EDITOR’S NOTE: On April 5, 2013, I set out on a twenty-three mile “trial walk” from Staten Island, New York to West Orange, New Jersey, to serve as a preview for what I plan to generate on a regular basis with Ed Walks, a 3,000 mile cross-country journey from Brooklyn to San Francisco scheduled to start on May 15, 2013. This was the third of three trial walks for the project. (And this is the second of a two part report. You can read the first part here.) The collected trial walks represent only a small fraction of what will be created during the national walk. And if we don’t make it to our fundraising goal, then a national investigation of the people, places, and sounds of this country won’t happen. But your financial assistance can ensure that we can continue the Ed Walks project across twelve states over six months. We have two weeks left in our Indiegogo campaign to make the national walk happen. If you would like to see more chronicles carried out over the course of six months, please donate to the project. And if you can’t donate, please spread the word to others who can. Thank you!

Other Trial Walks:

1. A Walk from Manhattan to Sleepy Hollow (Full Report)

2. A Walk from Brooklyn to Garden City (Part One and Part Two)

3. A Walk from Staten Island to Edison Park (Part One)

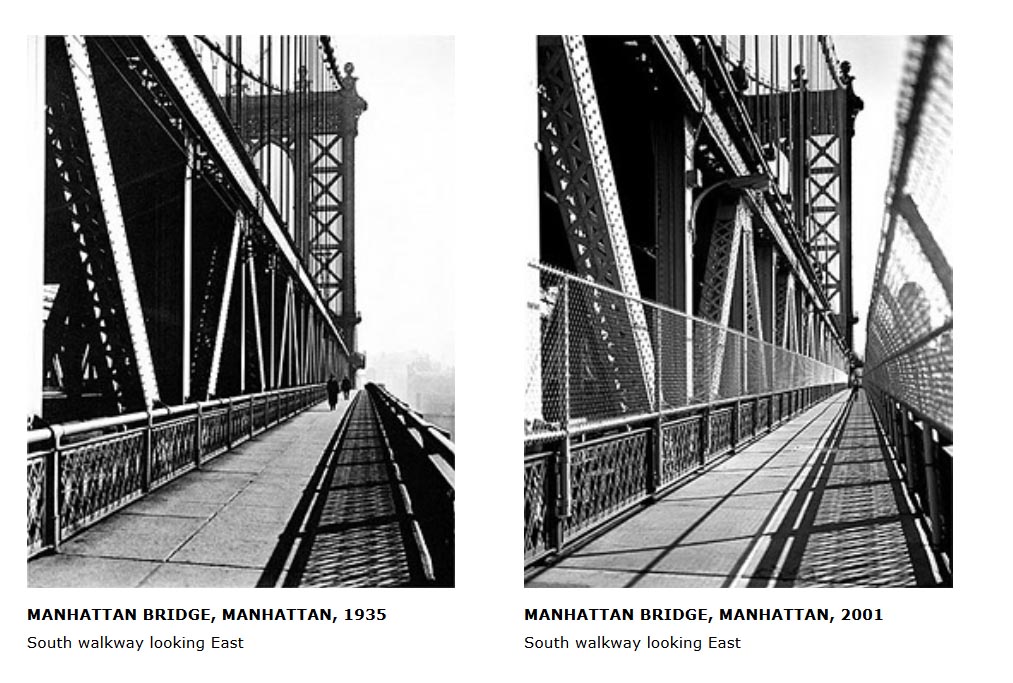

It is so easy to breeze past the grand landmarks in life that we often fail to note how change sneaks up like a drone hovering above a confused moose. The two photos above capture the same view from the Manhattan Bridge walkway, but are separated by sixty-six years. The left photo was taken by legendary photographer Berenice Abbott (who also captured many iconic images of the 1920s Parisian avant-garde community) as part of her groundbreaking project, Changing New York. More than six decades later, photographer Douglas Levere revisited Abbott’s locations at the same time of day and at the same time of year and shot updated stills for his equally exciting project, New York Changing. The right photo is Levere’s. Through one simple act of visual diligence, we see how the unobstructed panorama of the East River has conceded to concerns for safety.

