When Elizabeth Hardwick wrote of the “sweet, bland commendations” that plagued the book reviewing scene in 1959, she was protesting a few anti-intellectual developments at the time: (1) the hubris of then New York Times Book Review editor Francis Brown claiming in an interview that his outlet was superior to the Times Literary Supplement simply because “[t]hey have a narrow audience and we have a narrow one” (while failing to comprehend the editorial rigor then in place at many English newspapers) and (2) the fact that 44.3% of the reviews appearing in Book Review Digest were non-committal, thus providing a laughably self-undermining idea of what the book review was (one sees such a disastrous approach in place presently with The Barnes & Noble Review, which, in deference to its corporate entity, publishes mostly raves, regularly stubs out passionate voices, and fires any freelancer who offers fair journalistic reports on the parent company in another venue). In other words, Hardwick was pointing out that book reviews were little more than publicity, with “Time readers, having learned Time‘s opinion of a book, feel[ing] that they have somehow already read the book, or if not quite that, if not read, at least taken it in, experienced it as a ‘fact of our time.'”

Hardwick was not suggesting that the book review was dead, nor did she entirely stand against critical writing. She was calling for robust standards standing independent from the sausage factory. And when one looks at a woefully deficient “outlet” like Jacket Copy — with its superficial concerns (just in the last few days) for Keanu Reeves poetry books, its interest in Slavoj Žižek only in relationship to Lady Gaga, and Stieg Larsson considered only through personal gossip — one observes very clearly how the literary journalism’s clear debasement has been dyed to the roots, with any natural voice destroyed in the noise of forcing commenters to sign on to Facebook.

Despite all this, I must stand firmly against Elizabeth Gumport’s recent suggestion that we nuke the site from orbit. Unlike the previous Elizabeth, whom Gumport quotes, this Elizabeth doesn’t stand for any corresponding set of virtues. She asks for an end to the inanity of a book review outlet being “nothing more than a list of books,” but she assumes that “[n]ot only do we not want to read about Gary Shteyngart’s latest novel, we don’t even want to know it exists.” To which this reader of Larsson, Shteyngart, Joyce, Mieville, and Go the Fuck to Sleep responds, “Speak for yourself, O Boring and Incurious One!”

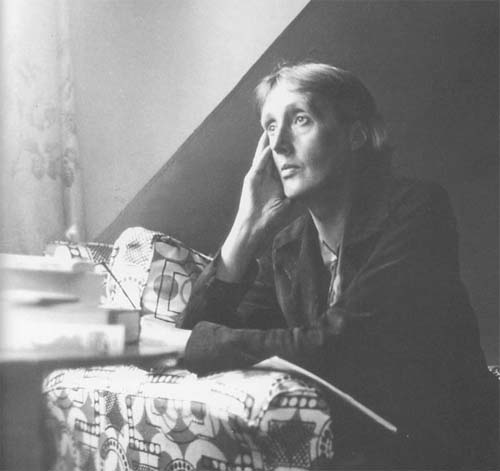

In quoting Virginia Woolf’s 1939 essay, “Reviewing,” Gumport fails to understand that Woolf was condemning a scenario whereby sixty reviewers at once assured the reader that some book was a masterpiece, while pointing out that the reviewer’s position more than seventy years ago was unsatisfactory (then as it is now). Reviewers were then forced to write quick spurts in haste for scant pay. And it is this observation (rather than the asterisks) that begs the comparison to Kirkus and Publishers Weekly — outlets that have both been slashing their compensation in recent years, even charging publishers for the privilege of being reviewed. (Seven years after Woolf, George Orwell offered his memorable portrait of a book reviewer as “a man in a moth-eaten dressing gown sit[ting] at a rickety table, trying to find room for his typewriter among the piles of dusty papers that surround it.”) It does not occur to Gumport that improving the reviewer’s dim station — whether by offering her more adequate compensation or hiring one more committed to well-grounded thought and passion writing at less frequency — may actually improve the quality of reviews. Gumport also doesn’t seem to understand that Woolf was clearly having a laugh with her piece:

There remains finally the most important, but the most difficult of all these questions — what effect would the abolition of the reviewer have upon literature? Some reasons for thinking that the smashing of the shop window would make for the better health of that remote goddess have already been implied. The writer would withdraw into the darkness of the workshop; he would no longer carry on his difficult and delicate task like a trouser mender in Oxford Street, with a horde of reviewers pressing their noses to the glass and commenting to a curious crowd upon each stitch.

With Woolf’s wry context revealed, Gumport reveals herself to be an upholder of the n+1 aesthetic: humorless misreads of seminal essays sprinkled with polemical cayenne. In failing to think, Gumport is no different from her characterization of book reviews: pointless in her condemnations, snotty and recidivist in suggesting that nobody is interested in a review aside from the author (especially when so many authors wisely ignore the takedowns and the hatchet jobs of their work), and, most criminally, without so much as a positive counterpart. As my online colleague Michael Orthofer has suggested, “the whole exercise appears pointless — like a piece ‘Against Blue’ or ‘Against Soup’.” Or, for that matter, an essay called “Against Essays About Reviews That Have No Corresponding Set of Virtues.”

UPDATE: Tom Lutz has also responded at the Los Angeles Review of Books.