Joe Rogan has significant sway. And with great influence comes great responsibility.

A few days ago, I pulled all of my podcasts from Spotify. In terms of influence, I am about as far from Neil Young and Joni Mitchell (or, for that matter, Roxane Gay) as you can get. But I could not in good conscience allow the art that has taken up happy years of my life to be shared on the same platform as Joe Rogan, who has repeatedly demonstrated his commitment to spreading disinformation and offering a platform for anti-trans rhetoric. Rogan has stood against science (or even commonplace thinking) and, with that stance, debased the courageous front-line workers who have put in long and often traumatic hours to serve the commonweal — often with thankless and even hostile or violent reactions.

But that is my choice. It doesn’t mean I want to silence Rogan. It doesn’t even mean that I won’t listen to him — particularly if some viral clip pings on my radar. It just means that I don’t want to be associated with him. Just as I don’t want to be associated with Nazis (now making a resurgence in Florida), racists, sexists, hatemongers, people who never tip, those who exploit others for their own gain, and numerous other unpleasant individuals who stand against the human condition. This is no different from boycotting Florida orange juice in the 1970s because of Anita Bryant’s hateful homophobia.

Until Sunday, when Rogan responded to the Spotify controversy on Instagram, Rogan had outright flouted his duties as a significant influencer. It was only after Spotify lost $2 billion in market value that Rogan had deigned to say anything.

I am fully committed to free speech, perhaps far more than most people these days. My audio drama, The Gray Area, is devoted to the pursuit of humanism and empathy in narrative form. And Joe Rogan, who isn’t exactly the sharpest blade in the kitchen drawer, is fundamentally opposed to these core tenets. So I stand in solidarity with the 270 members of the medical and scientific community who signed an open letter against Rogan’s unhinged and mercenary fidelity to hate and misinformation. (And, as an aside, Media Matters‘s Alex Paterson truly deserves hazard pay for subjecting himself to 350 hideous hours of that mumbling marblemouth. I wouldn’t subject such an insalubrious assignment on my worst enemy. On the other hand, this did need to be done.)

Joe Rogan has faced controversy ever since he shifted his podcasting empire to Spotify for the kingly sum of $100 million. In September 2020, Spotify employees offered pushback against some of the more unsettling elements of the show — such as offering a platform for transphobic writer Abigail Shrier, in which she suggested that trans people suffered from autism and that social media was little more than a propaganda outlet to persuade young people to transition.

The showdown among Spotify employees and Joe Rogan was framed as a free speech issue. It was presented as wokesters trying to “silence” Rogan. But an examination of the underlying facts reveals that isn’t quite the case at all. Spotify staffers demanded editorial oversight of Rogan’s podcast. And Vice reported that there had been ten meetings between the Spotify employees and various higher-ups. Did these Spotify employees want to silence Rogan? There is no evidence. The Spotify employees simply wanted Rogan to be more mindful and sensitive to the present-day clime. They clearly understood that Rogan was a draw and they did what any loyal employee would do upon seeing a cluelessly intransigent C-level executive who is out of touch with the present clime getting hammered at the holiday party and making inappropriate remarks. They said that they felt “unwelcome and alienated.” They pointed out the dangers of hosting transphobic content. It was not unlike the brave Gimlet employees who stood against former Reply All host PJ Vogt’s toxic behavior. In the case of Gimlet, there were actual consequences. In the case of Spotify, well, as the old saying goes, money talks.

There isn’t a single artist out there who couldn’t use editorial oversight. One’s freedom to express opinions isn’t so much hindered by a careful editorial hand, as it is enhanced by someone who can help a talent find the best way to communicate that view to an audience. And that would include controversial views and opinions that often make people uncomfortable. There have been many times in my life in which I would have benefited from editorial oversight. Like anyone, I’m still learning. Rogan, however, has remained adamantly resistant to anyone helping him to become a better communicator.

Let’s examine the episode that caused a furor within Spotify. If Rogan had offered pushback against Shrier and her fringe shows on his show, then he wouldn’t have attracted concern from Spotify employees, much less trans people who have had to endure significant hate and ridicule for who they are.