Who put up the chainlink fence? When was it erected? How many leapt to their deaths before the barrier became necessary? If the fence creates an imposed safety that our grandparents never knew, then how has this affected subsequent generations? Do we take fewer risks? Are we as alive?

If Abbott had not taken the photo and if Levere had not been inspired to follow in her footsteps, it’s possible that we wouldn’t be asking these questions. Yet Abbott’s project couldn’t have happened without the Federal Art Project, which helped countless down-on-their-luck artists to excel at their craft and provide inspiring ways of seeing our nation. Seven decades later, crowdfunding is meant to pick up the slack. And while most don’t feel that these investigations into change are as “entertaining” as a new Veronica Mars movie or a $1.2 million Amanda Palmer vanity project that exploits unpaid musicians, we still have to try. It’s our civil responsibility. It’s the legacy we’ll pass to future generations.

When Andres and I hit the Bayonne Bridge and began our carefree stroll across the Kill Van Kull, the Abbott-Levere distinction loomed large in my mind. While I had walked across the George Washington Bridge many times (one time, I confess, to recreate Parker’s march into New York in Richard Stark’s The Hunter), the Bayonne’s guardrail felt more fragile because of its junior height. And as I uploaded photos to Twitter while crossing, there was dubiety from some following along:

@drmabuse that bridge looks worse walking than it does driving (and that says a lot)

— Brian O'Leary (@brianoleary) April 5, 2013

But I’m here to tell you that walking the Bayonne Bridge is a marvelous way of taking in a vantage point unchanged since 1928. Once you get past your modern notions of minimum acme, you swiftly appreciate the tradeoffs: a clear view of dark boats cutting white wakes across gray water, great turquoise gantries in the distance raising their cranes in salute to the sky, the odd toxic beauty of industrial muck mixing it up with water, and rusted platforms awaiting the next raise of the roadway to accommodate the widening of the Panama Canal.

It is possible to appreciate the Bayonne Bridge too much. When Andres and I walked up, I became so excited by the toll plaza’s tight steel boxes and bluish green look that I could not resist taking the above photo. But the marvelous bridge doesn’t receive much in the way of pedestrian traffic. The sour collector working the booth did not take kindly to two cheapskates crossing the bridge for free. I waved and smiled and wished the bitter man a great day. It was the least I could do, seeing as how we were separated by cars and diamond mesh. Andres noted that a Bayonne Bridge toll collector had recently confessed to skimming thousands of dollars. I figured that any unpleasant feelings that the man in the booth developed towards us would be quickly mollified by whatever milk he liked to pour in his coffee. What I did not know was that my salutation was dangerous business.

About a third of the way up the bridge, a Port Authority Police car halted in the middle of the road. There was no siren, but a police officer emerged from the car and called to us. She put her palm into the air, stopping traffic into Staten Island with the strong sovereign touch of a holy man cutting a quirky passage for the Israelites.

She asked who we were, telling me that she was investigating a complaint. I explained who I was and what I was doing with calm éclat. The last thing I wanted was for poor Andres to get arrested. Besides, we hadn’t even hit Jersey yet.

The cars on the bridge couldn’t be held up forever. I provided my name and URL. The police officer seemed satisfied with my explanation. She duly acknowledged that people walk across the George Washington Bridge all the time. All I had to do was vouch for Andres.

I had been holding eye contact with the police officer the whole time. And as I talk up Andres as a dashing young journalist, preparing an exuberant presentation putting forth the thesis that Andres may be the next Gay Talese, I look to my right and see that Andres is smiling, aiming his camera at the police officer.

The police officer did not like this.

I suggested to Andres that he might want to put his camera down. He did this. Andres and I were able to smooth things over, but the police officer kept referring to Andres as a photojournalist.

