Jennifer Weiner is a best-selling author. And while her latest novel, Best Friends Forever, proved popular enough to hit #1 on the New York Times bestseller list, this didn’t stop a Barnes & Noble bookstore in Framingham, Massachusetts from raising a censorious eyebrow.

Some bookstores have begun instituting informal policies which preclude authors from using four-letter words during a public reading. And even dependable draws like Weiner are being asked to hold their tongues. These developments — reflected most recently in the Weiner case — raise new questions about just how much an author is allowed to get away with in the 21st century and whether bookstore policies that are understandably intended to protect children are going too far.

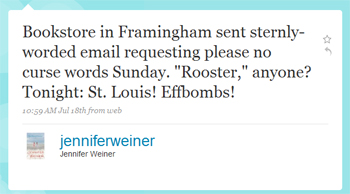

The trouble for Weiner began when she playfully announced the “potty-mouthed” nature of her Best Friends Forever book tour on Twitter. Shortly after her Philadelphia reading, Weiner later tweeted that she had received a warning:

Weiner carried on with the Framingham gig without setting off any F-bombs, and applied her saucy language instead to the inscriptions. (After tweeting about the Framingham event, the organizer of a subsequent off-site event in St. Louis encouraged Weiner to be extra raunchy.)

“I can’t imagine it’s a blanket B&N policy,” said Weiner. “I kicked off the Best Friends Forever tour at the Barnes & Noble in Lincoln Triangle in New York City, and I said ‘cock’ like nine times and told a story about a Hitachi Magic Wand, and the manager seemed perfectly okay with it (my poor editor, who brought her parents to the reading, not so much). As much as I’d like to turn this into a ‘corporate stiffs censor freewheeling lady writer because the world hates it when a lady succeeds’ story, I honestly think it was just this one bookstore, that one afternoon, making a not-unreasonable request.”

A list of questions was sent to Mary Ellen Keating, Barnes and Noble’s senior vice president of corporate communication and public affairs. But there was no response. I was able to reach Margaret Moore, the community relations manager of the Framingham store, by phone. But she was extremely nervous, even when I assured her that I was merely determining questions of policy. I did receive a return phone call from Maddie Hjulstrom, a regional community relations manager at Barnes and Noble, who was gracious enough to talk with me.

Hjulstrom informed me that the email had been sent by Moore when Moore had “learned that Ms. Weiner’s language was colorful at her discussions.”

According to Weiner, the Framingham controversy arose out of concerns that the reading area was adjacent to the children’s section and that Weiner’s scheduled reading time — 3:00 PM — would be too early to account for the hallowed ears of tots.

“Because the event was on a Sunday afternoon,” said Weiner, “I think the bookstore managers reasonably expected that there would be kids there, and felt that they could reasonably ask me to tone down the cussing.”

This was confirmed by Hjulstrom, who told me that the objections had to do with the microphone’s close placement to the children’s department and the possibility that Weiner’s amplified words might drift like cigarette smoke into a 1980s restaurant’s nonsmoking section.

“We want to be respectful of young families and children,” said Hjulstrom. “We don’t regulate where children are in our store. At 3:00 PM, it might be a problem.”

Had Barnes & Noble ever received any customer complaints because of an author or a poet using salty language during a reading? Hjulstrom told me that she couldn’t give me an example of the Framingham store having received a single customer complaint, but that the region, as a whole, had received a few complaints.

The Barnes & Noble “no salty language” policy is, according to Hjulstrom, “not a written policy, just common courtesy.” It is something that is determined on a case-by-case basis.

“All we can do is ask,” said Hjulstrom. “We don’t enforce. We don’t kick them out of their store. We just ask them to respect the children who are in the stores.”

I asked Hjulstrom what might happen if an author used salty language, but did not receive a single customer complaint.

“I’m not comfortable going into what ifs,” replied Hjulstrom. “I just want to deal with the facts.”

But the prohibition causes one to wonder why bookstores — even with the possibility of a child lurking around a bookstore late at night — would be so offended by a monosyllabic exclamation that anyone who has ever stubbed a toe is quite familiar with. Were there efforts by Weiner and Barnes and Noble to broker a last-minute deal?

