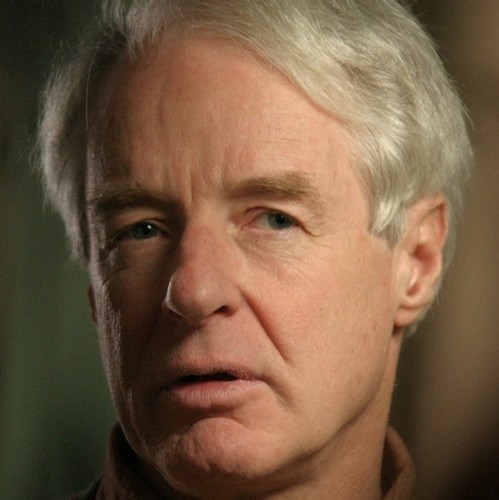

James Gleick recently appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #397. He is most recently the author of The Information.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Giving little bits of your entropy.

Author: James Gleick

Subjects Discussed: Claude Shannon, the origin of the byte, Charles Babbage and relay switches, measuring information beyond the telegraph, bit storage capacity, being right about data measurement, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” information overload, TS Eliot’s The Rock, email warnings in 1982, information compression, George Boole’s symbolic logic, information overload, Ada Lovelace and Babbage, James Waldegrave’s November 13, 1713 letter providing the first minimax solution to the two person game Le Her, game theory, Lovelace’s mathematical aptitude, the difficulties of being too scientifically ambitious, connecting pegs to abstraction, Norbert Wiener and cybernetics, Wiener’s contribution to information theory, Wiener vs. Shannon, mathematical formulas to solve games, Ada Lovelace’s clandestine contributions, Luigi Menabrea, a view of machines beyond number crunching, entropy, the Second Law of Thermodynamics, James Clerk Maxwell’s view of disorder as entropy’s essential quality, dissipated energy within information, Kolmogorov’s algorithms and complexity, links between material information and perceived information, molecular disorder, connections between disorganization and physics in the 19th century, extraneous information, Thomas Kuhn’s paradigm shifts, Richard Dawkins’s defense of dyslexia as a selfish genetic quality, new science replacing the old in information theory, the English language’s redundant characters, codebreaking, Shannon’s scientific measurements of linguistic redundancy, the likelihood of words and letters appearing after previous words and letters, Bertrand Russell’s liar’s paradox and Kurt Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem, Gregory Chaitin and algorithmic information theory, Alan Turing, uniting Pierre-Simon Laplace and Wikipedia, extreme Newtonianism, and the ideal of perfect knowledge.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I wanted to first of all start with the hero of your book, Claude Shannon, who of course is the inventor of the byte. He built on the work of Charles Babbage. Shannon conducted early experiments in relay switches, creating the Differential Analyzer. He made very unusual connections between electricity and light. He observed that when a relay is open, it may cause the next circuit to become open. The same thing holds, of course, when the relays are closed. Years later, Shannon, as you describe, is able to demonstrate that anything that is nonrandom in a message will allow for compression. I’m curious how Shannon persuaded himself to measure information on the telegraph. In 1949, as you produce in the book, there’s this really fantastic paper where he draws a line and he starts estimating bit storage capacity. As you point out later in the book, he’s actually close with the measurement of the Library of Congress. How can he, or anybody, know that he’s right about data measurement when of course it’s all speculative?

