th century anti-Semitism, meeting Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, playing Schumann’s Träumerei on the cello for Josef Mengele, when human beings are treated like machines, Hannah Arendt, Ring Lardner’s golden rule for screenwriting, political correctness, restrictions on the depictions of smoking in BBC documentaries and drama, Spooks, bizarre moral standards on British television, being exploited by Stephen Sondheim for a scavenger hunt, having a fax machine in the early days, Fry’s efforts to read Atlas Shrugged, the 1949 film adaptation of The Fountainhead, writing the book for Me and My Girl, the fine aural distinctions between a fax machine and a 56k modem, the 21st century audience for Ayn Rand, maniacal ideologies that don’t include joy or hope, the RAND Corporation, the Tea Party, reasonable addictions vs. extreme addictions, empathy, false categories when contemplating what it is to be human, Artistole’s “man is a political animal,” Kant’s symbolic logic, the behavioral thrust of David Hume, the readability of philosophers, TE Hulme’s influence on Pound and the modernists, moralists, Hulme’s “concrete flux of interpenetrating intensities,” humans being verbs rather than nouns, doctors and diagnosis-based language, referring to people by their condition, kindness and cheerfulness as essential virtues, eudaimonism, Mad cartoons, the “pay it forward” principle, Fry’s aborted career as a book reviewer, whether criticism is necessary, thick skins vs. thin skins, not wanting to hurt people’s feelings, Alec Guinness’s rude remarks to other actors, Paul Eddington, The Browning Version, Fry’s desire to play Crocker-Harris, pathetic efforts to be polite, Fry’s futile efforts to hawk his own book, teaching Aeschylus to inspire, cruelty, “Never presume to understand another man’s marriage,” ethics and absolute evil, Schindler’s Ark, the French Resistance bombing restaurants, Fry’s Apple zeal in relation to Foxconn abuses, suicides at Foxconn, Steve Jobs vs. Henry Ford, Brave New World, Godwin’s law, Apple’s business in China, overseas industrialization, Alms for Oblivion, and why Fry believes Simon Raven is better than Anthony Powell.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: Tying these multifarious observations with what is in your book, I actually wanted to ask you about this intriguing period when you were at Cambridge. You describe how you were “cheating” on essays because you wrote all of the essays in advance in your head — to the point where you were able to cite chapter and verse.

Fry: Yes.

Correspondent: Specific lines down to the line number of Shakespeare. Specific critical reference works down to the publisher, the edition.

Fry: The review course.

Correspondent: Whether it was in trade or whether it was in hardcover. Rather extraordinary. And that you would actually tilt these essays in relation to the question that was asked of you.

Fry: That’s the point. Exactly. The point is: if you have an essay on Othello, if you have an essay on Anthony and Cleopatra — we’ll stick with Shakespeare just for the sake of a closed canon, so we can think about it — if you have an essay on Macbeth, you have a point of view. I know I can deliver 3,000 words very quickly on Macbeth if I know I can.

Correspondent: You have 45 minutes right now, man!

Fry: And the question is “The essence of Macbeth is the difference between the microcosm of Macbeth’s mind and the macrocosm of the real world,” say. Now that may not suit my thesis at all for Macbeth, which is actually to do with the way the poetry disintegrates as the play progresses. But I can make it exactly answer that question. You just have to polarize. You know, it’s like getting a magnet. Did you ever have it in — you probably were American. So I don’t know why I’m asking if you had them. Those little bald men with iron filings and a magnet and you used to make beards out of them.

Correspondent: That was, I think, before my time.

