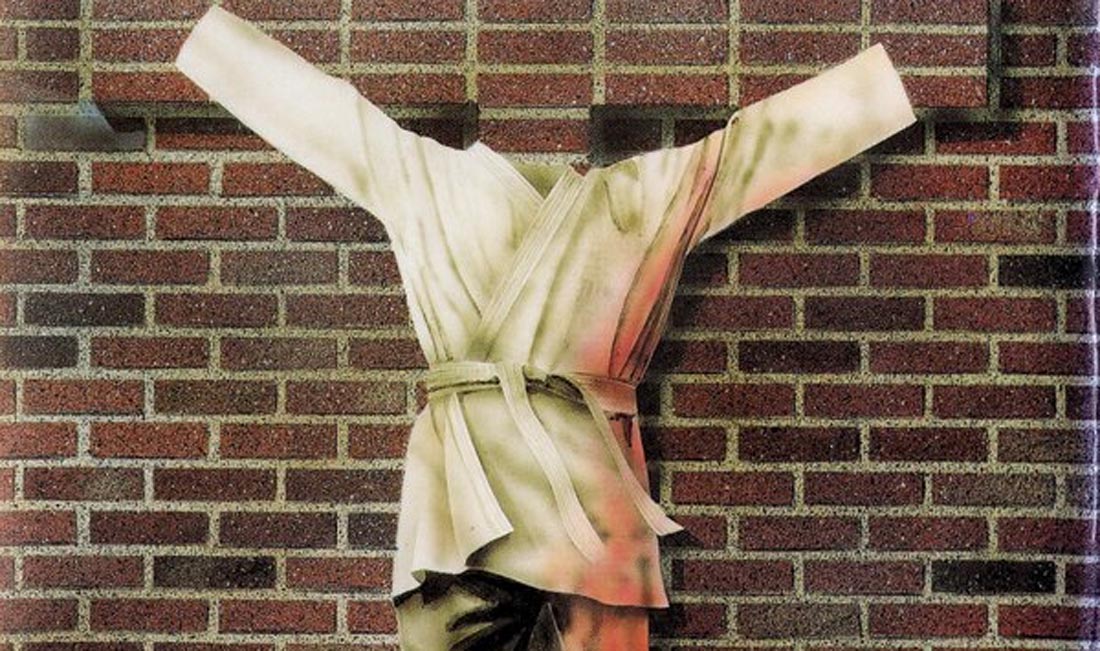

This one hour radio special is the first in a series of “at-large” conversations presently categorized under the old “Bat Segundo” label. It features a rare interview with Jack Butler, author of Jujitsu for Christ, a highly underrated novel that has recently been reissued by the University Press of Mississippi.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Author: Jack Butler