“Well, he’s really a journalist,” I said.

“He’s got a camera, right? So he’s a photojournalist.”

I figured there were better venues to clarify the distinctions. Several minutes had passed. No car dared beep its horn, although I did see one sullen man waiting for the mess to clear. The officer allowed us to continue our journey across the bridge. A good thing too. Because if Andres and I had been arrested, we would have missed this fantastic boxing mural on the way down to Bayonne:

We arrived in New Jersey, where I swiftly observed the many canted solar panels secured to telephone poles. These were to remain a constant aesthetic companion throughout the walk. I asked one hearty man on his way to work what he knew about the panels, explaining that Andres and I had walked all the way from Staten Island. He was amused by this and told us that the solar panels had been placed on the poles about two years before, intended as a backup power system. I noticed a windmill in the distance.

“Any other questions?” asked the man.

I told him we were fine and thanked him. He directed us to Broadway — Bayonne’s main drag.

We walked past a sign that read “I found Iguana on the street. Please call.” I was curious about the capitalization. Had an actual lizard been located on the street? Or a priapic exhibitionist? Maybe it was someone unimaginative in the sack.

Perhaps it was all the iguana rumination that led us to set foot inside Barney Stock Hosiery Shops — a business devoted to women’s underwear and many other items for nearly a century. Barney Stock proudly announced Spanx in the window, and Spanx was to form a dominant part of my subsequent conversation. Andres and I met Lois and Melissa, the two very vivacious women behind the counter. But they were a bit on the shy side. They didn’t want to be photographed, but they were nice enough to talk about the store’s history.

[haiku url=”http://www.edrants.com/_mp3/tw3-c.mp3″ title=”Conversation with Lois and Melissa at Barney Stock” ]

Lois: Now this one son owns the store. Mel.

Me: Mel.

Lois: Mel Stock. And his father was Barney Stock.

Me: Uh huh. How often do you see Mel?

Lois and Melissa: (together) Every day!

Me: Every day!

All: (laughter)

Me: Wow.

Lois: He comes in every day.

Me: Is he a tough guy?

Lois: Nah. Not really. Well, he has to be to put up with it.

Melissa: To run a business, you’ve got to be tough.

Lois: I’m here 38 years. It will be 39…

Me: Wow!

Lois: It will be 39 next year.

Me: And I didn’t catch your name. What’s your name?

Lois: I’m Lois.

Me: Lois. And you’re Melissa, right?

Melissa: Melissa. Yeah.

Me: So Lois. So you’ve been here for 38 years.

Lois: Yes.

Me: What was your first day like?

Lois: I was in high school.

Me: Oh wow! You were here since high school.

Lois: Well…I left. Got a good job.

Me: You don’t look a day over 35.

Lois: Oh! Yeah.

Melissa: Right! Right! That’s what I say!

Lois: (muttering) I wish I felt a day over 35.

Me: (laughs)

Lois: Anyway, I started when I was in Bayonne High School. I worked here as a junior and a senior. Then I left and got a good job in New York. On Wall Street. Worked there. Then I left there and worked in Western Electric in Newark. Got married. Had three children. And then came back here when my children were in Mount Carmel down the block. And I’ve been here since.

Me: (to Melissa) How about you?

Melissa: Me? Six years.

Me: Six years.

Melissa: I’m not a vet.

Lois: Ha, like Lois is the vet.

Melissa: I’m not a vet at all.

Lois: But it’s a unique store.

Melissa: Very.

Lois: We have everything that you can’t get in any other store.

Me: What’s the most exotic item you have?

Lois: Just bras.

Melissa: Bras and girdles.

Lois: Girdles.

Melissa: Cobblers that nobody can get.

Me: Cobblers?

Lois: Full slips.

Me: You really do have a peach cobbler.

Lois: Eh.

Me: Sorry.

Lois: It sounds good. Anyway, we carry some men’s things too.