Fry: It probably was before your time. But that’s what you’re doing. You’re taking a magnet and you’re polarizing what you know. Now it’s kind of cheating. It’s not cheating really. Because I am passionate about Shakespeare. I love Shakespeare. But I’m very, very lazy when it comes to exams. And I also am aware that an examination is nothing other than the ability to pass an exam. And what use is that? You might as well say, “In order to qualify from Harvard University, you have to win a squash match. Or you have to do the best Lady Bracknell of your year. Then you’ll get your top degree.” But why is the ability to reproduce prepared pappy ideas about intellectual concepts on paper — why is that a good reason to give someone a job in a law firm, in Wall Street, or in a publishing company for that matter? And part of my love of technology, personally what I would love is, of course, to go all the way back to the days of ancient Greece where you had Aristotle and you had Plato and you had the Lyceum and you had the Academy. So you would actually have a master. And to me, this is how an ideal examination would go. It doesn’t matter what subject the person is reading, as we say in England, or studying, as you would say here. You would just say, “Coffee.” Now someone who’s reading history might just instantly start talking about the coffee shops and how they were banned by Charles II, how they then came back again under Queen Anne, and how they caused a movement with the coffee shops in Paris with Diderot and the Republic of Letters and Voltaire and the Enlightenment. Or they could talk about the Secessionist Viennese coffee shops of Mahler and Klimt and so on. And Stefan Zweig and the whole generation of intellectuals. Rilke and Kraus and so on. Or you could talk about coffee as: Is it an emulsion? Is it a solution? How is coffee grown? What is it as a cash crop? What is is politically? Ethically? That there are some countries who are not allowed to grow food that they can eat. They can only grow food that they can sell. Currency rates. It’s a geopolitical issue. You can talk about the history — here we are in a publisher’s office — about the coffee table book. You could talk about it as a medical student. You could talk about it as a stimulant. You could talk about caffeine.

Correspondent: Worker exploitation. Fair trade.

Fry: Yeah. Basically, what you want, if you’re examining someone, is just to give them a single word and watch them run with it. One of my absolutely favorite quotations — and I’ll try and get it right — is from “De Profundis,” the letter that Oscar Wilde wrote in prison to his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. Bosie, as he nicknamed him. The man who basically destroyed his life. The boy who destroyed his life. And at one point, he’s talking about Oxford, and he’s saying, “The fact that you didn’t get a first-class degree is a disgrace. Many first-class minds never achieve first-class degrees. The fact that you didn’t get any degree at all is no disgrace. Many first-class minds never finish their course and get their degrees. But what to me, Bosie, is unforgivable is that you never achieved what I believe used to be called” — he put in inverted commas — “the Oxford manner.” And he then says, “Which I take to mean the ability to play gracefully with ideas.” Isn’t that the most beautiful definition of education you’ve ever heard? The ability to play gracefully with ideas! So whether the idea be coffee, whether it be paper, whether it be homosexuality, whether it be floorboards, it doesn’t matter. Because intelligence is about connection.

Correspondent: Yes!

Fry: So an exam question that just says, “Discuss Shakespeare’s use of imagery in Measure for Measure.” Well, gah! Come on.

Correspondent: But it’s actually much worse here in America. I’m sure you’re familiar with the No Child Left Behind Act, which is imposing these draconian standards and is absolutely convinced that all schools can offer 100% competence adhering to these standards. As a result — and there’s a great book by Diane Ravitch called The Death and Life of the Great American School System.

Fry: Oh yes. I’ve heard about it.

Correspondent: Which outlines exactly what’s been going on. Which means that if the school doesn’t meet these draconian standards, it gets sanctioned. It can fire teachers and administrators who are considered to be failures.

Fry: The pedant in me would say that Draco was a leader of the Greek Republic at a time when every single crime was punishable by death. Which is what “draconian” really means. And I’m sure it isn’t draconian in that sense. (laughs)

Correspondent: But when the Oxford manner is in opposition like this…

Fry: I know what you mean.

Correspondent: …it’s difficult.

Fry: And even more in opposition to that is the other group of people, which tend to be the right-wing industrial nexus. Whatever you might call them. Those who have influence over politics who say that education actually is irrelevant. What matters is vocational training. And so they want people with MBAs. They want people with apprenticeships. They want people who don’t have a wide, broad education and the ability to play with ideas, but who can do very specific things. Like training. It’s training. and think of that in terms of a tree. You know how you used to train a fruit tree against a wall. You straightened out its branches. [begins spreading arms] You stapled them to the wall. And that’s it. And it bears fruit very efficiently. Now we’re human beings. We’re not fruit trees. And we’re certainly not there to have ourselves straightened out to produce fruit for the state. We’re here to question, to wonder, to oppose.

