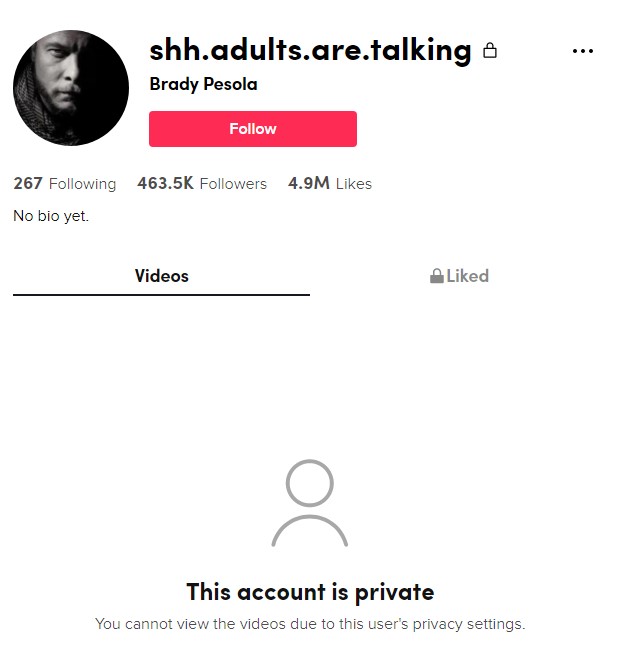

This morning, I learned that my TikTok account was permanently banned. Why? Because I spoke out against the misogynistic TikTok user Brady Pesola, who goes by the handle @shh.adults.are.talking.

Pesola specializes in a type of repugnant hypermasculine sexism that has netted him nearly half a million followers. His ugly formula of speaking in a tenth-rate John Wayne swagger and casually demeaning women for their feelings and their thoughts has proven such an alluring draw that he has been able to parlay this into a sizable fan base. I had responded to one of Pesola’s slightly less sexist posts in which he boomed, “Stop being an insecure little bitch and grow up,” by pointing out, quite calmly, that being emotional was not a sign of insecurity. For this, Pesola singled me out as “unhinged,” prefacing his stitch by saying “This one’s extra spicy.”

I was then bombarded by numerous comments from Pesola’s followers and later had my account hit with false reports of bullying and harassment, after I proceeded to outline the full extent of Pesola’s misogyny in a series of videos. And I received a permanent ban. I have tried to appeal this ban, but I have heard nothing from TikTok. The message is clear. TikTok supports the misogyny of creators with huge followings rather than the small-time people who speak out against such vile strains. I also suspect that I was targeted by TikTok because a few of my anti-corporate and pro-union videos went viral. Since I cannot access my videos, this article represents a thorough effort to expose and document Pesola’s clear hatred of women, as well as TikTok’s willful advocacy of misogyny among its high-ranked creators, despite community guidelines declaring that hateful behavior directed towards a group is prohibited. A thorough review of Pesola’s TikTok feed reveals that he violated these rules multiple times and faced no consequences — aside from a 24 hour ban in December 2020 and a permanent ban for twenty minutes that was somehow removed this month. Apparently, if you have enough followers on TikTok, you can get away with saying anything. The rules don’t apply to those who have the clout.

Pesola, a former Marine based in the San Diego area (originally from Minnesota) who runs a dubious nonprofit operation known as the Gray Man Project with some shady emphasis on self-reliance (a public records search and a Guidestar dive reveals no record), published his first TikTok on October 11, 2020. He has claimed to be a private investigator. A search with the California Department of Affairs reveals that he is licensed (with a firearms permit) through October 31, 2022. Pesola’s license matches up with an operation called The People’s Detective, which claims to be “a full-service investigative agency with a 30-year track record of successful investigations, high profile cases, and newsworthy discoveries.” (The People’s Detective did not return my requests for comment.)

Pesola’s initial four videos detailed how a Sharpie, a flashlight, and a belt could be used to attack someone and his initial videos shortly after this quartet were carried out with a strain of tough-talking military bravado and alleged expertise. This was apparently enough for Pesola to earn the beginnings of a following, where his relationship to his audience would involve addressing douchebags (while mispronouncing Epictetus, whom he has frequently declared to be his favorite philosopher) and engaging in fairly unimaginative conservative talking points.

As Pesola acquired more of an audience, it took only days for Pesola to go off the deep end with an October 14, 2020 video in which he declared, “Toxic masculinity is a myth…Masculinity is a heightened state of being that all men should strive for.” By October 23, 2020, Pesola began honing the beginnings of his pugnacious TikTok formula, calling some of his audience “motherfuckers” and “miserable pricks.” But this was enough for Pesola to gain 11,000 followers in two weeks. Pesola then started stylizing his voice in a preposterously deep manner to woo more followers. At this point, the strains of misogyny and ugliness that were to become Pesola’s hallmarks still drifted somewhat in the background. But since this was his chief draw, it became more of his raison when publishing videos.

