It was five years ago when I got the news. Weeks after I lost my mind and I became unhinged and I hurt people with words that I remain deeply ashamed of and I attempted to throw myself off the Manhattan Bridge to end my life and I issued numerous heartfelt apologies and I was spending my subsequent time trying to dig my way out of sadness by extending empathy to people who were more damaged than me in a Bellevue psych ward.

Then it happened.

That’s when the psychiatrist took me into a room and gently said the words that startled me: “Ed, you have bipolar disorder.”

I’ve never confessed this to anyone outside of a few of my closest friends. But I’m saying it now. Publicly. Because I want to own who I am.

I have a disability. And I no longer want to feel any shame about my condition.

I know that I can still live a healthy and positive life. I know that I’m usually a great pleasure to be around and that plenty of people who have taken the time to know me are incredibly understanding and see the great good in me. I held down a job for four years before resigning to pursue other opportunities. I put together an audio drama out of my apartment from nothing, one featuring dozens of tremendously talented actors who are all dear to my heart. I went from being homeless and broke to having my own place in Brooklyn within nine months — a far from easy trajectory. I have devoted every day of the last five years to performing a secret good deed to pay back the universe for any hurt that I have caused people. I know that I have changed — and even saved — numerous lives for the better, but I still believe it’s incredibly self-serving to discuss all the good that I have done. So I usually stay silent about all this.

I have learned that I have to let people make the choice to have me in their lives and to see me for who I truly am. You can’t stack the deck when it comes to social bonds. This has made me, on the whole, a lot happier.

Still, I am very sad and hopeless when the holidays come around. Because this is the time of year that represents an anniversary that often stops me in my tracks and leaves me paralyzed in bed for hours, unable to read or write or watch movies or edit audio or even respond in a timely manner to the texts of friends. And the shame is so deep that, as of right now, I somehow cannot even find it within me to accept a friend’s incredibly generous invite to join her family for Christmas dinner. Because the idea of not having a family, and the crazed associative seduction that comes from believing a narrative in which nobody loves or cares for me, is all part of the black dog’s insidious plan to take over my life.

I know that I have to be on heightened alert before December 26th. When that glorious day comes around, I am usually the happiest. Because I am finally at peace. Until the next year rolls around. You see, the black dog likes to come out and bark during the holidays — as it did recently when a man told me that he would beat me to an inch of my life on the subway because he thought that I was looking at him when I wasn’t. And I was so hopped up, so fully prepared to get into a fistfight with the bastard and show him who was boss. Thankfully a kind soul interceded and there was no violence. The black dog kept growling. He was thrilled by the promise of shaking himself loose from the leash and the cage. I challenged a film critic a little too hard on Twitter over the most trifling subject imaginable and I allowed a writer who I had once admired to debase and belittle and disrespect me and I responded to him — stupidly and privately — with four emails (three vituperative, the last an apology for the previous trio but a firm effort to stick up for myself) expressing how much he had hurt me for cavalierly writing me off and dismissing me after all that I had done for him over the years and all that he did not know about me or my life. It was disgraceful. I want to be clear that I’m not proud of any of this. I was so beaten down from all this that I posted a series of gloomy tweets (since deleted), including a poll asking users if the universe was better off without me. Friends became concerned. God damn that black dog. What a selfish asshole. Causing people worry. Upsetting people dear to me. Wanting to strike lexical terror against people who didn’t deserve it. But I’m grateful to my friends beyond words. I am also deeply ashamed of how I fell victim to the black dog. I received texts. Direct messages. Phone calls. One of America’s most trusted newsmen even tracked down my number and called me to make sure that I was okay, gently telling me that I was irreplaceable and listening to me gab for a ridiculously long time, understanding all the while that this was my way of finding humor in a terrible predicament. It was one of the sweetest things anybody could do. I would defend that man with my life.

What all these incredible people were trying to tell me is something I never got to hear five years ago: “Ed, you have bipolar disorder, but it doesn’t mean that you can’t live a life and it doesn’t mean that we don’t see how you’ve turned your life around and it doesn’t mean that we don’t see the love you give out into the universe. You, in turn, are loved by us.”

That’s it. That’s all I needed to hear. It’s simple really. Love. It chases the black dog out of the room. It’s kryptonite against bad feelings. You’d think that people would recognize that love is the very quality that people would cleave to when others are feeling troubled. But in an age of cancel culture, in an epoch in which making sweeping judgments about who a person is based on a few social media snapshots is now the norm, we’re living in a world in which love is either disposable or at a premium.

