Alison Bechdel recently appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #250.

Ms. Bechdel is most recently the author of The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For. To listen to our previous interview with Ms. Bechdel, check out The Bat Segundo Show #63.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Overly concerned with modifiers attached to artists.

Author: Alison Bechdel

Subjects Discussed: The relationship between visual developments and storyline developments, how personal developments worked their way into Dykes to Watch Out For, Tips o’ the Nib, narrative authenticity, research through asking people, being afraid of the telephone, the comics world as a simulacrum of the real world, being overly stimulated by the real world, developing specific background details, the risks of diverting attention between graphic novels and comic strips, dwelling upon a community vs. dwelling upon the self, therapy, Woody Allen, being ahead of the technological curve, Proust and the first telephone call in a novel, laziness vs. being seduced by technology, scanned lettering, managing all the characters in the strip, having characters refer to each other by first name, the advantages and disadvantages of deadlines, adapting media messages for the comics medium, Mad Magazine and Mort Drucker, fear of empty space, when text and images are not enough for comics, political semiotics and behavior, strips with little to no dialogue, artistic influences, fitting multiple people into a frame, portraying the butts of various characters, contending with censorious requests from newspaper clients, the limitations of four rows, Madwimmin Books and big box stores, why the bookstore is the perfect social nexus, the outcry upon introducing Stuart, the ideological balance between Mo and Stuart, gender jokes as cheap shots, contending with those who didn’t understand Bechdel’s storytelling style, the role of politics in Dykes, the moral responsibilities of a cartoonist, and Proposition 8 and the future of cartooning.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I think we should really clarify this for the record. I mean, the stripes on Mo’s shirt become more pronounced over the course of time. And they increasingly grew thicker during the course of the early ’90’s. And then sometime around 1995, they solidified into that absolute thickness that we have enjoyed for the last decade or so. I know there have been many Harry Potter jokes that you’ve thrown around. But you were there, of course, before Harry Potter.

Correspondent: I think we should really clarify this for the record. I mean, the stripes on Mo’s shirt become more pronounced over the course of time. And they increasingly grew thicker during the course of the early ’90’s. And then sometime around 1995, they solidified into that absolute thickness that we have enjoyed for the last decade or so. I know there have been many Harry Potter jokes that you’ve thrown around. But you were there, of course, before Harry Potter.

Bechdel: That’s right.

Correspondent: But I have to ask you about the stripes. Had it occurred to you at any time to have Mo not wear a striped shirt? Or did you feel that this was such an indelible part of her disposition?

Bechdel: I think there might be one scene where she’s not wearing a striped article of clothing. But I can’t remember what it is or what its significance is. Indeed, the stripes did grow thicker. Very good observation!

Correspondent: Yeah! They did! They did! It was really great to read this all in one burst, because there are so many different character developments, which I plan to ask you about. But maybe I could probably phrase this better by pointing out Sparrow, for example. How the front curls that she had were chopped off to fit in with the adjusting times. And I’m wondering when you decide to change the look of a character. What circumstances dictate that? And some characters, of course, like Mo, stay the same over the course of time.

Bechdel: Wait, can I just make an observation? Thinking about those thickening black stripes, I think that’s of a piece with the increasing darkness of the strip and indeed the era in which it was passing through.

Correspondent: Yeah, yeah, that’s true.

Bechdel: Maybe now if I were continuing to write it, Mo’s stripes would continue to get thinner and thinner.

Correspondent: Thinner, thinner, thinner.

Bechdel: No, I mean literal — I mean like figurative darkness.

Correspondent: Figurative darkness!

Bechdel: Yeah! Yeah!

Correspondent: So there’s some allegory here, I see. So it’s

Bechdel: Yeah, I’m totally bullshitting. I’m totally making this up.

Correspondent: Ah! No, no, this is good. This is good.

Bechdel: But…

Correspondent: But we can give the listeners something to latch onto here. Great allegorical decisions upon your part. I mean, how much of this is intuitive? And how much of this is really a conscious effort? Well, you know, Mo’s stripes look better. They just look better.

Bechdel: No, it was purely a visual decision. I don’t know. I just used a different pen or something. And it looked better thicker.

Correspondent: Okay, what about Sparrow’s hair?

Bechdel: Sparrow’s hair. Well, what made me decide to do that? I don’t know, but interestingly it prefigured her crossing over from being a lesbian into being a…

Correspondent: Yeah.

Bechdel: …a bisexual. I forget what she called herself. A bisexual lesbian.

Correspondent: I think she did.

Bechdel: But she didn’t want to completely let hold of her lesbian title. But she got this slightly more feminine-looking haircut.

Correspondent: Yeah, she did. She did. I mean, did you plan her to essentially shack up with Stuart?

Bechdel: No, not at that point. I didn’t.

Correspondent: How much does a visual decision like this predate the actual plotting? Or perhaps anticipate it in some way? It’s a very interesting observation.

Bechdel: It is interesting. What’s even more interesting is that the way that these storylines and developments prefigure my own life. Or are a reaction of things going on in my own life. Which I don’t like to admit, typically. But as I looked back over the book, I could see all these absurd parallels with my own life. It seemed almost indiscreet to have included them.

BSS #250: Alison Bechdel (Download MP3)

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Correspondent: I wanted to also ask about the use of white space, and often the lack of white space, with some of the panels that have this extraordinarily long rant that one of the characters is conducting versus using the clip art and shifting it to the right hard edge of the panel or the left hard edge of the panel, or what not. What is your criteria in terms of white space and filling up the panel? Is it contingent upon the words you have to deliver for any particular strip?