But that’s not Rogan did. Here’s a transcript from his conversation with Shrier:

Shrier: A reader wrote to me — I write most often for the Wall Street Journal — and a reader wrote to me and she said, “Listen, I’ve tried to get every mainstream journalist to pick this up. No one will touch it. But my daughter got caught up in this. All of a sudden she went off to college all of a sudden with her friend. She had a lot of mental health issues, anxiety, depression. And all of a sudden, with her group of friends, they all decided they’re trans. And she went on hormones.” And this is happening to parents all across the country. Teenage girls all of a sudden deciding with their friend that they’re trans, wanting surgeries and hormones and getting them. And at first I thought, I don’t need this. And so I tried to get another journalist to take it up. A real investigative reporter. I’m not I’m an — I’m an opinion journalist usually, you know, that’s what I’ve done. And I couldn’t get someone to take it up.

Rogan: Because it’s such a minefield. Because —

Shrier: Yeah because it’s a minefield. Because for some reason, the activists who are do not [sic] representative of transgender adults that I’ve met at all. But the activists had convinced the world that because, you know, they — they, you know, object to anyone’s transition being questioned, we can’t talk about a mental health issue facing teenage girls.

Rogan: Now I’ve heard there’s an issue with some teenage girls who are on the spectrum who wind up getting sort of roped into this idea that that’s what’s wrong with them. Is that one of the things you cover in your book?

Shrier: Yeah, I actually don’t deal with that specifically very much. And the reason is that’s a whole book in of itself. Because a lot of it is true that a lot of girls who are high functioning autistic. And I did interview some experts in autism and that’s when I realized that’s a book of its own, which is that a lot of girls who are high functioning autistic, you know, they tend to fixate and they had they are particularly susceptible to fixating on the idea that they might be a boy when it’s introduced to them. So yeah, I know exactly what you’re talking about in there. They are one part of this phenomenon, but they’re a big part.

This snippet is a complete failing of legitimate debate. Here’s why it’s so harmful and dangerous:

- Shrier uses a single anecdote to paint a broad brush about young girls who choose to transition, framing this as an epidemic. This, of course, is a logical fallacy. It is akin to saying, “Someone told me that they turned into a giant whippoorwill — the size of the Chrysler Building — after eating a chicken mole burrito for lunch. Therefore, having a chicken mole burrito for lunch will transform you into a gargantuan nightjar.” Rogan does not acknowledge this logical fallacy to his listeners..

- At no point does Rogan stop Shrier and say, “Wait a minute. Do you have any tangible evidence for your claim?” Instead, he agrees with Shirer’s fringe view without question, thus endorsing a transphobic view.

- Rogan says nothing when Shrier suggests that transgender activists are incapable of having their assertions questioned. Furthermore, Shrier here isn’t presenting any solid foundation for her claims here. By her own admission, she’s merely an “opinion journalist.” Little more than some hopped up yahoo rambling at a bar.

- Rogan, practicing his usual illiteracy, not only hasn’t read Shrier’s book. But he hasn’t been filled in by one of his staffers on the content that is contained within it. He’s “heard” there’s an issue with teenage girls on the spectrum, but has no actual evidence to back this up. More transphobia.

- Shrier suggests, quite preposterously, that a large proportion of teenage girls who are exploring their gender identity are autistic. Again, Rogan does not question this transphobic belittling of teenage girls. He does not interrogate this unfounded assertion. Thus, an impressionable Joe Rogan listener comes away from this colloquy believing that what Shrier has said is true.

Joe Rogan takes this approach because he understands on some rudimentary level that allowing pernicious views like this to be propagated without question will (a) upset and infuriate a lot of people and (b) win him attention and social media buzz.

Now I’d like to believe that Joe Rogan can change and use his platform for good. One of the baleful realities about anyone getting cancelled is that our culture is fundamentally opposed to the basic human truth that people can learn and change. Furthermore, objecting to Joe Rogan for promulgating these views doesn’t mean that he’s cancelled. It means that you insist on stronger editorial oversight. It involves acknowledging that the “views” that Rogan peddles on his podcast represent 2022’s answer to endorsing segregation without leaving any room for the audience to think for itself.