This is one of the reasons why it’s taken me five years to own up and be up front about my disability. When people you love betray you and belittle you when you’re down and out, it represents a crippling pain that takes many years to reckon with. When people intuitively detect a moment to attack you as you’re doing your damnedest to be your best and truest self — and there’s no room or space for even the smallest screw-up — that’s when the shame sweeps over you. That’s when the charlatan humanists come out of the woodwork and say, “Hey, be a better person, you son of a bitch!” And the level of rage you feel because some mean-spirited and unthinking dope has summarily dismissed all that you’ve done to be better invites the black dog to dart out of the sagebrush with impunity. I don’t know if anybody can understand or sympathize with that. Looking at how my anger was expressed from a more objective perspective, I’m hard-pressed to empathize with the guy who was motivated by the black dog. But empathize I must. Because to not do so is to give into shame that deracinates personal growth.

The shame was planted not long after I was released from Bellevue. By a vicious podcaster who feigned friendship and who kept badgering me for an interview by phone and text and who I begged to leave me alone. I was trying to recover while living in less than ideal conditions: a crowded room in a homeless shelter in which violence was a regular occurrence and one had to be very careful. I finally agreed to talk with him so that his phone calls and his messages would stop. The podcaster kept saying, “People will understand you after this. Trust me.” Did he not know that I was still trying to comprehend myself? The podcaster proceeded to paint me as the greatest scoundrel who ever lived: a villain unwilling of forgiveness or understanding who had planned this strategy for attention-seeking all along. With casual cruelty, the podcaster negated the terrible truth that I was trying to grapple with: that I was deeply unwell and that I needed to adjust the way in which I lived so that I could be a functioning member of society. The look of selfish relish and rampant opportunism on his face. The way he sipped greedily from one cup of coffee and didn’t even offer to buy me one when I had a grand total of thirty-seven cents to my name. The methodical way that he gleefully punched down as I traced the spot on the bridge where I had tried to off myself. It was all shocking conduct. Behavior that I would never, not even in my darkest hour, offer to my worst enemy. And I was powerless. Desperate. Living with pain. All because I wanted to oblige and be understood after a significant share of people had permanently and justifiably departed from my life.

The shame was furthered by my toxic family. They refused to help me, not even offering me a place where I could simply sit for a few weeks and reckon with the pain of losing everything. They actively and enthusiastically left me for dead. I was forced to sever ties for my own emotional and mental health. The shame got hammered further by my ex-partner, who I had pledged in good faith and as I was feeling debilitating despair to leave alone and not bother again. She used the bipolar diagnosis as a weapon, an occasion to seek needless revenge. She sent me a legal letter in which the attorney declared that I was “retarded,” among other misleading legalese that dehumanized me and reduced me to a sobbing ball of nothingness before I could even come to terms with the truth of my revealed life. But I understand why she did this. I hurt her terribly with my crack-up and bear her no ill will. I was forced to show up in court with a court-appointed attorney on the morning after I had been abruptly moved without warning at two in the morning to another homeless shelter in East New York. I was penniless. I begged the staff to borrow a MetroCard and a razor. I somehow managed to arrive at the court fifteen minutes late dressed in the only sportscoat and tie that I had. That dreadful morning, my identity was attacked with relish. Friends were shocked by her behavior. They were shocked by my family. But I still had love from this small but growing cluster who realized the true score.

It’s bad enough being publicly shamed for words and actions that you never actually committed — such as the time last year in which the audio drama “community” bullied me days before Christmas and invented a series of vicious lies and uncorroborated falsehoods about me — ranging from me being a pedophile to living alone with chickens to harassing people who I had sent nothing but benign messages to — after my audio drama, The Gray Area, won a coveted Parsec Award. The holidays are bad enough for me, what with a family that has disowned me and the way in which so many people who need our love are left in the dust due to the selective application of what constitutes “holiday cheer.” But last year’s attacks sent me into a tail spin of heavy drinking and suicidal ideation in which I didn’t know if I was going to make audio drama again. Thank heavens I had the generous support of friends who patiently stayed on the phone with me and selflessly gave their time when they were very busy. Thank heavens I had an incredibly talented and kind cast who saw that I treated them well and who knew I kept things fun and relaxed and who still wanted to work with me. Months later, I was writing and recording again.