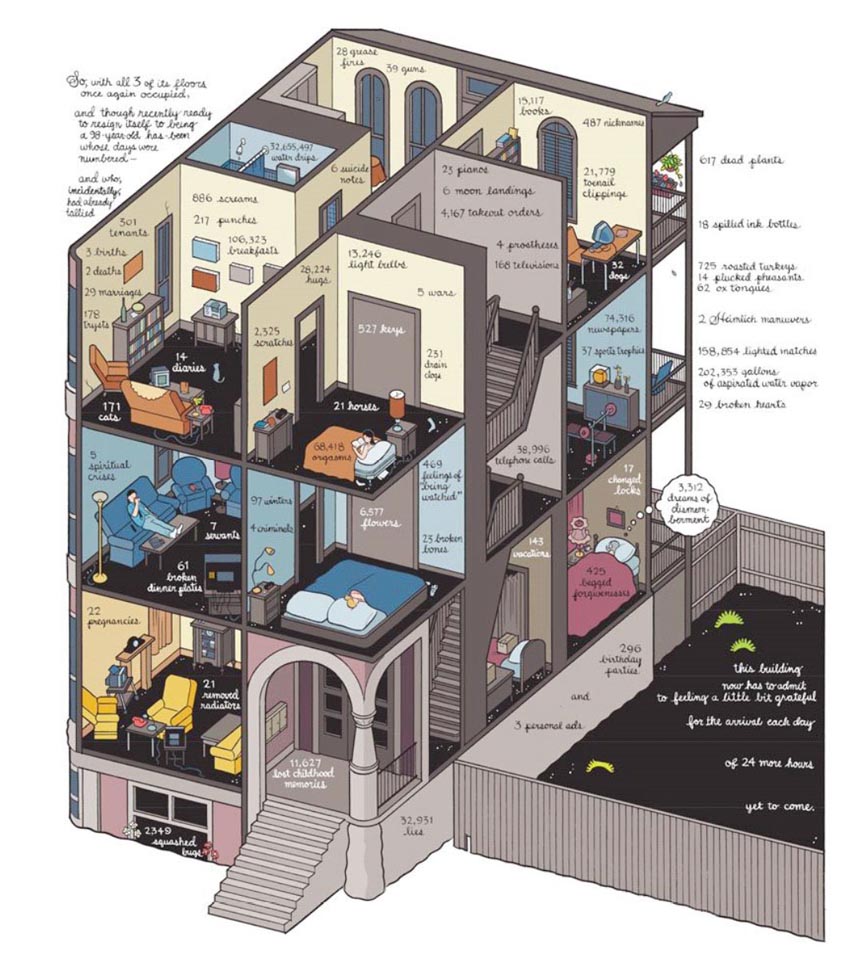

Subjects Discussed: Moving west over a lifetime, having a double bachelor’s in English and math, the yin-yang existence, reading science fiction as a boy, why the stars are so inspirational in the Delta, using the Holy Ghost as a narrative device, Lautréamont, narratives within the Bible, Ulysses and The Waste Land, theological implications within fables, Finnegans Wake, speaking in tongues, starting a book with only 60 pages, becoming an accidental novelist, the poet’s life, the strange yet highly modest financial incentives of novels, the Judo for Christ Club, Tom LeClair and “prodigious fiction”, comparing novels with a 7-Layer Burritos, how to present information within a story, the College of Santa Fe, Los Angeles as a source of escape, why Butler’s fiction left the South, writers who become unintentional spokesmen for the South, not being bound by assumptions, “authentic” vs. “smart,” Eudora Welty, Faulkner, science fiction and Southern literature as lowbrow inspirational territory, literary authors who scavenge from genre and write unsuccessful novels, how genre can be used to write meaningfully about humanity, African-American stereotypes, caricatures, missed opportunities because of bigotry, living in shanties, common experience, scavenging from comics and used books to form a borrowed bedrock of knowledge, the character “Jack Butler” in Living in Little Rock with Miss Little Rock, “autobiographical fiction,” the neediness of novelists, combating desperation in a world that increasingly devalues risk-taking authors who don’t sell, Bum Festrich modeled on the Clarion-Ledger‘s Tom Etheridge, using racist newspaper rhetoric as an unsettling guide for fictional perspective, writing about sex, religious blasphemy vs. sexual blasphemy, Hugh Hefner’s philosophy vs. the Baptists, being part of the way actuality goes, why religion in fiction often causes the author to create a comparative ideological construct to present contrast, gay rights, the Belgian Malinois making mysterious noises in the back, corporeal collision in debut novels, approaching the holy through the material, chalk talks, tragicomic side characters, when the ABA voted Jujitsu worst title, mixing the funny with the repulsive, writing about humidity in Mississippi, massive IBM clone computers in the 1980s, writing a book on a 400 pound computer, slowing down writing speed, whether or not a writer needs a sense of compulsion, chasing down a locale in one great shot, allowing the reader to experience life as Butler saw it, The Illumination of Elijah Lee Roswell, what happened with Butler’s agent, the dangers of writing with the idea of money in mind, the virtues of academics, forbidden styles, the benefits of rebellion, people who sell out, clearing the head of extraneous voices,

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I wanted to first of all talk about how you got your start. You were a poet before you were a fiction writer. And I also know that you have a bachelor’s in English and a bachelor’s in math. And I was wondering. How does a guy like you have the yin-yang thing going on here? It seems that you have a yin-yang thing in terms of what you studied and what you ended up doing as a writer.

Butler: Yeah. A lot of that — at least as far as math and the arts go — is that I loved science fiction as a kid. I used to read it all the time. Most of it is literarily horrible. But I was in a Baptist conservatory in Mississippi and they weren’t really aware of science fiction. So that was something I could get away with and what I really loved was just the ability to speculate. You know, that the world might be different from what was right around you. For pretty obvious reasons. But I’ve always been interested in mathematics. I think one of the sad things about our culture is that we have such a dichotomy set up between art and science or math. I mean, the two things I say that people are most afraid of are poetry and mathematics.

