Sarah Wendell and Candy Tan appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #296.

Sarah Wendell and Candy Tan are most recently the authors of Beyond Heaving Bosoms. They are also the proprietors of Smart Bitches, Trashy Books.

Subjects Discussed; Kathleen Woodwiss’s The Flame and the Flower, the beginnings of original paperback romance, genre respectability, romance’s profitability, the stigma of effeminacy, cozy mysteries, arterial bloodspray, the fallacious anatomical placement of the hymen, spontaneously lactating virgins, whether the pun is intended or not, editorial house style and “the magic hoo hoo,” the wandering vagina, Lilith Saintcrow’s “Half of Humanity is Worth Less Than a Chair,” rapists within romances, Candy Tan’s suggestive hand gestures, marriage and choice, intrusive Mercedes drivers and related invective, the frequency of oral sex within romances, how far sex needs to go in art, porn, anal sex, bukkake, double wangs and double penetration, homunculi, the line between romance and erotica, hypothetical genre fusion, poseur man titty and erotic romance, the “shop and run” approach to romances, embarrassing covers, dashing long-haired heroes and bald badasses, game theory and Sarah and Candy’s reading preferences, Candy’s pirate fixation, the sharp disparity between genuine smelly pirates and the twee McSweeney’s pirates, “the big mis,” John O’Hara’s Appointment in Samarra, misunderstandings and character flaws, simultaneous organs, romances and Republican presidencies, Cassie Edwards and plagiarism, and encouraging civil disagreement and discourse in the romance community.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: Science fiction, mystery, YA. These genres are getting respect, particularly in the last decade. And yet romance is still one of those things in which people thumb their noses down. Why do you think this is? Must we always have some place to go for the ghetto? What’s the deal here?

Correspondent: Science fiction, mystery, YA. These genres are getting respect, particularly in the last decade. And yet romance is still one of those things in which people thumb their noses down. Why do you think this is? Must we always have some place to go for the ghetto? What’s the deal here?

Sarah Wendell: Well, I will point out that romance is actually getting a lot more respect because of the turgid strength of its quarterly earnings. And even though most industries — especially in New York, which is hyper-navel gazing in the financial industry — are experiencing massive losses year to year and quarterly to quarterly, romance is the one erect column in your spreadsheet. And it remains quite strong. So while it doesn’t get a lot of respect from your average cocktail crowd, most financial newspapers are having to pay attention to the strength of romance when you’re looking at it as an investment, or as an indicator of an economy. Which is why I think that Harlequin is chuckling, or befuddled, at the entire economic crisis. Because they were founded during the Depression. I’m sure they’re looking at this, going, “This? This is nothing. Are you kidding? Let me just tell you what it was really like.”

Candy Tan: This is great for business!

Sarah Wendell: I know.

Candy Tan: What the hell? No, I think personally that a lot of the reason why romance novels are the Rodney Dangerfield of genre fiction is the stigma of effeminacy. You know, science fiction. They’re “novels of ideas.” Mysteries have lots of blood and guts. Well, some of them do. The ones that don’t get respect, interestingly enough, tend to be the cozy mysteries. The ones in which there’s a cat solving the goddam murder or whatever the hell. You know, those are the ones: “Oh man, they’re not worth taking seriously.” If I remember correctly, and I might be wrong, because I don’t know mystery as well as I should, the hardboiled mystery were one of the first to exit the ghetto.

Sarah Wendell: As long as there’s arterial bloodspray, you get some respect.

Candy Tan: Or you know…

Sarah Wendell: Spooge, not so much.

Candy Tan: Yeah, there’s definitely a lot more respect for male fantasies versus female fantasies in fiction and you see this over and over again.

Correspondent: If we’re going to talk about arterial bloodspray, I think we should point to the fallacious anatomical scenario involving hymens, which you point out in this book.

Sarah Wendell: At length. At great, great length.

Correspondent: Yeah, at great length.

Sarah Wendell: You can tell that this is something that rubbed us the wrong way.

Sarah Wendell: You can tell that this is something that rubbed us the wrong way.

Correspondent: Yes, I got the sense…

Sarah Wendell: And to anyone who’s listening, I want a complete pun count at the end of the podcast. And if we can get an accurate pun number, I’ll totally give away a copy of the book and some beaucoup prize if you can identify how many puns we make in the course of this interview.

Correspondent: But the question is: You have so much attention to detail in historical romance and yet this one thing continues to propagate, continues, I suppose, to not be patched up in quite the way that one would expect.

Sarah Wendell: Good one.

Correspondent: And so what I’m wondering is: Do you think romance readers and romance writers want to fantasize about where the hymen is?