“We didn’t try to broker a compromise mostly because there wasn’t time,” explained Weiner. “The best solution would have been either to hold the event somewhere else, or after dark, and with just over twenty-four hours, on a weekend, to either reschedule or relocate, that just didn’t seem feasible. And again, once I got over my reflexive ‘the MAN is trying to SHUT ME UP’ paranoia, it didn’t seem like a crazy thing to ask. I’ve got little kids, and if I took them into a bookstore on a Sunday afternoon to pick up the latest Sandra Boynton or ‘Junie B. Jones,’ I probably wouldn’t be thrilled to find some lady standing behind a microphone talking, as I tend to, about ‘wall-to-wall cock.'”

Still, independent bookstores such as San Francisco’s The Booksmith have conducted numerous author events in its children’s section, closing the section off to make room for the audience to sit down. Booksmith co-owner Praveen Madan informed me that, while there are generally no kids around at the time of the event, his bookstore doesn’t make any concessions if an event takes place in the middle of the day.

“We take freedom of speech very seriously and even the suggestion of us laying down any kind of censoring guidelines for authors makes me cringe,” said Madan. “And the issue here is more than freedom of speech. We believe it’s important for authors to be authentic and credible, and sometimes being authentic requires saying things that might end up offending some people. I would rather shut down the bookstore and sell falafels than try to engineer an author’s talk to make the author more palatable for a certain audience. You should be clear about what business you are in. We are in the business of intellectual discourse and opening people’s minds to new ideas and possibilities. If you want to be in the business of reinforcing people’s existing belief systems, than you should run a religious institution or radio talk show, not a bookstore.”

It’s also worth observing that prohibitions on what an author can say at a reading can sometimes have unexpected side effects. As Tayari Jones observed on her blog recently, the author can feel oddly shamed when contending with a complaint.

Jessica Stockton Bagnulo, formerly of McNally Jackson and now working hard to open the Greenlight Bookstore in Fort Greene this autumn, says that there was never a policy prohibiting language or controversial topics at an author event when she worked at McNally. But she did mention that she hoped to be more sensitive to such matters at Greenlight.

“We don’t intend to set any blanket policy,” said Bagnulo. “I think for the most part we will trust our customers to know whether an author is going to be inappropriate for their children or potentially offensive to their own sensibilities. As long as we make clear from the outset what the event is likely to contain, we won’t try to restrict or prohibit authors from anything they’d like to say.”

Even if the event is scheduled in the middle of the day?

“Not unless it’s an event specifically geared toward kids,” replied Bagnulo. “For example, at McNally we held a Halloween event that had kids programming earlier in the day, and some adult authors reading later that had lots of graphic blood and gore.”

Before the Framingham incident, Weiner had never received any complaints from a bookstore for her act. But censorship issues aren’t limited to the big box stores. Weiner alluded to an incident that came from an ostensible independent:

“In 2001, when Good in Bed came out, I did hear from one independent bookstore somewhere in the Midwest that an older gentleman had objected to a cover featuring the book’s poster (naked legs and cheesecake) in the window. But that’s as close to censorship as I’ve come.”

For what it’s worth, Weiner did say that she would do an event at the Framingham bookstore again: “I’d just make sure it was an evening event, or that it was held somewhere far, far away from the innocent ears of children.”

“In general, we feel that authors these days have become rather conservative and risk averse because they are trying to become bestsellers and are afraid of stirring controversy,” said Madan. “I wish more authors would pick topics that might be controversial and not worry about offending people. There are important topics being ignored and we all tend to surround ourselves with people we agree with and we like.”

“I think that indie bookstores work to create an environment of mutual respect between authors and audiences,” said Bagnulo, “where what is controversial is taken in context as part of the conversation, and there’s enough transparency of intention that people are unlikely to be offended.

“It’s not a bad idea to mention ahead of time, ‘Hey, I work blue,'” said Weiner, “but it’s never been a problem in the past, and I don’t really expect it to be a problem going forward.”