Correspondent: I wanted to also ask about the use of white space, and often the lack of white space, with some of the panels that have this extraordinarily long rant that one of the characters is conducting versus using the clip art and shifting it to the right hard edge of the panel or the left hard edge of the panel, or what not. What is your criteria in terms of white space and filling up the panel? Is it contingent upon the words you have to deliver for any particular strip?

Correspondent: I wanted to also talk with you about your “Family History” strip. I mean, it’s probably the closest thing in this collection to a hip-hop montage. You have, of course, the many births with the common images. A mother — one of your ancestors — giving birth with the “UNNNNH!” And you have a marriage with the “I do.” The swathed baby who is being held up by the white hands. And the like. I wanted to ask why repetitive images, or a hip-hop montage, seemed the best way to approach your own particular past.

Correspondent: I wanted to also talk with you about your “Family History” strip. I mean, it’s probably the closest thing in this collection to a hip-hop montage. You have, of course, the many births with the common images. A mother — one of your ancestors — giving birth with the “UNNNNH!” And you have a marriage with the “I do.” The swathed baby who is being held up by the white hands. And the like. I wanted to ask why repetitive images, or a hip-hop montage, seemed the best way to approach your own particular past.

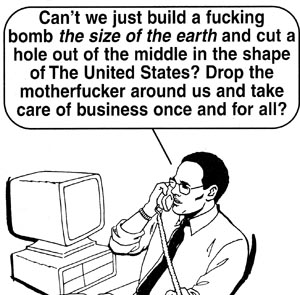

In the comic, Gibson is an unlikable narrator, who lacks the subtlety of another unlikeable narrator Millar wrote — Nazi Major Bauman in “Prisoner Number Zero,” which is one Millar’s best Wolverine stories. In Wanted, Gibson says, “I didn’t realize how much I hated the human race until I had the fuckers swanning around between my crosshairs.” This narration isn’t particularly antagonizing to the reader, but Gibson’s jokes about Down syndrome and babies born with spina bifida may be. Perhaps lazily, Millar titled the second issue, “Fuck You,” a charming name when considering some of the stale comic book in-jokes: in one scene, Mr Rictus, the super-supervillain (what do you call the villain in a story about supervillains?), kills the parents but spares their child, saying, “Leave him. With any luck, he’ll spend the next eighteen years training himself to avenge these idiots and give me someone interesting to fight when I’m an old man.”

In the comic, Gibson is an unlikable narrator, who lacks the subtlety of another unlikeable narrator Millar wrote — Nazi Major Bauman in “Prisoner Number Zero,” which is one Millar’s best Wolverine stories. In Wanted, Gibson says, “I didn’t realize how much I hated the human race until I had the fuckers swanning around between my crosshairs.” This narration isn’t particularly antagonizing to the reader, but Gibson’s jokes about Down syndrome and babies born with spina bifida may be. Perhaps lazily, Millar titled the second issue, “Fuck You,” a charming name when considering some of the stale comic book in-jokes: in one scene, Mr Rictus, the super-supervillain (what do you call the villain in a story about supervillains?), kills the parents but spares their child, saying, “Leave him. With any luck, he’ll spend the next eighteen years training himself to avenge these idiots and give me someone interesting to fight when I’m an old man.” The Ultimates embraced a decompressed narrative – what Millar called novelistic – where characters didn’t appear in every issue, and the plot developed at a pace that strengthened suspension of disbelief; Millar and Hitch created a superhero story that reads as how it would really happen. The decompressed narrative was hardly the revolution Millar claimed it was in commentary of the first volume of the series, but a style characteristic that made The Ultimates distinct from the typical mainstream superhero book. Millar set the series in today’s pop culture world, dropping references to Shannon Elizabeth, Jennifer Tilly, President Bush, Samuel L. Jackson, Johnny Depp, and Robert Downey Jr. (Downey was used in a joke about drug use.) Millar also addressed U.S. politics as the country fought its “War on Terror” and its war in Iraq. Thor resists working for the U.S.-backed Ultimates team because of the country’s military operations and oil obsession. When Thor complains to Nick Fury about the U.S. negotiating with the terrorists, Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch, Fury says, “Ain’t the first time the security services done deals with terrorists, big man.” Millar risked alienating readers who did not agree with his politics, though it’s unlikely he cared. The aforementioned Frank Miller and Alan Moore commented on politics in their most famous superhero stories.

The Ultimates embraced a decompressed narrative – what Millar called novelistic – where characters didn’t appear in every issue, and the plot developed at a pace that strengthened suspension of disbelief; Millar and Hitch created a superhero story that reads as how it would really happen. The decompressed narrative was hardly the revolution Millar claimed it was in commentary of the first volume of the series, but a style characteristic that made The Ultimates distinct from the typical mainstream superhero book. Millar set the series in today’s pop culture world, dropping references to Shannon Elizabeth, Jennifer Tilly, President Bush, Samuel L. Jackson, Johnny Depp, and Robert Downey Jr. (Downey was used in a joke about drug use.) Millar also addressed U.S. politics as the country fought its “War on Terror” and its war in Iraq. Thor resists working for the U.S.-backed Ultimates team because of the country’s military operations and oil obsession. When Thor complains to Nick Fury about the U.S. negotiating with the terrorists, Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch, Fury says, “Ain’t the first time the security services done deals with terrorists, big man.” Millar risked alienating readers who did not agree with his politics, though it’s unlikely he cared. The aforementioned Frank Miller and Alan Moore commented on politics in their most famous superhero stories. Millar has conquered one mainstream, and could conquer the larger one. His new series with John Romita Jr.,

Millar has conquered one mainstream, and could conquer the larger one. His new series with John Romita Jr.,