Me: A lot of men come in here wanting girdles?

Lois: Some! We can tell who they’re for. But we have to be polite and we do wait on them.

Me: How many units do you move a day, would you say?

Lois: I can’t even ima…every day, it’s different. Now business is slow. Because I think Broadway has changed.

Me: Really?

Lois: We used to have stores from one end to the other. Now it’s all empty.

Me: When did this change or really start to hit? Was it after 2008?

Lois: Yeah. Because they opened a mall over the bridge.

Me: Ah.

Lois: A shopping center. So a lot of stores went down there.

Me: And you guys — are you guys getting by okay?

Lois: Yeah. He owns the building.

Me: Oh, I see. So because he owns, he’s able to…

Lois: Right. He has offices. All upstairs. Yeah.

Me: What do you do to keep a newer set of customers coming in?

Lois: Well, we put in the paper ads, of course. With coupons and, you know, it’s just…Barney Stock is just — we sell Spanx!

Me: Yeah. Spanx is big.

Lois: He sells a lot of Spanx.

Me: (laughs)

Lois: Yes. A lot. And like I say, it’s all the old timers coming back here. People. We do mail orders. Because people move with their children. They’re either down the shore, out-of-state. So they’re so used to what we have that they can’t get any other place. Pantyhose. The end. We do mastectomy bras for women who have had cancer.

Me: Is there a lot of that in this area?

Lois: We get a lot of that too.

Me: I mean, it’s one of the most underdiscussed topics. The fact that there’s just so much cancer.

Lois: Yes.

Me: It really needs to be discussed.

Lois: We specialize in that. We have certified, you know, girls. So we really — if you want something, we have it. Or he’ll find it for you. (laughs)

Me: But Spanx is the big seller.

Lois: Now? Yes.

Me: Has it dropped off at any point?

Lois: No, I think it’s even more.

Me: It’s more.

Lois: So it’s a…I wish you could have met Mel.

Me: You know, I may come back another time. Just to meet Mel at some point.

Lois: Yeah. He’s the sole owner. He had a brother that worked here too. But his brother passed away. So he does it all.

Me: And he’s been here the entire 38 years that you’ve been here?

Lois: Yes. He’s been..

Me: He’s been busting your chops for 38 years? (laughs)

Lois: Right. Nah. He’s a big guy. I get along. I don’t let him bother me. I think that’s why I stay. So I open the store. And he comes in in the afternoon. And then I leave. See ya! (laughs)

Me: Well, thanks very much!

As we continued to walk up Broadway, there were more signs of the economic hits Lois had described. I was saddened to find a rent sign in the window of the Globe Delicatessen. I felt it important to tell Andres that my interest in places like Barney Stock and the Globe Delicatessen wasn’t rooted in nostalgia. I worried about the disappearing connections sustaining community.

Andres and I made efforts to find the To the Struggle Against World Terrorism monument, called one of the world’s ugliest statues by Foreign Policy. But all roads leading to this apparent eyesore were blocked. After a bold nine miles of walking, Andres called it quits. This was a remarkable tally for a man who had never walked across a New York bridge in his life. I saluted him. We said our goodbyes. I headed into Jersey City for lunch.

I regretted skipping over much of Jersey City, but I had no choice. I was behind schedule. It was noon and I was still eleven miles away from West Orange, New Jersey. I had five hours to get to Edison Park before the gates closed.

I did not count on getting screwed by Google Maps.