Correspondent: But you are extending your arms very impressively, resembling a branch.

Fry: Thank you very much.

Correspondent: So I think that if you wanted to be a fruit tree, you could. You have a good line in that.

Fry: (laughs) I’ve certainly been a good fruit. Whether or not I’m a tree — well, of course, by their fruits, shall ye know them.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Fry: But the education point is a really interesting one. And I don’t know what the answer to it is. I think, oddly enough, if I am educated, if I have an education, it’s obviously one I’ve given myself. Because that’s what, by definition, what all educations are. You’re drawn out. Nothing’s put in. You’re not a bucket that is filled by a good teacher. And one of the saddest things is when people say, “Ah, well, Shakespeare was ruined for me at school. Because I had a terrible Shakespeare teacher.” I would say back to them, “Yeah. It’s the Alps for me. I had this awful geography teacher. I just find the Alps so dull. Because I had this awful geography teacher.” I mean, it’s ridiculous. I think it’s either beautiful or it isn’t. You can’t blame a teacher for not being able to communicate its beauty. I can look at the Alps and see that they’re beautiful. And if you can’t look at Shakespeare and see that it’s beautiful, don’t blame a teacher. Blame yourself for not looking hard enough. And I know people don’t want to hear that. But that’s the answer.

Correspondent: And you get into that in the book. And I actually wanted to discuss this further. I mean, I’m in agreement that, okay, we are in a world of riches. We have more information available to us than at any point in human history. But at the same time, learning about apple trees, Shakespeare, or what not, this requires time. And if you are someone who is working two jobs, who is raising a kid, how do you factor that into your dismissal of…

Fry: I like that. Because I’m a gay actor who doesn’t do much…

Correspondent: (laughs) No, no, no. It’s not that at all.

Fry: No. I know you weren’t. But it is funny. I have to say — and I don’t mean this in a boastful way, but I have yet to share diaries with someone who is busier than I am. Including politicians. I’ve had meetings recently. I’m trying to get…

Correspondent: (laughs) Including politicians? Like who?

Fry: Well, they always say that every single hour of every day is taken up by…

Correspondent: Even the bathroom breaks and all that.

Fry: Yeah. Etcetera. And, of course, they are to some extent. But they’re not busier than me. Because that’s actually all stuff that’s done. And then when it’s done, it’s done. If you’re a writer and you have other things, it’s never finished. And I am a very, very busy person. But you may notice I’m quite tubby. It’s because I’m greedy. And if people say they don’t know anything, it’s only because they’re not greedy. They’re not greedy for knowledge. Sometimes an image I give is — imagine that the Mayor of Washington was told when he was a child, “Go to London. Because the streets are paved with gold.” If he knew that in every city, the sidewalks, as you call them here — the pavements were piled high with gold coins and it made a noise. It made a kind of clashing noise as you shuffled your way through it. And it was terrible. And you bumped into a beggar standing with his hat out, saying, “Please. Please. Give me some money. I’m poor. I can’t eat.” You’d look at him and go, “What? Look around you! Just bend down and pick it up!” And that’s what I feel when people say, “Oh, it’s all right for you. You went to Cambridge and were taught things. Oh, why can’t I? I don’t know about this stuff.” I just want to say, “Bend down and pick it up.” It’s never been more available. All it takes is greed. Curiosity.

Correspondent: You are in a country where most Americans don’t have a passport. You are in a country where they actually don’t know these options. I’ll give you a perfect existential example of my own. So the New York Public Library — if you go in that marvelous reading room, it’s capacious. Tables. Everything. It’s like, “Of course! I’m going to study. Because this is an environment totally made to not slack off in any way.” Right? But if you try to find a seat at a coffeehouse now, every single table is completely filled up with people with their laptops. And there’s often people who sit down and they have this board meeting vernacular. And you can’t get anything done. I mean, it’s to the point where it’s almost a Trail of Tears-like situation for me and my friends.