Additionally, Rogan simply cannot be cancelled. Even if Rogan were to be exiled from Spotify, it’s abundantly clear that he would still have a large platform. He has an estimated reach of 11 million listeners per episode. He has a rabid fan base that hangs on to his every word.

Thus, it is a reasonable position for any thinking person to object to the company that is enabling Rogan. It simply isn’t a free speech issue. It’s the marketplace of ideas deciding what constitutes food for thought.

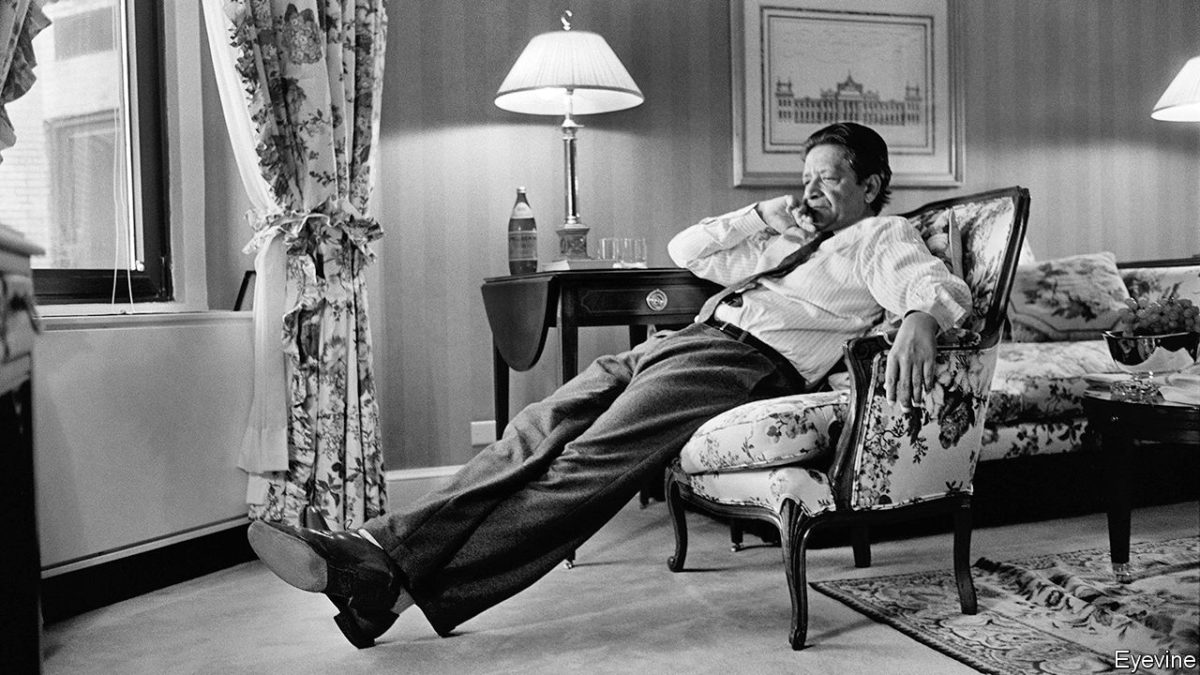

I’ve delivered variations of these sentiments over the phone to amused literary friends, who, when they weren’t laughing their asses off over my five minute anti-Naipaul soliloquies, were good enough to urge me to forgo the semi-scholarly format of this ridiculous years-long project and simply speak from the heart. I shall do my best to be as thoughtful as I can about my Naipaul bellicosity, which is, alas, the only way to move forward with this project. I can tell you this much. Not even

I’ve delivered variations of these sentiments over the phone to amused literary friends, who, when they weren’t laughing their asses off over my five minute anti-Naipaul soliloquies, were good enough to urge me to forgo the semi-scholarly format of this ridiculous years-long project and simply speak from the heart. I shall do my best to be as thoughtful as I can about my Naipaul bellicosity, which is, alas, the only way to move forward with this project. I can tell you this much. Not even