Gary Shteyngart appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #352. Mr. Shteyngart is most recently the author of Super Sad True Love Story. He previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #121 and was ambushed by a Noah Weinberg type earlier in the year.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Too old and too much of a hack for Conde Nast’s cryogenic chambers.

Author: Gary Shteyngart

Subjects Discussed: [List forthcoming]

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: You’ve probably seen this video of this 11-year-old who’s being cyberbullied by 4chan. Did you hear about this? She’s going by the name of Slaughter. And there’s a video where her dad is shouting in the background. And it’s truly horrifying. Surely, I think people would still value their privacy to some degree. Or they would say, “This is going way over the line.” Harassing people. Providing every bit of personal information. I mean, that’s got to trump any seduction by technology.

Shtyengart: Who knows? Things happen so quickly. Our values are changing so quickly. I mean, one of the things that this book doesn’t state, but maybe believes, is that change is okay. Change is going to happen. The end of slavery was good. Racism, anti-Semitism, homophobia — the dilution of all these things in states outside of Arizona. That’s good. But change happens quicker than we’re able to accommodate it. Because we are really flesh and bone and certain whatevers going on in our heads. But there’s only so much we can do. And when we’re addicted to constant change that’s changing at a breakneck speed, what happens when the change overruns us and begins to condition this group mind that we have brought together? It begins to condition us more than we condition the group mind. That can be very depressing. I mean, going back to the television people — when television was revealed — there was a similar worry. But what this does is a little more insidious. It takes away our privacy, for one thing. But it also deputizes all of us to be writers, filmmakers, musicians. Which sounds lovely and democratic. But when a book ceases to become a book, when a book becomes a Kindle application, when it become a file — how different is it in the mind of somebody from any other file that you get? Sitting there at your workstation — if you’re a white-collar worker — all you do all day long is receive bits and bits of information. And in some ways, you begin to privilege these bits of information. But in another way, one email is as good as another. It’s all just coming at you. Streaming at you. You go home. What’s the last thing you want to do? The last thing you want to do is pick up a hard brick like the one I’m holding right now, open it, and begin to read linear text for 330 pages. It’s the last thing you want to do. Who the hell would want to do it? And I think that because America is such a market economy, there’s still a real love of storytelling. That’s why you look at something like The Wire, The Sopranos, Mad Men. You know, what they’ve done is they’ve very cleverly — and they’ve talked about this — they’ve repurposed fiction — the way it used to exist between covers — in a way that can be transmitted inside an eyeball, in a way that satisfies our craving for storytelling. But without all the added benefits that you get from a book.

Correspondent: Hmmm. Well, I don’t know about that. I mean, to some degree, by having jokes and by writing an entertaining book — which I think this is an entertaining book…

Shteyngart: Thank you.

Correspondent: …you are kind of contributing towards this entertainment-oriented storytelling.

Shteyngart: That’s right.

Correspondent: What makes you different, eh?

Shteyngart: Well, you hit the nail on the head with your big hammer. I still believe that fiction is a form of entertainment. In my crazy world, which may not exist, I’m still hearing about a book that I have to read. And I’m getting out of bed. And I’m running to the bookstore. And I’m buying it. In the way that people run to the cineplex. I’m excited. And that’s what I want fiction to do. If it doesn’t entertain me, then it’s work. When I was researching parts of this book, I had to read a lot of books that were not entertaining. And they were work. What worries me is the academization of literature. When it becomes just an academic pursuit, where we sit around, we create serious works that are then discussed by serious people in serious settings, and the entertainment value is nil. And we become a small tiny society that’s obsessed with things. In other words, we become where poetry is today. Utterly irrelevant. Beyond a certain beautiful wonderful circle of people. And the poetry hasn’t gotten any worse. The poetry’s great. And the fiction hasn’t gotten any worse. Some of it is amazing. But the way we approach these things has become too serious.

Correspondent: Well, to what degree should books be work? I mean, I’d hate to live in a world in which Ulysses was banned simply because it was considered to be too much work. I find it a very marvelous journey to just sift into all those crazy phrases and all that language. But it doesn’t feel like work to me. And I don’t think it feels like work to everybody. And we still have Bloomsday and all that.