Fry: (laughs)

Correspondent: We have to go to the next coffeehouse before they discover it! But you can pretty much almost always get a seat at the New York Public Library. And the question is: What do we do to restore the balance? To get people understanding that, yes, the streets are paved with informational gold if you go and reach down and pick it up. What do you think?

Fry: To me, this is simply prejudice. It’s prejudice that comes from the gifts that nature never gave me. And they were coordination and music. Although I love music and I’m passionate about music and I listen to music every day and I collect music. I have musical heroes that are distinct and different. You may know that I made a film about Richard Wagner, which is very important to me. Partly because as a Jewish person, Wagner is always going to be traumatic if you love him. Because he was such a bestial anti-Semite. Of course, that was not his fault. Because he died fifty years before — literally fifty years before Hitler became Vice-Chancellor of Germany, who of course adored Wagner too. So I do love music. But I can’t do it. I can’t perform it. I can’t sing. I can play the odd note on the piano.

Correspondent: But can you dance?

Fry: Absolutely cannot dance! I can’t even begin to put myself in a position.

Correspondent: Have you tried to take ballroom dance lessons?

Fry: I would hate it! I would loathe it!

Correspondent: Come on, Stephen! Pick it up! The dance is right there! (laughs)

Fry: If you read my book, you would know my physical self-consciousness is extreme.

Correspondent: Yeah.

Fry: But bad as this sounds, and this is no complaint, the fact that I was so incompetent, so uncoordinated physically, so ungifted musically, meant that all I had to give myself any pride was language. It’s all I had. And the odd thing is that’s all any of us have. It is the miracle of the human species.

The Bat Segundo Show #432: Stephen Fry (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced

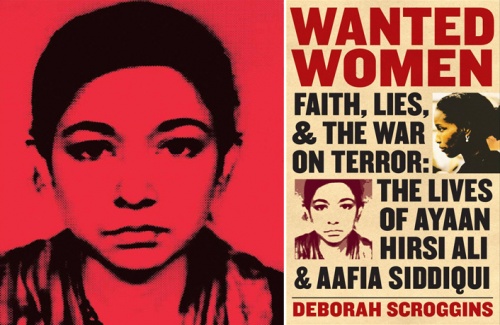

Scroggings: Well, the idea that Islam is responsible for the oppression of women is a very old idea in the West. It goes back hundreds of years. So it’s got a lot of roots here. So when somebody says that, it basically coincides with what people believe. So that’s one reason. I think with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, what really has made her so popular is her incredibly personal story. It’s very inspiring how she tells it. Her coming to the West. Becoming converted to Western ideas. Shaking off Islam. And then being threatened with death for speaking out against it. A lot of people feel very sympathetic to her and feel inspired by her because of that. So I think that’s really why she’s gained such an influential backing. And as to why she got named the 100 Most Influential People, that came right after the murder of Theo van Gogh. And I think it was sort of a sympathy vote on Time Magazine’s part. Because prior to all this, she was a very new junior legislator in the Dutch Parliament. Not somebody who would normally be considered one of the most influential people in the world.

Scroggings: Well, the idea that Islam is responsible for the oppression of women is a very old idea in the West. It goes back hundreds of years. So it’s got a lot of roots here. So when somebody says that, it basically coincides with what people believe. So that’s one reason. I think with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, what really has made her so popular is her incredibly personal story. It’s very inspiring how she tells it. Her coming to the West. Becoming converted to Western ideas. Shaking off Islam. And then being threatened with death for speaking out against it. A lot of people feel very sympathetic to her and feel inspired by her because of that. So I think that’s really why she’s gained such an influential backing. And as to why she got named the 100 Most Influential People, that came right after the murder of Theo van Gogh. And I think it was sort of a sympathy vote on Time Magazine’s part. Because prior to all this, she was a very new junior legislator in the Dutch Parliament. Not somebody who would normally be considered one of the most influential people in the world.