Gleick: Wow. That was a very fast and compressed summary of many of the ideas of Claude Shannon leading into Claude Shannon. Well, as you’re saying, he is the central figure of my book. I’m not sure I would use the word “hero.” But he’s certainly my starting point. My book starts, in a way, in the middle of a long story. And that moment is 1948, when Claude Shannon publishes his world-changing paper, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” Which then becomes a book, The Mathematical Theory of Communication. And for the first time, he uses the word “bit” as a unit of measure for this stuff. This somewhat mysterious thing that he’s proposing to speak about scientifically for the first time. He would go around saying to people, “When I talk about information as an engineer and a mathematician, I’m using the word in a scientific way. It’s an old word. And I might not mean what you think I mean.” And that’s true. Cause before scientists took over the word, information was just gossip or news or instructions. Nothing especially interesting. And certainly nothing all-encompassing. I guess the point of my book, to the extent that I have a point, is that information is now all-encompassing. It’s the fuel that powers the world we live in. And that begins, in a way, with Claude Shannon. Although, as I say, that’s the middle of the story.

Correspondent: Got it. Well, as you point out also, information overload or information anxiety — this has been a truism as long as we’ve had information. You bring up both TS Eliot’s The Rock — “Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? / Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” — and, of course, a prescient 1982 Computerworld article warning that email will cause severe information overload problems. To what degree did Shannon’s data measurement account for the possibility of overload? I didn’t quite get that in your book and I was very curious. There is no end to that line on the paper.

Gleick: No. Shannon didn’t really predict the world that we live in now. And it wasn’t just that he was measuring data. It’s that he was creating an entire mathematical framework for solving a whole lot of problems having to do with the transmission of information and the storage of information and the compression of information, as you mentioned. He was, after all, working for the telephone company. He was working for Bell Labs, which had a lot of money at stake in solving problems of efficiently sending information over analog copper telephone wires. But Shannon, in creating his mathematical framework, did it simultaneously for the analog problem and the digital problem. Because he was looking ahead — as you also mentioned in your very compressed run-up. He thought very early about relays and electrical circuits. And a relay is a binary thing. It’s either open or closed. And he realized that open or closed was not just the same as on or off, but yes or no or true or false. You could apply electrical circuits to logic and particularly to the symbolic logic invented by George Boole in the 19th century. So Shannon created his mathematical theory of communication, which was both analog and digital. And where it was digital, it had — we can see now with the advantage of hindsight — perfect suitability to the world of computers that was then in the process of being born.

Correspondent: It’s fascinating to me though that he could see the possibilities of endless relay loops but not consider that perhaps there is a threshold as to the load of information that one can handle. There was nothing that he did? To say, “Well, wait a minute. Maybe there’s a limit to all this.”

Gleick: I’m not sure that was really his department.

Correspondent: Okay.

Gleick: I don’t think you can particularly fault him for that or give him credit one way or the other.

Correspondent: It just didn’t occur to him?

Gleick: No, it’s not that it didn’t occur to him. It’s that — well, I would say, and I do say in the book, that this issue — I’m hesitating to call it “problem” of information overload, of information glut — is not as new a thing as we like to think. Of course, the words are new. Information glut, information overload, information fatigue.

Correspondent: Information anxiety.

Gleick: Information anxiety. That’s right. These are all expressions of our time.

Correspondent: There’s also information sickness as well. That’s a good one.

Gleick: One of the little fun side paths that I took in the book was to look back through history at previous complaints about what we now call information overload. And they go back as far as you’re willing to look. As soon as the printing press started flooding Europe with printed books, there were lots of people who were complaining. This was going to be the end of human knowledge as we knew it. Leibniz was one. Jonathan Swift was another. Alexander Pope. They all complained about — well, in Leibniz’s words, “the horrible mass of books.” He thought it threatened a return to barbarity. Why? Because it was now no longer possible for any person, no matter how well educated, no matter how philosophical, to keep up with all human knowledge. There were just too many books. There were a thousand. Or ten thousand. In the entire world. Well, now, there are ten thousand books printed every hour in the world. Individual titles. So yes, we were worried about information overload. And yes, you can say that Claude Shannon, in solving these problems, greased the skids. But I don’t know whether it’s true or not that he didn’t foresee the issue. It just was an issue that wasn’t in his bailiwick.

Correspondent: Got it.

The Bat Segundo Show #397: James Gleick (Download MP3)