In an October 20, 2020 video, Pesola offered hotel advice, claiming that you didn’t want to get a hotel room on the second floor because there might be “some fucking crackhead breaking in the window and wanting to get in bed with you in the middle of the night. Unless you’re into that.” He called peaceful protesters “fucking retards.” By the end of October 2020, Pesola gradually strayed away from his tips on security and began embracing the beginning of his bullying, going after the “ignorant fucking retards.” He reveled in crude violence when offering “advice” to domestic violence survivors, suggesting that women “turn into the most vicious, fucking, violent psychopath you can imagine in your entire life.” While dispensing questionable wisdom to rape survivors, Pesola giddily declared, “Guys will fuck you with a potato sack and heels on.”

By November 2020, Pesola’s feed had become a reliable hotbed of hideous misogynistic takes. He bemoaned the idea of men facing penalties for hitting a woman while adopting a phony position against domestic violence. (Pesola spent most of his time in this video siding with men who were simply “defending” themselves, concluding in a crude manner, “I don’t care how good the pussy is. Get away from that toxic shit.”) In a November 11, 2020 video viewed by 912,600 people, Pesola reached his first major viral nadir of casual misogyny, claiming that preventing rape was the responsibility of women and that it was a woman’s obligation to parent well: “I got an idea. Be better fucking mothers.” When, on November 28, 2020, a TikTok user named @gishaz called Pesola out on the misogyny of this post, Pesola smugly responded, “So you agree then that the world does need better mothers.”

It took six weeks for Pesola to hit 100,000 followers. And by early December 2020, the fame had swelled to Pesola’s head. He confidently announced, “Hello ladies. I know what makes you tick.” In a multipart series that began on December 6, 2020, Pesola giddily described how he manipulated an escort into almost having sex with him for free, later bragging about lying to this escort by claiming to be an escort, and offering further confabulations that he couldn’t enter into a meaningful relationship because of his false escort role. For Pesola, women are merely sexual vessels to be used — with counterfeit empathy as the tool.

By December 22, 2020, Pesola was referring to himself as a “famous TikTokker” and, with his colossal hubris confirmed by his growing follower base, he declared on Christmas Eve, “Frankly, I don’t give a fuck if I’m likable. Apparently, 160,000 followers is telling me [sic] that I’m doing something right.” And there was more sexism to come: Pesola remarked on the unfairness of men paying child support, offered tips on how to keylog a lover’s phone, claimed that there was no such thing as rape culture (“It’s illogical and just plain fucking stupid.”), reconfirmed his view that toxic masculinity was a myth, and took the side of a man in a marriage split without considering the woman’s perspective (“It sounds like his ex-wife is a righteous cunt.”). By the turn of the year, Pesola had become hopelessly resolute in his hatred of women. When not condemning Nelson Mandela, he claimed that a man giving his phone to his girlfriend was weak (“Oh boy! That’s a red flag towards an unhealthy and toxic relationship.”), demeaned women for not revolving their entire lives around men (“If she doesn’t value your time as her man, then she’s always going to be a waste of time as your woman.”), and condemned women for allowing men to be disrespected.

On November 19, 2020, Pesola risibly claimed that it was important to treat people with different perspectives and worldviews with respect. It was advice that he was not to follow months later when he started using his bully pulpit to crush any position that differed from his own. He started addressing his audience as “fuckfaces” in late January. He engaged in casual fat-shaming with a disturbing eugenics streak, demanded that women make more money as they aged (“Your looks depreciate as you get older.”), claimed that blowjobs were the male equivalent to a woman receiving flowers, claimed that anyone who was offended by behavior was a “stupid fuck,” and falsely claimed that the government was forcing people to get vaccinated.

Pesola did not reply to my questions. But the undeniable strain of misogyny in Pesola’s TikTok feed is clearly the very quality that the TikTok algorithm values the most. This allowed an unremarkable chowderhead in Carlsbad with a toxic strain of sexism to become a small-time TikTok star. Systemic misogyny appears to be permanently baked into the factors that cause TikTok videos to end up on the For You Page. And if you speak out against this nefarious truth, you get banned. In my case, I made hundreds of largely benign videos on TikTok. I offered empathy to people who looked like they were in trouble. I sang songs. I cracked jokes. But none of that matters. Because I dared to speak out against a garden variety thug like Pesola, all that I made is now inaccessible to me. I have no backup copies. Pesola, on the other hand, will be just fine. And it is because Pesola perceives women as little more than shallow little wretches to manipulate. Despite the significant advances of the #metoo movement, hating women is apparently still your hot ticket to social media fame.

5/28/21 UPDATE: Deputy Daniel “Duke” Trujillo is now dead of COVID. This Denver deputy did not have to die. He could have received his vaccination. But as the Twitter user @RacistProgramming reported, Trujillo was heavily influenced by one of Pesola’s anti-vaxx videos.

Denver Sheriff Deputy Duke Trujillo died from COVID-19.

Trujillo posted an anti-vaccine video and pics to his Facebook. https://t.co/okWwzUXSfl pic.twitter.com/LIYfhkcnGG

— Resist Programming 🛰 (@RzstProgramming) May 28, 2021

As of the morning of May 28, 2001, Pesola has also made his TikTok account private:

5/30/21 UPDATE: Faced with intense scrutiny from appalled users, Pesola has deleted all of his social media accounts, including TikTok and Twitter.

Correspondent: Here we have a military strip. But there’s no reference to Iraq. And I wanted to ask you about this kind of balance.

Correspondent: Here we have a military strip. But there’s no reference to Iraq. And I wanted to ask you about this kind of balance.