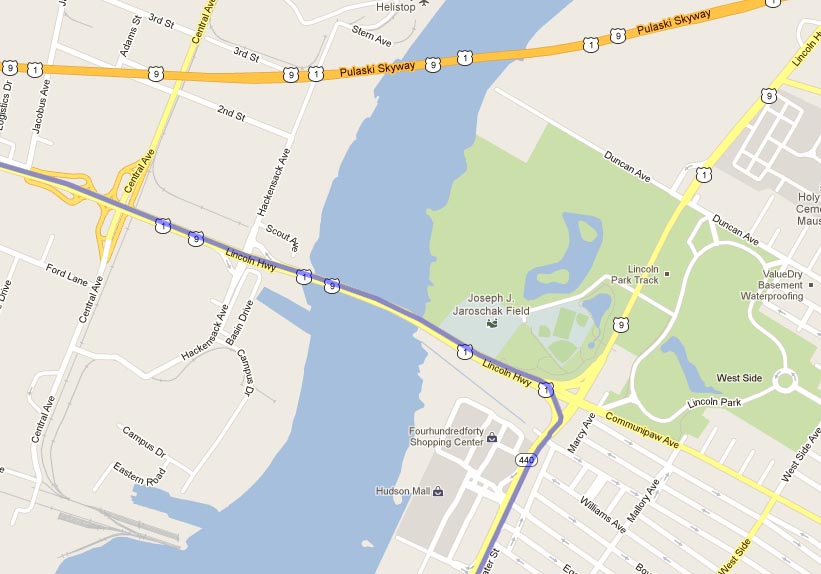

Google Maps claimed that I could simply make a left onto the Lincoln Highway Bridge. But this was a goddam lie. There was nothing at that intersection but asphalt leading up to the bridge. Moreover, despite recent hoopla over an alleged bicycle pathway between Jersey City and Newark, there weren’t any clear signs. I considered asking one of the countless auto dealerships along Communipaw Avenue if they knew anything about this, but I feared that these men would force me to test drive a Hyundai before giving me a straight answer. I wandered around. I discovered a pedestrian overpass which led me over Highway 9 into the western section of Lincoln Park.

When you cross this overpass, you see the Pulaski Skyway in the distance, but there isn’t a single sign suggesting a route for the carless along the Lincoln Highway.

I ended up wasting an hour wandering around the park, looking for the secret passage that would lead me across the bridge. I asked a Jersey City local, but he led me the wrong way north.

I feared that my journey would reach a premature end. I could not find it within me to cheat by thumbing a ride along the Lincoln Highway. I had developed a very clear code of walking ethics. The walking route had to be done completely on foot. I was also worried that I wouldn’t make it to West Orange on time.