Shteyngart: I’m not talking about Ulysses. I’m talking about self-important crap.

Correspondent: Like what?

Shteyngart: Well, I’m not going to say.

Correspondent: Ha ha! Very convenient.

Shteyngart: Very convenient. I’m not going to say. Madame Bovary. Talk about a page-turner. I can’t put that thing down. I read it all the time. Jesus Christ, and there’s still part of me that thinks, “Don’t do it. Don’t do it, Madame B. Stay away from that schmuck.” Because it’s so damn involving. It’s brilliant. It’s funny as hell. You know, the apothecary. There’s so many elements in it that are working. It’s perfectly researched. The language is just right. It doesn’t — I suppose it could be considered work. But it’s not any more work than one needs to do in order to gain the maximum enjoyment and understanding of these characters.

Correspondent: Yeah. But isn’t there some sort of compromise? Aren’t you trading something away for this happy medium? Are we talking essentially to some degree about approaching books and literature as if it’s a middlebrow medium?

Shteyngart: Oh what does it mean? Middlebrow, lowbrow, highbrow. These brows. I raise my brow at those brows.

Correspondent: Very bromidic

Shteyngart: The whole bromidic stuff is nonsense. What makes Jeffrey Eugenides or Franzen’s works — what makes them stay in our minds? They use whatever language they want. If they need to deploy highfalutin language, they’ll do it. If they need to use street slang, they’ll do that. The range is always there. And you try to capture a world. A place and time you try and capture as best as you can with the best people who you can deploy. The best characters you can deploy doing them. And to do that, you need to care about these people. Maybe I failed. But I certainly have tried with Lenny and Eunice more so than with anyone else. I’ve tried to live inside their skin. I’ve tried to make myself feel the love that they both have toward each other in this very difficult world. And you know, that doesn’t sound highbrow. But to me, it’s the most important thing I can do with my art.

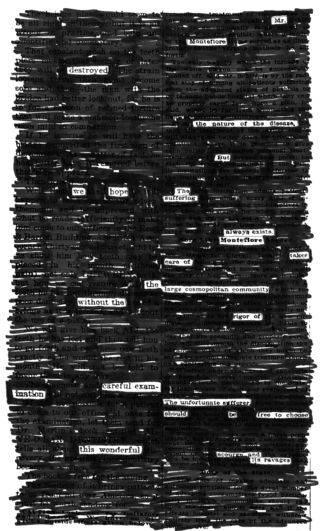

(Image: Morbinear)

The Bat Segundo Show #352: Gary Shteyngart II (Download MP3)

I don’t think the lackluster business had much to do with Michael Cera. But it’s worth observing that Cera has yet to prop up a phenomenally successful Hollywood movie on his presence alone. He’s found commercial success as a supporting character, although Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist, a $10 million movie that grossed $33.5 million, might qualify as a modest success. But when one considers that Scott Pilgrim‘s budget was closer to $100 million, the decision to use Superbad/Juno momentum as a selling point wasn’t terribly wise. Cera, assuming audiences haven’t tired of him by now, will probably be just fine if he can figure out a way to reinvent his one-note Williamsburg hipster schtick and keep his acting roles confined to second bananas. The man lacks leading man gravitas, and now has the commercial track record to prove it.

I don’t think the lackluster business had much to do with Michael Cera. But it’s worth observing that Cera has yet to prop up a phenomenally successful Hollywood movie on his presence alone. He’s found commercial success as a supporting character, although Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist, a $10 million movie that grossed $33.5 million, might qualify as a modest success. But when one considers that Scott Pilgrim‘s budget was closer to $100 million, the decision to use Superbad/Juno momentum as a selling point wasn’t terribly wise. Cera, assuming audiences haven’t tired of him by now, will probably be just fine if he can figure out a way to reinvent his one-note Williamsburg hipster schtick and keep his acting roles confined to second bananas. The man lacks leading man gravitas, and now has the commercial track record to prove it.