Correspondent: Yeah. How has math and poetry encouraged you to speculate? Both in terms of your imagination and in terms of, for example, books like Nightshade?

Butler: I guess it’s just that they give me the tools. I’m pretty picky about details, even though I do get some things wrong. Just in case there’s anybody listening, I’m not a medical person at all and I gave the exact opposite cure for angina. I said digitalis. And that will kill you. (laughs)

Correspondent: (laughs)

Butler: Aside from that, I had to not only get the gravity of Mars right. I had to allow for it in every action. Which you just don’t really see very much. So it’s more nearly that it’s given me the tools to do what I’m psychologically inclined to do.

Correspondent: So with science fiction, do you feel that it’s that speculative nature that really makes it fiction or meaningful? That this was the drive for you when you were growing up reading a lot of it as a boy, as a young man. That kind of thing?

Butler: Yeah, right. And as I said in the interview with Brannon (PDF), I believe, the Delta had a big wide sky. Because of all the flatland and not too many trees. So in spite of the humidity, you could really see the stars. And I loved the stars. That got me going on that.

Correspondent: Your first three novels (Jujitsu for Christ, Nightshade, and Living in Little Rock with Miss Little Rock) all feature some intriguing narrative mode somewhere between direct first person and a quite literally godlike omniscient voice. It almost reminds me, to some degree, of Lautréamont’s narrator in the way that you suggest to the reader that the narrator has lived and this allows the narrator to share some experience with the reader. And I’m wondering. Why did you need this particular type of halfway narrator to tell a story for these first three books?

Butler: Well, I’ll go back to — it’s not really an anecdote, but when I first thought of having the Holy Ghost — and I hasten to add that I mean this as a model of the Holy Ghost. I’m not pretending to represent the actual thing, if it even exists. But it’s like what Wallace Stevens said. “Not as a god, but as a god might be.” Well, not as the Holy Ghost, but as the Holy Ghost might be. And I couldn’t believe that nobody had ever picked up on it. You had the ability to have both first-person narration and a justified reason to switch personas. It was wonderful. And, of course, I got all that Holy Ghost stuff, a lot of it, growing up. It was drilled into me. So it was a chance to play with that a little bit. The Holy Ghost is narrator in Living in Little Rock with Miss Little Rock, but one of the main problems with Westernized Christianity is that we don’t have a trickster god. And of the candidates, I felt the Holy Ghost was the best candidate for that. So the Holy Ghost is kind of a trickster there. As for the other, one of the things I really like to think about is the nature of individuals. The nature of the individual. Mind. And so playing on narrators lets me play on that.

Correspondent: I’m wondering if this reflects any kind of storytelling you heard growing up. That when people told you stories, either around the house or around the town, that people were telling you the absolute truth or perhaps inserting their own asides. Was it something like that?

Butler: Well, it’s true that people love anecdotes in the South. I think I’ve really gotten more of my tendencies from the fact that my father stood up in the pulpit every week and talked. So that’s always seemed to me to be a natural thing to do. And like you point out, there were a lot of things that didn’t scan for me with the stories I was told. And the Bible, it’s stories. I love the Bible. But I view it as a library, not as a book. It was written over several hundred years, maybe a thousand or more, by different people with different conceptions. And it’s more fascinating as a narrative than anything else. So my storytelling probably had more to do with that. But there’s a background nature that Southerners in general love language and they love to tell stories and there’s a premium put on wit. So I think that was so naturalized without thinking of it.

Correspondent: So if the Bible is a library, what is the Ulysses or The Waste Land of the Bible?

Butler: Well, it’s more beautiful than The Waste Land. Ecclesiastes is one of the more beautiful things ever written in my opinion and it’s very much — not quite nihilistic, but Ecclesiastes very plainly does not countenance belief in an afterlife. It says people are just like grass. Like the grass of the fields. We come from the same kind of place and we go to the same kind of place when we die. Nobody imagines a heaven for grass. So if we’re the same as grass, that has a lot of theological implications.

The Bat Segundo Show Special (“#499”): Jack Butler (Download MP3)