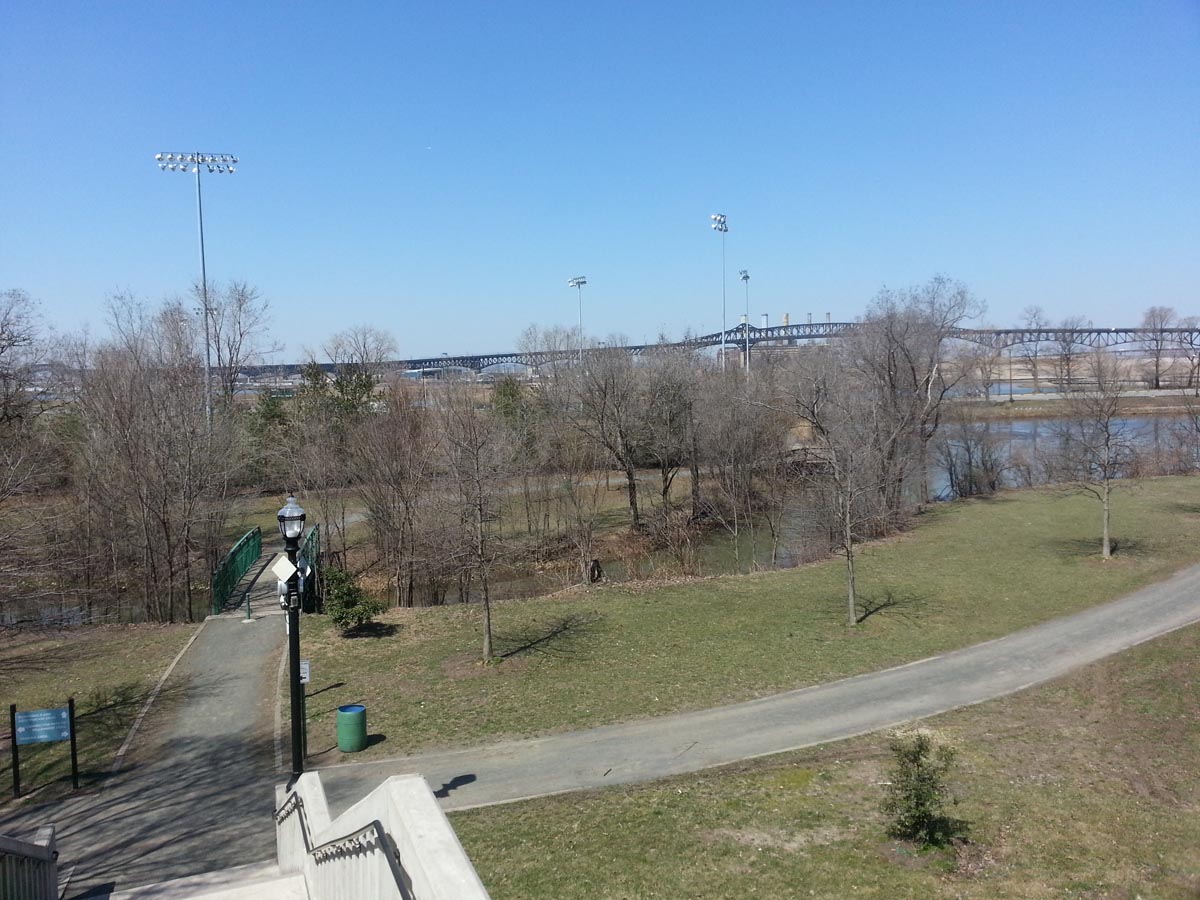

Fortunately, I found the way to the bridge. It turns out that you can walk from Jersey City to Newark once you cross the pedestrian overpass. You have to turn left, walk close to the Lincoln Highway, and follow the path that leads you to the eastern edge of Joseph J. Jaroschak Field. Once you reach the field’s fence, look to your left. You’ll see a modest and unmarked opening leading to a guardrail. Walk through, take a right, and you’ll hug the southwestern edge of the field. You will see this view:

I was so overjoyed to find the way west across the Shawn Carson and Robert Nguyen Memorial Bridge that I considered dancing a jig. Then I realized that the path was more of a consolation prize than a walkway.

Believe it or not, this thin strip on the first of two bridges into Newark is meant to accommodate bicyclists and pedestrians. It’s not too bad. You get a good view of the Pulaski and emerge close to a Jersey truckstop on the other side.

It’s the second bridge that is more problematic.

Between the two bridges, there’s a small sign that directs you to cross to the other side. So you end up walking west on the southbound side, where endless streams of semis bombard you not only with great gusts, but cause a recurrent rattle along this isthmus leading into Newark.

This was easily the shakiest bridge I have ever crossed as a walker. And I don’t recommend it for people who have a fear of heights. Frankly I’m not sure how many people actually use this passage. I didn’t see a single pedestrian or bicyclist along this route. But I did encounter three geese who were wading in sticky industrial mud. I watched a helicopter take off. Construction workers winced at me in bewilderment as I walked the little-tread path. But I made it into Newark, albeit an area of Newark that wasn’t designed for pedestrians.

I walked under overpasses with foul detritus strewn along any surface that was not road and passed trucks lodged into deep dirt beds. I walked by an abandoned movie multiplex, where a mysterious man on a yellow motorcycle swirled around a parking lot in disrepair. After two or three miles of this, I discovered civilization in the form of streets named after presidents.