Sarah Wendell: No, I think it’s simple oral history. And I don’t mean that in a bad way. I think that the legend of the misplaced hymen is just something that’s passed down from writer to writer. Much like the historical inaccuracies that plague other parts of the specific historical genre, “Where the hell your hymen is?” is one of them.

Candy Tan: Here’s the thing. I think I’ve spotted the same misplacement of the hymen in other books. Not romance novels. I think I’ve read a couple of horror novels — and maybe it would have made sense if the girl being devirginized were some kind of filthy alien beast. By hymen, you mean vagina dentata. But you don’t. Oh, oh, it’s infected other genres too! How wonderful! Anatomical craziness all the way around.

Sarah Wendell: And that’s not the only anatomical inaccuracy we’ve discovered. There’s a few one off inaccuracies we’ve discovered that are just mind-boggling. Like there’s one Gaelen Foley where the heroine’s a bona-fide virgin. And I mean bona-fide. Not is she like a virgin, but she’s like a princess or some shit? They haven’t even had sex yet. This is the first time they’re kissing in the woods. And he tastes her milk. Because, you know, virgins spontaneously lactate. Like a postpartum woman going into Target and hearing a baby cry. Yeah, same thing.

Candy Tan: It was the most nipple-tacular moment in all historical romance.

BSS #296: Sarah Wendell and Candy Tan (Download MP3)

Listen: Play in new window | Download

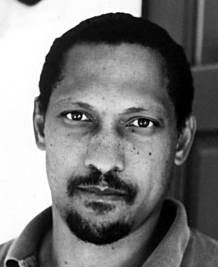

Correspondent: I recently read Richard Powers’s forthcoming novel, Generosity, which deals with the notion of what a novel really is and what ideas and characters really are. And I’m very curious to put this question to you. To what degree do you need reality to start from? And to what degree do you feel the need to be faithful to reality? Or even faithful to real-life figures? Or can you accept a Percival Everett figure in this who also happens to have a book called Erasure?

Correspondent: I recently read Richard Powers’s forthcoming novel, Generosity, which deals with the notion of what a novel really is and what ideas and characters really are. And I’m very curious to put this question to you. To what degree do you need reality to start from? And to what degree do you feel the need to be faithful to reality? Or even faithful to real-life figures? Or can you accept a Percival Everett figure in this who also happens to have a book called Erasure?

Correspondent: I should probably start this conversation off by confessing something to you. I think that Rachael Ray is a bit on the crazy side. She’s not someone who really makes me comfortable. I’m actually quite frightened by her. You know, I don’t find her down-to-earth at all. And I think maybe we can start off by describing how we went from this relatively benign cooking show setup, in which you had a quieter, less frenetic impulse, to this more exhibitionistic cooking show that involves a Jerry Springer-like audience shouting for the EVOO and all that. How did we get from one extreme to the other? Do you have any fundamental observation throughout the course of your meticulous observations?

Correspondent: I should probably start this conversation off by confessing something to you. I think that Rachael Ray is a bit on the crazy side. She’s not someone who really makes me comfortable. I’m actually quite frightened by her. You know, I don’t find her down-to-earth at all. And I think maybe we can start off by describing how we went from this relatively benign cooking show setup, in which you had a quieter, less frenetic impulse, to this more exhibitionistic cooking show that involves a Jerry Springer-like audience shouting for the EVOO and all that. How did we get from one extreme to the other? Do you have any fundamental observation throughout the course of your meticulous observations?

Correspondent: I must ask then, Mara Faye, if you had read any other books to get the idiom right in English for this. Because both your translation of this book [Wonderful World] and your translation of Pandora in the Congo strike me as far more specific. It’s almost as if the translation itself can be placed within a neat, genre-specific feel in the prose. And I’m curious if you do it more intuitively or if you actually do, in fact, try and read books surrounding a particular genre or a particular place it might end up. So that it might be more palatable to the English ear.

Correspondent: I must ask then, Mara Faye, if you had read any other books to get the idiom right in English for this. Because both your translation of this book [Wonderful World] and your translation of Pandora in the Congo strike me as far more specific. It’s almost as if the translation itself can be placed within a neat, genre-specific feel in the prose. And I’m curious if you do it more intuitively or if you actually do, in fact, try and read books surrounding a particular genre or a particular place it might end up. So that it might be more palatable to the English ear.

Correspondent: If we’re talking about time, there’s also the notion of reader’s time. And as a stylist, you have some control over how frequently or how long or how short the reader’s going to turn the page. When I read your book, I found numerous passages when I would slow down. And then when dialogue would bump up, particularly with the scenes with the cop, it then sped up.

Correspondent: If we’re talking about time, there’s also the notion of reader’s time. And as a stylist, you have some control over how frequently or how long or how short the reader’s going to turn the page. When I read your book, I found numerous passages when I would slow down. And then when dialogue would bump up, particularly with the scenes with the cop, it then sped up.