If you’re bipolar, you do have to reckon with and be honest about the behavior that you have actually committed. That’s already a hell of a handful. You look back at the past and you don’t recognize yourself. But if you’re bipolar and you’re something of a public figure, then you also have to deal with a set of false narratives on top of the unruly true one that you’re already trying to nail down.

I want to be clear that I’m not asking for your empathy or your pity. Whether you think I deserve it or not is not my business. And it shouldn’t be. Nor do I want to suggest that I’m using my bipolar disorder as a “Get Out of Jail Free” card. I’m simply telling you how it is. If you think I enjoy occasionally lashing out when the black dog is tearing into my leg with his vicious teeth, believe me I don’t. I don’t enjoy it anymore than the depressed person enjoys feeling sad but who is told by others who do not understand mental illness, “Say, why don’t you cheer up?” As if we people afflicted by black dogs haven’t considered these obvious solutions. If it were possible to instantly wake up one day and be permanently rid of the black dog, I’d do it in a heartbeat. The good news is that I’ve made adjustments and this isn’t occurring nearly as often as it used to. Thanks to therapy, I am quicker on the draw when it comes to shutting the black dog down or instantly apologizing on the rare occasions when he does growl and he makes people very afraid. I am tremendously blessed to have people in my life who are understanding of this. Perhaps one day, if I’m lucky, the black dog will permanently disappear. But one never knows with bipolar. It can either last a few years or stay with you over the course of a lifetime. There is no cure for this. But great men, such as Lincoln and as documented in Joshua Wolf Shrenk’s excellent book Lincoln’s Melancholy, did find strength from their despair.

For now, I know the black dog is there. And December seems to be the time when he takes his destructive constitutional.

What I would like to ask of you — as we approach a new year and a new decade and I’ll make the promise as well — is to consider the very real possibility that the person you’re gleefully maligning isn’t the big bad wolf you’ve made him out to be. That he may be actively working on his problems. That he may even be reachable. That responding with hatred may very well perpetuate a vicious cycle that might prevent the person from growing or excelling and that the tragedy of this stifled possibility greatly outweighs your umbrage. That the person is probably more likely to understand his bad conduct if you give him the time and the space. If you show him love.

You can stop an apparent bad apple instantly in his tracks with kindness or a joke. I’ve done it myself many times. Months ago — and this is a story I’ve never told anyone, not even my friends, until now — a man pulled a knife on the 2 line and threatened to cut himself and others. And maybe this was stupid and reckless of me, but I felt overwhelming empathy for him. I started talking with him. And I asked him who he was and what his life was like. And I kept at it. I had somehow entered a zone. A zone of feeling something bigger than myself. A zone of needing to help this man find peace. Because while I have never threatened anyone with a knife, I saw the pain in his eyes and heard the tremble in his voice. And I told the other passengers that I had this, even though I was flying by the seat of my pants and I wasn’t sure how it would turn out. But I kept at it. And I got him to laugh at my jokes.

That’s all the man needed. Love. Laughter. A sense that he belonged.

And do you know what he did? He put down his knife on a spare subway seat. He apologized. I gave him a hug. I slyly confiscated the knife and kept him distracted and made sure he got off on his stop — still talking with him, still hugging him, still doing everything I could to keep reaching him. And he forgot about the knife. I threw the knife in a trash can on my way home.

I have no idea what happened to this man. I certainly hope he is okay. But I knew he had a black dog like me. I knew it was my moral responsibility to help him understand that he was beautiful. Away from the knife. Away from the tough talk. Away from all the terrible pain he was in.

I have long not been a fan of Christmas because love and empathy is selectively applied. Friends have suggested that I can figure out a way to take back the holiday. So I’m doing that right now.