I had developed a theory that a strawberry ice cream cone would carry me into Edison Park. I made it to Nasto’s, but there wasn’t a place to sit. This was just as well, because there was very little time. I had only a few hours to huff it through Newark into the Oranges. Six miles in two hours and much of it uphill. There was a great deal I had to pass over. So I offer considerable contrition to Newark. Alas, the U.S. National Park Service keeps very strict hours.

I got to Edison Park at 4:40 PM. Twenty minutes to spare. The mighty water tower loomed above me. Now it was a question of getting into the lab.

I walked to the door. It was locked. So were all the surrounding buildings. I circled around the lab and peered into foggy windows, wondering if I had a chance to visit it after a twenty-three mile walk. That’s when I saw the ranger.

[haiku url=”http://www.edrants.com/_mp3/tw3-d.mp3″ title=”Conversation with Carmen at Edison Park” ]

Not only was Carmen kind enough to unlock the chemistry lab and permit me to see the test tubes and beakers and surfaces that haven’t shifted their position in decades, but he also agreed to a quick interview.

Carmen has worked as a ranger for three years and very much enjoys the job. Edison Park is the only place he’s ever toiled as a ranger. Before he was a ranger, Carmen worked for the military for 21 years performing aircraft maintenance.

To my great astonishment, one doesn’t have to pull any strings to get a job at Edison Park. If a job becomes available, one simply applies. There’s no need to dredge up esoteric facts, such as the mysterious five dot tattoo on Edison’s left forearm, to get the job. Carmen says he knew a bit about Edison in advance, but Edison Park’s crackerjack staff has been doling out biographical details for quite some time.

“It’s amazing how much you learn as soon as you come here,” says Carmen. “The books you read, the interaction with the other park rangers that are here, the curators, the archivists. You really start to learn an awful lot. I was by no means an expert at Mr. Edison. But as you work here and you are ingrained in this and immersed in this, you start to pick up and learn a whole lot about what’s going on.”

I asked Carmen if the public ever asked him unusual questions. He told me that many people ask if Edison’s house and lab are haunted: an unusual inquiry, given Edison’s commitment to science. People also want to know about Edison’s height. It turns out that Edison stood five foot seven, which matches Carmen’s height. Part of me wonders if there’s some subconscious employment requirement among the National Park Service to hire Edison Park employees who stand as tall as the namesake.

I challenge Carmen’s commitment to Edison by pointing out how the inventor ripped off people like Nikola Tesla and Joseph Swan.

“Well, that’s more of a misconception,” he replies.

“You’re going to defend the man.”

“I’m definitely going to defend the man.”

“Well, you work for Edison Park.”

Carmen points out that Thomas Edison had 1,093 patents, more than any other figure in U.S. history.

“You think about all these 1,093. The incandescent lightbulb and the rechargeable battery. Movies. I mean, other people have all worked on that before. But his really true invention, the only invention that he really came up with, was really the phonograph. Nobody had ever recorded voices before. So you gotta look at Mr. Edison not so much as this great inventor, but as a great innovator.”

This is my final trial walk for this project. I have traveled north to Sleepy Hollow, east to Garden City, and west to West Orange. I hope that these trial walks have demonstrated my good faith, my endurance, and my limitless curiosity.

There is now one long stretch for me to walk. And I cannot do it without your support. It will take six months. It will help create a portrait of this country. This is an all-or-nothing proposition. But I believe we can do it. If you have enjoyed these reports, please donate to the project today. Thank you.

Correspondent: Going back to the issue of preparation, perhaps you can talk about it in light of this particular movie. I’m curious if there is such a thing as overpreparation for you. For a performance like this, for a performance elsewhere. Where if you plan something too much, then you’re going to lose the spontaneity, you’re going to lose the naturalness of human behavior, and the like.

Correspondent: Going back to the issue of preparation, perhaps you can talk about it in light of this particular movie. I’m curious if there is such a thing as overpreparation for you. For a performance like this, for a performance elsewhere. Where if you plan something too much, then you’re going to lose the spontaneity, you’re going to lose the naturalness of human behavior, and the like.