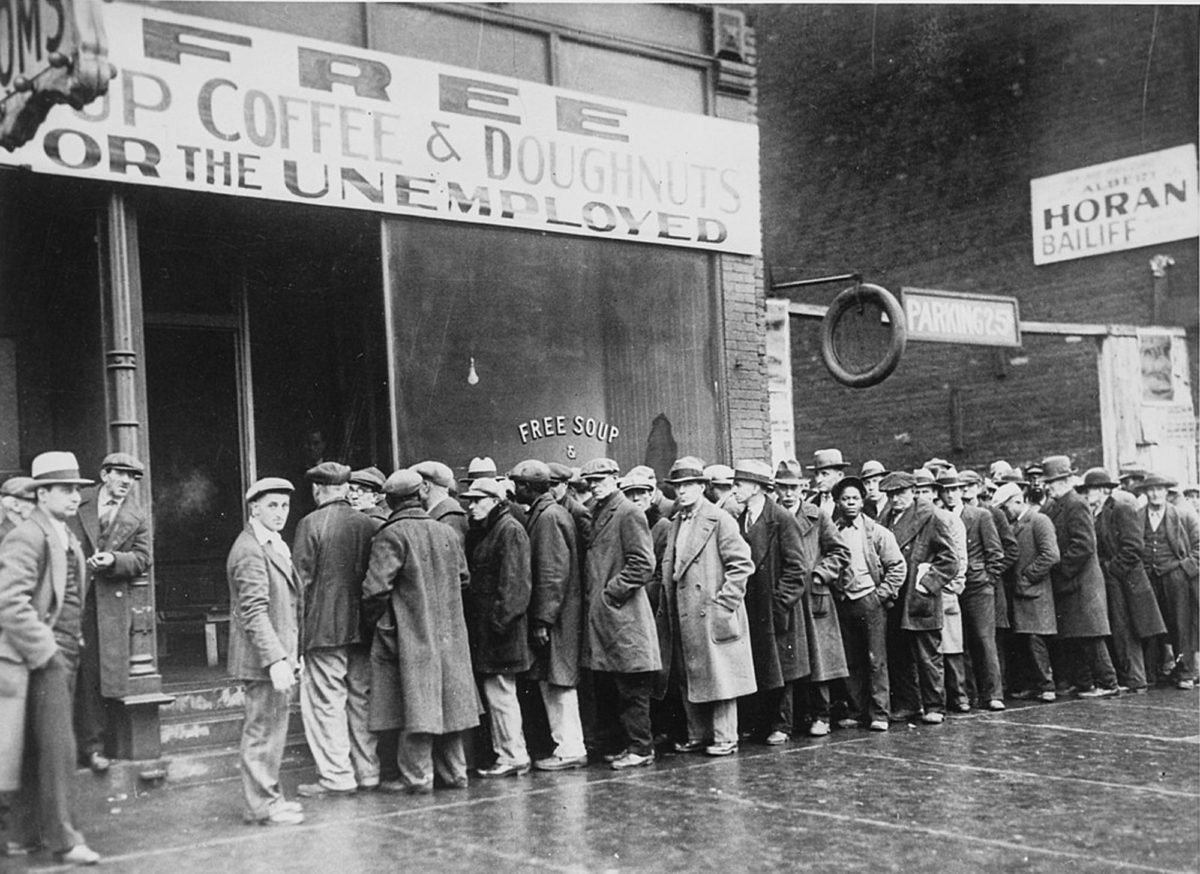

My name is Edward Champion. I write and make audio drama. Despite my flaws, I’m a pretty fun and good guy, but I also suffer from bipolar disorder. It’s bitten me in the ass a number of times. I hope that you can find it within your hearts to forgive me for my black dog, but I fully understand if you can’t. I also hope that, as you approach the holiday season, you can also understand that three million Americans — and that number merely represents the ones who have been diagnosed, not the untold number of people who are suffering right now and who may not be in the position of being able to afford treatment and who are feeling shame about their mental health — are in the same boat as I am. I hope that you can extend empathy and understanding to this considerable cluster of Americans. They are all doing the best that they can. They really don’t want to give into the black dog. But they do need your love. They do need your understanding. They do need your patience. And they need this not just during Christmas, but throughout the entire year.

For my own part, I’m going to resolve to muzzle the black dog faster. I’ve made steady progress, but I still have a long way to go. To anyone who I have ever hurt, my door is open if you need to make amends. If you don’t, that’s fine too. But if you do, please know that I will sincerely extend any and all time to listen with every ounce of earnest patience it takes and to help the two of us reckon with something that never needed to happen. This seems the least I can do.

I wish all of my readers and listeners very happy holidays.

(My considerable gratitude to Rain DeGrey, who said some very kind and necessary words to me which inspired me to own up and find the courage to write this essay. I really needed to write all this years ago. But, hey, better late than never. Peace to everyone.)